La Chaux-de-Fonds is sometimes called “Watch City” because it is home to so much watchmaking history. It is said that “Chaux-de-Fonnier” factories produced half of the world’s watches in the first half of the 20th century! It’s no surprise that some historic sites are forgotten, but the Palais Invar deserves a closer look: It was one of the most recognizable buildings in La Chaux-de-Fonds for most of the 20th century, housing brands like Montre-Invar, Alpha, Venus, Le Phare, Sultana, and Jean d’Eve, and it was home to the first Salon Suisse de l’Horlogerie in 1933. Yet Léopold-Robert 94 is not included in the “Urbanisme Horloger” walking tour of La Chaux-de-Fonds and is mostly overlooked today. Let’s rectify this situation!

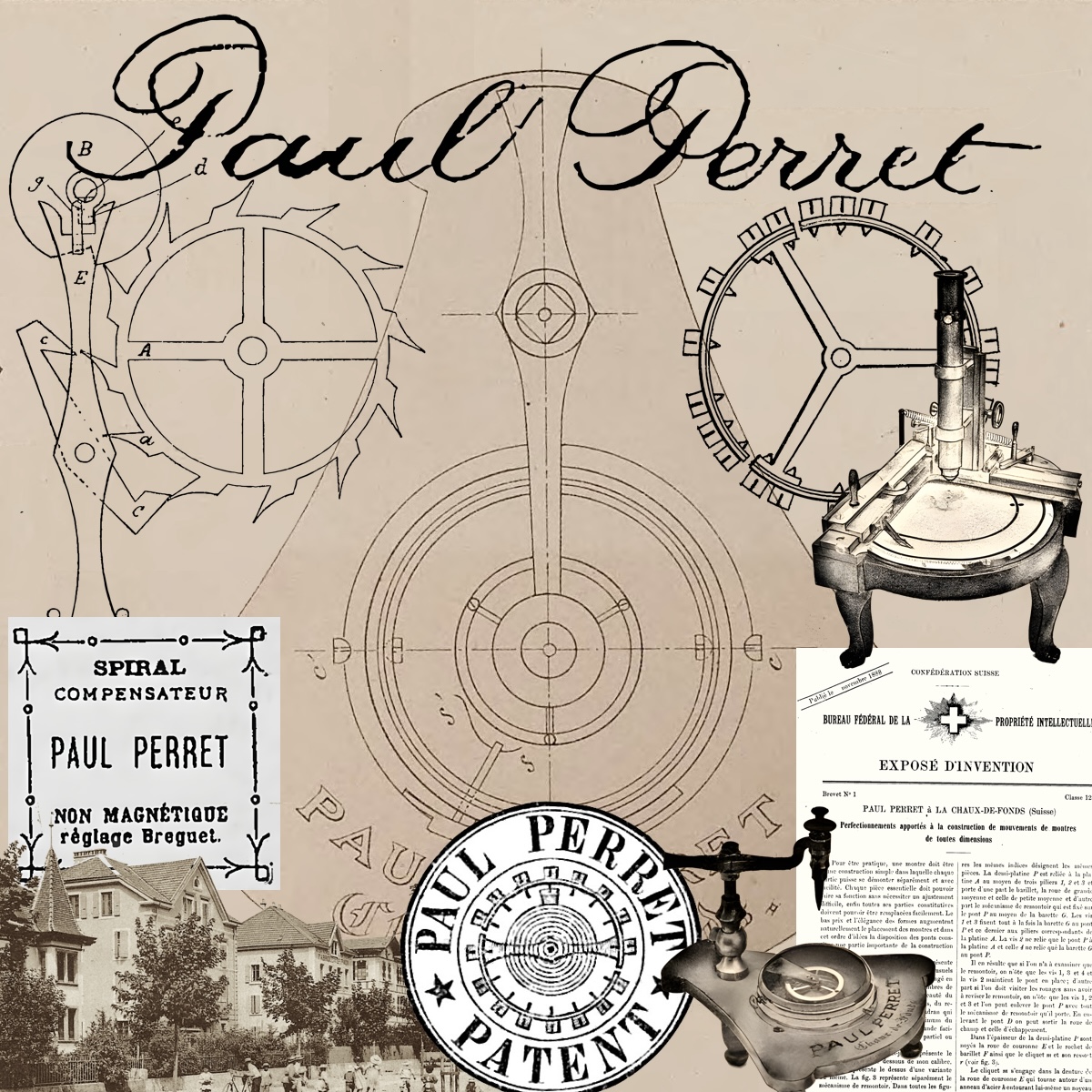

Learn the origin of the term Invar and the controversial career of Paul Perret!

Achille Hirsch’s Montre-Invar

Although mostly forgotten, the watchmaking and export business established by Achille Hirsch and his sons was one of the most successful in La Chaux-de-Fonds before World War II. The Hirsch family’s watch businesses grew from component production to the manufacture of whole watches in the city under a wide variety of names, notably including Vigilant, Cervine, and Invar. Achille and Rachel Hirsch are more remembered for their promotion of the Jewish community in the region, which is a fitting legacy for the family.

Achille Hirsch (1847-1927) was a watch merchant active in La Chaux-de-Fonds around the turn of the century. Originally from Alsace, Hirsch was one of the many Jewish émigrés who moved to the region despite a history of persecution and exclusion in Neuchâtel. Hirsch had been a farmer but became interested in watchmaking when he arrived in La Chaux-de-Fonds around 1874. After 20 years spent manufacturing watch cases and dials for others, Hirsch became a manufacturer of complete watches by 1896.

In 1899 Hirsch established the Vigilant Watch Manufactory to expand production of watches. The following year, Achille and Salomon Hirsch (both his cousin and brother in law) answered the call from the village elders in Tavannes to build a new factory in the city, their second. (Someday I will write a closer look at the so-called Nouvelle Fabrique de Tavannes!) Just three years later he built a third factory across the tracks from the historic center of La Chaux-de-Fonds, as well as a luxurious villa for his family.

Montres Invar was yet another company he founded. Established in 1902 by Achille Hirsch and Félix Hirsch, who was also part owner of Vigilant, Invar produced higher-end watches. The firm used the slogan “précision chronométrique” in advertisements, though they were still offered at accessible prices. The name came from the new alloy by Charles-Edouard Guillaume and popularized by Paul Perret for use in balance wheels and springs, though the company was not directly tied to this effort. A 1927 letter suggests that the affable Guillaume was amused but not bothered by the company taking the name of his alloy.

Hirsch’s Vigilant Watch Manufactory was incredibly successful, with dozens of brands for export markets around the world. His sons took over the company by 1913, and they undoubtedly thought this success would continue forever. Seeking new clients and distributors, Vigilant and Invar shared a high-profile showroom in the new post office building near the railroad station. But the best watch firms were building landmark buildings to the west of the city center: Braunschweig (Election), Didisheim (Marvin), Ditisheim (Vulcain), Eberhard, Picard (Invicta), Schild (Hebdomas), Schwob, and so on.

The Rise of the Palais Invar

The boom in watchmaking after World War I made the watch producers of La Chaux-de-Fonds feel invincible, with insatiable demand for their products worldwide. The Hirsch brothers (Jules, Jacques, and Maurice) selected a location at the corner of Avenue Léopold-Robert and Rue de Pouillerel, which was occupied by grand garden and villa that did not fit into the city’s emerging grid. An early photography studio was located at number 94, while a large sign directed visitors to the office of the Tavannes Watch Co, located a few blocks away at Numa-Droz 156. All of this was to be dismantled, leaving the prime location available for development.

Thus it was that the so-called Palais Invar opened around 1922. Number 94 Avenue Léopold-Robert is a few blocks west of the Hôtel des Postes and train station, and less than a block from the new headquarters of Invicta, Movado, and Eberhard. The Hirsch family could see the domed showroom across the railroad tracks, just as they had watched the many other watch factories appear in the city. Importantly, the building was highly visible as passengers emerged from the railroad station and rode the city’s streetcar line.

Unlike many of the new watchmaking buildings in La Chaux-de-Fonds, the Palais Invar was not a factory. Rather it was a showroom, with a large open space on the ground floor allowing visitors (mainly distributors and partners) to view the Invar watch line in comfort. It focused much like a booth at a watch fair and can be seen as a predecessor to the modern watch boutique. And it certainly functioned in this manner for Montre-Invar, though sadly for less than a decade.

The Fall of House Hirsch

The post-war boom did not last. European countries that were devastated during World War I worried that they would never again be competitive in industries like watchmaking if imports from countries like Switzerland were allowed. The tariffs imposed after 1920 hit the Swiss watchmaking industry especially hard, with many producers exporting incomplete watch components to circumvent these restrictions. This caused panic in Switzerland, which feared the loss of this critical industry to factories abroad. Facing calamity, the factories in La Chaux-de-Fonds stopped production, laid off workers, and closed their doors.

So it was with the Hirsch brothers. Even their deep industry connections and diversified product portfolio could not save the firm, which was nearly bankrupt by 1926. Desperate for a lifeline, the brothers opened a line of credit from the Banque Cantonale Neuchâteloise secured against their father’s company. Yet they were still unable to stay current with this new loan, so the brothers negotiated a debt-reduction agreement with the bank. Such deals were unpopular with the average Swiss worker, who found himself in similar financial distress. A judge rejected the agreement as too favorable to the family and in 1930 they were forced out of their namesake company, S.A. des Usines Fils de Achille Hirsch & Co.

Undaunted, the brothers immediately established a new company, confusingly called Fils d’Achille Hirsch & Co. When the court rejected this name, they re-branded the firm as Cervine SA: “Hirsche” is the German name for the common fallow deer, which is called “Cervine” in French! The new company soon purchased the Vigilant and Invar brands from the former bankrupt entity and the Hirsch family was back in business. They initially operated out of a building near the center of town before moving into the old family factory adjoining their home. But the Palais Invar was no longer associated with its namesake company.

Exposition d’Horlogerie Ancienne et Moderne, 1932

With the city’s primary industry nearly at a standstill, some said it was the end of watchmaking in La Chaux-de-Fonds. But the city’s boosters of the industry decided to hold an exposition to showcase the historic and current watches produced there. They hoped that this event would revitalize both civic pride and the once-active watchmaking industry. The economic development authority of La Chaux-de-Fonds selected the now-vacant Palais Invar as the site for this expo, since it was built and furnished as a showroom for watches.

The exposition featured both historic watches and clocks from the Neuchâtel region and modern products from businesses in eight categories: Watchmakers, case makers, engravers, dial makers, plating and gilding, spring makers, leather workers, and graphic artists. The historic exhibit included items from the museums in Le Locle and La Chaux-de-Fonds as well as the private collection of Maurice Robert, director of the FHF factory in Fontainemelon.

The exposition ran from August 27 to September 25, with opening speeches from organizer Julien Dubois, Federal Councilor Edmund Schulthess, Cantonal Councilor Alfred Clottu, and City Councilor Paul Staehli. It was reported to be well-attended, with groups traveling from France (including famous actress Gaby Morlay), Italy, and Spain (Alfonso XIII, the recently dethroned King of Spain, and his son). The exposition was widely covered in the local and national press, with detailed stories covering the historical watch and clock exhibits in particular.

Industry booster Marius Fallet, writing in La Fédération Horlogère, does note that certain industries were not well-represented. The makers of case components “did not think they had to make a slight sacrifice in a spirit of common watchmaking solidarity. It is very regrettable.” Even so, he notes that the Expo “will all together be magnificent, lively and captivating.” The bustling crowds and constant press coverage did much to give the people of the city something to look forward to.

Even the writers of the socialist La Sentinelle, traveling across the street to visit the Exposition, were rapturous in their praise. Although criticizing the heat and cramped spaces inside the Palais, they were thrilled to see the musical performances and festivities open to all of the workers, many of whom had been idle for months. They did complain that the public swimming pool nearby had been torn down to make way for a parking lot, however. And they thrilled that the exposition showed the talent of skilled craftsmen, as opposed to the crude mass-produced pieces from the “old bosses.”

Image: Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie, September 1932

Although no photography was allowed in the hall of modern watches we do get a hint of the novelties displayed there:

- The art-deco movement had arrived: “Thin movements in ultra-flat cases … line winning out over colour … white gold has developed unbelievably … the chrome plating and the stainless steel case take precedence over the gold case.”

- Notably, this may have been the first appearance of the new Reverso: “The reversible watch has met with some success.”

- Then there were new technical capabilities on display: “The flowering of self-winding watches, inspired by a process devised by the great Breguet himself, watches with watertight closure, parts capable of finally resisting all shocks and be easily repaired.”

- Another trend noted was jumping hour watches, which came from many makers in these years.

The Salon Suisse de l’Horlogerie, 1933

The Exposition d’Horlogerie was considered such a success that a new company was formed on October 2, 1932 to perpetuate the tradition of an annual watch expo in La Chaux-de-Fonds. Operating under the name Salon Suisse de l’Horlogerie, this organization sold shares, priced at 100 francs each, to members of the watchmaking industry and interested members of the public. The board of directors was headed by professor Julien Dubois, founder of the 1932 Exposition, who was joined by Georges-Emile Eberhard (Eberhard & Co.), Councilor Hermann Guinand, Adrien Schwob (Schwob Frères), Arnold Gerber (editor of l’Impartial), Samuel Guye (director of the watchmaking school), Alphonse Gogler (publisher of Indicateur Davoine), and other notables.

The natural home for the Salon Suisse de l’Horlogerie was the Palais Invar. But the event was expanded to also include three temporary pavilions erected nearby: Two (across the street) housed producers of watch components while the third was a canteen capable of housing 600 diners! The organizers invested a great deal of money into the Invar building, hoping to establish it as the home for an ongoing annual event. This included installing better “windows” for display of modern watches and ventilation to address the “African warmth” noted in 1932.

Exhibitors at the Salon Suisse included many famous names that would be recognized today: Audemars Piguet, Bovet Frères, Breitling, Cortébert, Eberhard, Invicta, Juvenia, Léonidas, Martel, Marvin, Movado, Piaget, Record-Dreadnought, A. Reymond, Schwarz-Etienne, Solvil, Tavannes, Vulcain, and Zénith. Notably absent were the Hirsch companies (Cervine, Invar, Vigilant) who called the building home just a few years earlier: The Hirsch brothers were still struggling to re-establish their father’s business.

The Salon Suisse opened on August 26, 1933, and closed on September 18. It was inaugurated once again by Edmund Schulthess, who was President of the Swiss Confederation for that year. Among the guests on thee first day was Charles-Edouard Guillaume, inventor of the Invar and Elinvar alloys. Although he was not bothered that the Hirsch family had co-opted the brand name of his revolutionary material, he must have been somewhat amused to sit in their “palace”!

The commercial aspects of the event were emphasized in an attempt to re-start the Swiss industry which was still suffering in the depression era. But an impressive historic collections belonging to Mr. Loup of Geneva and Mr. Seiler of Vevey drew attention as well, including 150 watches and clocks from Switzerland, France, and England. The most notable historic artifact was mostly overlooked at the time, but its presence there had lasting significance: A pair of bracelets produced by Parisian jeweler Nitot for Empress Joséphine of France were exhibited by their owner, Auguste Seiler. Their appearance at the Salon established the modern claim that Nitot’s bracelet was the very first wristwatch!

A major shadow over the manufacturers was the presence of ASUAG, Ebauches SA, FSR, FAR, and the rest of the newly-formed holding companies. Although heaped with praise in the pages of La Fédération Horlogère, one can read between the lines that these groups threatened the smaller producers and individual workers visiting the Salon. The Swiss government had recently allocated 13.5 million francs to enable the group to purchase struggling factories to add to its portfolio. This would prove to be both a blessing and a curse for the industry and presaged the moves made by Hayek in the 1980s that lead to today’s dominant Swatch Group.

What To Do With the Palais Invar?

After a successful 1933 Salon, which attracted throngs of visitors from both near and far, the question arose of what to do with the Palais Invar when it was not hosting events. The large main room was offered for use by local groups, with the Ping Pong Club “Sapin” being a frequent guest in the 1930s. Other users were not so welcome: Rumor spread that a Swiss branch of the Italian Fascist movement was planning to hold meetings there and this was quickly obstructed by the predominately socialist and anarchist city residents. The next prospective tenant, the Christian Science church, also caused a stir but ultimately failed to materialize.

And what of the next Salon? Initially announced to be returning to the Palais Invar, the committee decided instead to move the 1934 event to the nearby Musée des Beaux-Arts when that venue was offered for use free of charge. Sadly this second Salon (the third annual watch show) would be the last. Declining attendance and a still-poor economy meant that there would be no 1935 edition. Remarkably, the committee continued to raise funds to pay back all of the original investors, a task they achieved in 1953!

Schwarz-Etienne

The Palais Invar must have left an impression on at least one exhibitor.

Paul Schwarz was a small-scale watchmaker who opened his own home workshop in La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1905. Specializing in jewelry watches for ladies, Schwarz was a master at working with movements as small as 5 ligne (11.2 mm or less than half an inch) across. He married Olga Etienne by 1912 and their names continue to this day with one of the most respected independent watch movement makers: Schwarz Etienne.

Paul Schwarz-Etienne’s sons (Gaston, Herbert, and Henri) joined the firm during the war and pushed to enlarge it. They moved the business from the family home into a dedicated workshop and expanded production despite the bad economic times. Paul Schwarz-Etienne retired following Olga’s death in 1931, but by the time of their exhibit at the Salon in 1933, the firm was well-known for top-quality watches at affordable prices. Their focus on smaller, thinner, and higher-quality watches meant that they escaped the attention of ASUAG, which was quickly buying up most mainstream watch producers.

The sons needed a new headquarters for their family firm and the vacant Palais Invar must have seemed a perfect fit! By November of 1935 the company, now known as Fils de Paul Schwarz-Etienne, moved in. Just a month later, Gaston and sister Helyette purchased Montres Sultana, which operated independently for the time being but would move in as well. Another independent company, Astin Watch, relocated to the former Palais Invar in 1937, and the Schwarz brothers purchased that too in 1944. Gaston Schwarz had executed a takeover of Le Phare, a historic maker of complicated watches from Le Locle, in 1941, and that too eventually called the Palais home.

Schwarz-Etienne focused on the Alpha brand in the 1940s, and this was proudly displayed at their headquarters. As seen in this 1949 advertisement, the building was no less stylish and iconic 25 years after it was first built. And the photo below confirms that the facade proudly wore the Alpha brand name at this time, though the city was being built up around the low Palais building.

By 1952 the building was extended along Léopold-Robert to include number 96 as well. The former location of the Salon canteen, this had been a vacant lot until this point. Gaston moved the offices of Sultana to the new wing while Astin and Schwarz-Etienne remained at number 94 alone.

There had been some controversy over their use of Alpha, as Montres Alfa was an unrelated watch company in Lucerne founded in 1933. Although Schwarz-Etienne registered both Alpha and Alfa as trademarks in 1935, a watchmaker by the name of G. Kessel was using the names as well. Despite a number of threatening notices, it seems that the brothers decided to move on with another brand name.

The company’s favored brand for the 1950s was Venus de Milo (or just Venus). This was a surprising choice given that it was also the name of a well-known maker of watch movements in Moutier! They had registered the name in 1930, but the movement maker (which was absorbed into Ebauches SA in 1928) had already been using the name. Presumably some arrangement was reached, as there seems to have been no warnings published for this brand.

As the 1950s progressed, tragedy hit the second generation of the Schwarz family. The eldest brother, Gaston, had been in poor health and died in 1952. He must have seen this coming, since he had been passing control of his many businesses to others, including his sons Gaston (who got Astin) and Frédy (Sultana and Le Phare) and his younger brothers Herbert and Henri. But Herbert and sister Helyette died suddenly in 1955, just two days apart. Henri took on management of the family firm as Herbert’s son André became more involved with Astin.

Despite this confusion of companies, most were headquartered at the former Palais Invar. As shown at right and below, the Astin name decorated the facade later in the 1950s, though it is unknown which brand was used below the dome. Sultana used the extended wing with its own entrance and signage, and Le Phare remained headquartered across town.

Le Phare and Jean d’Eve

Through the 1960s, the next generation of the Schwarz family consolidated operations at the expanded Palais at Léopold-Robert 94 and 96. The family watchmaking interests roughly aligned with the three brothers’ families:

- Gaston Schwarz: Following his death in 1952, his sons Gaston and Frédy focused on businesses he had acquired and which were inherited by his widow Marguerite: Le Phare and Sultana

- Herbert Schwarz: After his 1955 death, Herbert’s widow Hedwige was chairwoman of Astin, with their son André administering that company.

- Henri Schwarz: The youngest son was now the eldest member of the family, so he focused primarily on Paul Schwarz-Etienne’s namesake company, using the Venus and Alpha brands.

In 1961, Gaston and Frédy consolidated Le Phare and Sultana at the Palais, with all of the family’s companies now filling the extended building along Léopold-Robert. This would remain the case through the 1973 merger of Le Phare and Sultana and the launch of a new brand, Jean d’Eve, in 1981. This came after Henri, last of the Schwarz brothers, died in 1976. The company was renamed Le Phare-Jean d’Eve SA in 1984, with Gaston’s son Jean-Claude Schwarz joining management.

Jean d’Eve had some time in the sun in the 1980s, launching a number of popular and innovative models. Their Spinnaker line had a rope-like bezel, which drew attention along with similar nautical themed models. The firm also continued production of Le Phare’s Sectora, which featured attention-grabbing retrograde hands. And then there was the Jean d’Eve Samara, one of the first kinetic-winding quartz watches, one of which sits in my own collection. All of these were produced and sold under the dome of the iconic Palais in La Chaux-de-Fonds.

The family’s namesake firm, Schwarz-Etienne, continued under a new generation of Schwarz family leadership as well and began selling watches under their own name in 1985. It was taken over by Neuchâtel-based real estate mogul Rafaello Radicchi in 1993, and he dropped the hyphen giving it the modern name of Schwarz Etienne. In 2007 Marc Barrachina announced that the firm would re-establish in-house watch movement production, and the company launched a micro-rotor automatic movement in 2009. The company later re-focused on production of these “irreversible” movements for the burgeoning OEM business under Mauro Ergemini. Today Schwarz Etienne is widely respected for their excellent complicated and micro-rotor movements.

Le Phare-Jean d’Eve was sold to Hong Kong-based Renly Watch Manufacturing in 1991. When Jean-Claude left the firm 1995 it represented the end of three generations of Schwarz family involvement in the 60 years since Helyette and Gaston had taken over Sultana. The building at the corner of Léopold-Robert and Pouillerel in La Chaux-de-Fonds still wears the Jean d’Eve name, though it is unclear how active the company remains.

The Grail Watch Perspective: The Business of Watch Sales

Over the last century the watchmaking industry transitioned from the realm of craftsmen to the battle of companies to the marketing of brands. And the Palais Invar, on the corner of Léopold-Robert and Pouillerel in La Chaux-de-Fonds has hosted this marvelous and difficult metamorphosis. Despite sharing the city with landmarks like the Eberhard factory, Montbrillant, Girard-Perregaux, and the modern Musée Internationale d’Horlogerie, the Palais Invar deserves notice and respect. Over the last century it presided over the greatest forgotten watchmaking firm (Montre-Invar), the first Swiss watch exhibitions (the Salon Suisse de l’Horlogerie), and the rise of one of the great family watchmaking firms (Schwarz Etienne). I will certainly stop by the Palais the next time I am in La Chaux-de-Fonds, and I urge you to do the same!

Additional Material

As usual, there was much more material that could have been added. So I present a gallery of supporting information and articles for readers to enjoy if they wish to dive in further!

1932 Exposition Advertisements

1932 Exposition Articles in l’Impartial by Paul Bourquin

1932 Exposition d’Horlogerie Description by Marius Fallet

1932 Exposition d’Horlogerie Description by Alfred Chapuis

1933 Salon Coverage in La Fédération Horlogère

Other 1930s Tenants

Bonjour monsieur

Je possède un bracelet-montre de la marque ” Star Suisse ” produite dans les années 1940 et j’aimerais vraiment connaître son histoire.. à savoir qui la conçu etc .. elle est d’une beauté exceptionnelle ( or platine diamants ) je peux vous envoyez des photos par mail si vous voulez.. Voici mon adresse mail :

[email protected]

Je vous remercie vivement par avance !!

Bien à vous