Although unconventional time displays are popular today, very few watches used retrograde hands to display the time until the 1990s. So-called sector hands first appeared in pocket watches as early as 1650 and were wildly popular in the early 1900s thanks to the Sector pocket watch from Record. But it was not until the Le Phare Sectora, LIP Secteur, and Wittnauer Futurama of the 1970s that this complication appeared on the wrist. These watches are rarely seen or discussed today, but were truly groundbreaking even as the quartz revolution challenged watchmaking. Let’s take a stroll through the history of the sector watch and appreciate these rare beasts!

Retrograde Timekeeping: The Birth of the Sector or Linear Watch

Technically speaking, a sector watch shows the time using a 120º section of a circle (a “sector” in geometry). Most sector watches accomplish this using one or more retrograde hands that fly back to the start when they reach the end of the sector. Many sources claim that famed Bavarian watchmaker, Hans Buschmann created the first sector pocket watch in 1650, but I could not locate a definitive illustration of this supposed watch.

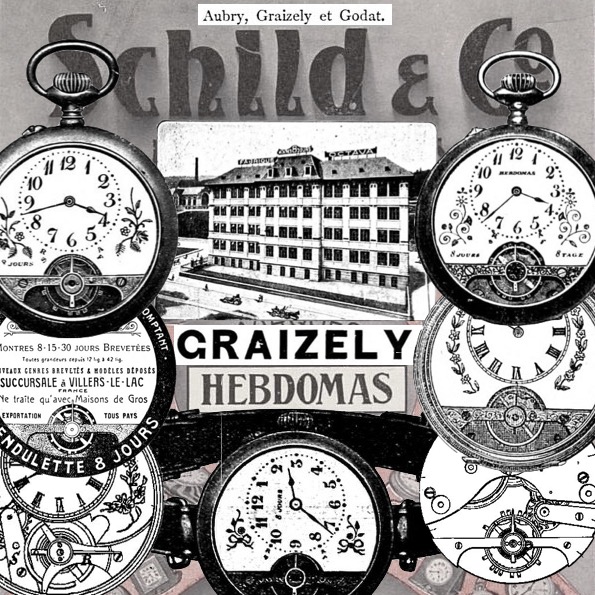

What is certain is that the Record Watch Company of Tramelan produced a series of fan-shaped pocket watches known as the Sector in the early 1900s. These were apparently quite difficult to manufacture, and modern scholars suggest that fewer than 2,000 were actually built. But the novel sector dial entered the horological lexicon and this watch has become the template for all that followed.

It’s hard to say which wristwatch was the first with a retrograde time display. Wittnauer claimed that their watch (later called “Futurama”) was the first, and often gets credit for this. But it shared a generic module with the LIP Secteur, which was displayed at the Basel Fair in 1973. It is possible that these watches were both “first” that year, but some sources claim that the Wittnauer was released in 1972, only with less fanfare.

Although this complication should properly have been called a sector dial, many contemporary sources referred to it as a linear display. Perhaps the Record Sector was not as well-remembered at the time as it is today. Clearly LIP and Le Phare used the term, but it is unclear if Wittnauer ever did.

Sector-hand watches appeared just a few years after the (mechanical) digital watch fad of 1970 and just as LED multi-segment watches were revolutionizing case design. This was a period of great creativity but also serious challenges for mechanical watches. By the mid-1970s it was generally accepted that watches would switch to quartz and electronic components and the only way for mechanical movements to survive was to innovate in other ways.

The Wittnauer used ETA’s Cal. 2784 movement, re-branded as Cal. 11 SEC in the Futurama. This was a brand new movement, with “high-beat” 28,800 A/h operation and quickset date, and was well-suited to use as a base for the Wittnauer/LIP module. Two “snail shell” cams were fitted dial-side, with a “feeler” tracing the outline until snapping back at 12 hours or 60 minutes. No seconds hand is fitted, and the date is positioned in a window to the right, adjacent to the crown. This would be the 3:00 position on a circular dial but lined up with 6:30 on this sideways “linear” dial. The Wittnauer Futurama is quite collectible today, selling for 10 times the original $150 price tag!

The LIP Secteur followed in 1973. It used the same module as the Wittnauer and thus had the same dial layout. Unlike the asymmetric Futurama, the original Secteur was more “balanced” on the wrist thanks to a large rectangular “chin” that masks some of the uniqueness of the movement. LIP used an inferior movement, the Durowe Cal. INT7525, and this caused headaches for buyers and collectors.

1970s: The Original Le Phare Sectora

It was into this environment that Le Phare introduced their original Sectora watch. The first model, shown at the Basel Fair in 1974, has a square case somewhat reminiscent of the LIP Secteur but notably different in execution.

The display is rotated 90º, with 12:00 at the top as in a conventional watch. The hour hand jumped after 6 and the minute hand jumped at the 30 minute mark, rather than at 12 and 60 as on the Wittnauer/LIP models. This gave the radical Sectora a much easier-to-read dial, with 12:00 centered at the top of the 150º dial just as it would be on a conventional 360º dial. The date window falls just below the “crown line”, roughly between the crown and fulcrum of the hands. As on the LIP, a substantial “chin” somewhat obscures the uniqueness of the retrograde hands.

The module, created by the firm of Dubois-Dépraz, was placed on a hand-winding Peseux 7046. This high-end movement with built-in date complication was also used by notables like Girard-Perregaux. It is quite slim, reducing the “boxiness” of the slab-sided Sectora despite the considerable height of the module. Note that this module uses a wide 150º arc rather than the traditional 120º of most previous sector displays. This gives it an altogether different look.

The same watch was also sold under the Marvin, Difor, and Sultana brand names. The latter is a sister brand of Le Phare, while the others were likely licensed.

Le Phare redesigned the Sectora for 1976 with what has become known as a “space helmet” case. This model dispensed with the date window entirely, though it still used the Peseux 7046 movement which includes the date function. The new design entirely obscures the dial, leaving just the tips of the hands peeking out above the “helmet”. This slim window would perhaps be more deserving of the “linear” name than any previous sector watch, but it was certainly called the Sectora by Le Phare at the time. Note that the dial, which previously showed hours above minutes, was modified with hours below, matching the level of the exposed tip of the hands.

Image: Watchtime, 5, 2001

Although the Sectora is well-remembered, this “space helmet” model is not. I am including a one-page article from Watchtime magazine in 2001, part of a special focus on retrograde watches, that presents “the sector watch” as a sort of generic product rather than as a specific model. This is not the case – the watch pictured is a Le Phare Sectora from 1976 with the printed logo worn or polished off.

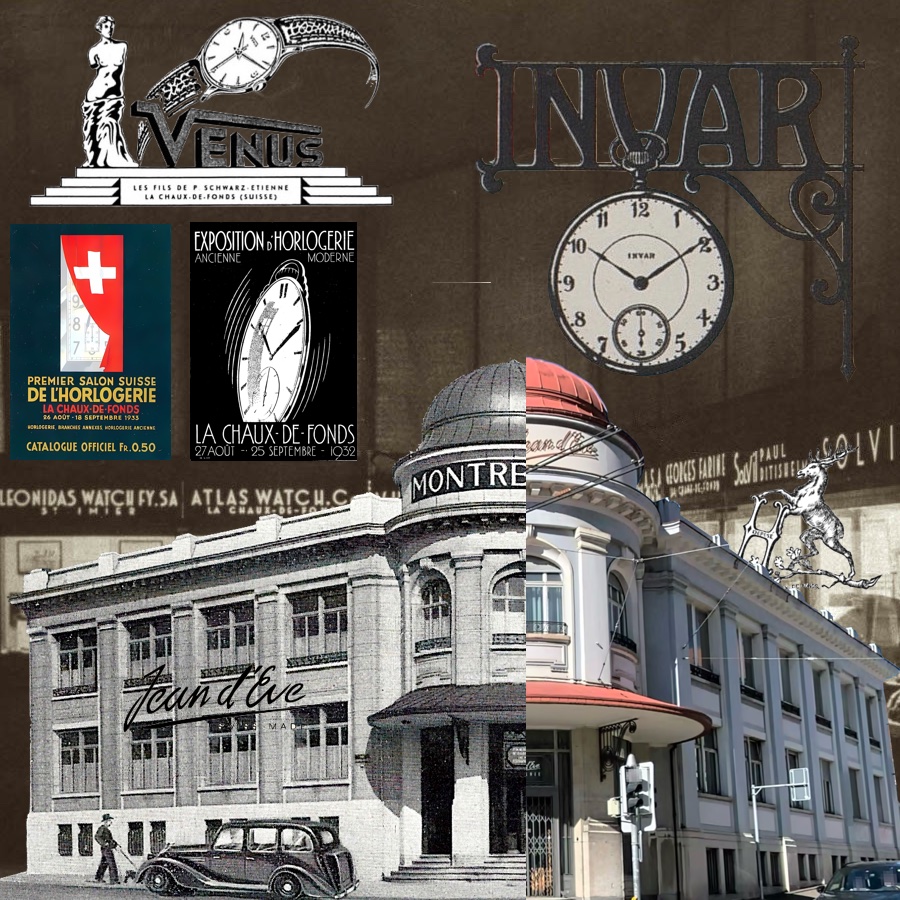

The Sectora faced an uphill climb in the market. Le Phare’s sales we suffering, and quartz watches were rapidly gaining ground. The 1970s saw an explosion of new case designs and even the radical Sectora wasn’t able to make much of a dent against the onslaught of quartz and electronic digital watches. It is unclear how long the Sectora remained in the market, but Le Phare went all-quartz just a few years later. In 1981, the Le Phare brand was retired from the market in favor of the new Jean d’Eve brand.

See Also: Jean d’Eve Samara: The First Automatic Quartz Watch

1980s: Jean d’Eve Sectora Quartz

Le Phare-Sultana SA retired the Le Phare brand in 1981 and introduced a new upscale name, Jean d’Eve (pronounced “John Dev”). This new company was pure 80s, with a lineup of stylish quartz models. They were initially successful with the Spinnaker, a sporty watch with a nautical theme and rope-textured bezel. The success of these models allowed the company to return to complicated models.

Image: Europa Star, 163, 1987

In 1984, the Jean d’Eve Sectora was reborn with a unique asymmetric seashell-shaped case. The new Sectora used a quartz movement paired with a mechanical module, perhaps the same one used by Wittnauer and LIP a decade earlier. The display was oriented with 12:00 at the top, with the retrograde hour hand returning at 12 and minute hand returning at 60. A compact ladies model was added in 1987.

This Sectora model was perhaps not as successful as the Spinnaker but it did make a mark on the watch industry. It was featured in magazines as an example of the return of complications, long absent in quartz watches. Indeed, retrograde timekeeping hands would become an hallmark of the emerging haute horology market at that time. It is important to note that may watches use retrograde calendar hands, but these move only once a day (and thus drain less power) than retrograde timekeeping hands. The same is true of the common retrograde power reserve pointers, which are usually geared directly to the barrel.

Gerald Genta, Daniel Roth, Roger Dubuis, and Franck Muller would establish their bona fides as master watchmakers based on their retrograde models in the early 1990s, and retrograde timekeeping was a critical part of F. P. Journe’s first model. In 1996, Jaeger-LeCoultre introduced the radical Reverso Chronographe Retrograde as part of their exclusive Reverso Complications series, and returned to the complication in 1999 for the more mainstream Gran’Sport Chronograph. Chronoswiss used the complication for their limited (and expensive) Delphis Retrograde in 1998, and the resurrected Jaquet Droz also introduced a retrograde watch that year. Retrograde hands were widespread in the 2000s, with Maurice Lacroix, Franck Muller, Harry Winston, Daniel JeanRichard, and others.

1993: Jean d’Eve Quarta

Image: Europa Star, 163, 1987

Jean d’Eve also showed an unusual 5-movement quartz watch in 1987. The Airport Line featured an octagonal case with independent movements for four different timezones in each corner, plus a fifth movement for the main timezone in the center. There is a whole genre of multi-movement watches just waiting to explore, but the interesting thing about this design was that it paved the way for the successor to the Sectora.

All previous sector watches used a single hand and scale for each timekeeping function, whether a 120º or 150º scale. The next complicated model from Jean d’Eve would radically change this approach, using four separate hands to represent 3-hour segments. The hand at the top right of the case shows hours 12-3, the lower right shows 3-6, then 6-9, and finally 9-12. Each hand runs counter-clockwise so the pointer roughly corresponds to the location on a conventional circular dial. Only one hand is active at a time.

Like the new Sectora, the Jean d’Eve Quarta used a mechanical complication on a quartz movement. The case was a rounded square with stepped edges, giving it a contemporary look in the 1990s. It was introduced to some fanfare at the Basel Fair in 1993. Note that some sources, including Watchtime and even Jean d’Eve themselves, have misspelled this model as “Quatra” but it seems that “Quarta” is the correct name.

This unusual manner of time display is difficult to read. The watches above at left, for example, are showing 6:49 while the one above at right is showing 7:22. It is interesting to note that the top watch is lacking the minute hand entirely. It is unclear whether this model was ever offered for sale. The numerals 3, 6, 9, and 12 in the lower watch are also unusual, since those are not “correct” for the central hand. These are removed in the 2001 photo above right.

Although this was no doubt a clever complication, it was not a particularly useful one. Jean d’Eve also offered the revolutionary Samara automatic quartz at this time, but it was clear that the company was not able to innovate and keep pace with the Swiss standards-bearers. Most of the major brands were introducing tourbillons while Jean d’Eve was just getting back into automatic movements.

1996: Jean d’Eve Sectora Automatic

By the mid-1990s, it was evident to all that the future of horology (or at least the profits) lay in mechanical movements. For 1996, Jean d’Eve introduced their first-ever automatic mechanical Sectora watch. The aptly-named Sectora Automatic used ETA’s Cal. 2892-2 and the same 120º sector display found on the Wittnauer and LIP watches 20 years earlier. Although the 2892 is a slim movement, the module adds to the bulk of the watch: It is 37 mm across and 9.2 mm thick.

Note that the top of the dial is 6:30 rather than 12:00 as on previous Sectora models. No future Sectora watch would have a 6-to-6 dial as the 1970s models had. And this would be the last “left-right” sector dial watch from the company as well.

The prodigious “chin” of this module is disguised by the decorative “flower petal” covering the base of the hands as well as an extra-thick end link. The photo above also shows the impact of a dial-side modular complication: The date wheel is set far behind the dial and the main plate of the movement is visible through the aperture. No doubt this was disappointing to buyers.

Over the years, many variations on the Sectora Automatic would appear. Most models had a stainless steel case, though Jean d’Eve offered gold and rhodium plating on some. Both silver and white dials were available. The top of the line featured a solid 18 karat gold case in yellow, white, or rose gold. These had silver dials.

Later Jean d’Eve Sectora Models

The Sectora line continued until 2016 but was no longer the sensation it had once been. Le Phare-Sultana SA had been acquired in 1991 by Hong Kong businessman, Stanley Lau’s Renley Watch Manufacturing. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Renley had been a successful contract manufacturer for Swiss and French brands, both in Hong Kong and La Chaux-de-Fonds, but this business must have waned. By the 2002, Renley was part of Free Town Watch Products of Hong Kong and the Swiss activities slowed. Although still “Swiss Made”, Jean d’Eve, Sultana, and other related brands were declining.

Available in two sizes, the Sectora 2000 returned to the look of the 1980s model, though the case is new. A quartz model launched in 1999 alongside a wave of mechanical watches, the Sectora 2000 does not appear to have been too successful. The mens version, with a 31.7 mm by 39.5 mm case, had a plain printed dial ill-suited for the ornate case. The ladies model was smaller, measuring 26.5 mm by 33.5 mm and featuring mother of pearl, diamonds, and other decorations. A rose gold dial was also available, giving a two-tone look.

A Sectana model was also added at this time, with a case much more similar to the 1980s, including the unusual lugs. This would last only a few years before being replaced by the Sectana Nuova below. It used a quartz movement and was aimed at ladies.

The most modern-looking Sectora since the original was launched at BaselWorld in 2005. The new ladies model is called Sectana Nuova, but this is mistaken for “Sectora Nuova” in various Jean d’Eve materials and third-party coverage. It is a smaller watch, measuring 25 mm across and 40 mm lug-to-lug and has a compact Swiss quartz movement inside. The sector module is more compact, allowing a truncated case without the chin or “flower petal” of previous models. It was available with either a black/Roman dial or a white mother of pearl dial.

The final Jean d’Eve Sectora was the Sectora II Automatic. Launched in 2006, it brings the automatic movement to the asymmetrical case design. Now based on the ETA 2892A2, it uses the same module seen on the other recent Sectora models with a date aperture by the crown. The 120º dial places 12:00 at the top. The case measures 37.5 mm across and is 46 mm from lug to lug. The Sectora II Automatic was produced with either silver guilloche or dark grey dials and in steel or DLC cases.

The original Quarta was an odd bird, combining difficult time-telling with a quartz movement just as the industry was evolving. It is surprising that it took 15 years for the company to launch an automatic version of the Quarta but it wasn’t until 2008 that this appeared. The new model had a modern, slab-sided case and an ETA 2892A2 movement but still retained the challenging time display module of the quartz version.

The final product of the venerable company would come in 2010: A tourbillon. But that is another story for another day!

The Grail Watch Perspective: Sector Dials

Sector dial watches represent an important development in the field of horology: Along with mechanical digital watches, they suggested an alternative to the conventional circular display, and a path forward for mechanical horology. The fact that retrograde hands became one of the signatures of haute horology in the 1990s just proves how important these sector watches were. But these were not high-end pieces, and LIP, Wittnauer, Le Phare, and Jean d’Eve are not well-known companies today, if they’re even still in business. The industry took these advances and moved on, and they did not have the resources to keep up.

Update April 17, 2020: Added more photos from the Archive.org archives of the Jean d’Eve website, including the short-lived Sectana model.

Quindi non esistono più orologi retrogradi?