The pattern of high demand, over-production, and collapse is common in all industries, but especially in the history of Swiss watchmaking. We see it repeated throughout the 20th century, from ebauches to complete watches, but all of these efforts trace their roots to a crisis focused on the humble balance spring. Surprisingly, this very first attempt to create a cartel was also the most successful and disruptive! This is the story of Société des Fabriques de Spiraux Rèunies, which cornered the market for balance springs in 1895. The FSR was the template for Ebauches SA, ASUAG, and the Swatch Group, and we would be wise to study the lessons of this “cartel crisis”!

Spiraux, Ressorts, and Secrets

Before we begin to discuss the cartel, the crisis, or even the companies involved we must understand the topic. What is a balance spring and why does it matter?

Like batteries today, springs have long been the essential commodity that made portable mechanical devices possible. There are two types of springs in every watch: The mainspring, wound in a barrel, provides raw power; while the balance spring and balance regulate timekeeping. Although similar in concept, these two springs could not be more different in construction and material!

Note: There was actually a third common type of spring in the 19th century: the “secret spring” was used in watch cases, allowing them to pop open at the press of a button!

Timekeeping in a watch is handled by three separate elements: The escapement (anchor and wheel), the spring, and the balance. Each is entirely different in material and construction, and each was produced by a separate company until the 1980s. Because of the complexity and importance of these parts, specialized producers were organized by ASUAG into three cartels in the 1930s: FAR, FSR, and FBR. But now we’re getting ahead of ourselves!

The French word for spring is “ressort”. Alone, this word commonly refers to the mainspring, though this is properly called a “ressort de barillet” or “ressort moteur”. A balance spring is properly called a “ressort spiral” but these are typically referred to as “spiraux” (plural of “spirale”). This is similar to German, where “feder” means spring and balance springs are “spiralfedern” or often simply “spirale”. We call both “springs” in English but often differentiate them as “mainsprings” or “barrel springs” as opposed to “balance springs” or “hairsprings”.

Image: La Fédération Horlogère, December 12, 1940

Though there is some controversy, Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695) is credited with the invention of the spiral spring in 1675, and these soon diverged into springs for power and springs for timing. John Arnold (1736-1799) thought of adding a sharp terminal curve to his cylindrical spiral in 1775, and Breguet (1747-1823) created the prototypical terminal curve balance spring. The creation of each type of spring requires different tools and skills, though most were made from steel in the 19th century. Unsurprisingly, different craftspeople and workshops specialized in spiraux, ressorts, and secrets. But the construction of each was more art than science until French mathematician Édouard Phillips (1821-1889) began to methodically investigate and document the optimal shape for balance springs in the 1860s.

The industrialization of watchmaking in the late 19th century also affected the construction of springs. What had once been a home handcraft could now be somewhat mechanized with steam power and specialized presses. This was especially true of barrel springs (“ressorts”), which quickly moved out of the workshop and into the factory. But balance springs still required careful and meticulous shaping, and hand regulation was required for constructed movements and watches, since the variability of balance and spring was unpredictable.

The Rise of Balance Spring Factories

In the first half of the 19th century Swiss workers cut and shaped raw steel into balance springs by hand. Interestingly, work on balance springs was typically performed by women rather than men, and this was true even in the spring factories of the 20th century! But England was far ahead of Switzerland when it came to fine spring making, and America pioneered mass production of these components.

Seeing that they were falling behind, the Société d’Emulation Patriotique de Neuchâtel offered a prize of 12 Ducats to anyone who could develop comparable skills and tools in the country. The winner was selected by none other than Jules Jürgensen (1808-1877), a famous Le Locle watchmaker like his father, Urban Jürgensen (1776-1830). The winner was Olivier Quartier-dit-Maire (1776-1852) of Le Locle, though his winning springs were actually crafted by six women employees. He previously won the same prize for his invention of a widely-used machine to finish gear teeth, and he served as a local justice. This competition helped spur new spring manufacturing in the Neuchâtel region.

Image: Indicateur Davoine 1875

As new tools were invented to produce balance springs, and the skills required to tune them became more specialized, the first mass producers began to appear. Louis-Auguste Guye produced the first factory-made springs in 1844. Called “Le Capitaine” by his employees, he soon established the first spring workshop in Geneva. Another factory was set up there by Páquet and Rivenc the following year, and a similar firm was created just across the border in Ferney, France by Siblet. Around 1850 the Perret-Gentil family in La Chaux-de-Fonds and Gérard family in Lyon, France began to produce springs as well.

Jean-Célanis Lutz of Neuchâtel was particularly important, having invented a process of quenching steel to create hardened balance springs (“trempés”). From then on, ordinary springs were known as “mous” (“soft”). Soft springs were used in both cheap (unadjusted) and expensive (hand-adjusted) watches, with hardened springs taking the middle range. His invention was recognized with an 1850 award from the Société des Arts de Genève as well as a Medal of Honor at the Universal Exhibition in London the following year.

Sometime I hope to tell the tale of this shy Swiss craftsman and the impression he made on Prince Albert and Queen Victoria!

The Battle of the Spring Makers

J.-C. Lutz died in 1864, leaving his modest workshop to his daughter Emma. The firm soon split, with Charles Dufaux building a large new factory and Adolphe Montandon-Lutz reviving production at the old workshop. Dufaux ultimately took control of the respected Lutz name, leaving Montandon-Lütz with an umlaut to differentiate his operation. Philippe Guye inherited his father’s Geneva spring-making workshop and began large-scale production in the 1870s. George Sandoz moved from La Chaux-de-Fonds to Geneva to take over the Rivenc-Páquet factory around the same time. Then there was watchmaker and amateur scientist Charles-Auguste Paillard (1840-1895), who perfected the palladium balance spring used by marine chronometer makers. Thus, five major factories were making balance springs in Geneva in the 1880s: Dufaux Lutz, Philippe Guye, Georges Sandoz, Montandon-Lütz, and C.-A. Paillard.

Image: Indicateur Davoine 1880-1882

Bienne was rapidly rising as a watchmaking city at this time, with the city fathers offering tax incentives to lure production there. Jean Baehni-Ronget and his wife started out in La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1863 but were attracted to up-and-coming Bienne, moving their factory there by 1877. The firm of Baehni et Cie would grow to supply half the balance springs in the world by 1890, which amounted to over 6 million springs per year!

Image: Indicateur Davoine 1894

Finally we turn to La Chaux-de-Fonds. Jules-Henri Huguenin-Girard (1827-1886) got into the watch business after marrying a young widow, and later took over the La Chaux-de-Fonds operation of Perret-Gentil. After his death in 1886 it passed to his own widow and son, also named Jules Huguenin-Girard (1869-1897). Although not as large an operation as Baehni in Bienne nor as varied as the Geneva firms, Huguenin-Girard had the benefit of location in the “watchmaking city” of La Chaux-de-Fonds. And the young and energetic Jules had a good head for business like his father.

The Origin of the Balance Spring Crisis

The spring makers supplied depots in each watchmaking city and town, heightening competition. The watchmakers could easily switch suppliers, so they demanded special deals and aggressively pushed the spring makers to cut costs. And the boom and bust in watchmaking left the spring makers on the brink of collapse. Even Baehni & Cie., with a roughly 50% market share, could not control the wild swings in pricing.

Things were shifting as the 1890s approached. Adolphe Montandon-Lütz died in 1883 and his widow was uninterested in competing with the other Geneva manufacturers. The firm soon gave up the old Lutz workshop and moved in with Georges Sandoz. Charles-Auguste Paillard’s health was failing and he was unable to squash competition for his expensive palladium springs. Philippe Guye attempted to bring his sons Philippe-Auguste and Charles-Eugène into the family spring business, but the brothers were brilliant scientists who were more interested in pursuing and teaching chemistry and physics.

Charles-Eugène Guye was one of Albert Einstein’s teachers and helped prove the special theory of relativity, while Philippe-Auguste Guye was nominated for the Nobel Prize five times!

Image: La Fédération Horlogère, January 28, 1892

These changes made the spring makers more amenable to the idea of some kind of coordination between the companies. In 1892, five balance spring factories (Baehni, Sandoz, Dufaux, Guye, and Montandon-Lütz) created the Syndicat des Fabricants de Spiraux to exclusively negotiate and supply members of the Syndicat des Fabriques de Montres. But both organizations proved ineffective and were undermined by side deals. Something more reliable was needed.

Finally the spring makers considered the un-thinkable: They would merge their companies and monopolize spring production as a single firm.

Société des Fabriques de Spiraux Réunies (FSR)

In 1895, the six major producers of balance springs came together with a novel idea: They would form a cartel to corner the market and control pricing. The founders pooled their money to purchase every maker of balance springs (including their own) and set up a single sales outlet. There would no longer be any competition in springs!

Rumors of this new cartel swirled in watchmaking circles, but no one was prepared for the announcement that was made in November: Effective immediately, none of the producers of balance springs would sell directly, with all orders processed through a clearinghouse in Neuchâtel. No notice or warning was given, for fear that panic buying and hoarding would ensue.

Image: La Fédération Horlogère, April 17, 1898

Unsurprisingly, Jean Félix Baehni (1863-1895) was the leader of this effort. Since it was the largest, his firm had the most to gain from production and price controls, and would be hurt the most if the effort failed. He convinced George Sandoz, Charles Dufaux, and Philippe-Auguste Guye of Geneva to join him, and Jules Huguenin of La Chaux-de-Fonds accepted as well. None of the other spring makers cared to stand in the way: Montandon-Lütz was effectively out of business, A. Goy-Blanc (specialist in anti-magnetic springs from Le Brassus) was more interested in other aspects of watchmaking, and Charles-Auguste Paillard died a few months later.

Even more shocking than the sudden emergence of the FSR was the financial impact: The price doubled, no negotiation was allowed, and no previous deals would be honored. Angry voices were raised, and a vigorous debate took over the pages of La Fédération Horlogère and other trade journals. Perhaps the most vocal voice against the cartel was Fritz Huguenin (1847-1917), editor of that important publication and future chairman of the Swiss Chamber of Watchmaking. The vigorous debate in the press is marked by his dry sarcasm and wit.

Yet the spring makers justified their move in the name of saving the industry, improving the pay of workers, and enhancing product quality. And they were insistent that the bruising competition of the previous decades threatened the entire system of watchmaking in Switzerland. This was perhaps the most important lesson from this first cartel, and was embraced by the next generation of watchmakers: Cartels and control could help reinforce the industry rather than undermine it.

The new firm was officially incorporated on December 17, 1895. Although the clearinghouse soon moved from Neuchâtel to La Chaux-de-Fonds, the general structure of Société des Fabriques de Spiraux Rèunies (known as FSR) would remain in place for decades.

Image: l’Impartial November 13, 1895

The unsung hero of the cartel was Charles-Albert Vuille (1866-1949). Recruited in 1898, Vuille rationalized production at just a few locations and helped set a sustainable pace for the workshops. Born to modest means, Vuille was emblematic of his generation of watchmaking industrialists and was involved in many different firms across the industry. Although he ran the balance factory in his home town of La Sagne he dedicated most of his career to furthering the goals of unification of production of spiral springs. In decades to come, Vuille was able to convince rebels and dissidents to join the cartel, or at least agree to production and price controls. Although he was struck ill and forced to retire in 1931 just as the industry was unifying, Charles-Albert Vuille lived long enough to see the fruits of his work.

Image: Indicateur Davoine 1896-1897

The Watchmakers Strike Back: Société Suisse des Spiraux (SSS)

Watchmakers were furious about this price increase, but also the loss of the power they once enjoyed when negotiating with component makers. They first tried to force regulators, who were typically independent at this time, to absorb the increased cost. But the FSR intentionally set the spring price too high, forcing these key suppliers to pass the costs on to watchmakers. Infuriated, these companies could do nothing but accept the new rate for balance springs from FSR.

Still, the etablisseurs did not sit idly by and accept the situation. Watchmakers from La Chaux-de-Fonds and Geneva met in the spring of 1896 to formulate a response. Their solution, boldly promoted in La Fédération Horlogère by Fritz Huguenin, was to establish their own balance spring factory!

Image: La Fédération Horlogère, July 31, 1898

300 watchmakers were said to have signed on to the plan, and the key players moved aggressively to raise the 125,000 francs needed to start a new factory. On July 28, 1898, the Société Suisse des Spiraux (SSS) was officially organized. The group elected Louis-Constant Girard-Gallet (1855-1945), son of Girard-Perregaux founder Constant Girard, as their first chairman. The first secretary was respected La Chaux-de-Fonds watchmaker Paul Ditisheim (1868-1945), best remembered today for the Solvil et Titus brand he later founded. Additionally, Louis Muller (1864-1943) of La Champagne and Ernest Goering of Montres Alpha served as vice presidents.

The company’s official office was a historic villa at Rue du Parc 8 in La Chaux-de-Fonds, which also happened to be home to Girard-Perregaux. Given that Louis-Constant Girard-Gallet was chairman, this is hardly surprising. But spring production was located ad an even more famous address: Chemin de Montbrillant 1. Also called the Montbrillant Watch Manufactory, this new hillside factory was also home to Léon Breitling and Charles Couleru-Meuri!

Image: Indicateur Davoine, 1900

But the Société Suisse saw that a larger facility was needed to break the control of the cartel. A motion was taken up at the very first general meeting to set up a second factory in Geneva, closer to many of the member watchmakers. The group moved quickly to begin production there in a new building at Rue Coulouvrenière 40 under director Eugène Golay. This location would prove so successful that, after a short stint in a small room at Charrière 23, the La Chaux-de-Fonds factory was closed for good.

The Coulouvrenière district was located next to the Rhône power plant known as the Bâtiment des Forces motrices, which originated the famous “Jet d’Eau” that has become a symbol of Geneva. Number 40 housed the SSS factory for decades, along with makers of hands, glass, and other related items. Many watch component makers, especially those involved in production of precious metals, were concentrated at the large factory known as Usine Genevoise de Dégrossissage d’Or, also located on the street. FSR and SSS were eventually united at a building located across the river in the Saint-Jean district.

Image: Walter Mittelholzer 1919

The Rebellion and the Resolution of the Crisis

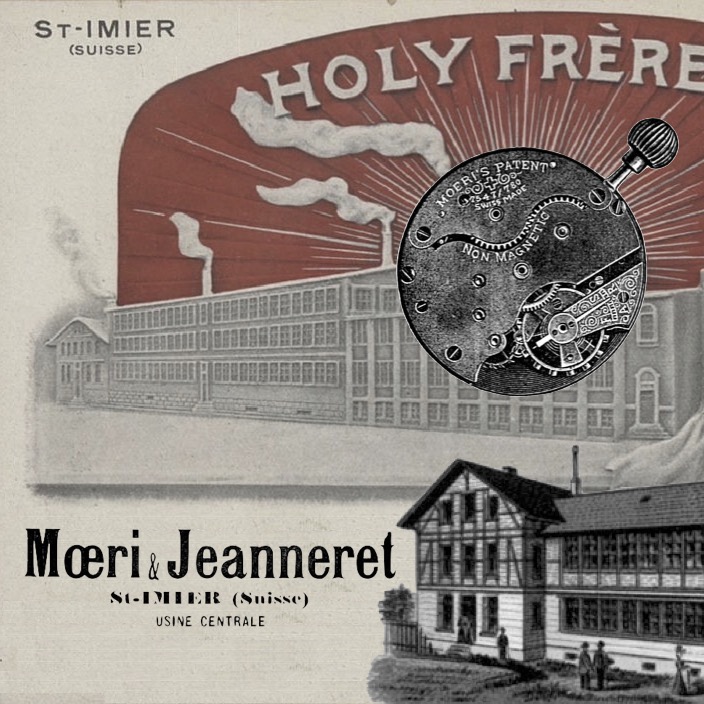

The Société Suisse wasn’t the only response to the Spiraux cartel, of course. A large number of small spring makers appeared across Switzerland in the years after 1895, and some were strong enough to survive and compete for a decade or two. Most notable of these rebels were Emile Schweingruber (1868-1936) in Saint-Imier, and Indicateur Davoine publisher Alphonse Gogler (1866-1945), the savvy and technical Gustave Ulrich (1893-1958), and the independent-minded Ernest Dubois (1896-1968) in La Chaux-de-Fonds. But eventually each was forced out of business or absorbed by the balance spring cartel.

Another challenge to the FSR was technological. The very same year that FSR was formed, a new material was perfected that promised to revolutionize the construction of springs and balances. Known as Invar, it was created by Swiss physicist Charles-Édouard Guillaume (1861-1938), who won the Nobel Prize for his work. Although Invar springs and balances took longer than expected to come to market, the promise of new materials softened concerns about the cartel’s dominance. Steel remained dominant until Nivarox, created by Reinhard Straumann (1892-1967), became the balance spring material of choice after the 1930s.

Ultimately the solution to the cartel crisis was political. With the FSR remaining the dominant maker of springs through World War I and the crisis that followed, the idea of an industry cartel gained support. Ebauches SA, formed in 1926, explicitly followed the template of FSR, with the primary makers of basic watch movement joining forces to help weather the ups and downs of their industry. Then, in 1931, the makers of watches joined forces in a “super-holding” company known as ASUAG, which incorporated Ebauches SA and FSR as well.

ASUAG gained backing from the Swiss Federal Council in the 1930s, restricting the ability of non-members to produce and sell watch components, especially internationally. Soon every maker of balance springs (including SSS and Nivarox) was absorbed into ASUAG, and this gave the cartel a powerful tool to control the industry. It was nearly impossible to produce watches without their springs, so cartel dissidents fell one by one, joining Ebauches SA, FSR, and ASUAG rather than continuing to struggle against it.

The Grail Watch Perspective

The cartel crisis was one of the most important events in Swiss industrial history and the lessons learned from the sudden appearance of the Fabriques de Spiraux Réunies in 1895 guided the industrial development of the country through the 20th century. Although despised and feared at the time, the creation of a cartel was ultimately successful in preserving and protecting small Swiss producers. The move was duplicated by Ebauches SA, ASUAG, FAR, FBR, SSIH, and (thanks to powerful political and economic cover from the Swiss government) maintained the status quo through World War II and the post-war boom. Today’s Swatch Group, which can trace a direct line to FSR, would not exist if not for that radical decision in 1895.

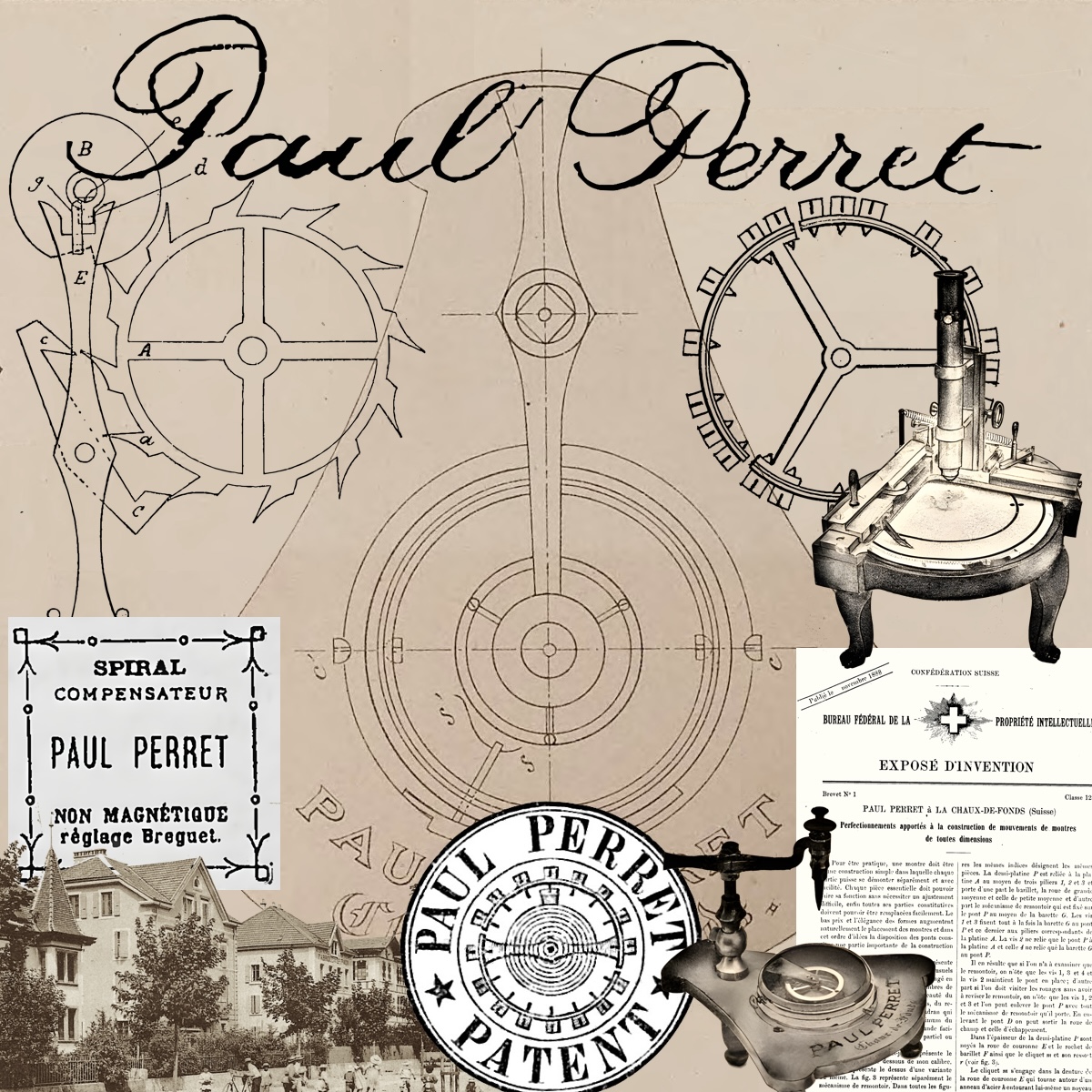

Future articles will discuss the rebellion against the cartel, the invention of Invar by Paul Perret and Charles-Édouard Guillaume, Reinhard Straumann’s Nivarox, and the creation of ASUAG.

References

The balance spring cartel crisis is well-documented in the pages of La Fédération Horlogère and reflected in the establishment and dissolution of the businesses involved. It was has also been covered by academics, notably in the following papers:

- L’industrie horlogère suisse, son organisation et son importance dans notre économie nationale, Eugène Péquignot, 1943

- L’horlogerie suisse, une industrie en pleine transformation, Karl Obrecht, 1968

- The Future of the World Watch Industry, Pierre Hostettler, 1976

- La cartellisation de l’horlogerie suisse (1928- 1931): un mécanisme de production d’inégalités?, Johann Boillat, Frédéric Noyer, 2010

- Contrôler la dissidence: Naissance et évolution du cartel horloger suisse (1931-1941), Johann Boillat, 2011

- Transferts technologiques et district industriel dans l’Arc jurassien (xixe-xye siècles), Johann Boillat, 2019

Statement of the Société des Fabriques de Spiraux Rèunies

“Some of our establishments were going from deficit to deficit, the others were just barely making ends meet and we were all heading for ruin. This 100% that is thrown at us as an enormity is essential to the execution of our program. Moreover, it only represents around 3 centimes per hairspring; three centimes per watch, on an essential and most delicate part. You can see the time on a dial with an ugly hand; You cannot adjust a watch without a good hairspring. The escapement and the hairspring are the soul of the watch.

November 1895 statement from the Société des Fabriques de Spiraux Rèunies

“Our workers had unfortunately arrived at a situation just as precarious as ours. Our first care will be to increase their salaries by 10% and add a special bonus, proportionate to the length of their stay in our establishments. Until now, in some factories, the workers paid half the premium for insurance against accidents in the future, and the company will take charge of this fund. Finally, we are going, in accordance with our statutes, to deduct annually, from our profits, a certain sum, which will be devoted to the foundation of an aid and retirement fund in favor of our workers.

“We won’t surprise anyone by declaring that the continuous fall in selling prices would have inevitably resulted in a drop in quality. We will dedicate all our care to improving the quality of the hairspring, this essential part of the watch. Until now, the failed or imperfectly successful springs were sold at a discount, either at home or abroad: From today, that part of the production will be destroyed.

“All this will absorb a significant part of the profit made thanks to our new tariffs – whose prices are those of ten years ago – and will simply put us in a normal situation: We would have no trouble giving any the proof. A smaller increase, of 50% for example, would not have enabled us to achieve our general goal, it cannot be repeated too often, and would have been simply borne by the adjusters, against all fairness. These three cents will oblige them to raise the price for adjustment and they will pass this on to increase that the watch will undergo.”

Leave a Reply