The story of Paul Perret is quite unusual: He was famous not for one single accomplishment but for three different ones: He revolutionized watch adjustment, registered the very first Swiss patent, and contributed to the only watchmaking-related discovery to win a Nobel Prize! Perret was incredibly controversial in his time, vilified and then embraced by his peers, yet there is little record of his life. Read on and discover why Paul Perret deserves to be remembered!

Learn about the unrelated watch company, Montre Invar, and the first watch boutique in La Chaux-de-Fonds!

Three Moments of Fame

Most of the people in watchmaking labor in obscurity, never getting credit for their contributions. The nature of the Swiss people is partly to blame: They do not love attention-seeking behavior and prefer to let their works speak for them. My writing at Grail Watch and elsewhere tends to cast a light on these unsung heroes of the industry, though it is often difficult to uncover their stories.

Before I tell the story of his life, let us briefly enumerate the remarkable yet controversial contributions made by Paul Perret:

- In his 20s, Perret invented essential machines for the adjustment of a watch balance and spring. This made him infamous, as his friends touted the incredible speed at which he could tune a chronometer using his Talantoscope. This self-promotion was widely ridiculed as non-Swiss, but threats against him became more serious when it was rumored that he would sell his device in America!

- In his 30s, Perret was an outspoken proponent of the establishment of a system of patents in Switzerland. He was ultimately successful in his campaign, and camped out overnight to receive Swiss patent number 1 on November 15, 1888. But he was once again called a narcissist after he also collected patents 21, 22, 23, and 24 that day!

- In his 40s, on May 11, 1898, Perret took the stage at a meeting of the entire industry as it struggled under the balance spring cartel. He announced that a nickel-steel alloy called Invar, developed with Nobel Prize-winning scientist Charles-Edouard Guillaume, was immune to the variability of temperature and could be produced outside the cartel. Perret became a hero to the industry but his springs only went into production after his death in 1904, and then by the very cartel he sought to undermine.

Any of these contributions would warrant an article in Grail Watch, but it is incredible that all three came from the same man. The fact that he was such a controversial figure yet quickly cast aside by the industry also drew my attention. Let us consider the man called “shameless” and “savior”, “threat” and “failure” in his time!

Farmer, Soldier, Watchmaker

Paul Perret was born in 1854 in the village of La Sagne. Situated in the same valley as Les Ponts-de-Martel, the town was one of many that supplied watchmakers in Le Locle and La Chaux-de-Fonds on the other side of the mountain to the north. Like most residents, the young Perret worked as a farmer in the summer and spent the winter producing components for watches by hand at the family workbench. His was a large family and was very well-connected to others in the area, which was the home of pioneering 18th century watchmaker Daniel JeanRichard dit Bressel.

Although he was unable to regularly attend school, Paul Perret was gifted with his hands and earned a spot as a watchmaking apprentice in La Chaux-de-Fonds at the age of 17. His skills were quickly evident, and he was recruited by the Fabrique d’Horlogerie de Fontainemelon in 1874. The village of Fontainemelon must have felt like home to the 20 year old Perret, but it is unclear how well he got along with technical director Edouard Junod, who would run that important factory for nearly 4 decades. Most likely Perret was unhappy to be focused on manufacturing rather than the skillful and careful adjustment of watch movements.

Perret returned to La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1877, renting a home with a workshop and opening his own business as an adjuster of chronometers the following year. There were many such businesses in the watchmaking city, as movements were still quite rough at this point, with the hand-made wheels and pivots requiring rework before they could be used. Perret specialized in the escapement, balance, and balance spring, an elite trade.

The young Paul Perret stood out for the speed and accuracy of his adjustment: He could turn around a chronometer in just a few hours! After a few years he revealed that he had been developing machines to assist in watch adjustment since 1875, and these would propel him to notoriety in his industry.

Paul Perret’s Automatic Adjustment Machine

Not content to practice his trade as an adjuster of watches, Paul Perret began inventing new tools and machines at an early age. He began working on a machine to assist in the regulation of a balance and spring while still an apprentice in La Chaux-de-Fonds, and perfected the machine by 1877. Later called the Talantoscope, Perret’s adjustment machine gave him an incredible advantage over other adjusters.

It was widely understood that the accuracy of a watch depended on the frequency and amplitude of the balance. But setting these properly depended on numerous factors, including the exact shape and length of the balance spring as well as the poise of the balance wheel. This was confounded by the relatively primitive materials used (Bessemer steel was just emerging) and the fact that most components, notably springs, were cut and shaped by hand. Adjusting the rate of a movement was a painstaking process of trial and error, with each setting checked against a reference chronometer.

Perret’s device simplified this process by allowing direct comparison and adjustment in real time. The balance to be adjusted was held directly above a reference balance under glass. Thus, any variation of frequency and amplitude were immediately and obviously visible. The spring was mounted on a tweezer that could be easily adjusted to grip the balance spring at different locations until the optimal point was found. The spring would then be kinked and permanently set.

This machine allowed Perret to adjust balance springs so efficiently that he could singlehandedly handle large orders that would swamp every other adjuster in town. The entrepreneurial Perret set up an “atelier de réglages” on the fashionable Rue du Parc in La Chaux-de-Fonds, directly across from the railroad station. It was said that he delivered an astonishing 200,000 Breguet settings to the industry between 1878 and 1888, nearly 300 per workday!

Perret soon dominated the trade, and became very rich in the process. By 1884 he was able to purchase a large house with a garden along the fashionable and growing Avenue Léopold-Robert. His house was located at number 68, just a block down from his workshop at Rue du Parc 65.

A young gentleman about town, Perret became involved in many social and civic positions. He served on the commission of the watchmaking school in La Chaux-de-Fonds, joining the elite of the industry including his old boss from FHF, Auguste Robert. He also served on the board for the national exhibition and Tir Canonale, a shooting competition. And Perret joined the military, becoming a First Lieutenant in 1881 and Major of the Infantry in 1889. His skill with the revolver was so renowned that he became known as the “King of the Tir!”

In 1884, Perret requested the Government of Neuchâtel to transmit the time signal from the telegraph office in La Chaux-de-Fonds to his workshop. Professor Adolphe Hirsch of the Neuchâtel Observatory handled the installation of the line to Perret’s shop at Rue du Parc 65 and it was operational by April 26 of that year. This was the first private use of the Observatory’s telegraph time signal, and Hirsch and Perret remained friendly until his death 20 years later. It seems that Perret allowed other adjusters to use the signal in his workshop, as noted by a Dr. J. Hilfiker the following year.

In the 1880s, Perret invented another consequential machine for the production of balance springs. His Campyloscope was a specialized pantograph for the shaping of balance springs. Stencil forms were placed on the bed of the machine and their exact shape could be reproduced in miniature on a steel spring placed under a microscope. Although extremely effective, the Campyloscope was much less controversial. Perret’s basic design continued to be used for many decades by watchmakers worldwide, especially in the watchmaking schools that appeared in the 20th century.

Perret continued to invent through the 1880s. He created a novel method to construct a watch using bridges to accurately locate the components. He also created a fine regulation system using a pointer that followed an inscribed snail-shaped track. There was also the Perret Escapement, an alternative to the dominant Swiss lever. And he notably created a split bi-metallic balance wheel in an attempt to combat the effects of temperature variation on the accuracy of a movement. This presaged his focus around the turn of the century on compensating springs in an attempt to solve the same problem.

The Fight for Patents

Although Perret offered his Talantoscope for sale soon after he invented it in the late 1870s, he was careful about who he allowed to purchase one. It was a fairly simple machine and could easily be reproduced. And the Campyloscope quickly became a generic instrument, widely copied in schools and workshops.

The concept of intellectual property was not widely recognized until the 19th century, and even then it was often seen as a tool for the rich or a restraint on invention and trade. The idea that patented inventions must be disclosed publicly and that monopolies would have an expiration date gained traction in Italy and France in the 16th century, with rigorous examination of claims following soon after. The English struggled to find a balance between profit and openness, and the system there was widely abused despite the building Industrial Revolution. It was not until after the French Revolution and the creation of a modern patent system in America that the idea of intellectual property was widely accepted.

Switzerland was quite late in establishing a system of patents and trademarks, with resistance to the concept continuing even into the 1880s. Paul Perret was an outspoken booster of the establishment of a patent system in Switzerland modeled after the French and American systems. In 1882, after the national council failed to enact a patent law, a referendum was held to enact it. When voters rejected this July 30 initiative, Perret convened a meeting of interested groups from across Switzerland to promote another referendum or bill. The Olten Meeting, held in October, brought together luminaries including Ernest Francillon of Longines and the Chancellor of the Canton of Geneva. Still, Perret’s efforts were unsuccessful.

Ultimately the Swiss were shamed into adopting patent protection. During the 1878 International Congress of Industrial Property in Paris, Hungarian-American patent attorney Anthony Pollok called Switzerland “a nation of counterfeiters” (“un pays de contrefacteurs”) due to their knack of duplicating the inventions published in other countries. After the Swiss agreed to uphold the intellectual property protections of trading partners it was only a matter of time before they created protections for Swiss citizens as well. A law to register and enforce patents and trademarks was quietly passed on June 29, 1888, and was ultimately enacted without resistance.

The Swiss Federal Intellectual Property Office was opened in Berne on the grounds of the Asylum for the Blind on November 15, 1888. The irrepressible Paul Perret arrived the day before and was first in line when the doors opened at 8 AM. Thus, he was able to secure Swiss Patent Number 1 for his “Perfectionnements apportés à la construction des mouvements de montres de toutes dimensions.” Edouard Heuer stood just a few steps behind, registering his “Nouveau système de montre, grande sonnerie, répétition” as patent number 9. And Perret was able to re-enter the queue and register four more patents (numbers 21-24) later that day!

Among the other early patent holders were Albert Jeanneret (founder of Excelsior Park and Moeris), a representative from Fabrique d’Horlogerie de Fontainemelon, and Irénée Aubry (inventor of the Hebdomas), who we have covered here. It is likely that all four men stood in line together that November morning in Berne.

Although Perret had many friends and supporters in the Swiss watchmaking establishment, his reputation as an outspoken and aggressive businessman was growing. Many were shocked to see him waiting at the Patent Office in Berne before the sun rose, and his aggressive registration of essential elements of the watch movement put them on notice that he intended to compete in areas beyond regulation. Their patience was soon put to the test!

Amazingly, Perret was already distracted from his growing watch regulation business in La Chaux-de-Fonds. In February of 1888 he turned management of the company over to his father, Numa Perret, and associate Louis-Ulysse Vuille. The firm handled large adjustment orders from watchmakers throughout the city for the next five years but was dissolved after the elder Perret’s death on June 27, 1893.

Pompous Praise for a Charlatan

On June 28, 1889, newspapers across Switzerland published an anonymous letter announcing a remarkable achievement: Thanks to his “very important” yet “secret” invention, Paul Perret was able to adjust 24 balances from inexpensive watches in a single day, delivering 21 which met the “1st class” criteria of the Geneva Observatory. Proclaiming him to be “among the boldest innovators in this industry,” the letter writers claim that “this invention will mark an important date in the history of watchmaking.”

This extraordinary claim was not met with enthusiasm.

Swiss people tend to be reserved, but they can become quite aggressive when provoked. I am not aware of anything in historic watchmaking that compares to the anger, accusations, and incredible sarcasm that followed this open letter!

The “pompous praise” of this letter was compared to “a large American advertisement” as the claims were ripped apart. Obtaining a 1st class certificate from the Geneva Observatory requires 45 days of observation of a complete, cased watch, and no such trial was performed with Perret’s specimens. In fact, it was claimed that two thirds of the movements actually failed at day 17, so the test was cut short. A representative of the Observatory confirmed their participation in the experiment but also these failures.

Perret’s promoters quickly folded in the face of such criticism, acknowledging the folly of their initial anonymous letter. They revealed themselves as Albert-H. Potter and Berthold Pellaton, and claimed to have promoted Perret’s work to prod him to promote himself more heavily! They also promised to publish the data behind their claims in Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie, which they did a week later, both there and in the ordinary newspapers.

But the accusations continued, with many seeing a connection between Perret’s promotion of patents and his revolutionary machine. They accused him of attempting to withhold his invention from his Swiss critics to favor the burgeoning American watchmaking industry! This accusation forced a response, with Perret himself promising to make the device openly available to Swiss watchmakers.

Given the emotional response to Perret’s claims, it is surprising that the controversy quickly faded. He licensed his secret device, which proved to be little more than an improved Talentoscope, to Paul Jeannot of Geneva, who set up a business in La Chaux-de-Fonds to regulate watches using the technique. And so the controversy was resolved for a time.

Perret and Jeannot worked together to produce watches as well. Perret licensed Patent CH1 to Jeannot and shared ownership of a number of patents with him through the 1890s. These included an improved chronograph mechanism, a replaceable balance cock (precursor to the porte-echappements that gave Portescap its name), and an improved independent seconds hand mechanism. Paul Jeannot was the son of a watchmaker from Les Brenets near the border with France who set up a watch factory in Barcelona before expanding in Switzerland. But the 1890s Jeannot junior was trying to grow the family business but was beset by the emerging unionization of workers, who rejected his paltry pay rates. He was arrested in 1895 related to the bankruptcy of his factory, which likely spelled the end of Paul Perret’s participation in the business.

Guillaume and the Invar Balance Spring

Given the importance of chronometry in many fields of science and the incredible progress in watchmaking over the last 150 years, it is somewhat surprising that there has only ever been a single Nobel Prize awarded in the field. Charles-Édouard Guillaume received the prize in physics in 1920 “in recognition of the service he has rendered to precision measurements in Physics by his discovery of anomalies in nickel steel alloys.” Yet the humble Guillaume was happy to share credit for this discovery with one of his fellow Neuchâteloise: Paul Perret!

Guillaume was a remarkably dedicated scientist. Born in Fleurier, Canton Neuchâtel, in 1861, he proved his ability while studying engineering at the Federal Polytechnic School in Zürich (ETH). After graduation, Guillaume relocated to Sèvres near Paris to join the International Bureau of Weights and Measures in 1883, where he spent his entire 5 decade career. Guillaume was attracted to Pavillion de Breteuil to contribute to the standardization of the metric system. He was assigned to develop a less-expensive prototype of the meter, then constructed of iridium platinum, for use in surveying. Working with the steelmakers at Imphy, Guillaume discovered the variable magnetism and coefficient of expansion of certain nickel steel alloys.

Realizing that nickel steel could have many applications beyond metrology, Guillaume shared his findings at public scientific conferences. Paul Berner, head of the watchmaking school in La Chaux-de-Fonds, realized that this new alloy could be useful in watchmaking and published the first article on the subject. Upon reading about the material in March of 1897, Paul Perret contacted Guillaume requesting a sample. Guillaume constructed a balance spring from the new alloy and was “struck ill” at the results: The stiffness of the alloy increased with temperature, making the balance run faster. Perret suspected that a slightly different alloy would be perfectly stable in normal temperature ranges, eliminating the need to pair compensating springs and balances!

Perret immediately traveled to Paris to demonstrate his findings, and was amazed as Guillaume produced a plot showing the performance of every alloy. The two quickly secured the proper samples and traveled together back to Perret’s workshop in La Chaux-de-Fonds to construct and observe a prototype balance. Their progress was so impressive that it was shared by Dr. Hirsch, director of the Neuchâtel Observatory, in a June 17 meeting of the Society of Natural Sciences. On August 20, 1897, their nickel steel balance spring was recorded maintaining the same accuracy at 0 and 30 degrees Celsius. Uninterested in commercial matters, Guillaume returned to Sèvres, leaving Perret to bring the new material to market.

Paul Perret had already filed for a patent on the concept, registering it as number CH14270 on May 6, 1897. This patent covered the use of a nickel and steel alloy that increased in elastic force as temperature increased to compensate for a conventional “non-compensated” balance wheel. Incredibly, he had already determined appropriate ratios for a brass balance (28% nickel), a popular brass alloy (35%-36% nickel), and a steel balance (27% nickel). This was written and filed even before his hands-on demonstrations with Guillaume.

Perret’s next challenge was to improve the durability of the alloy. As was then done with steel springs, Perret applied a process of heat treating to harden the new material. This allowed it to be shaped and adjusted like steel, though the long-term reliability of Invar springs would continue to be a question for years to come.

The new spring material was dubbed Invar by Professor Marc Thury, reflecting its invariability to changes in temperature and magnetism. The self-taught Thury was well-known for his work on pendulum clocks and used Guillaume’s alloy to construct a remarkably accurate example. Invar remains a popular pendulum material to this day since it maintains its length as temperature changes.

But Paul Perret’s balance springs actively exploited the predictable expansion of slightly different Invar alloys. This discovery came at exactly the right moment, as the Swiss watchmaking industry was struggling to respond to the newly-formed balance spring cartel. On May 11, 1898, representatives from nearly every watchmaking company gathered in La Chaux-de-Fonds to discuss the creation of their own balance spring company to break the cartel. Although some of those in the audience likely still held a grudge against him, the hosts agreed to allow Paul Perret to take the stage.

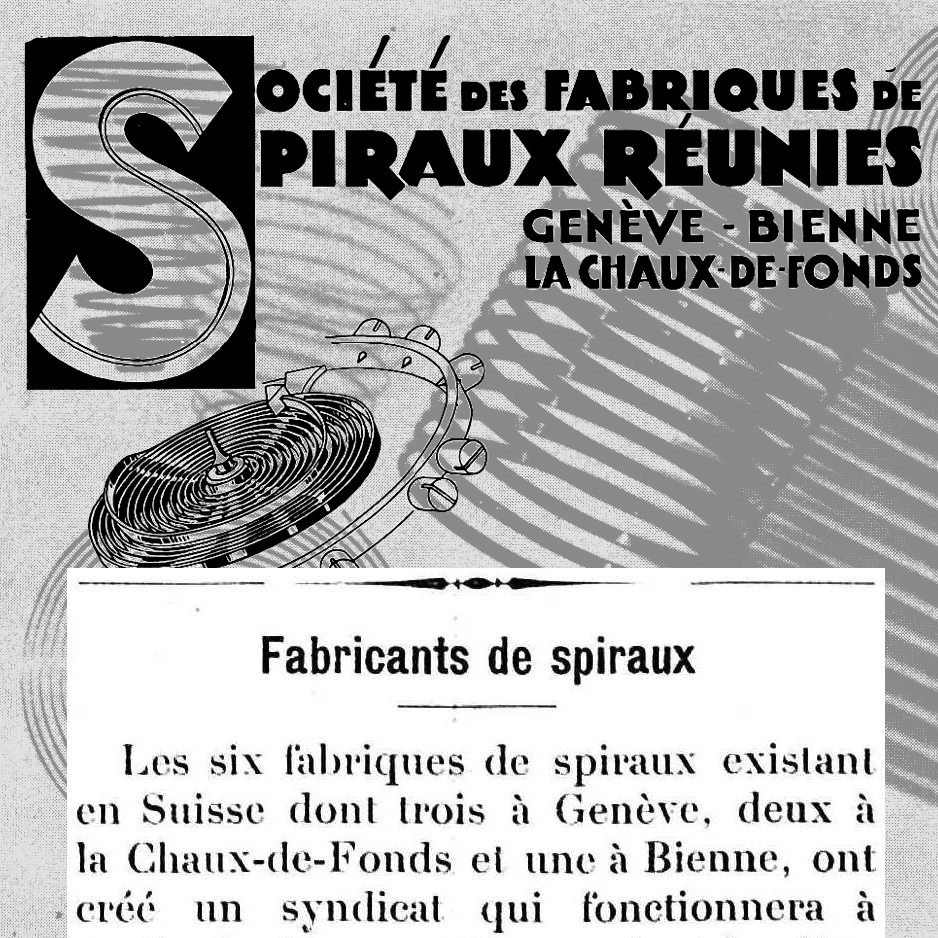

At the convocation of watchmakers, and in the watchmaking press the following day, Paul Perret detailed the remarkable properties of Invar balance springs and announced the creation of a new company to produce them in volume. Perret’s claims were supported by respected members of the watchmaking elite: Paul-David Nardin and Paul Ditisheim had experimented with Invar balance wheels and confirmed the material’s properties, while Dr. Hirsch of the Neuchâtel Observatory and Guillaume himself vouched for his experiments. Perret was able to convince the attendees that Invar balance springs could not only replace the steel springs of the cartel but could also enable simple balance wheels to achieve chronometer-level performance. But the meeting also resulted in a commitment to create the Société Suisse des Spiraux, a factory to produce conventional steel springs.

Perret went further than simply announcing the properties of Invar springs that day: He also detailed pricing and immediate commercial availability of two varieties! Although he struggled to produce them in volume, Perret was able to deliver some Invar springs from a workshop he set up in Fleurier by August of that year.

It seems curious that Paul Perret located his Invar spring factory in Fleurier rather than La Chaux-de-Fonds. A fairly small village, Fleurier is strategically located near the center of Swiss watch production and already housed many makers of watch components. And it was the home town of Charles-Édouard Guillaume, which was certainly also a factor. On August 1, 1901, the Fabrique de Spiraux Paul Perret was officially registered, though it had been in operation for three years in a smaller temporary space.

Perret immediately faced financial and health issues and declared bankruptcy on May 16, 1902. Like Guillaume, he struggled with inconsistent quality of the alloy produced by the Imphy forges. And even after tempering his Invar springs were easily damaged with improper handling. Although his Campyloscope made it easier to shape springs with precision, it was difficult to find workers in the small town of Fleurier. Most of the positions were eventually filled by young ladies rather than graduates of the Fleurier watchmaking school.

Paul Perret’s Death and Legacy

Despite being just 49 years of age, Paul Perret suffered a sudden illness on March 30, 1904. He was transferred to the hospital in Le Landeron but died that evening. The company was inherited by his daughter Emma and her stepmother Amélie (née Perrenoud). Emma handled the estate and issued a public appeal to continue the firm “in the interest of the many consumers of this product.”

Although information about these women is sparse, Emma appears to have been a capable businesswoman and accountant, managing the Busga watch factory in La Chaux-de-Fonds in the 1930s. She appears to have married a Mr. Juvet and lived in Geneva for a time. Emma’s sister Marie-Lucie was born in 1882 and likely died around 1893. We know nothing of their mother, Paul Perret’s first wife, but she likely died around the same time. Paul’s father Numa Perret also died that year, suggesting that an illness affected the family.

Paul Perret remarried around 1894. Amélie Perrenoud (1858?-1931) was well-connected in the watchmaking world: She was the aunt of Camille Flotron, a rising star in the world of watchmaking. He managed the main spring factory Resist SA before becoming president of UBAH (overseeing all component makers) and representing spring makers on the board of ASUAG. Amélie died on November 4, 1931, with Emma as Paul Perret’s only surviving family. Her prominent nephew was killed when his car was hit by a train in 1941. Sitting next to Camille Flotron in that car was Robert Guye, manager of the watch balance cartel.

Henri Wittwer, director of the Suchard chocolate factory and Jura-Neuchatelois railroad, and watch tool maker Edouard Ledermann purchased Perret’s Fabrique de Spiraux in 1904, while Perret’s assistant Albert Welter became manager. Wittwer and Ledermann partnered with the rebel balance spring maker Fabrique Nationale de Spiraux, angering the FSR cartel which was eager to produce Invar springs of their own. Paul Baehni of Bienne, director of the largest factory within the cartel, saw the potential of the alloy and pressed to acquire the company. Finally, on September 12, 1906, the cartel took over Paul Perret’s spring factory and acquired his patents.

Production of the springs was transferred to Baehni’s factory in Bienne and the newly-built FSR factory in Geneva in 1915. Perret’s Fleurier factory was closed and his roster of young female workers left unemployed.

Image: Apple Maps

Forgetting Paul Perret

It is obvious that Paul Perret still had detractors working against him during the final years of his life. The attributes of Invar were widely and publicly disputed by adjusters, who were certainly worried about losing their livelihood. Although Dr. Hirsch of the Neuchâtel Observatory was a supporter of Perret, his institution took its time in certifying the performance of his balance springs. And the industry backed the conventional steel springs produced by the Société Suisse des Spiraux and rebel factories rather than throwing their weight behind Perret’s Invar springs.

But his sudden death changed everything.

The reputation of Invar balance springs as temperamental and unproven was quickly rehabilitated by the cartel. FSR pushed to release a study confirming the remarkable properties of Invar springs, conducted by Dr. Arndt of the Neuchâtel Observatory. The great Longines factory in Saint-Imier became an enthusiastic supporter of Invar springs, celebrating the accuracy of their mass-produced watches. Soon Invar balance springs became the standard for firms like Moeris (known for anti-magnetic watches), Omega, Zénith, and Tavannes.

For a few years, the name of Paul Perret was generally respected in the industry. His Invar springs enabled watchmakers to industrialize, since they no longer needed to rely on skilled adjusters and compensators. And their performance boosted sales.

But the Invar alloy was constantly being improved, and Perret’s contributions were forgotten. Guillaume created new alloys, including Elinvar in 1920, and he became a genuine celebrity when he received the Nobel Prize that year. Guillaume’s name had far more value than Perret’s. Although Guillaume was personally inclined to share credit with his collaborator even late in life, Perret’s name gradually disappeared. His contribution was largely left out of Guillaume’s obituaries when he died in 1938. Today Paul Perret is hardly ever mentioned, though a homage watch brand did briefly use his name from 2014 to 2020.

The largest watchmakers learned to appreciate the FSR cartel after World War I as industry consolidation became widely accepted. The FSR was absorbed into ASUAG in 1932 along with most of the rebel balance spring makers. An even better balance spring material was developed by Reinhard Straumann just a few years later, and most watchmakers soon switched to his Nivarox alloy, which was also produced by the cartel. Yet Invar remains in wide use today, and every Jaeger-LeCoultre Atmos clock features an Elinvar torsion spring.

The Grail Watch Perspective: We Should Celebrate Paul Perret

Few individuals contributed as much to watchmaking as Paul Perret, yet he is largely forgotten today. Whether for his adjusting and spring shaping machines, his promotion and exploitation of the patent system, or his contribution to the development of a temperature compensating balance spring, Paul Perret left a lasting legacy. And the way he and his friends promoted his accomplishments is just as compelling. If he had not died so suddenly and at such a young age, perhaps there would be even more to tell. But all of this is enough: Paul Perret should not be forgotten!

Reference Material

Happily, I am not the only person to note the accomplishments of Paul Perret. I must first give credit to Hans Weil of Faszination Uhrwerk who created a remarkable study of Daniel JeanRichard, Pierre-Louis Guinand, and Paul Perret. This document (in German), provides much-needed context and helps fill in the story of Paul Jeannot as well! I also recommend Andreas Kelz’ excellent article, Paul Perret and the Swiss Patent No. 1.

I have a great deal more I could say about Paul Perret, and certainly gave short shrift to his other patents and inventions. I also have much more to say about Paul Berner, Marc Thury, Camille Flotron, Adolphe Hirsch, and many other supporting players in this story. Hopefully I will have the time to share their stories as well!

Because information on Paul Perret is so scarce, I am sure I have made some mistakes in this article. If you have additional material or clarifications, please email me (Stephen at grail-watch.com) and I will update this piece. I would particularly love to add a picture of Paul Perret himself, additional details on the life of his daughter Emma, and more about his other accomplishments.

- The Swiss Patent System

- The Talantoscope

- Guillaume and Perret

- Paul Perret’s Family

- Paul Perret’s Obituaries

The Swiss Patent System

Paul Perret was elected to the Société d’Emulation Industrielle in La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1881 and promptly directed the organization to support the establishment of a patent system in Switzerland. This was an unusual move, since the society had previously steered clear of politics. But when the national council rejected a bill to establish the system, individuals like Perret supported referenda to establish such a system directly. The initial referendum on July 30, 1882, failed but Perret convened a meeting in Olten in October to continue the campaign. The system was ultimately established in November 1888, and Perret received the first patent!

July 1882 Referendum

Patents (REVISION OF ART. 64.)

The Industrial Emulation Society of La Chaux-de-Fonds to the federal electors of the canton of Neuchâtel.

Dear fellow citizens!

The Swiss people are called upon to decide on July 30 an addition to the Federal Constitution, stolen by the Chambers, and intended to give the Confederation the competence necessary to legislate on the protection of inventions in the field of industry and agriculture, as well as on the protection of designs.

For the first time, the Industrial Emulation Society intervenes in a popular vote: That is to say that it is not a political question. We are indeed in the presence of a purely economic and industrial question whose solution will cost nothing to the State and will contribute to the prosperity of the nation.

We come to urge our fellow citizens to vote for the new constitutional provision submitted to them and to set out the main reasons that guide us:

1. Until now, intellectual property has not enjoyed any protection with us. The most important discoveries and inventions can be exploited by anyone, overnight, without there being any guarantee for the work, always considerable and often ruinous, to which the inventors have devoted themselves. Why has the Law, so concerned with the protection of all other property, whatever its origins, remained indifferent to that of inventions? It will be difficult to say, but what is certain is that this unequal treatment constitutes an injustice which must disappear.

2. The Federal Constitution provides for the protection of literary and artistic property. A law on this matter is currently before the Chambers. Why should industry not have the same right? Why should the worker not enjoy the same advantages as the writer, the painter, the sculptor, etc.?

3. If we want to see our watchmaking schools, our art schools, and all the institutions whose goal is the technical and artistic development of work prosper, those who make the necessary sacrifices to follow these courses must know that they do not run the risk of being dispossessed of the fruit of their labors.

4. All civilized nations protect inventions and most of them work together for the creation of international legislation in this field. A draft convention drawn up by representatives of thirteen States provides for the creation of a central office for patents of invention, of which Switzerland would have the honor of being the seat.

5. The absence of a protective law, in our country, has already had unfortunate consequences for us, because it has led a good number of Swiss to seek – with regret – outside the homeland, the guarantee that it will not offered them point; it forced them to carry abroad the product of their labor and their intelligence and thus to join foreign competition.

6. Vis-à-vis other nations, our situation becomes more false day by day. Here, as a result of a commercial treaty, foreigners enjoy with us a protection which does not exist for the Swiss. There, the law only protects nationals of countries in which reciprocity exists. Everywhere we are bound in a state of suspicion which comes to light in all the exhibitions, as if we were a nation which relies on counterfeiting to live, whereas free Switzerland must be enlightened enough to know that there is no lasting prosperity than that which is based on the loyalty of all its children.

Dear fellow citizens!

Our canton cannot remain indifferent.

Our industrial interests require us to turn out en masse at the polls to show that we are interested to a large extent in this important question. An imposing demonstration will give us a good situation to make our wishes heard during the elaboration of the federal law which will be failed following the revision of the Constitution.

So let’s all go to the polls next Sunday and vote: YES!

Chaux-de-Fonds, July 27, 1882.

In the name of the industrial emulation society gathered in assembly today: THE COMMITTEE: Paul Perret, President; Auguste Ducommun, Vice-President; Edward Steiner, Secretary; Jules Brandt, Deputy Secretary; Edward Meyer, treasurer; Charles Couleru-Meuri, Deputy Secretary. Fritz Humbert, Eugène Lenz, Nutin Fiffel, Auguste Reymond, Clément Guisan, Tissot-Vougeux, Jean Brandli, Auguste Klinger, Philippe Girard, Henry Perregaux, Albert Vuille, Eugene Soguel, Fritz Cuanillon, Albert Sandoz.

l’Impartial, July 29, 1882

October 1882 Olten Meeting

The issue of patents, so unfortunately rejected by the people on July 30, will be taken up again. We know that the Industrial Emulation Society of La Chaux-de-Fonds requested this, in order to have a point of support in order to organize the petitioning of the federal authorities for the main Swiss companies which are interested to trade and industry. The Committee, encouraged by the favorable and benevolent replies which it has received from various quarters, has taken the initiative of convening in Olten, on Sunday, October 8, a meeting of delegates from these societies. The appeal is at the same time addressed to the press and to all those who have the protection of inventions at heart. Here is the text of this document:

Dear fellow citizens, dear Confederates,

The result of the July 30 referendum concerning the protection of inventions in the field of industry and agriculture, as well as the protection of designs and models, caused throughout Switzerland such a general feeling of astonishment that it is permissible to think that this vote does not represent the last word of the nation.

The many supporters of this protection did not think for a moment that one could offend cantonal sovereignty by giving the federal power this administrative power, because it is obvious that the cantons would be powerless to exercise it, and they believed that the triumph of their idea was assured.

Hence an almost complete absence of work to overcome the indifference of the electorate and to enlighten the vote.

The undersigned committees, while expressing their respect for any demonstration of universal suffrage, whatever the result, cannot however resolve to consider the question as definitively settled.

They have the deep conviction that concerns unrelated to the thing itself exerted a great influence on the vote.

They hope that by calling from the misinformed people to the well-informed people, our homeland can finally be provided with an institution necessary for our industrial and economic development.

It is guided by this idea that the undersigned committees, thinking that it is necessary to act while public opinion is still awake, believe that they must, as a first step, appeal to all the companies which interests of commerce and industry, to the press and to all persons interested in the protection of inventions, and to invite them to attend a General Assembly which will take place at the Buffet de la Gare d’Olten, on Sunday October 8, 1882; at 11.30 a.m., with the following agenda. Is there any reason to take up again the question of patents for invention now, and, if so, what is the best course of action to obtain a favorable result?

This appeal is addressed to all the societies and to all the newspapers of which we have been able to obtain the list. It is certain that we will have made involuntary omissions, so we ask all newspapers sympathetic to the work to reproduce it, so that all interested societies know that they are warmly invited to attend the meeting in Olten.

Dear fellow citizens, dear Confederates,

We are counting on the support of all men who are concerned about the future of our country and who want to contribute to ensuring this future through innovation based on principles of justice and loyalty in work, the value of which cannot be contested and which all civilized nations have enshrined in their laws.

We believe that the federal authorities, who have pronounced themselves by a large majority in favor of this new constitutional provision, will not hesitate to adopt it, if the Swiss people express their wish by imposing demonstrations.

This is why we address an urgent appeal to all those who agree with us that we must act. The indifference that accompanied the popular vote will be without excuse today, after the lesson of July 30th.

So come in large numbers to Olten, so that when we leave the assembly we can all cry out together: The invention patent is dead; long live the patent!

September 1882.

On behalf of the Committee of the Industrial Emulation Society: President, Paul Perret; Secretary, E. Steiner. On behalf of the Assembly of Sculptors of the Öberland Sculpture Institute and the Society of Sculptors of Bronze: President due filled, H. Baumgartner, pastor; Secretary, C. Bigler-Leitz. On behalf of the Commission of the Society of Former Polytechnicians for the adoption of the protection of inventions: President, P.-E. Huber; Secretary, H. Paul, Engineer. On behalf of the Intercantonal Society of

l’Impartial, October 1, 1882

Industries of the Jura: President, H. Etienne; Vice-President, E. Francillon. On behalf of the Swiss Section of the International Permanent Commission for the Protection of Industrial Intellectual Property: President, J. Weibel; Secretary, E. Imer-Schneider, Engineer. On behalf of the Geneva Commercial and Industrial Association: Chairman, E. Pictet; Vice-President, J. Weibel.

The Olten Meeting, convened on Sunday, 8 October, had 70 delegates from various Swiss companies involved in industry and commerce. Mr. Paul Perret, President of the Industrial Emulation Society of La Chaux-de-Fonds, opened the meeting with a speech included in the protocol and which will be communicated to the Swiss press.

The office of the assembly was composed as follows: MM. Hoffmann-Merian, Basel, President; Paul Perret, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Vice-President; D’Oelli, Berne, German Secretary; Humbert-Droz, Locle, French secretary; Mulhaupt, Berne, and L. Rozat, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Scrutineers.

Several speakers developed the question of industrial protection and declared themselves in favor of patents. This question must be taken up again despite the disastrous result of the popular vote of July 30th. M. Paru, Chancellor of the State of Geneva, spoke in this sense; Emile Merz, engineer in Basel; Zschokke, deputy to the State, at Aarau, and Greisely, at Solothurn.

Mr. Steiger, from Hérisau, a very determined adversary, proposes not to take up the question again. The assembly, unanimously minus two votes, decides that it will be resumed immediately.

The program proposed by the Industrial Emulation Society of La Chaux-de-Fonds was adopted in full and almost unanimously.

The office of the Intercantonal Society of Jura Industries is appointed central committee; he will designate two committees of action and execution, one for German Switzerland, the other for French Switzerland. This mode of proceeding was very favorably received by the assembly, which augurs well for the upcoming campaign. The Central Committee, inspired by the ideas expressed in the meeting of October 8, will bring it to a successful conclusion.

Many testimonials of congratulations and energetic support reached the Initiative Committee from the invited companies who could not be represented.

Everything leads us to believe that the desired end will be achieved for the greater good of our national industries.

l’Impartial, October 11, 1882

The First Swiss Patents

Although Perret’s referenda failed, a system of patents was ultimately established in Switzerland in 1888. Perret, being the driver of this reform and a very prolific inventor, arrived the night before to register the very first Swiss patent on November 15, 1888. He also received four more patents that first day!

Patents of invention, literary property, etc. Bern, October 6, 1888.

In the legal referendum period that ended on the 2nd, no opposition was raised against the Federal Law on Invention Patents of June 29, 1888.

The Federal Council ordered the publication of this law in the official collection and approved its implementation from November 15.

At the same time, it decided that, under the name of the Federal Intellectual Property Office, a special division of the respective federal department (under that of foreign affairs) would be created, which will be responsible for the enforcement of the following laws: a) The Federal Law on Invention Patents; b) The Federal Law concerning the protection of trademarks; c) The Federal Law on literary and artistic property; d) The federal law – currently in deliberation – of designs.

The belongings to this office will be sent, for the time being, by the following staff: A director, one or two assistants, a manager and the necessary number of clerks.

The Department of Foreign Affairs is responsible for contesting these various functions. Upon appointment to these positions, the Federal Council will fix the treatments for them according to the Federal Law on the Organization of the Federal Department of Commerce and Agriculture of April 21, 1883, and will ask this effort for the necessary appropriations from the Federal Assembly.

l’Impartial, October 9, 1888

The Swiss law on patents will enter into force on November 15th. The question has been on the table for a long time, says M. C. Bodenheimer, in the Lausanne Gazette, where he devotes the following lines to this question:

As early as 1849 a motion requesting the introduction of patents was presented to the National Council, which rejected it. In 1851, petitions to the same effect from Mr. Theodore Zappinger, of Mannedorf, and two other Zurich manufacturers. In 1834, petition from M. Lambelet, from Verrières, former member of the National Council; the National Council also rejects it. In 1861, the Prussian legation to the Swiss Confederation requested the Federal Council to provide it with information on the effects produced in Switzerland by the absence of any protection for inventions; the Federal Council replies by transmitting to La Prasse an opinion from MM. Bolley and Kronauer, professors at Zurich, the former of chemistry, the latter of mechanical technology, and both speaking out against patents. In 1862, the National Council rejects a motion of Dr. J. Schneider, of Bern, asking for the introduction of patents.

In 1865, the same fate befell the petition of Mr. Walter Zappinger, chief engineer of the firm of Escher, Wyss and Co., and yet this petition was supported by Alfred Escher, Dubs, Rüttimann, Vigier, Eugene Escher, & Co. The same year a brochure was created by Dr. Honegger for patents. In 1869, a pamphlet by Mr. Victor Boeehmert, professor at the Polytechnic (today director of the statistical office of the kingdom of Saxony) against patents. In 1871, rejection of a motion by Dr. Joos, asking that an article be introduced into the Constitution allowing the Confederation to legislate without patents. In 1874, favorable brochure by Mr. Adolphe Olt. The same year, rejection of a new Zuppinger petition. In 1876, petition of MM. Nestlé et al., petition by 43 Swiss photographers and to the National Council, motion by MM. Bally et al. In 1877, favorable pamphlet by Max Wirth, former director of the Federal Bureau of Statistics. The same year the committee of the Swiss Society of Commerce and Industry (the president then being Mr. Kochlin-Geigy, from Basle) decides on various questions relating to industrial and literary property that the Federal Department of Commerce had submitted, and requests, with regard to patents, that the Saisse not take a decision before Germany has legislated on the matter.The question finally took shape after Mr. N. Droz, then head of the Federal Department for the Interior, had published a study on the question of patents entitled “general inquiry and preliminary draft law”.

As early as 1873 the Federal Council was represented at Vienna, where the Universal Exhibition was linked to the International Congress of Industrial Property. In 1878, a second congress was held in Paris, also on the occasion of the exhibition. The Federal Council delegated the author of these lines, Mr. Imer-Schneider, a civil engineer, and Mr. Schreyer, now an insurance director and at that time a professor in Geneva. The report, which we sent to the Federal Council on our return from Paris, is now just ten years old (October 1878). In his conclusions he said among other things: “… A very striking reproach that we heard made selling the congress to the Swiss industry in its present position, that is to say in the absence of patents of invention is that of not having perfected the foreign inventions which it appropriated, and on the contrary of having made only mediocre imitations of them. This observation, if it is justified, is important, because it refutes one of the main arguments of the adversaries of the protection of inventions, who see in this very protection an obstacle to the general progress of the industry, which would result. This means that, during a certain period of time, the inventor alone has the right to perfect his invention … The Swiss will not be able to rely on protecting industrial property for a long time … It owes this, among other things, to the reputation of its industry. At the congress, an official delegate from America, Mr. PolIok, called Switzerland a country of counterfeiters. We have rejected this unfair reproach, but there will not be, each time this reproach is peddled by interested competitors, we will be present to respond.”

After pointing out that watchmaking, embroidery and other industries could not do without industrial protection if foreigners do not want to exploit their reputation for their own profit, we added: “There is also another point; it is that of the internal discipline of our industries. Germany has entered into the path of minute protection, and at Congress she has supported the projects of international understanding. (She has since abandoned them. The author.) And why? Is it not up to a certain point because the German industry is impatient to be able to get rid of this epithet “schlecht und billig” (bad and cheap) that M. Reuleaux (he was a delegate to the congress) act has applied and which has earned him such enemy numbers and such warm friends? And don’t we in Switzerland have some considerations of this nature to weigh and examine?”

“Once again we ask what would be the role played by Switzerland if it remained isolated in the midst of the international understanding which is in the process of being created? Forced by treaties to protect foreigners, it would be powerless to protect its own nationals.”

Since then, international agreement has been reached and Switzerland has adopted its own law on patents. At the time when it will come into force it was perhaps worth remembering that we have been asking for it for a long time.

l’Impartial, October 20, 1888

Under this title we will regularly publish the list of registered patents concerning the watch industry. We recall, in passing, that the federal office of intellectual property opened, in Bern, on November 15, 1888, rue de la Lorraine, n° 3 (asylum for the blind); those interested may obtain free of charge from the said office copies of the laws, regulations and federal decrees on the subject, as well as forms for applications for patents of invention and certificates of temporary protection at exhibitions. These same forms will continue to be delivered free of charge to those concerned by the care of the cantonal chancelleries.

It should also be remembered that the Federal Trademark Office is also transferred to the above address.

From the first day of opening of the office on intellectual property, 120 applications are received: here are those for patents concerning the world of watchmaking:

N° 1. 15 nov. 1888, 8 h. – Perfectionnements apportés à la construction des mouvements de montres de toutes dimensions. – Perret, Paul, rue du Pare, 65, Chaux-de-Fonds.

N° 8. 15 nov. 1888, 8 h. – Nouveau mécanisme de remontoir et de mise à l’heure par le pendant pour montres de tous calibres. – Kuhn & Tieche, fabricants d’horlogerie, Bienne.

N° 9. 15 nov. 1888, 8 h. – Nouveau système de montre, grande sonnerie, répétition. – Heuer, Edouard, Bienne.

N° 10. 15 nor. 1888, 8 h. – Nouvelle disposition du mécanisme des montres à répétition avec chronographe. – Goy-Golay, Auguste, Brassus (Vaud).

N° 12. 15 nov. 1888, 8 h. – Nouveau système de chronographe-compteur. – Boret, Hermann, Quartier neuf, Bienne.

N° 15. 15 nov. 1888, 8 h. – Nouveau calibre de montres de poche pour être exécuté en toutes dimensions et en tous métaux. – Humbert fils, Charles, successeur, Chaux-de-Fonds, rue Léopold Robert, 03.

N° 21. 15 nov. 1888, 8 h. – Nouveau système de raquette avec colimaçon régulateur. – Perret, Paul, rue du Parc, 65, Chaux-de-Fonds.

Nº 22. 15 nov. 1888, 8 h. – Pièces détachées servant à fabriquer par un nouveau procédé les balanciers compensés et spiraux pour montres et chronomètres. – Perret, Paul, rue du Parc, 65, Chaux-de-Fonds.

N° 23. 15 nov. 1888, 8 h. – Perfectionnements apportés à la construction du moteur (ressort et barillet) des montres de poche de tous systèmes et de toutes dimensions. – Perret, Paul, rue du Parc, 65, Chaux-de-Fonds.

N° 21. 15 nov. 1888, 8 h. – Perfectionnements apportés à la construction des couronnes de remontoir pour montres de toutes dimensions. – Perret, Paul, rue du Parc, 65, Chaux-de-Fonds.

N° 32. 15 nov. 1888, 9¼ h. – Nouvelle montre chronographe. – Jacot-Burmann, Bienne, et Æby, Léo, Madretsch.

N° 44. 15 nov. 1888, h h. – Nouveau système de ferrure à glace. – Perret, David, Neuchâtel.

N° 46. 15 nov. 1888, 8 h. – Nouvelle composition des plaques métalliques servant â la fabrication des boites de montres, médaillons et autres bijoux. – Bargel, François, place Cornavin, Genève.

l’Impartial, December 6, 1888

The Talantoscope

Paul Perret was said to have invented his adjusting machine as early as 1873 (when he was just 19 years of age) and certainly perfected it by 1877 when he published the following article in Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie. Later versions were named Talantoscope and were produced for commercial sale by 1883.

The Talantoscope Controversy

A controversy over the device arose in 1889 when it was suggested that the machine produced such good results that skilled adjusters were no longer needed. Not wanting to fan the flames, Perret ignored the talk and this caused rumors that he meant to sell the device in America rather than in Switzerland.

We are asked for the hospitality of our columns for the following lines:

A very important invention was made by M. Paul Perret, of La Chaux-de-Fonds, concerning the adjustment of watches.

The inventor communicated to a group of competent men, the results at which he arrived, and it is these people who take pleasure in making public the merits of Mr. Paul Perret.

In their opinion, this invention will mark an important date in the history of watchmaking and its author will henceforth be among the boldest innovators in this industry.

Performing precision adjustment mechanically and in an absolutely scientific manner, then applying it to inexpensive watches, such is the problem posed by Mr. Paul Perret in 1875, and which will seem insane to the eyes especially of those who deal precision adjustment.

After 14 years of study, research and application, our compatriot has carried out this vast project. He had to overcome one after another considerable difficulties, difficulties that several masters of science had declared insurmountable.

The invention of Mr. Paul Perret currently remains a secret but we were allowed to attend an experiment made especially with a view to proving the existence of this invention. The Geneva Observatory was kind enough to lend its support to this scientific test. Twenty-four balance cocks and pendulums belonging to movements he did not know were given to Mr. Paul Perret and at the end of the same day, he returned the adjustments made.

At that time only the cogs and pendulums were adjusted to the movements and these were carried directly without prior observation at the Geneva Observatory. The observations lasted twelve days namely during top, right, left, dial bottom, top, cooler and oven with intermediate days and to finish during top.

As these movements were of standard quality, two could not subsequently withstand the test of stops resulting from manufacturing defects. Of the 22 who remained under observation, twenty-one fulfilled the conditions for the 1st class bulletin (Category A of the Geneva Observatory); Only one gasped for a 3 second gap.

Citation of these results is sufficient. Any comment becomes useless, if one takes into account the fact that Mr. Paul Perret, born near La Sagne in 1855, was a farmer until the age of 17 and prevented from regularly attending a local school, one must be surprised at the perseverance he had to display to walk so quickly and get so far. Indeed, he settled in La Chaux-de-Fonds as an apprentice watchmaker in 1872, and already in 1873 he invented his first adjusting machine. In 1874 he was called as technical director of the Fontainemelon blanks factory, functions which he resigned in 1876 to devote himself to the practice of watchmaking and to continue his studies concerning the problem he had posed in 1875. In 1878 Mr. Paul Perret exhibited in Paris two machines of his invention, the Talantoscope and the Campyloscope, which earned him a medal and the praise of the jury.

In 1881, at the national watchmaking exhibition in La Chaux-de-Fonds, we see him obtain the first class prize with silver medal, the highest award, and in 1883 we meet him in Zurich as a member of the jury of the Swiss national exhibition.

In 1882, it was Mr. Paul Perret who took the initiative in the campaign which fortunately endowed Switzerland with a law on patents for invention and from 1878 to 1888 he delivered 200,000 Breguet settings to industry. Despite all these occupations, Mr. Perret nevertheless continued unceasingly to pursue the goal he had proposed and it is thanks to this incessant work that he arrived at the full possession of his invention.

Also to this brave pioneer of our national industry we say courage! To the work belongs the reward.

l’Impartial, June 28, 1889

We receive the following letter for which we are asked for a place in our columns:

Mr. Editor of the Impartial, your issue the day before yesterday contains an anonymous article about Mr. Paul Perret’s wonderful inventions.

It seems to me that the people who wrote this statement would have done well to sign their article so that it does not look like a large American advertisement.

If after fourteen years of research and application, the inventor of the Talantoscope and the Campyloscope “carried out a vast project for for which he had to overcome one after the other considerable difficulties, difficulties that several masters of science had declared insurmountable!”

If really our young compatriot from the surroundings of la Sagne made a discovery that places him at the rank of famous men, it is an insult to him to give in a newspaper, under the veil of the anonymous, an overview of his invention and his biography.

While thanking you in advance, please accept, Mr. Editor, my most respectful greetings.

A. S.

l’Impartial, June 30, 1889

We published, in our Friday edition, a communication relating to an alleged invention of Mr. Paul Perret, concerning the setting of watches. We accorded hospitality to these lines for the reason above all that the said communication was addressed to other Neuchâtel and even Geneva newspapers; several of them – the Neuchatelois and the Tribune de Genève in the lead – have published this article. We have also inserted it in our columns with the aim of provoking a public debate on the alleged inventions of Mr. Perret which have been talked about for some time.

We have already received a communication that we published in a previous issue. Today we receive the following letters to which we grant the hospitality requested by their authors:

La Chaux-de-Fonds, July 1, 1889.

Mr. Editor of the Impartial, You would oblige me, by inserting in your honorable journal the following lines:

I have just read in l’Impartial of June 28, an article pompously praising an invention of Mr. Paul Perret, adjuster in La Chaux-de-Fonds, an invention by means of which he claims to be able to adjust watches in the different positions without the help of movements. I am certain that this is not possible, for the most perfect machine cannot take into account the irregularities resulting from the driving force, the train, the assortment, the crashing of the escapement, the friction of pivots in the stone holes.

How could a machine predict and correct these irregularities? Irregularities which, as all competent persons know, vary from one watch to another.

I doubt very much that the competent people mentioned in the article in question are Nardins, Potters, Borgsteits, etc., etc.

How is it that the Geneva Observatory granted Mr. P. P. 1st class bulletins (Category A), when its regulations provide for 45 days of observation?

Please accept, Mr. Editor, with my thanks in advance, the assurance of my highest consideration.

N. ROBERT-WÆLTI.

Mr. Editor of the Impartial, please grant these few lines the hospitality of your columns:

In No. 2619 of l’Impartial, published Friday, June 28, I read an anonymous article relating to inventions and other specialties of P. Perret.

Allow me to point out to you that this article is only a tissue of erroneous affirmations and that it seems very much to be the work of a charlatan.

Then, from information taken from a good source, I am permitted to say that it is completely inaccurate that Mr. P. Perret obtained 1st class bulletins (Category A) at the Geneva Observatory.

To obtain these certifications, the parts must undergo 45 days of tests; however, Mr. Perret’s watches having only stayed 17 days at the Observatory, no certificate could therefore be delivered to him.

As for the amazing result, here it is: After 17 days of observations, 17 parts out of the 24 in question had already failed and the remaining 7 would certainly have suffered the same fate if the tests had continued during the 45 regulatory days.

For the moment, I will not point out the other errors with which the authors of this article have been pleased to point out our valiant pioneer, the conqueror of the considerable difficulties which several masters of science had declared insurmountable.

Please accept, Mr. Editor, with my thanks in advance, assurance of my perfect time.

G.-R.

On the other hand, the Geneva Observatory sends the following correction to the Tribune:

The tests undergone by watches registered to examine the results of Mr. P. Perret’s invention for adjustment cannot be assimilated to the regulatory tests required for category chronometers.

It cannot therefore be claimed that the majority of these pieces would have obtained a very satisfactory report, as defined by the rules of the Observatory. We can only affirm that seven of the watches compared over 17 days provided average deviations remaining below the limits assigned for obtaining these ratings.

You will find on the advertisement pages of this issue a humorous article with the title: Extraordinary progress, which naturally targets Mr. Perret and his invention. It will be curious to see how he will defend himself against the assertions contained in the above letters.

l’Impartial, July 1, 1889

Extraordinary progress!

A young compatriot, having arrived after eighty-five years of study at the goal of his research concerning a machine to adjust chronometers automatically, recommends himself to the industrialists of La Chaux-de-Fonds and the surrounding area.

With the help of this machine, it can provide after 12 hours two large chronometer settings, with first-class Observatory bulletins, observed in 36 positions, guaranteed to be set to 2 hundredths of a second.

The undersigned declares that, if a single piece from this house fails, he will not be compensated.

To execute these adjustments, it is enough to send the numbers of the cartons and the screw of a cock.

Campi LOOS,

Rue des Talents N° 100 (Oscop house), SAINT-IMIER.

N.B. This invention is for sale at the price of TWO million and 25 cents.

l’Impartial, July 1, 1889

We receive the following letter to which we grant the hospitality of our columns in the same way as to the communications dealing with the same subject, and which have been inserted in our journal.

Geneva, July 5, 1889. Mr. Impartial Editor, La Chaux-de-Fonds.

We take advantage of the kind hospitality you accord to the articles concerning the inventions of Mr. Paul Perret.

First of all, we claim the authorship of the very first article, which highlighted the merits of Mr. Paul Perret and the path he has traveled so quickly.

Acting on behalf of a few friends, we wanted to encourage the inventor and do him justice, breaking with the tradition that often wanted the researcher in Switzerland to remain anonymous and even sometimes frustrated of the benefits of his painful work.

We recognize that the discoveries of Mr. Paul Perret can arouse great emotion. Our friends and ourselves could hardly believe them when they were first developed among us, but we had to bow before the brutal fact.

We will not speak here of a first experiment which took place on movements provided by Mr. Paul Perret. It was on this occasion that, wanting to have absolutely conclusive proofs, we imposed on him the experiment in question and which consisted in providing the operator with 24 movements which would be absolutely foreign to him and of ordinary quality.

This is what happened last April and we certify that Mr. Perret only received the cogs and balance wheels for his adjustments and that he made them in a single day. We further certify that the cogs were adjusted to the movements under our eyes and that we transported them to the Geneva Observatory without any prior observation having taken place. The experiment made under these conditions was reckless; also what was the general astonishment when we received communication of the magnificent results obtained by these movements.

The table of these observations, issued by Colonel Gautier, director of the Geneva Observatory, is a very interesting document, which will be published in the August issue of the Journal suisse d’Horlogerie.

We refer our readers to it, while expressing the wish that Mr. Perret would add a few developments.

Receive, Mr. Editor, the assurance of our highest consideration.Albert-H. Potter, Berthold Pellaton

l’Impartial, July 7, 1889

Dear Editor of L’Impartial, at La Chaux-de-Fonds.

You published a press release from the Geneva Observatory about our first article on the inventions of Paul Perret.

After conferring with the Director of the Geneva Observatory, we recognize that the form of our assessment could mislead by suggesting that we wanted to assimilate 12-day tests with the regulatory 45-day tests imposed on Category A chronometers.

We only heard of the results obtained to compare them with the limits imposed on pieces of this category, results deduced from the TABLE below certified by the director of the observatory.

Receive, Sir, the assurance of our highest consideration.

Albert H. Potter, Berthold Pellaton

l’Impartial, July 12, 1889

We remember the controversy that arose, a year ago, after the announcement of results obtained by Mr. Paul Perret, of our city, for the adjustment of watches by a rapid process of his invention, and presented to the Geneva Observatory without the running and adjustment of these watches having been subjected to any prior observation.

The results were so surprising that many people had questioned them and taxed their publication as mere advertising. A circular which we have in front of us tells us that the house of Paul Jeannot, of Geneva, has acquired joint ownership of the inventions, models and trademarks of Mr. Perret and that it has founded, in our city, under his technical direction, a watchmaking factory, with application of its mechanical precision adjustment process.

At the same time, we learn that the important house of Paul Jeannot, from Geneva, will move its head office to La Chaux-de-Fonds next November.

l’Impartial, June 12, 1890

Guillaume and Perret

Paul Perret’s greatest accomplishment was the discovery, with Charles-Édouard Guillaume, of the nickel steel alloy known as Invar. Guillaume’s work showed the many properties of the alloy but it was Perret who developed the material for use as a balance spring for watches.

Paul Perret’s Announcement of Invar

The hairspring crisis

They write to us:

According to the scholarly research of Dr. Ch.-Ed. Guillaume on nickel steels, with his collaboration and that of the metallurgical company of Commentry-Fourchambault, I discovered a new principle, which allows this metal to be applied to the adjustment of watches.

Today, after carefully verified work, I am able to provide the watchmaking industry with two solutions: one which replaces the hardened steel hairspring with the steel-nickel durei hairspring; the other replacing the soft steel hairspring with another, also in nickel-steel, which is superior to it being not very magnetic and very little oxidable.

The hardened steel-nickel hairsprings, advantageously replacing the hardened steel hairspring, will be on sale from May 15. Those which will replace the soft steel hairspring from June 16.

Prices are set at:

Fr. 2.— a dozen for the dureis spirals, tight with turns, sizes 1 to 50, and spaced apart with turns, sizes 12 to 25.

Fr. 0.50 per dozen for soft, common sizes, from sizes 7, tee 1, to size 30.

I will deal exclusively with wholesale sales, the depositaries, whose names will be published soon, will have retail sales.

La Chaux-de-Fonds, May 10, 1898.

Paul PERRET

La Fédération Horlogère, May 12, 1898

Solution to the hairspring crisis

The watch manufacturers of La Chaux-de-Fonds, brought together here, numbering around a hundred, by the General Secretariat of the Cantonal Chamber of Commerce, were made aware of the question through a complete history accompanied by a presentation of the various solutions. Delegates from the Society of Watch Manufacturers of Le Locle, the Berne Cantonal Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the Union of Watch Manufacturers of the Canton of Bern were present.

Unanimously, the assembly refused to enter into discussion on the proposals for agreement offered by the Society of Reunited Spiral Factories.

A communication concerning the steel-nickel hairspring, which Mr. Paul Perret, from La Chaux-de-Fonds, will launch, was received with sympathy by the assembly.

Taught by experience, and determined not to suffer, in the present and in the future, the tyranny of any group of speculators or hoarders, the assembly decided the immediate creation of a joint stock company for the manufacture of hairsprings for watches.

Immediately, around thirty thousand francs were subscribed. At the time of writing, underwriting among manufacturers in La Chaux-de-Fonds exceeds 50,000 francs. Bienne supplies 16,000 francs. We will know, in a few days, the results of the other industrial centers.

These are the first fruits of the rise of April 0 and the intransigent attitude of the Society of United Spiral Factories.

La Fédération Horlogère, May 15, 1898

Nickel steels

There is a lot of talk at the moment about nickel steels, with regard to the appearance of Paul Perret hairsprings, made with metal of this composition. We therefore read with interest the following article, published in the Chronometric Review:

The Bulletin of the National Industry Encouragement Society contains in its March 1898 issue a memoir by M. Ch.-Ed. Guillaume, entitled Research on nickel steels, in which this scholar, member of the Institute, reports on the numerous tests he carried out on alloys obtained by adding varying amounts of nickel to steel.

Mr. Ed. Guillaume divides nickel steels into two distinct categories: steels containing 0 to 25% nickel and to which he gives the name of irreversible alloys and those where the nickel content exceeds 25% and which he calls reversible alloys because of their different magnetic properties.

Most nickel steels are not very oxidizable, they are all very tough, remarkably homogeneous and capable of a fine polish: reversible alloys lend themselves to rolling, drawing into bars or wires down to diameters of less than one tenth of a millimeter.

Reversible alloys have a dilation which varies within very wide limits depending on the proportion of nickel, but when the content of the latter metal is between 35% and 36% steel can have a dilation ten times lower than that of platinum and more than twenty times lower than that of brass, the expansion is not exclusively a function of the nickel content, it also depends on the state of annealing or scorching of the metal lowers at the same time the dilation, finally the stretching succeeding the quenching is another factor of reduction of the dilation.

Nickel steels experience variations in length under the action of time, which are accentuated by a rise in temperature according to complex laws having, however, a great analogy with the variations in volume of glass.

Properly conducted annealing shortens the duration of the perceptible variation of the bars and when a variation of 0.001 mm per meter can be accepted, annealing in SO for 100 hours at 100° is fully sufficient to ensure the permanence of an instrument for at least one year If a consistency twice as great is required, this annealing must be followed by a series of heatings. for example, that the ruler stays at least 400 hours in the region of 80° to 60′, 700 hours from 60P to 10°.

The annealing can without inconvenience be practiced in several times. The use of such a metal was ideal for the construction of clock regulators: we know that a variation of 1 micron (1 hundredth of a millimeter) per meter in the length of a pendulum corresponds to a variation in the duration of oscillation less than 0.05 per day. Now, after six or seven months, a bar of the least expandable alloy takes three or four months to experience a variation of this order. A clock provided with a pendulum constituted by one of these suitably dragged alloys would take a march which, at the end of six months, would experience, by the fact of the pendulum, only a delay in; daytime walking of less than 0.02 seconds in a month.

Today, for the pendulum of clocks, we hardly practice more than grid compensation and mercury compensation, even the first is increasingly neglected because of the extreme difficulty of adjusting many rods. steel and brass which must fulfill the double condition of being perfectly guided and absolutely free.

In the mercury pendulum, the play of the elongation of the rod is counterbalanced by the expansion of the mercury contained either in a vase fisé at the end of the rod, or in a tube replacing this rod as in the Riefier system.

The relative expansion of mercury in glass being about fifteen times greater than that of steel, it suffices that the height of the mercury be the sixth or seventh part of the length comprised between the axis of rotation and the center of oscillation. of the pendulum so that there is compensation.

If the steel rod is replaced by a bar of the least expandable nickel steel, the errors are immediately reduced in the ratio of 13 to 1: a difference of 10′ more or less no longer produces , in the diurnal course, only differences less than half a second and it is this already very small quantity that remains to be corrected by compensation.

It suffices to achieve this, to fix on the rod a lens of a sufficiently expandable metal, resting on a nut screwed directly on the rod. By making the lens of non-expandable brass or nickel steel, a ratio of expansions more favorable than that which results from the combination of mercury and steel will be obtained. „It is easily found that if we retain the proportion of oscillating mass and diameter of the stem used in astronomical pendulums, the total height of the lens will be about 14 centimeters for a pendulum beating the second. The dilatation which is compensated is twelve times lower than in the ordinary system. The difference in temperature from the top to the bottom of the cage and the variations resulting from rapid variations in temperature will be reduced in the same proportion. In addition, the disadvantages resulting from the oxydation of the mercury, its evaporation, the variation in the shape of the meniscus and its mobility will be avoided.

There is a point to which it is advisable to draw further attention, it is the possibility of arriving, in the use of new alloys. to full compensation. When one associates mercury with steel, one establishes the compensation for two determined temperatures, but one renounces by the intermediate or external lemperalures an exact compensation. In fact, for it to be complete, it is necessary that the ratio of the two expansions be the same at all temperatures, a condition which is fulfilled when the two terms of the dilation formulas are separately in the same ratio.

However, for steel, the second term is important whereas it is almost nil in the mer-cure. There is therefore, in the system in use, an advance at intermediate temperatures and a delay at extreme temperatures.

With nickel steels, we can choose an alloy which gives a ratio of two terms identical to that of the metal chosen for the lens and we will thus have achieved the compen-salion complete at all the temperatures at which a clock can be exposed.

Recalling that in the course of his thesis he indicated the reservations required by the use of new alloys because of their variations over time, Mr. Ed. Guillaume adds: The pendulum, even of high precision, is the instrument where this defect has the least importance.

In a clock, irregular and accidental variations are much more dangerous than slow and systematic variations whose law is known. Moreover, as has been said, these variations can easily be reduced to ½o of a second in three months for daytime running.

La Fédération Horlogère, June 30, 1898

Charles-Édouard Guillaume’s Praise

Charles-Édouard Guillaume gave much of the credit for the development of practical Invar balance springs to Paul Perret, though his contributions were later ignored or marginalized. The following article in Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie was written by Guillaume and clearly credits Perret.

Guillaume again gave Perret credit for his contribution at the so-called Conference Guillaume in La Chaux-de-Fonds on November 12, 1903, shortly before Perret’s death. He writes the following, as reported in Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie: