This is the story of a simple postcard that compelled me along a deep and complicated path of research and discovery! Titled Les Grandes Fabriques d’Horlogerie de St Imier, the historic 1900 postcard shows “the five great watchmaking factories” of this small town. Over the past year, I’ve been learning more about these companies, in which the Jeanneret family was intimately involved, including Excelsior Park, Francillon’s Longines, Fritz Moeri’s Moeris, Droz & Cie and Ernest Degoumois’s Montres Berna, Ferdinand Bourquin’s Leonidas, and more. This is the first in a series of posts on the great factories found in these engravings!

The Story of a Postcard

This simple postcard shows five engravings of factories in Saint-Imier and is dated July 1900. “Tir cantonal bernois du 22 au 29 Juillet 1900” refers to a regional marksmanship competition held in Saint-Imier that week, so one can presume that this was a promotional postcard produced for this event. We can also presume that the postcard was created within a year of this date, and that it included five factories that would have been familiar to a general resident of the town.

1900 was an important year for Saint-Imier. The little town, about half way between La Chaux-de-Fonds and Bienne/Biel, had grown its population tenfold over the previous half-century. By 1900, over half the population of Saint-Imier was employed in the watch factories, and workers were moving there from all over Switzerland. It was a hothouse for innovative manufacturing techniques (note the billowing smoke of the steam-powered factories) and was in the midst of great conflict between labor (both socialist and anarchist) and the company bosses. The decision to place these five factories on an unrelated commemorative postcard should not be overlooked, since they were not well-documented or photographed at the time.

The five factories represented would certainly have represented the largest employers and supporters of the town. They would also have been familiar to those receiving the postcard, as named watchmakers rather than component suppliers. Indeed, some other “grandes fabriques” are missing, including the Gygax watch case and Schweingruber spring factories. It also captures a moment in time just before more great factories emerged, notably Fritz Moeri’s landmark building and Leonidas’ Beau-Site, and before those featured here were expanded so much as to be unrecognizable.

Three of the factories on the card are still standing in Saint-Imier today: Ernest Francillon’s Longines factory is immediately recognizable at the lower left (7:00) position on the card, though it has expanded dramatically since then. The Rue des Marronniers 20 factory of Droz & Cie at top left (10:00) was also recognizable thanks to period advertisements that featured similar engravings. Usine du Parc at top right (2:00) was much harder to identify, but the angled plot along the railroad was fairly easy to spot on period maps.

The other two factories (top center and 9:00) were much harder to identify, since both were quickly expanded and no longer stand in Saint-Imier. But a careful examination of period maps and photographs was eventually rewarded. The building at top center (12:00) is plainly visible in multiple photographs at Rue des Roses 2, home of a major watchmaker at the time, Ernest Degoumois. The factory at center left (9:00) was much harder to spot, but it helped knowing that Usine Centrale at Rue de l’Hôpital 6 would have been conspicuous in its absence if it was not included in 1900.

Conspicuously missing was a relic of the past: The etablisseur cottage home of the Jeanneret family, which would seed the growth of watchmaking throughout the 20th century with the sons and grandsons responsible for Excelsior Park, Moeris, Leonidas, and more. Although long-established by 1900 and extremely well known for their complicated chronographs, the Jeanneret home and workshop would not have been featured in grand engravings. Rue du Tramelan 18 was simply a home of watchmaking, not a grand factory.

Les Grandes Fabriques d’Horlogerie de Saint-Imier

This is part of a series of posts about Les Grandes Fabriques d’Horlogerie de St Imier. Due to the detailed and complicated research required, it will likely take months to complete, so please subscribe to the Grail Watch newsletter to be kept up to date!

- Introducing the great watchmaking factories of Saint-Imier

- The Evolution of Watchmaking Architecture: Rue des Roses 2 and Rue du Stand 35

- Excelsior Park: Usine du Parc

- The Rise of Mass-Produced Watches at Les Longines, Saint-Imier

- From Atelier to Factory: Usine Centrale, Saint-Imier

- Droz and Degoumois: Berna Watch Factory

- Rue de la Clef 44: Fritz Moeri’s Moeris

- The Rise and Fall of Leonidas and the Beau-Site Factory

- Gygax & Meyer

- Schweingruber

- Smaller Factories of Saint-Imier

Each of these factories has a story to tell, both about the products produced there and the watchmaking industry at the turn of the 20th century. We will explore the transition from home to factory, the rapid rise of corporations, the transition from water and steam to electric power, the great Jeanneret family, and more!

12:00 – Rue des Roses 2: Degoumois, Nivarox, and Fluckiger

Read the complete story of this factory in my companion article, The Evolution of Watchmaking Architecture: Rue des Roses 2 and Rue du Stand 35

Around 1900, a small watch factory was built at Rue des Roses 2, just northwest of the Place du Marché in downtown Saint-Imier. It was home to watchmakers Ernest Degoumois and Walter Gebel that year, but the factory would soon be expanded to cover the entire block!

A mansion around the corner at Rue du Stand 35 with a tall Beaux-Arts facade was soon integrated and would become the main address for the factory complex. As the watchmakers occupied the mansion, the factory on Rue des Roses was extended along the rear of the parcel to become home to the famous Fluckiger watch dial maker. It was also home to Reinhard Straumann’s Nivarox spring company for a decade from its founding in 1935. Eventually the entire block would be occupied by Fluckiger, making it one of the most important factories in Saint-Imier.

The complex, now known as Rue Pierre-Jolissaint 35, remains a center for watchmaking. In January 1990, the complex was taken over by Cartier Group, which was expanding at that time with the purchase of Baume & Mercier and Piaget. After being purchased by Patek Philippe in 2004, Fluckiger relocated all remaining operations to a newer building west of Saint-Imier and the site was leased to other companies. It is currently the home of sapphire glass maker Econorm, watchmaker Zeitwinkel, and a building used by trade school CEFF. If Saint-Imier experiences the same revival of watchmaking seen in La Chaux-de-Fonds in recent years, it is likely that this factory will rise again!

Image: Jura bernois Tourisme

Image: RealAdvisor

Image: RealAdvisor

2:00 – Usine du Parc: Jeanneret Frères’ Excelsior Park

Read the complete story of this factory in my companion article, Excelsior Park: Usine du Parc

I identified this cluster of buildings as Usine du Parc on Rue du Pont, home of Jeanneret Frères. A famed maker of chronographs, stopwatches, and repeaters, the company traces its history to watchmaker Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret in 1866. The Jeanneret family was involved in many watchmaking operations in Saint-Imier, but Excelsior Park (named for the factory) is certainly their most well-known contribution to horology.

In 1889, after the death of Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret, his three sons were determined to abandon home production and exploit steam power and mass production. They moved across town to this complex of buildings and immediately began to refer to it as Usine du Parc in advertisements. Watch production “a vapeur” at an industrial scale was an important step, and the engraving of this factory leaves no doubt about its purpose. But the complex of buildings is much older than Jeanneret’s use, and is present on an 1879 map of Saint-Imier. Given the large number of case and dial makers on Rue du Pont from the 1860s, we can presume that “Usine du Parc” dates from that era. Indeed, there are many claims that the complex was purchased by Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret himself in 1885 along with his brother-in-law, watchmaker Fritz Thalmann, setting the Jeanneret family to follow Ernest Francillon’s lead with mass production at the Longines factory.

As noted in the obituary of Henri Jeanneret-Brehm, this whole area of town was commonly called “Le Parc”. It was likely named for the view seen from this hill, which overlooks the valley of “les planches et les longines” and the wilderness between the Chasseral and the ruins of the Erguel Castle beyond. The steep slope below the factory walls leads down to the sawmill “Sur le Pont”, power plant, and Longines factory along the river Suze. It is said that the Gallet family suggested adopting the “Excelsior” brand along with the Anglicized “Park” as the name for the great chronograph maker set up here by the Jeanneret family, Excelsior Park.

The eldest brother, Albert Jeanneret, initially drove the business at Usine du Park, but he was already looking to create a new partnership with his own brother-in-law, Fritz Moeri. Henri Jeanneret-Brehm was next in line, and his family would lead Excelsior Park through 1984. The third brother, Constant Jeanneret-Droz, would focus more on another factory and brand, Leonidas at Beau-Site. After Albert’s death, Fritz Moeri built a much larger factory across the street from Usine du Parc, and this landmark building literally overshadowed it.

In 1911, a decade after Henri Jeanneret-Brehm took charge of the former partnership, Excelsior Park acquired the firm of Magnenat-LeCoultre in Le Sentier to expand production of repeater and chronograph watches there. But Excelsior Park remained rooted in Saint-Imier and continued to use the “park factory” throughout the 20th century. The company was lead by four generations of the Jeanneret family until it failed and was closed in 1984.

Image: CEFF

7:00 – Usine des Longines: Francillon & Co.

Read the complete story of this factory in my companion article, The Rise of Mass-Produced Watches at Les Longines, Saint-Imier

The Longines factory is perhaps the most recognizable in Saint-Imier, and one of the most famous Swiss watch factories of all. Even in 1900 the factory was one of the largest in Switzerland, and the company has remained in the building for well over a century.

At the time of our postcard, the building was called “Usine des Longines” but the company was still called Ernest Francillon & Co. The Longines brand name, which means “long meadow”, was inspired by the location of the factory in the Saint-Imier valley along the Suze river. Longines was also one of the first watch brands to be registered, and the hourglass logo is considered today to be the longest-lived brand mark in the world!

The present Longines company traces its roots to Auguste Agassiz, who came to Saint-Imier in 1832 and started his own watchmaking company. The company was taken over by his nephew Ernest Francillon in 1861, who made the controversial decision to embrace centralized production in large factories rather than dispersed home workshops. With help from his cousin Jacques David, Francillon established his first factory at “les longines” in 1867, leveraging water power from the Suze. After two decades of trouble, Francillon’s company began to grow in the 1880s, frequently adding wings and floors to the factory. By 1900, Longines had switched to steam power and dwarfed every other firm in the town.

Longines would expand the already-massive factory further in the first half of the 20th century, adding a large administrative building in front and expanding the wings on both sides. These were expanded further in the 1940s, with the facility reaching its current size by 1949. Today, Longines is one of the largest watch producers in the world and is a cornerstone of the dominant Swatch Group.

9:00 – Usine Centrale: Moeri & Jeanneret

Read the complete story of this factory in my companion article, From Atelier to Factory: Usine Centrale, Saint-Imier

This distinctive T-shaped factory with half-timber upper floors proved extremely difficult to conclusively identify. Given that the right-hand wing includes close and tall windows, this section of the building must have been constructed specifically as a watchmaking factory. But the design and size of the building suggests that it was constructed before the advent of larger industrial buildings like Usine Longines, Usine Centrale, and Droz & Cie.

Through a process of elimination, I determined that this building was most likely “Usine Centrale” at Rue de l’Hôpital 6, home of Moeri & Jeanneret from their founding in 1892. A close examination of a 1904 photo affirmed this possibility, and later photos from 1925 and 1930 confirmed this identification.

Like the Rue des Roses building, Rue de l’Hôpital 6 was quickly expanded into a factory complex, rendering it unrecognizable soon after it was built. Moeri & Jeanneret named it “Usine Centrale” as early as 1894, and continued to operate out of the building until 1949, even though Fritz Moeri established a second large factory at Rue de la Clef 44 just after our postcard was published.

A later tenant was guilloche specialist Holy Frères, who included an engraving of the factory in a 1918 ad. It was later used by Fabrique de Balanciers Réunies from 1936 to 1952, by which time the street was renamed Rue de la Malathe. Roger Parel and his successor Jacques Beiner were located there from 1949 through 1983.

At some point after 1950, the original factory complex was replaced by an apartment building, leaving only the 1907 extended wing and its entrance at Malathe 4. These remain today, with Rue du Malathe 4 housing a political think tank called World Wide Wisdom.

Image: RealAdvisor

Image: World Wide Wisdom

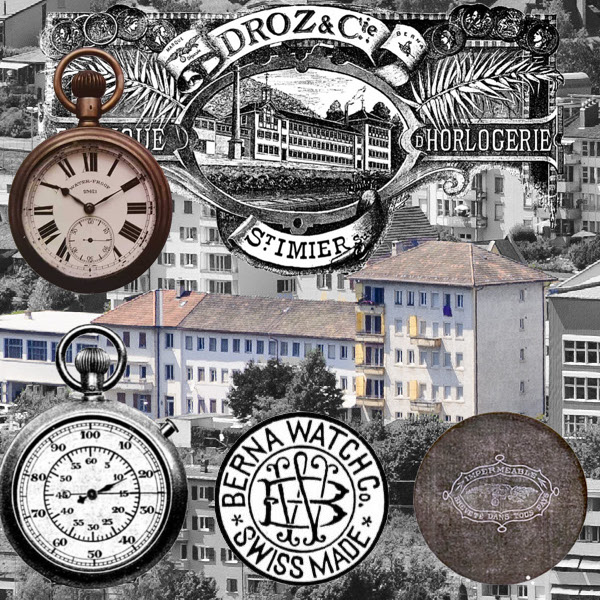

10:00 – Marronniers 20: Droz & Cie, Montres Berna

Read the complete story of this factory in my companion article, Droz and Degoumois: Berna Watch Factory

The final factory seen on our 1900 postcard is that of Droz & Cie., which produced watches under the name Montres Berna at the turn of the century. Although not well-remembered today, Droz was a major producer of watches at that time and competed with Longines and Moeris as the leading Saint-Imier factory.

The factory at Rue des Marronniers 20 had been home to the predecessor company Droz et Perret since at least 1879. It was a large building along the railroad tracks at the western edge of town and was well suited to mass production. Droz & Cie were famous for their waterproof watches, but the company experienced many difficulties. It was nearly liquidated in 1908, with the entire factory, brand, and even the Droz household offered for 750,000 francs, but does not appear to have found a buyer. Instead, Droz was reorganized by Ernest Degoumois and continued to produce his thin “High-Life” watches as well as industrial stopwatches.

Berna was joined with High Life watches in the 1920s, and this brand listed products of the old Droz factory along with those from Unitas. But the company again ran into trouble and was close to liquidation again in 1927. This time it was the Jeanneret family who purchased it, combining it with High Life and moving it to Beau-Site 8, directly next door to their Leonidas Watch Factory. Berna would continue in business through the 1970s, but the Marronniers factory was no longer used. The building still stands, next to CEFF’s main building, and is an apartment block.

Image: CEFF

More Great Factories of Saint-Imier

My search for information on “Les Cinq Grandes Fabriques d’Horlogerie” inevitably lead to other discoveries. Although overlooked by our postcard producer, the premises of Gygax & Meyer and Schweingruber were just as large as the five featured. And shortly after the turn of the century new factories were built: Fritz Moeri’s Rue de la Clef 44 was built across the street from Jeanneret Frères’ Rue du Parc; Rue des Roses was expanded to include Rue du Stand 35; Usine Centrale enveloped the former half-timber building at Rue de l’Hôpital 6; the Jeanneret family built the Leonidas factory at Beau-Site; and other smaller buildings flourished. The industrialization and expansion of the watch industry in Saint-Imier in that decade is really quite remarkable!

Rue de la Clef 44: Fritz Moeri

The large factory at Rue de la Clef 44, just across Rue du Pont from Jeanneret Frères’ Usine du Parc, is perhaps the second most notable factory building in Saint-Imier. The central tower, with wings around a courtyard, overlooks the “longines” valley, Sur le Pont, and Parc Cantonale. Moeri (later Moeris) produced inexpensive watches in volume at the location for decades, expanding the complex with another building to the west before it fell into ruin in the late 20th century.

Fritz Moeri worked for the Jeanneret family before inventing a novel anti-magnetic watch movement that could be mechanically produced in large volumes. He partnered with his brother in law Albert Jeanneret to set up a new company, Moeri & Jeanneret, to exploit this patent. After Jeanneret’s death, Fritz Moeri dramatically expanded the business, building this new factory that dominated “Le Parc”.

Fritz Moeri died in 1935 but the Moeris company continued for decades. It was merged into Rayville (along with Blancpain) in 1974 before being acquired by Tissot in 1980. The factory likely ceased operations around the time the 1974 photo below was taken.

In 2017, Usine Fritz Moeri was renovated for use by CEFF. It has been restored and updated for use by the school and is once again an architectural landmark for Saint-Imier. You can view the virtual open house of CEFF’s Santé-Social facility at Rue de la Clef 44.

Image: CEFF

Image: CEFF

Beau-Site 6 and 8: Leonidas Watch Factory

Read my complete article on The Rise and Fall of Leonidas and the Beau-Site Factory

Image: Heuer

Julien Bourquin began making watches in Saint-Imier in 1841, and his son Ferdinand continued the family business through the late 19th century. After briefly residing in the Rue des Roses 2 factory in 1901, Bourquin built a new factory on the hills above the eastern side of town in an area called Beau-Site. This would become the home of Bourquin’s Leonidas brand in 1902, and this would grow to be one of the most important watch companies in Saint-Imier after being taken over by Constant Jeanneret-Droz in 1911.

There are few photos of the Bourquin/Leonidas factory at Beau-Site 6, and this is a very unusual area with parallel and perpendicular streets all called by that name, so it was difficult identify the factory with certainty. But we can safely say that the Leonidas factory of the late 1960s is still standing.

Beau-Site 8 was the home of the Berna Watch Company (see Droz & Cie above) after it was taken over by the Jeanneret family by 1930. Eventually, Leonidas moved from the smaller Beau-Site 6 building to the larger one, and the company remained there for decades. Heuer and Leonidas merged in 1964, making this part of one of the largest watch producers in Switzerland. When Heuer-Leonidas went public in 1970, they used some of the funds to purchase the Beau-Site property, which they had rented previously. Beau-Site 8 was home to Leonidas at least until 1984, as seen in contemporary photos from Europa Star, and, despite a serious fire in 2014, remains in use by a metalworking company called Galvarex SA.

Image: Le Journal de Jura

Image: Google Street View

Rue du Vallon 26: Robert Gygax

It is curious that our postcard designer did not include the factory of Robert Gygax. After all, the large factory at Rue de Vallon 26 was highly visible, being situated near the railroad station overlooking the Longines factory. And it was an indispensable part of the Saint-Imier watchmaking establishment, turning out steel, silver, and gold cases for every manufacturer. But perhaps the large factory was not seen as equal to those of the famous watchmakers due to the fact that its products wore their brands instead of the Gygax name.

Regardless, it is certain that the cases produced at Rue du Vallon were ubiquitous in every market. Gygax was prolific, turning out cases of every description and rapidly adapting to new trends, from pendants and purse watches to wristwatches of every description. It is likely that Gygax handled the design and development of many of these cases as well, offering the latest concepts to any watchmaker in town. And the company was an early adopter of gold plating technology, bringing this to the masses before the turn of the century.

Gygax remained in operation through the 1960s. Today, the old factory still stands by the railroad tracks and is used as an apartment building.

Image: Mémoires d’Ici, Collection Musée de Saint-Imier

Image: Google Street View

Rue du Stand 18: Schweingruber

Charles Schweingruber was a maker of mainsprings in Saint-Imier at least as far back as 1869. His original address on Rue du Stand shows that the factory never moved, even as the town changed around him.

Schweingruber expanded his factory behind his building and down the hill towards Rue des Marronniers and the Droz & Cie. factory. A new road Passage de l’Industrie, was constructed around 1895 on the opposite side of the building, and this became his new address. The buildings shown in the 1898 engraving at left are viewed from Marronniers and look up this steep hill. Industrie passes between the building in the foreground and the taller one at the back.

The company passed to Jules Schweingruber in 1899. Emile Schweingruber, likely his brother, opened a factory on Rue Neuve 9 to produce balance springs soon after under the Sonia brand. By 1916 the two Schweingruber factories were competing with each other in the mainspring market, and Emile relocated across the street from his brother by 1923. By 1927, Jules was using the Lamina brand but this competition could not last.

By 1936, Les Fils de Emile Schweingruber was the only firm remaining. This firm producing Nivaflex and Ferrotex springs as part of an industry consortium by 1953 but remained in business at Rue Baptiste-Savoye 48 through the 1960s. Passage de l’Industrie is not even an alley today, and Rue du Stand was renamed Rue Pierre-Jolissaint as noted above, but the Schweingruber building remains. As expected, it’s an apartment building today.

Image: Google Street View

Rue du Tramelan 18: Samuel Jeanneret

Image: Google Street View

The Jeanneret family is deeply involved in many Saint-Imier watch makers, so it will not come as a surprise that there was another Jeanneret firm active at the turn of the century. When Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret died, his widow Cecile (née Sandoz) continued the family business on Rue du Tramelan east of town. Even as his sons branched out to build Excelsior Park (Henri, Albert, and Constant), Moeri & Jeanneret (Albert), and Leonidas (Constant), Samuel Jeanneret (the son of his brother Ulysse) maintained the family firm at home.

Samuel acquired the patent of Alfred Lugrin (who is also responsible for the Lemania company) to produce an improved chronograph mechanism. This enabled the company, later named Samuel Jeanneret, to remain an active producer of complicated chronograph watches. But the home workshop model was rapidly eclipsed by the factories used by the Jeanneret brothers, and Samuel’s firm fell by the wayside. It remained active until his death in 1939 but this true successor to Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret’s legacy was quietly deleted from the register in 1940.

Because it was a home business, there are few photos of the Jeanneret workshop. The address of the Jeanneret home changed many times between 1869 and 1939, but a careful study of maps and directories lead me to a surprising conclusion: It is likely that it was the street names and numbers that changed, not the location, and the original home of Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret appears still to be standing today! This modest house was likely the source of Saint-Imier’s reputation as a chronograph producer, and the children that grew up there are responsible for Excelsior Park, Leonidas, and Moeris!

The Grail Watch Perspective: The Power of the Factory

The concept of a watchmaking factory emerged in America in the 19th century and was brought to Saint-Imier in Jacques David’s famous 1877 warning to watchmakers there. The sons of traditional watchmakers like Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret rapidly industrialized the town around the turn of the century, and this is reflected in the remarkable postcard discussed here. The imagery of these engravings captured my attention and set me on this year-long course of studying watchmaking in the town. But a smoke-belching factory would soon lose its draw, with watch advertising turning to glamour in the 1920s and 1930s and science and sport in the 1950s and 1960s. In this way, the nature of watchmaking in Saint-Imier in 1900 is uniquely captured in this quaint postcard!

As mentioned, I will be publishing in-depth looks at each factory mentioned here in a series on watchmaking in Saint-Imier. It is perhaps unusual to focus so much on the buildings rather than the people and the products but there is much to be learned and explored there as well. In these detailed articles I will attempt to connect all aspects of watchmaking to these key locations.

References

As always, I am reliant on and indebted to certain primary sources of information about watchmaking. In particular, I relied on the archives of Indicateur Davoine, La Fédération Horlogère, and l’Impartial, all offered by RERO, as well as vintage maps, postcards, and photographs collected from many sources. The aerial photography of Saint-Imier archived by Wikimedia was invaluable, and I was thrilled to learn about the exploits of Walter Mittelholzer.

I am also indebted to Patrick Linder, who published a wonderful reference about this period of Saint-Imier’s history, De l’atelier à l’usine : l’horlogerie à Saint-Imier (1865-1918), which also features our postcard as the cover image! I purchased the book from Watchprint and am very impressed by the detailed compilation of data he performed, as well as the context he provides.

I was thrilled to see that CEFF occupies not just the old Ecole d’Horlogerie but also parts of the Rue du Stand/Fluckiger and Fritz Moeri factories. Their tasteful restoration of the Moeri factory at Rue de la Clef 44 is especially exciting to those of us who value the history of watchmaking in Saint-Imier!

I must also point out a few non-primary sources that helped in this work:

I look forward to your piece on Droz & Cie. I just acquired a watch with one of their AS movements and information on the company is hard to come by.