One of the first things “newbies” notice about high-end watches is the smooth seconds hand. Rather than a tick-tick movement each second, mechanical watches feature a sweeping seconds hand that appears to move in one continuous motion. This optical illusion hides an interesting aspect of watchmaking technology: Mechanical watches beat at different rates, with faster “High-Beat” movements being more accurate as well as buttery smooth.

Many novices assume that a movement that “ticks” more than once per second is a trait of high-end watches, but it’s actually nothing special. Nearly all mechanical watches, from Chinese and Japanese value lines to Haute Horology, tick at least 5 times per second! The smooth 8-beat seconds hand now associated with fancy Rolex watches isn’t the pinnacle of technology. Seiko and Zenith popularized 10-beat movements in the late 1960’s, and some exotic pieces tick even faster!

So let’s dive into the world of “High Beat” (or “Hi-Beat”) movements and see what the fuss is all about.

Tick Tick Tick Goes the Pocket Watch

Like stand-up clocks, watches use an oscillating weight to regulate their timekeeping functions. But where a clock typically relies on a swinging pendulum, watches use a balance wheel that swings back and forth inside the case. Some watches expose this wheel at the back or even through an aperture in the dial, and it is one of the charming mechanical features that draw many of us into the world of watches.

In traditional pocket watch movements from the turn of the last century, the balance wheel completed three complete oscillations per second, with each half-swing allowing the escapement to release with a “tick” as a tiny bit of energy moved the clock works. Therefore, these traditional watch movements were considered 5-beat, or 18,000 alterations per hour (A/h). 6-beat (21,600 A/h), and even 5.5-beat (19,200 A/h) movements were also common during the first half of the 20th Century.

High-Beat Chronometers

During and after the World Wars, accuracy became increasingly important. Watchmakers noticed that a smaller balance wheel that ticked more frequently would keep better time overall as well as recover their even swing more quickly after a shock, so the race was on to develop “high-beat” or “speed-beat” watches.

Most Swiss watchmakers developed 8-beat (28,800 A/h) watch movements in the late 1950’s and these came to dominate the timing competitions that were all the rage at the time. Although a 6-beat chronometer was not unheard of, the best were 8-beat or more. But this fast pace put much more stress on the gears, jewels, and lubrication inside the movement. The response was greater precision of machining and finishing as well as new materials and lubricants.

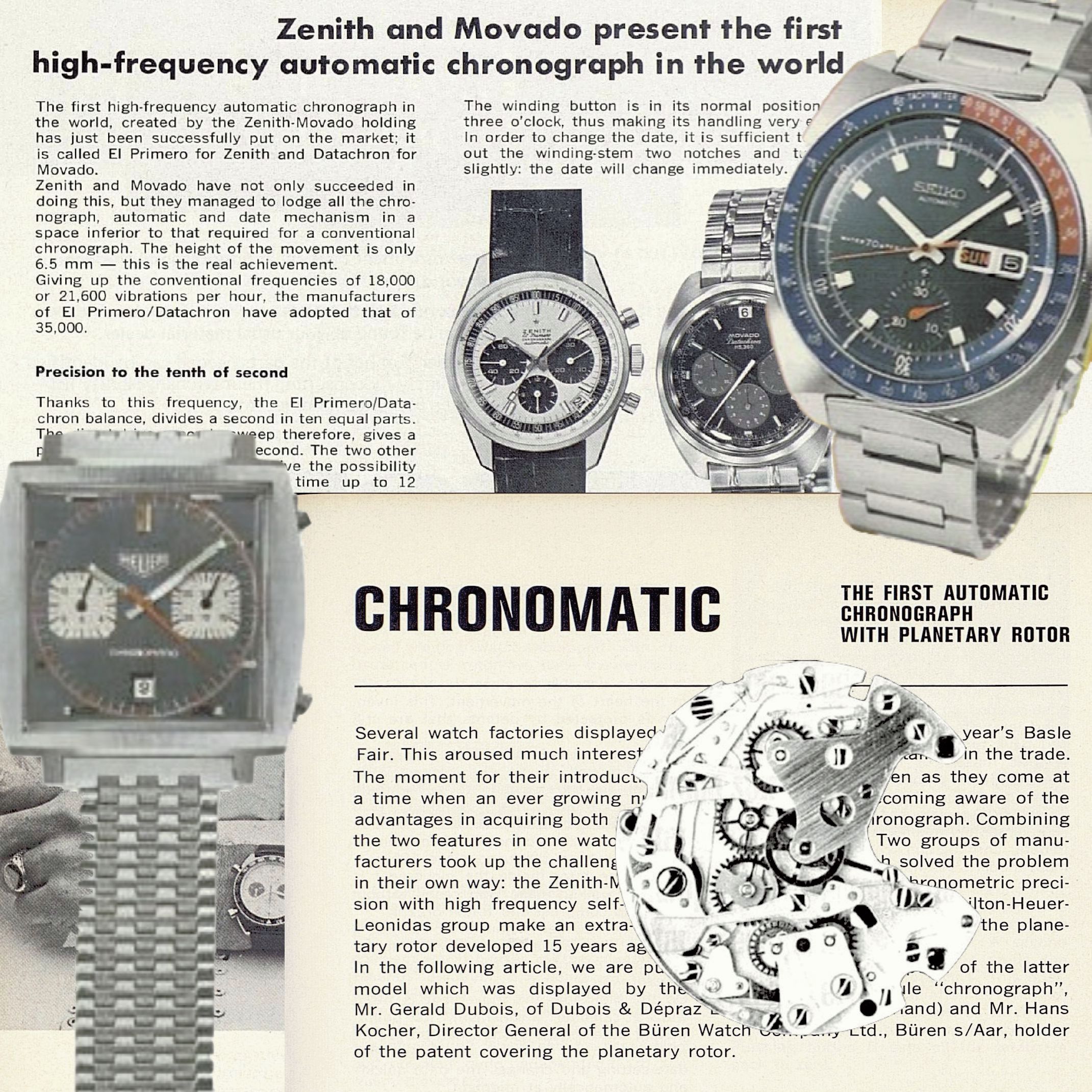

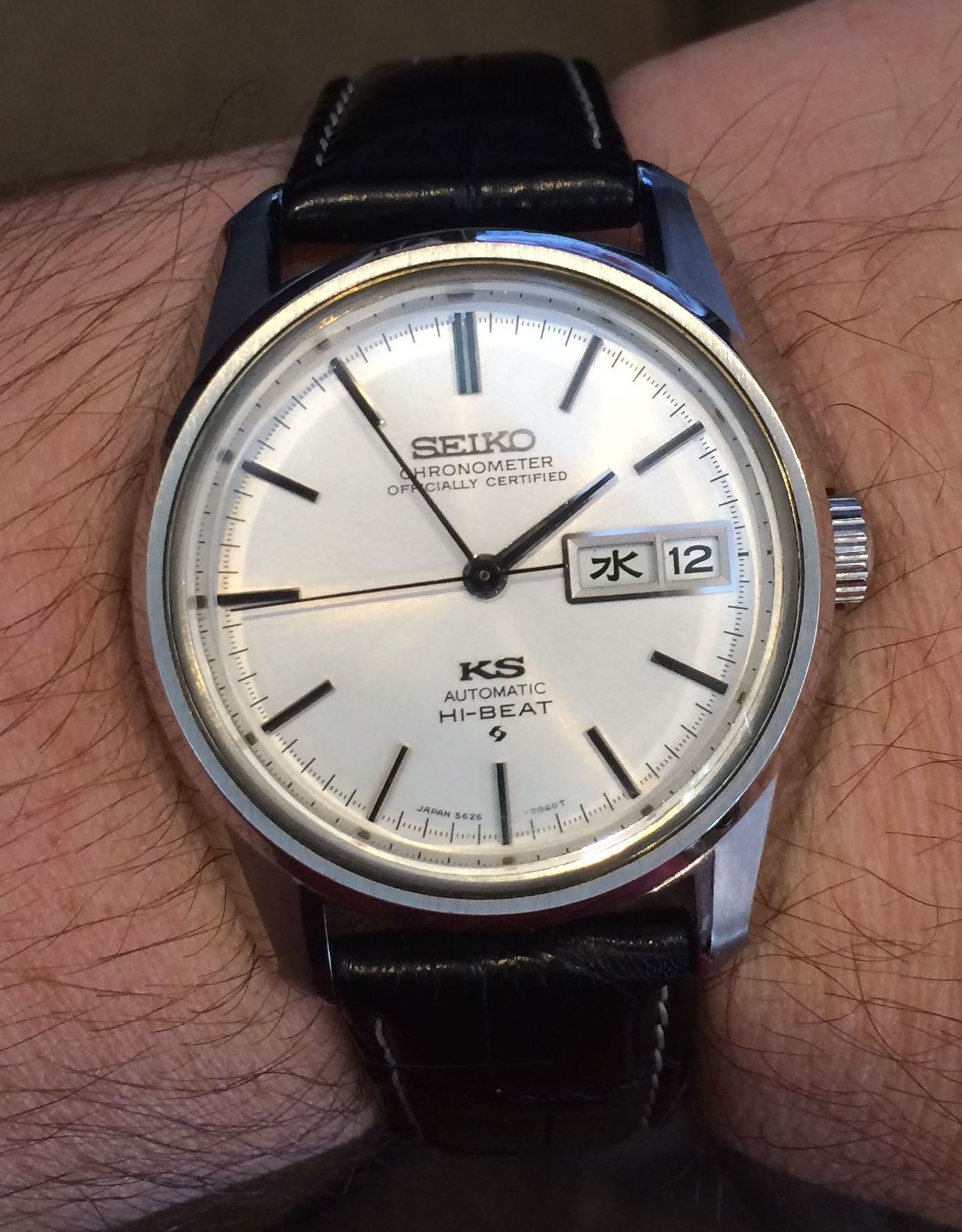

These technologies began to filter down to retail watches in the 1960’s, with most new watch movements developed as 8-beat, a sensible compromise between accuracy and durability. But Seiko, Zenith, and Buren, among others, believed that they could develop a reliable 10-beat movement and that this could give bragging rights at retail. Thus was born the now-legendary 10-beat Girard-Perregaux Gyromatic (1966), Seiko Hi-Beat 5700 (1967), 6100, and 4500 (1968) movements, and the Zenith El Primero (1969).

You might also be interested in learning the strange story of the High-Beat Buren Calibre 82

Today, Seiko and Zenith continue to be the standard-bearers for 10-beat watch movements. The El Primero continues in production as one of Zenith’s most desirable movements, and Seiko has resurrected their Hi-Beat movement for the Grand Seiko line. Modern materials and manufacturing processes mean that 10-beat movements aren’t the reliability risk they once were, but also that their accuracy advantage against 8-beat movements is no longer so great. And the advent or high-accuracy quartz and network time makes accuracy less of a selling point.

Super High Beat

Of course, a watch movement can be made to oscillate faster than 10 beats per second. Minerva’s legendary Calibre 42 from 1935 ticked at an astonishing 100 beats per second, giving this stopwatch 1/100th of a second accuracy. A few 12-beat (43,200 A/h) movements have been created, but these have not caught on in the market.

In recent years, TAG Heuer has produced an escalating series of higher-beat movements, starting with the Calibre 360 in 2005 which featured both an 8-beat timekeeping movement and a 100-beat chronograph. In 2011, they created a 1000-beat oscillator for the Mikrotimer Flying 1000, perhaps the fastest movement ever to be built. Their 2012 Mikrogirder uses electronic oscillators “ticking” 2,000 times per second.

Perhaps the ultimate high beat mechanical movement is the Seiko Spring Drive, which uses an electromagnetic clutch to eliminate the “tick” altogether. A Hi-Beat Grand Seiko may appear to glide smoothly without ticking but this is an optical illusion; the Spring Drive model actually does!

I will leave you with this video, showing 10-beat and 8-beat Seiko watches alongside a 6-beat Seiko 5 and a 1-beat quartz. After a few seconds, the video slows down by a factor of 4 so you can see the still-speedy 10-beat watch ticking alongside the nearly-stopped quartz.

If you view the video above, you’ll see that the two watches to the left, a 10-beat Lord Marvel and 8-beat King Seiko, have much smoother seconds hands.

Seiko pieces are my favorite choice when it comes to diver’s watches.Their craftsmanship is so admirable, Seiko is among the few brands that can offer a high-quality watch at an affordable price.

Great article, thanks!

I’ve been wondering; what does give the seconds hand the smooth movement? Eg. my Omega Seamaster Pro 300m was 28.000 and so is my Explorer II. Still, the sweep on the Explorer II is much more smooth. I am thinking it is not just the frequency?