As Longines grew in the open valley below Saint-Imier, another large factory was opened and expanded near the center of the town. Initially just the small villa seen in our 1900 postcard, Usine Centrale would become a large and important employer, producing Moeri & Jeanneret’s revolutionary inexpensive anti-magnetic movement. It later housed electronic timing specialist Fabrique Chasseral, balance maker Romano Sieber and spring producer W. Ruch & Cie. From the 1950s, Usine Centrale produced millions of watch cases under Roger Parel and Jacques Beiner, but it has been silent since the 1980s.

For a real heartbreak, read case maker Jacques Beiner’s 1983 letter on the state of small watchmakers at the height of the crisis, translated and reproduced in the reference material for this article.

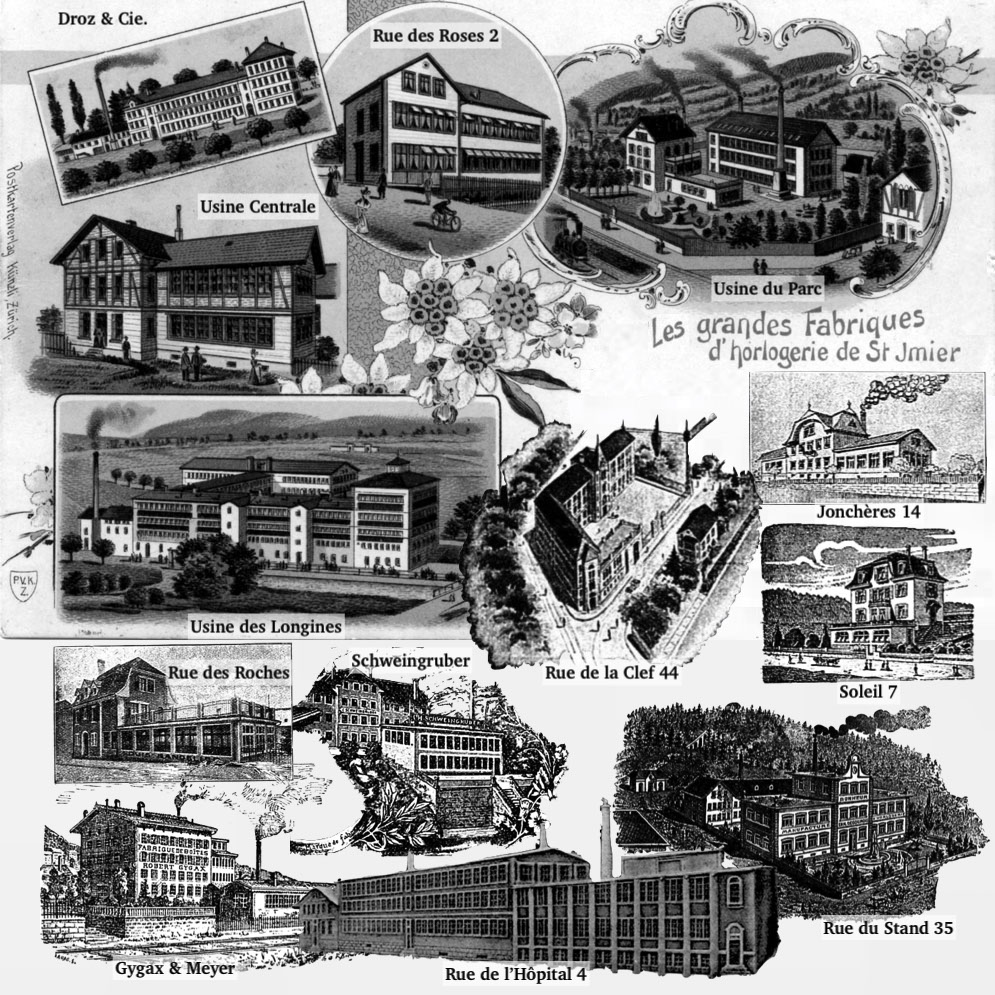

Les Grandes Fabriques d’Horlogerie de Saint-Imier

This is part of a series of posts about Les Grandes Fabriques d’Horlogerie de St Imier. Due to the detailed and complicated research required, it will likely take months to complete, so please subscribe to the Grail Watch newsletter to be kept up to date!

- Introducing the great watchmaking factories of Saint-Imier

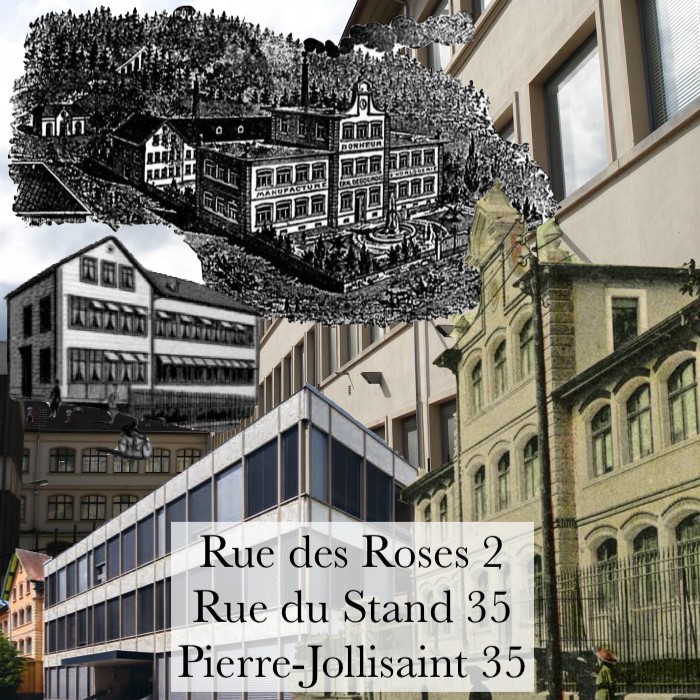

- The Evolution of Watchmaking Architecture: Rue des Roses 2 and Rue du Stand 35

- Excelsior Park: Usine du Parc

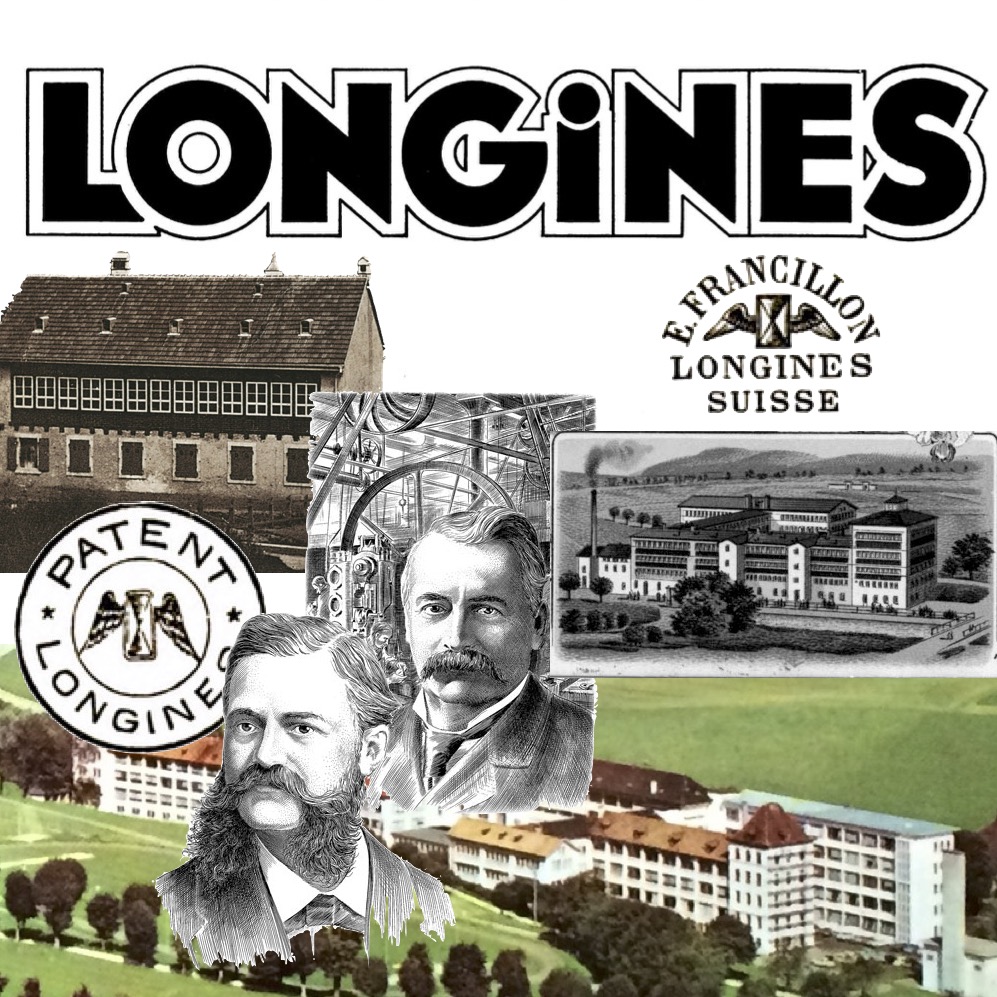

- The Rise of Mass-Produced Watches at Les Longines, Saint-Imier

- From Atelier to Factory: Usine Centrale, Saint-Imier

- Droz and Degoumois: Berna Watch Factory

- Rue de la Clef 44: Fritz Moeri’s Moeris

- The Rise and Fall of Leonidas and the Beau-Site Factory

- Gygax & Meyer

- Schweingruber

- Smaller Factories of Saint-Imier

Each of these factories has a story to tell, both about the products produced there and the watchmaking industry at the turn of the 20th century. We will explore the transition from home to factory, the rapid rise of corporations, the transition from water and steam to electric power, the great Jeanneret family, and more!

The Sons of Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret

Perhaps no family was as important to 20th century watchmaking in Saint-Imier as the Jeanneret clan. That’s really saying something considering the little town was also home to people named Francillon, Flückiger, Moeri, Bourquin, and so many more. But the Jeanneret family touched nearly every successful watchmaking business, notably Excelsior Park, Leonidas, and Moeris.

Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret (1830-1892) started his career as a finisseur of watches in the area outside La Chaux-de-Fonds known as Les Reprises in 1866 but quickly went bankrupt. Relocating to the booming watchmaking town of Saint-Imier by 1869, he partnered with Edouard Fallet, and their firm of Jeanneret et Fallet was a successful producer of watches through 1882. Jeanneret and Fallet parted ways in 1883, and the firm at 34a Rue de Tramelan was renamed Jeanneret et Fils.

Indicateur Davoine 1889

Jules-Frédéric and his wife Cécile (née Sandoz) had two daughters and six sons, three of whom would become extremely important to the watchmaking industry in Saint-Imier. Although Jeanneret’s firm continued after his death in 1892, his sons had already started their own firm. Alb. Jeanneret & Frères was managed by Henri, Albert, and Constant Jeanneret, and was established at Usine du Parc, a steam-powered factory purchased by Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret and his brother in law Fritz Thalmann in 1885.

Indicateur Davoine 1916

Despite the fact that these two firms existed at the same time (and continued for decades after), both claimed to be the successor of Jules-Frédéric’s company and dated their foundation to 1866. The situation became even more confusing once Albert left to found his own company with former Jeanneret watchmaker Fritz Moeri in 1893 and Constant left to focus on Montres Junior and then took over Leonidas. With cousin Samuel Jeanneret taking over the original family firm, there were four different “Jeanneret” companies operating in the same small town!

This explains my opening statement: Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret’s family was responsible not just for the classic complicated watches produced in his own name but also for Excelsior Park (Henri Jeanneret-Brehm), Moeris (Albert Jeanneret and Fritz Moeri), and Leonidas (Constant Jeanneret-Droz).

Moeri & Jeanneret

As mentioned above, Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret hired a brilliant watchmaker named Fritz Moeri in 1881, and he quickly rose to manage the technical direction of the company. Moeri invented an “open heart” chronograph in 1892 and was awarded patent CH4872 personally, not in the name of his employer. He was also co-inventor of CH6464/CH6465, which related to watch components and packaging, in 1893.

Fritz Moeri’s greatest contribution to horology came on November 14, 1893, when he patented his “montre perfectionnée” or “perfect watch.” Patent CH7547 quickly became known simply as “Moeri’s Patent” and was perhaps the most lucrative watch patent in the world. Moeri’s design dramatically simplified construction of the watch movement, with the distinctive serpentine opening in the 3/4 plate helping the watchmaker to align the wheels without the need for chatons or special jigs. The plate is held in place with three screws, one of which also acts to retain the crown, saving more components and effort.

Moeri chose to construct this movement from anti-magnetic materials, which required less finishing and extended the service interval. Although it was an anchor movement, the simplified construction and Moeri’s aggressive use of mechanized component construction meant it could be sold close to the cost of a cheap Roskopf or cylinder escapement watch.

Albert Jeanneret immediately saw the potential in Moeri’s patent, but his brothers must not have been so enthusiastic. In 1892, a new firm known as Moeri & Jeanneret was established, and Alb. Jeanneret & Frères at Usine du Parc became known as Jeanneret Frères under his brothers Henri and Constant. Thus, the third Jeanneret offshoot firm was born.

Usine Centrale

A new factory built just above Place Neuve in central Saint Imier became the home of Moeri & Jeanneret. It was a small T-shaped villa very similar to the Rue des Roses factory across town, with a narrow wing of tall windows specially made for watchmaking. This area was just being developed at that time, and the road was renamed and re-numbered in 1894: Rue du Malatte became Rue de l’Hôpital, making it difficult to determine if it had previously been used by another company.

This building, at Rue de l’Hôpital 6, would be advertised by Moeri as “Usine Central” (“Central Factory”) for decades, and would be rapidly extended and expanded. The explosive success of Moeri’s Patent forced the company to build a new factory south of town, directly across the street from Jeanneret-Brehm’s Usine du Parc, which will be covered in detail soon. Still, Moeri continued to be based at Usine Central until 1949.

The expanded Usine Centrale was barely able to keep up with demand for the inexpensive Moeris watches. Contemporary reports tell us that Fritz Moeri and Albert Jeanneret were aggressive in recruiting workers and pushed them to work long hours. As was common at the time, the two men were deeply involved in the outside lives of their workers as well, requiring them to attend religious services and behave in a manner they considered to be moral. A remarkable letter of complaint in the local socialist newspaper is both amusing and enlightening!

This letter tells us that Moeri and Jeanneret did not differentiate between Usine du Parc (ostensibly the Jeanneret Frères factory) and Usine Centrale, moving workers and production freely between the two. This was somewhat common around the turn of the century as demand for mass-produced watches exploded and companies like Longines and Zenith were forced to expand and take on whatever space they could find. These companies also relied heavily on outside suppliers for cases, dials, and hands, with many such factories set up in Saint-Imier and Le Locle.

Albert Jeanneret died in 1899, leaving Fritz Moeri solely in charge of the firm. He remained in charge of the company until his death in 1935, by which time the Moeris brand had become world famous. We will cover the life and accomplishments of Fritz Moeri in our article about his iconic factory at Le Parc.

Identifying Usine Centrale

Moeri & Jeanneret’s distinctive T-shaped factory with half-timber upper floors should be easy to spot in contemporary photos and maps, but it proved extremely difficult to conclusively identify. Given that the right-hand wing includes close and tall windows, it is likely that at least this section of the building was constructed specifically as a watchmaking factory. The design and size suggests that it was constructed in the 1890s, before much-larger industrial buildings like Usine Longines, Usine Centrale, and Droz & Cie. were built.

I could not initially identify this building in any of my sources, maps, or photos. So I began to work in reverse: What factories should have been included in a 1900 postcard? Indicateur Davoine used larger type to indicate larger companies, and a look at the 1899 edition shows that the most important watchmakers in town were Droz & Cie., Ernest Francillon & Co., Veuve de Jules-Fréd Jeanneret, Jeanneret Frères, and Moeri & Jeanneret. Since I had already identified most of these, the most likely occupant for the half-timber factory was Moeri & Jeanneret.

Given the growth of Fritz Moeri’s company and the importance of Moeri’s Patent, it seemed impossible that the postcard would not include Usine Centrale. In fact, if it had been printed a year later it would certainly have added an engraving of Moeri’s new landmark factory at Rue de la Clef 44. So I looked closer at all of my sources and identified perhaps the only building in Saint-Imier that matches the postcard engraving. Further examination of aerial photos of the town confirm that this was indeed the original Usine Centrale!

The Rue de l’Hôpital parcel is vacant on the 1883 Plan d’Alignement de Saint-Imier, and the first mention of a watchmaker at number 6 is the 1894 listing of Moeri & Jeanneret in Indicateur Davoine. An accompanying advertisement includes the name of the factory, Usine Centrale. The 1904 photo above shows the T-shaped building, but the 1905 Plan d’Alignement suggests that the building has been extended to the west. The 1907 Plan d’Alignement shows a much larger structure, corresponding to the large factory seen in the 1925 and 1930 photos above.

Holy Frères and Fabrique Chasseral at Usine Centrale

Guilloche specialist Holy Frères also occupied the expanded factory at Rue de l’Hôpital 6 from 1908 through 1918 before relocating their operation to Geneva by 1920. The company was founded in 1893 by François and Jules Holy of Saint-Imier, and expanded from watch case finishing to the construction of medals and prints. They are notable for including an engraving of the factory in a 1918 ad, the only contemporary image I could locate. This may have even been engraved by Holy Frères themselves!

Electronic timing specialist Fabrique Chasseral also used the factory building from 1920 through 1948. There is very little information about this company available today, but it may have been related to Longines. Francillon’s company registered “Chasseral-Longines” as a brand name in 1885, based on the name of the mountain that defines the southern wall of the Saint-Imier valley. They registered the brand “Chasseral” alone 1905, and added “Compteurs Électriques Chasseral FOSC” in 1916. Longines is said to have taken over this factory in 1922 and continued to use the name through the 1930s at least. Given Longines’ post-war activity in electronic timing, especially in the area of sports, this sounds like a fit. One could even say that this is the predecessor of today’s Swiss Timing in nearby Corgémont, which combines Longines’ and Omega’s sports timing legacy.

It seems that the original address at number 6 was retired in 1949, two years before Rue de l’Hôpital was renamed Rue du Malathe. A new entrance at number 4 was used starting in 1936 and remained the primary address for the factory through the 1970s. This door is visible in the Holy Frères advertisement at right. Although the original cottage is still visible in a 1950 aerial photo, it was torn down some time soon after and replaced by a more modern structure that still stands today. A 1970 aerial photo confirms that the building was reconstructed before this date.

Today, the building at Rue de la Malathe 6 is used as an apartment complex. Although not very visible in Google Street View, an apartment listing included a lovely view of the building that replaced the original Usine Centrale cottage and factory. The factory between 4 and 6 Malathe appears to house a political think tank called World Wide Wisdom, and their website includes a lovely photo of that section of the building. The door at Malathe 4 is now used to access the 1907 factory section, which is technically numbered 6A.

Romano Sieber, Fabrique de Balanciers Réunies

Rome-born watchmaker Romano Sieber began producing watch balances in Saint-Imier by 1920. The firm was originally located at Rue des Marronniers 22, just down the road from another balance maker, Emile Moeri-Rufer. It is possible that Sieber took over Moeri-Rufer’s business, since he is no longer listed after 1922. In 1927, Sieber moved to Rue des Fleurs 7, and he would remain there for a decade before moving to Usine Centrale.

Sieber was a founding member of the Fabrique de Balanciers Réunies (FBR) along with a half-dozen similar firms. Created by ASUAG in 1932, FBR would soon grow to include two dozen companies across Switzerland. FBR, based in Les Ponts-de-Martel near Le Locle, allowed these firms to survive as the depression threatened Swiss watch production. It controlled much of the watch balance production for decades, with most production concentrated in Martel by the 1970s. In 1984, FBR was merged with Fabriques d’Assortiments Réunies (FAR) and Fabriques de Spiraux Réunies (FSR) to become Nivarox-FAR, a subsidiary of ETA within the emerging Swatch Group.

In 1936, the firm of R. Sieber moved from Rue des Fleurs 7 to Rue de l’Hôpital 4. The company is noted simply as Fabrique de Balanciers Réunies in Indicateur Davoine through 1941 but it is undoubtedly the same firm. Although no specific address is listed in that directory from 1942 through 1962, we can assume that R. Sieber remained at the same address. It was later managed by the son of the founder, André Sieber, and Romano Sieber died in 1966.

A maker of balance springs briefly occupied the same building after World War II. Legendary materials scientist Reinhard Straumann set up a joint venture with Albert Ruch in 1934 at the Rue des Roses factory across town. After Ruch’s death, Straumann split the firm and created Nivarox SA, which remains a leading hairspring maker today. Ruch’s heirs set up a competing concern known as Spiraux Métalinox at Usine Centrale by 1951, moving to La Chaux-de-Fonds by 1953 and failing shortly after.

Casemakers Roger Parel and Jacques Beiner

Saint-Imier was known for production of watch cases long before movement production began there in the 19th century. The specialty of the town was solid gold and silver cases, but dozens of these small producers failed in the 1860s, with most gold watch case production moving to Geneva and La Chaux-de-Fonds. For the last half of the 19th century, Saint-Imier only produced steel cases, with most coming from the large Robert Gygax factory by the new railroad line.

By 1895, the Geneva firm of Georges Perrot brought production of gold watch cases back to Saint-Imier. This workshop, located at Rue des Roches 2, was taken over by Maurice Challandes of La Chaux-de-Fonds by 1913. Although the factory was soon put up for sale, there were no takers. Production of gold cases continued in Saint-Imier at a small scale through World War II.

After the war, the Saint-Imier casemaking operation of Maurice Challandes was taken over by his former apprentice turned businessman, Roger Parel. On June 21, 1945 the 50 year old firm was written off, with Parel purchasing the tooling, furniture, and supplies from Challandes for 44,000 francs in cash and a single share (out of 50) in the new firm. Challandes’ workshop had been located at Rue des Roches 2 but Parel moved it to the newer Usine Centrale building, known as Rue du Malathe 4 from 1951. Parel and his nephew Jacques Beiner built a successful business at Usine Centrale producing gold watch cases after World War II.

Parel’s health suffered, however, and the business was taken over by Jacques Beiner in 1958. Beiner also took control of the firm of E. G. Gianoli in La Chaux-de-Fonds and would build these and others into a holding company called Boitec SA in the 1970s. The company continued producing gold watch cases in Saint-Imier at Usine Centrale and in La Chaux-de-Fonds until 1983 when his firm was bankrupt, just one year after Roger Parel’s death. Jacques Beiner recognized that consolidation of the industry had eliminated the place of small independent suppliers like his company, concluding “I am weary, tired and ruined.” Read my translation of Beiner’s entire letter below.

The Grail Watch Perspective: The Evolution of Watchmaking

Like the Rue des Roses/Rue du Stand complex across town, Usine Centrale exemplifies the evolution of watchmaking, from the small ateliers that assembled components by hand to the large mechanized factories. This factory also earned a spot in watchmaking history by being the original home of Fritz Moeri’s novel mass-produced anti-magnetic movements and the birthplace of his Moeris brand. And the later tenants, supplying the industry with springs, balances, and cases, would feed the growth of watchmaking throughout the Jura Triangle. It is remarkable that one small building evolved so far as to be unrecognizable, and that it is completely forgotten today.

Reference Materials

I recommend reading Uhrenpaul’s article on the Jeanneret family to learn more about them, along with my previous article on Jeanneret Frères’ Usine du Parc.

Chronology of Tenants

- Rue de l’Hôpital 6

- Moeri & Jeanneret, as Usine Central (1894-1900)

- Fritz Moeri (1901-1918)

- Fritz Moeri SA (1920-1949)

- Holy Frères (1908-1918)

- Fabrique Chasseral (1922-1948)

- Moeri & Jeanneret, as Usine Central (1894-1900)

- Rue de l’Hôpital 4 (Rue du Malathe 4 from 1951)

- Fabrique de Balanciers Réunies (1936-1941)

- Romano Sieber, Fabrique de Balanciers Réunies (1942-1962) no address given

- W. Ruch & Cie. SA “Spiraux Métalinox” (1951-1952)

- Roger Parel SA (1949-1961)

- Jacques Beiner (1962-1983)

- Marcel Marchand (1955-1958)

- Fabrique de Balanciers Réunies (1936-1941)

Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret

Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret (1830-1892) established his watchmaking dynasty in Saint-Imier around 1868, working out of a small atelier on Rue du Tramelan 34a with his brother in law Fritz Thalmann. Each of his sons (Albert, Constant, and Henri) established their own watchmaking legacy (Moeris, Leonidas, and Excelsior Park) in the 1900s, even as his nephew (Samuel) continued his own firm.

Albert Jeanneret

Albert Jeanneret (1855-1899) was the oldest of the three well-known watchmaking brothers, the sons of Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret. Born in 1855, Albert presided over the firm, Alb. Jeanneret & Frères, from its establishment by 1889. He left this company to his brothers, forming Moeri & Jeanneret in 1893. He died in 1899, with the firm passing to Fritz Moeri.

Obituary – We write from Saint-Imier to the Swiss National:

Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie February 1899

A very large public demonstration was held to pay the last honors to one of the most appreciated citizens of Saint-Imier, Mr. Albert Jeanneret, of the watchmaking house Moeri & Jeanneret. Mr Alb. Jeanneret was esteemed not only in Saint-Imier, but in all watchmaking circles, where one could appreciate his business intelligence and above all his urbanity, his love of the humble and his concern for the interests of the worker.

But the remarkable side of this busy career is the perseverance with which, for many years, Mr. Jeanneret has spent his efforts in the service of public affairs. Municipal affairs, schools, utilitarian or philanthropic works have benefited, and benefited greatly, from the dedication of Mr. Jeanneret…

The jury responsible for assessing the various works of the overt competition in Bienne on the means of improving the watch industry, has just delivered its verdict.

No first prize was awarded, as none of the works fully met the program conditions. The following prizes were awarded to Messrs. Jules Gfeller, in Bern; Bourquin-Borel, foreman, in Bienne; Louis Muller, manufacturer, in Bienne; J. Seppibus, at La Chaux-de-Fonds; Albert Jeanneret-Thalmann, in St-Imier; Albert Guinand, in Neuchâtel; Numa Langel, in Courtelary.

In addition, degrees were granted to a series of other works.

Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie July 1886

Fritz Moeri

Fritz Moeri (1860-1935) was a brilliant watchmaker from Lyss, who began his career working for Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret before forming the firm of Moeri & Jeanneret with son Albert Jeanneret, in 1892. After Albert’s death in 1899, Moeri would build one of the most successful producers of mass-market watches in the pre-war period, Moeris, at his iconic factory at Le Parc.

Another well-known mechanical watch factory, that of Mr. Moeri and Mr. Jeanneret, in St-lmier, has also just undergone a transformation following the death of Mr. Alb. Jeanneret, reported in our August issue. His partner has taken over since January 20, for his own account and under his personal responsibility, the continuation of the business of the former house, under the name Fritz Moeri

Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie March 1900

Obituaries – Fritz Moeri, Saint-Imier

La Fédération Horlogère October 23, 1935

It was with great emotion that the population of St-lmier and the Jura region learned of the death, in Geneva, of Mr. Fritz Moeri, the venerated founder and administrator of the Moeris Watches Factory, F. Moeri. SA, in St-lmier.

Born in 1860 in Lyss, Mr. Fritz Moeri came to settle in St-Imier in 1881, to enter the services of the firm of Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret et Fils, a watchmaking counter, where he was soon to be appreciated by its leaders. The deceased founded, in 1892, in association with Mr. Albert Jeanneret, under the company name Moeri & Jeanneret, a watch factory whose new manufacturing system was based on the principles of absolute interchangeability. Fritz Moeri, always in search of new improvements, and breaking with what was being done then, again introduced methods of machining the roughing and finishing of the movement: this was the beginning of a new orientation of the movement and mechanical manufacture of the watch, which he was one of the first to design and above all to produce.

Mr. Fritz Moeri. to see his talent and his mind continually alert, was one of the innovators in the field of watchmaking and it is no exaggeration to say that he contributed immensely to the development of our industry at this moment. Moreover, his qualities of organizer and leader were able to assert themselves even more, that is to say after the death of his partner Mr. Albert Jeanneret, in 1891 [sic]: indeed, since then, he alone assumed the heavy task of continuing his industrial activity in St-lmier.

The premises then occupied were no longer sufficient and the deceased decided to build the current factory, which he continued to expand thereafter. Since 1918 it has been owned by Fritz Moeri S. A. Until recently, the deceased was very active in the factory he had created, which is his work, a magnificent wall and due to the spirit of tenacity, the will, the constant work of the one who was a great and honest head of a watchmaking company.

The deceased took a keen interest in public affairs. He was part of numerous commissions: School of watchmaking and mechanics, where his opinions were very much listened to, Société du Contrôle, where he had his rightful place, Cantonal Bank of Bern, Industrial Services, Grand Council of Bern, etc.

Fritz Moeri is one of those people whose example should be followed. St-Imier owes him a lot of his development and the unanimous population, more particularly those who knew him more closely, his staff whose collaboration he always appreciated and whose needs he also knew, will remember him best.

May his grieving family believe in our deep and sincere sympathy.

A Letter of Complaint About Moeri & Jeanneret

In October, 1894, the socialist newspaper La Sentinelle published the following letter. In it, an anonymous worker complains about his treatment at the hands of Albert Jeanneret and Fritz Moeri. He calls the former “an enormous captain-preacher” and the latter latter “little man in the guise of a saint,” and the letter gets angrier from there on. Interestingly, it shows that the Moeri factory at Le Parc and Usine Centrale were one and the same from the perspective of the workers who labored there. I present below my translation of this amusing letter!

We receive the following correspondence. Unable to control the facts it relates, we leave all the responsibility to its author.

La Sentinelle, October 25, 1896

(Private correspondence of the Sentinel) Saint-Imier.

It was told to me by a worker, who is responsible for what he puts forward, facts that deserve to be known so that, if his colleagues were tempted to go and work for Mr. Mœri and Mr. Jeanneret, Usine du Parc, in St-Imier, they know their position in the said factory.

For the clarity of the story, a small sketch of the two bosses is necessary. First, both are very religious people. M. Mœri, ex-scraper, little man in the guise of a saint, speaking softly but with such an air of disdain that he causes a worker to back away, with the hair rising on the back of their necks. M. Albert Jeanneret, an enormous captain-preacher with a more than usual figure, only poses for goodness and charity. In this factory of good people there was a young man of 22 who ate in a boarding house on a ration, and for some time he had only been seen in the evening at supper. A colleague asked him one day, “but where do you have dinner, not to mention lunch?” The young man finds himself embarrassed and ends up saying to him, “you see, I earn so little and I have my military tax to pay, that’s why I’ve only lived on suppers for two weeks!” And this with the knowledge of the bosses, for the fat preacher has told people that he and his wife hardly got to dinner one day only to find this young man remaining in the factory during the hour of rest. So, the next day, he was forbidden to stay in the workshop, but without in any way trying to improve his position! Oh, for the love of Christ, how can this be understood?

Then, a worker coming from Le Locle in search of work asked them for a place. He was received by the little saint who asked an enormous number of questions, morality above all. The worker replies, “I will do everything possible to satisfy you. I have six children and therefore I need the money.” But, that was not enough, and he was answered with a cunning air, “I don’t have much confidence in these gentlemen (who authored the worker’s certificates); I will need more information.” The next day, he deigned to tell him that he could come in the following Monday. Our man, seeing all these formalities, thought he was entering a first-rate house where it is enough to do one’s duty to be occupied for a long time. And all the more so since there were still signs at the doors that, given the volume of work, work days were being extended by an hour. Finally, at the end of three weeks, as it was too expensive, he summoned his household from Le Locle, but not without having repeatedly warned his bosses, asking them for a place for one of his children and telling them the date of his move. He let the worker’s family settle in and, once he felt he was trapped, had the audacity, in the manner of the mômiers (Puritains) to decide that to earn 50 francs a fortnight was too much. So his work was arranged so that he could only earn 38 francs a fortnight, and that without wasting a minute. Our man was chomping at the bit, without saying a word. It was raspberry season and if his children hadn’t sold some, they would have been hungry. Not satisfied with this result, one month, to the day, after his move, he was given a letter in which he was told that the firm was very happy with him but, with regret, he was given his notice. However, if after a fortnight he hasn’t found anything, he’ll be given a little more work, half the time.

Our worker also continues his work, looking everywhere, and, eight days after receiving this letter, he was questioned by the little saint to find out if he had found anything. He replied no and explained clearly to him the cowardice of their conduct, thus throwing an entire family on the pavement and showing them that this letter was intended, knowing that he would find nothing in St-Imier, only to deliver him hand and foot bound to these exploiters who would offer him a pay of … mystery! Finally, pushed to the limit, the little saint told him to address the big one, to change the game. The fat man said to him, “you can work in the new factory,” decorated by the preacher with the pompous title of Fabrique Centrale. Its real name should be “Factory of One Hundred Pennies,” marking the time of meals that one should be able to eat, otherwise known as “Factory of Cravings.”

This house was built by decent people for some industry, not to turn it into a temple of “sellers.”

Finally, back to our subject. Our man entered The Cravings (Centrale) and, for seven days, he was showered with insults and injustices by these people who could not bear to have received a lesson from a worker, and tortured by these beings who are the plague of factories, which are called snipers and swaggerers. Of those types who are neither directors nor visitors, but simply bullies. Lastly, on the sixth day, having taken a very young man to do the same part and, seeing that he would come back much cheaper than the one with six children, the latter was permanently fired the next day.

And this is how we lead to misery and hatred of workers and, that, by saints and preachers!

Jacques Beiner’s Letter

Casemaker Jacques Beiner took over the business of Roger Parel in Usine Centrale at Rue du Malathe 4 by 1962 and remained in business there through the early 1980s. By this time, the combination of the currency crisis of the 1970s and the rise of international competition from quartz watches in the 1980s hit small producers hard. As Nicolas Hayek merged ASUAG and SSIH to form the entity now known as Swatch Group, many small producers were ruined by bankruptcy. Such it was with Jacques Beiner, who penned a heartbreaking letter in the newspaper l’Impartial on May 26, 1983. I reproduced the letter above and present the English text here.

Ruined but responsible

You will read, correct or cut my text, because I am not a writer or you will not let it appear in your columns! For my part, I have read and reread this whole SSIH-ASUAG affair and the whole history has been replayed in my memory since the post-war period.

At that time, the big houses – as well those of SSIH, ASUAG and SGT – belonged to bosses, often elderly, respectful and respectable, and all their factories were marked by the same spirit, from the head of department to the concierge. I personally maintained very courteous relations with these gentlemen, often much older than myself; a supplier was a collaborator that we needed at Longines as well as at Invicta, at Lanco as at Avia, Lemania or Zodiac. All these business leaders had known the other crisis.

The years have passed – quickly. It was the era of concentrations. Large groups were built where no one knew anyone. The then chiefs were replaced with increasingly substantial salaries by directors of this or that – marketing, styling and so on – the supplier was replaced by a number on the IBM…

It was also the moment when with great noise the Minister inaugurated factories in Mexico City, Brazil, then in the Far East which were simply going to compete with us. It was beautiful, it was big, we no longer saw national but global, we even made agreements with the USSR to communicate our technology to them. The boomerang was launched, we would soon receive it on the face in return!

“Before” we had agreements and payments were strictly enforced. But with all these upheavals and bosses replaced by more and more directors, a supplier no longer had a name, let alone an identity; it was part of the subsidiary branches with all that that entails of pejorative. The “commitments” no longer existed, pending and pending orders piled up on the shelves. Sometimes a great manager with a name, everyone had at least seen their photo a few times in the newspapers, condescended to take your call: “We will take care of you.” All this great fuss continued, the directors were replaced by others even more numerous, but even less accessible, especially when we spoke of stocks of boxes in progress or completed for years! One group broke down, another closed or “sold” successively Lanco – Aetos – Economic Swiss Time satellites. The new ones no longer recognized the commands and commitments of the old ones. All this caused even major suppliers to go bankrupt. La Centrale, Graurex, etc, etc.

I am telling all this because I lived it. In 37 years, I have been able to produce in my workshops several million gold, steel, and metal watch cases, and this represents a turnover of several hundreds of millions, with what that implies of purchases, sales, subcontracting and salaries. Not to mention also the time when, because of the unconditional position of the unions, it was not possible to hire a woman, a laborer or a foreigner! This also undoubtedly encouraged the establishment of competing houses in other countries. Now, it’s a little late, we are faced with a labor force that is up to 40 times cheaper, while at home – despite the crisis and the debacle – we continue to claim and in no case to let go whatever the social gains. Follow one another on television, MM. Tschumi, Gehlfi or Prince who have sufficiently made their members understand that the boss is the enemy. We also talk about co-management: Is it so successful in a neighboring country? Where under the socialist regime we state, which amounts to the same thing to immediately go on strike (eg Régie Renault).

I am weary, tired and ruined. Even the machine on which this letter is made is already sold, for 50 or 100 francs perhaps. And in the inexorable cascade, I will also lose smaller suppliers, in reduced proportions, but with the feeling of having tried everything and yet I end my working life in failure, while those who made me crack don’t care and often don’t even know me. This is progress. Was it mismanagement to be dragged down by the losses of insolvent clients and the failure to meet their commitments? And Jean Ziegler, obsessed with the multinationals and the big banks which profit from the third world, does not see that these same big banks save 15,000 places of work knowing how to lose in our own country a billion. I wonder how these clever purposes of the big watch groups who have not invested a franc in their business have managed to borrow such sums. They have not risked anything, while the little boss is bleeding, leaving all his personal assets, his life insurance as collateral, so that his wife and children have nothing left either, then sacrifices his own pension fund to pay the employer’s share of his workers.

Jacques Beiner, industrialist

Saint-Imier

l’Impartial, May 26, 1983

Leave a Reply