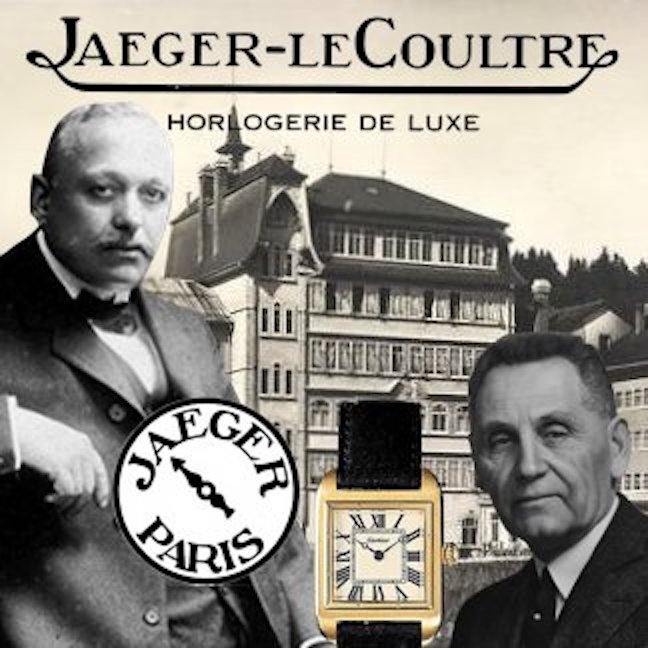

Most enthusiasts could instantly name the watches pictured below, but they’d be wrong: This isn’t a Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso, its an Eska Sesame! By the 1980s, Jaeger-LeCoultre’s signature model was forgotten and the company was struggling to survive. Yet just a decade later, the Reverso would lead the entire industry back from the brink. This is the story of the fall of Jaeger-LeCoultre and the resurrection of the Reverso.

Image: Europa Star, 126, 1981

This article is part of a series on the complex history of Jaeger-LeCoultre. Read more articles in this series by clicking the links below!

- How Edmond Jaeger and Jacques-David LeCoultre Joined Forces

- The Nadir of Jaeger-LeCoultre and the Reverso

Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso: The Once and Future King

Although today’s Jaeger-LeCoultre marketing would have you believe that the Reverso model has been the signature of the brand for nearly 90 years, nothing could be further from the truth. Sure, the Reverso was quite popular in the 1930s, but it quickly fell out of favor and was forgotten. The model was completely absent from the company’s catalogs for decades.

You would probably also love this excellent post from Le Monde Edmond about the Patek Philippe Reverso!

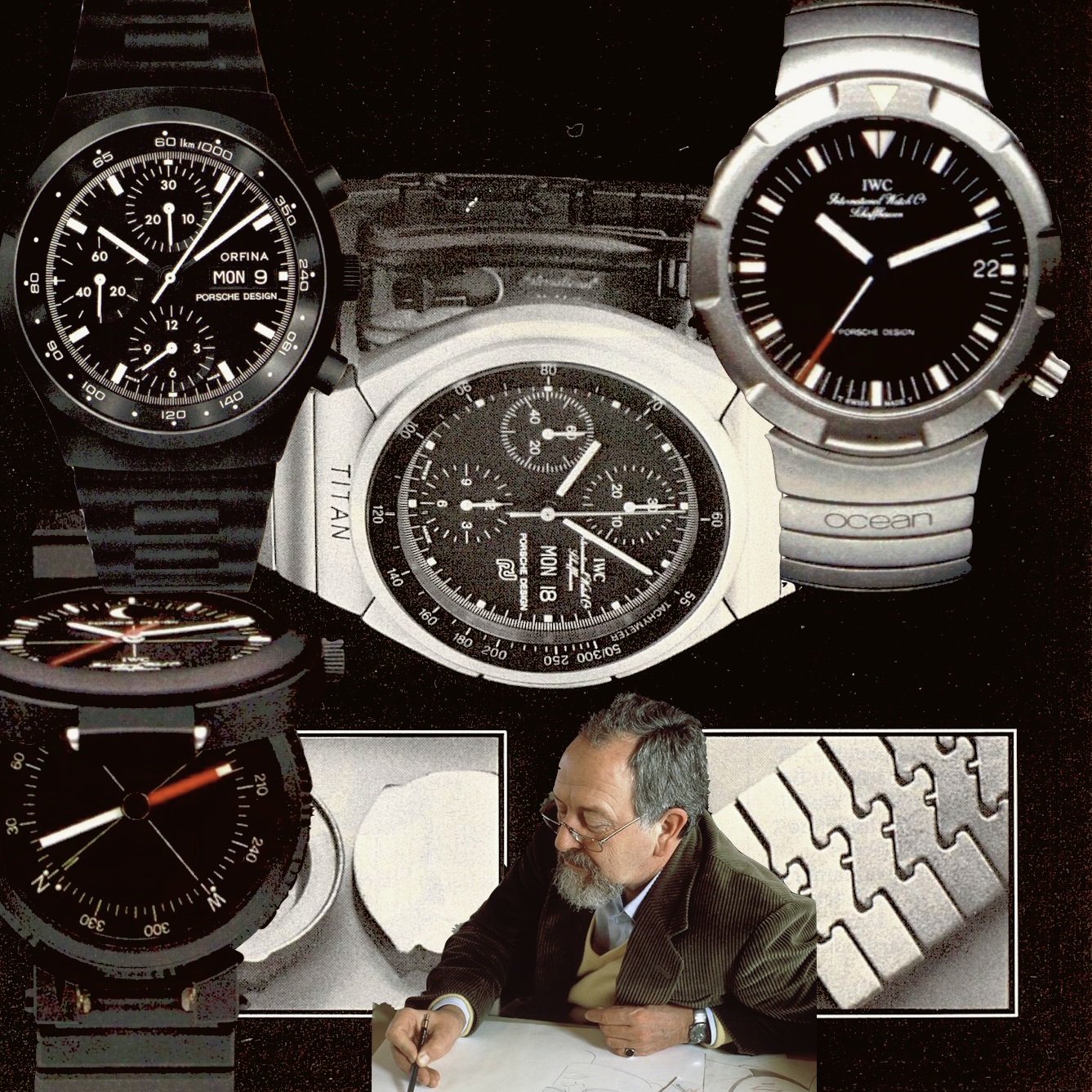

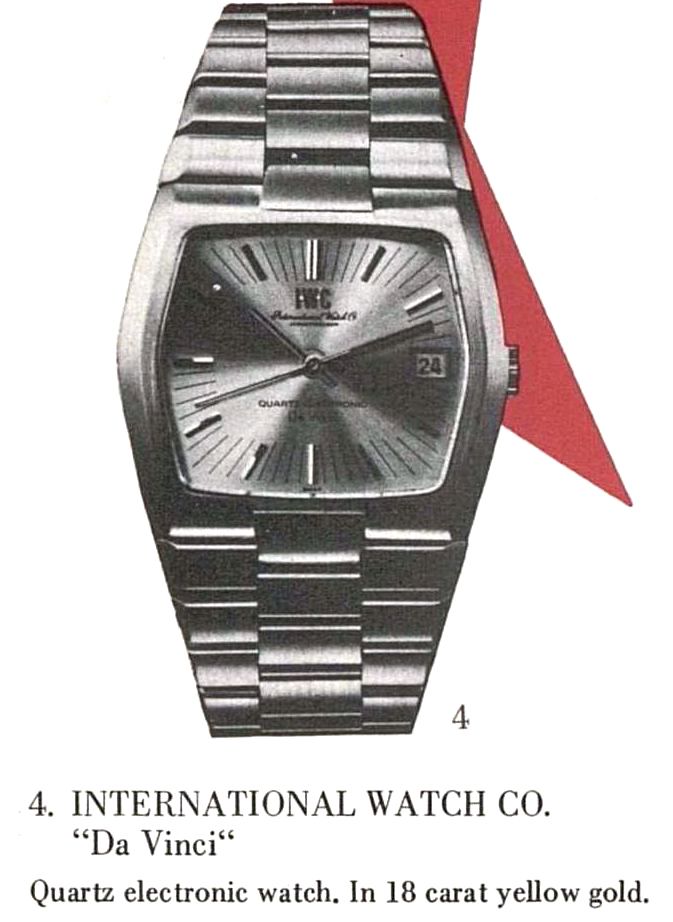

In 1972, as the story goes, the Italian distributor for the struggling brand uncovered a cache of unused Reverso cases and asked Jaeger-LeCoultre to complete them. The design would have seemed antiquated by that time, with avant-garde digital and quartz watches in vogue, but this effort must have been successful because Jaeger-LeCoultre decided to revive the model officially at the end of the decade.

Jaeger-LeCoultre was in dire straits in the late 1970s. The company had been combined with Favre-Leuba in 1969 but was not faring well. In 1978, desperate for money, 65% of Jaeger-LeCoultre was sold to VDO Automotive, which had just purchased IWC as well. It would be another 2 years of restructuring before Günter Blümlein took the helm of Jaeger-LeCoultre and IWC to steer clear of the quartz crisis.

In 1979, news came from the Basel Fair that the revival of the “Reverso” watch was imminent. But Jaeger-LeCoultre was clearly still working on the design, since the illustration used at the Fair showed a concept lacking the usual styling, notably the inscribed lines above and below the dial. A few months later, one of the suppliers for this new Reverso advertised their curved sapphire glass with a photograph of a ready-for-production Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso. Yet this new Reverso was touted more for the quartz Cal. 601 movement than as the return of an icon.

Image: Europa Star 115, 1979

Image: Europa Star 118, 1979

Introducing Eska and Royce

S. Kocher & Co. SA was founded in Granges in 1918, developing the Eska and Royce brands over the next 60 years. The Royce name was used on less-expensive models, emphasizing style and value, while the Eska name was used for higher-end watches for ladies and gentlemen. Intriguingly, Eska produced a watch with a reversible case in the 1930s, and this is often called a “reverso” as well. But it was closer in style to the Cartier Tank Basculante than the Jaeger Reverso.

Image: Europa Star 85, 1974

The sister brands evolved through the 1950s and 1960s, with Royce creating a number of interesting sports watches. One important model was the “Mexico” line, pictured at center above, which sported a synthetic case and was available in many different colors. Kocher was slow to adopt quartz movements, preferring to dive into chronographs (including an early Valjoux 7750 model) with Royce and expensive novelties with Eska.

By the 1970s, Eska was best known for coin watches, diamond-paved ladies models, and jewelry watches. It is at this time that Kocher closed their Granges manufacturing operation, relying on third party development and construction.

Eska Sesame: The Other Reverso

Image: Europa Star, 123, 1980

Eska was better able to compete in the late 1970s, leveraging ETA quartz movements and third parties to produce novel and fashionable cases and dials. “We wish to create models that can be considered to be both fashion accessories and precision instruments,” claimed managing director Eric Kocher in 1981.

A wide variety of models soon appeared, many resembling successful watches from other brands. Eska sold coin watches like Audemars Piguet alongside a cushion case model ripped from Gérald Genta’s sketchbook. Certainly some of these were modestly-original designs, but many appear to be assembled from off-the-shelf components.

Perhaps this explains the Sesame. But the design is almost too perfect: Looking close, we see the same conical lugs, rounded case profile, and three-stripe motif above and below the dial. The case dimensions appear spot-on as well. Looking at the detailed photos in this Flickr set, it seems clear that this isn’t a knock-off: It’s a Reverso! The cabochon crown and dial details are the only differentiators.

Image: Europa Star 123, 1980

Image: Europa Star 123, 1980

Given the precarious financial situation of Jaeger-LeCoultre at that time, perhaps the Eska Sesame is literally a Reverso. Could the supplier of the new Reverso case have offered extra inventory to Eska? Or perhaps Jaeger-LeCoultre themselves were responsible, believing the newly-resurrected Reverso was a mere novelty. Regardless of the reason, this Jaeger-LeCoultre knock-off demonstrates the low-point for that company and model.

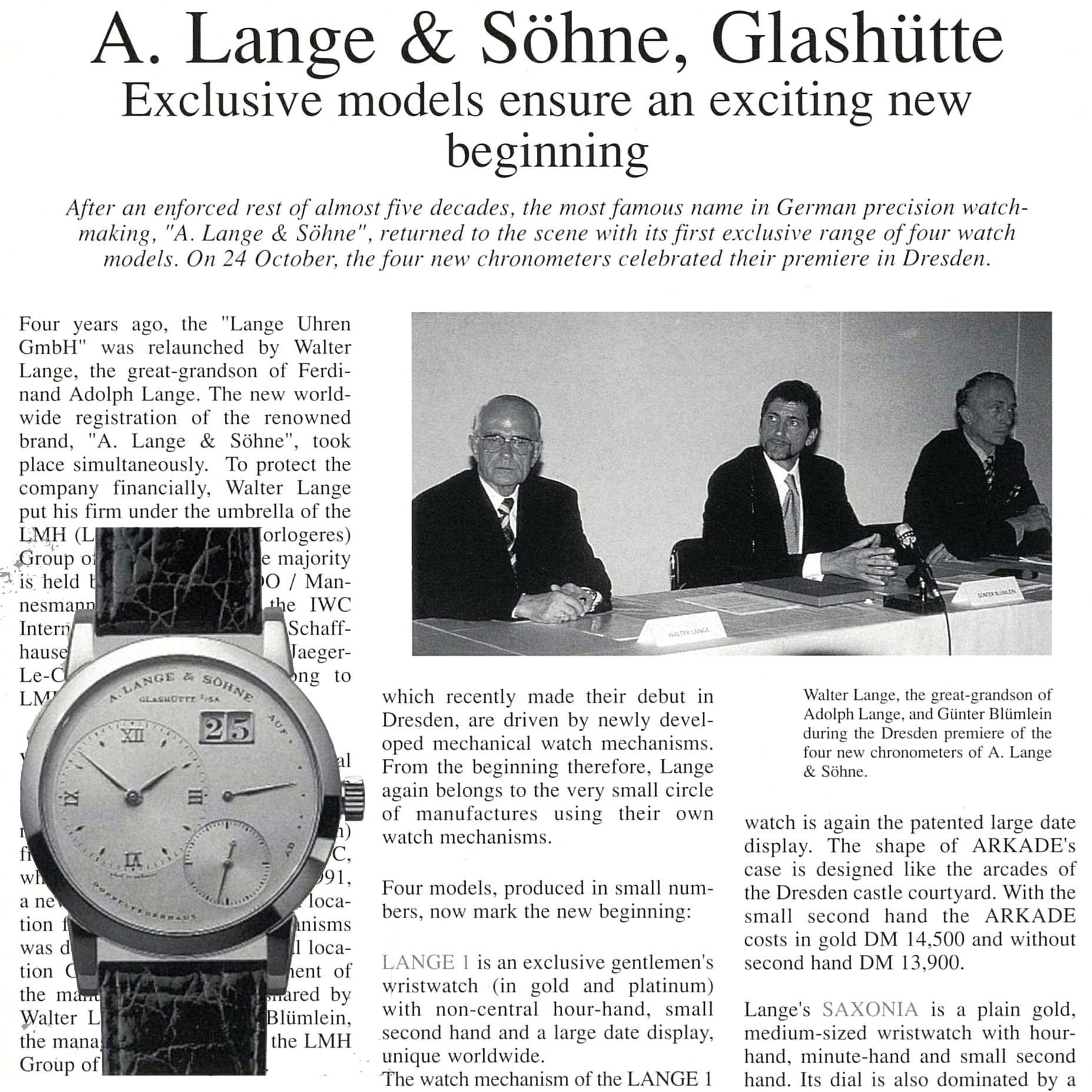

Günter Blümlein and the Resurrection of Jaeger-LeCoultre

VDO wasn’t sure what to do with Jaeger-LeCoultre and IWC, but Günter Blümlein saw the opportunity. He took the lead of both brands in 1980 and began to put the house in order. Although this was the height of popularity for quartz watches, Blümlein believed that a new market for high-end mechanical watches was opening. He directed the watchmakers in Schaffhausen and Le Sentier to create complicated new models that would bring a flood of new revenue.

At the same time, Blümlein began a complex series of financial transactions designed to extricate the high-end watchmakers from their industrial and financial ties. In 1981, they purchased the watchmaking interests of Jaeger, resolving half a century of naming confusion. Blümlein repurchased the shares owned by Vacheron Constantin and a local bank, quickly selling 40% of these shares to Audemars Piguet to raise much-needed cash. In 1990, Blümlein’s company financed the revival of A. Lange & Söhne, creating the first luxury watch trust, Les Manufactures Horologères (LMH) the following year. Mannesmann (who owned the rest of Jaeger) bought VDO, Vodafone bought them, and Richemont bought the entire watch group (including Audemars Piguet’s share) for CHF 2.8 billion in 1999. Sadly, Blümlein would die of leukemia on October 1, 2001.

Image: Europa Star 140, 1983

In 1983, Jaeger-LeCoultre re-focused on the Reverso, reintroducing the historic model as part of the brand’s 150th anniversary celebration. Yet here again, the Art Deco-styled model failed to make much impression on the market. The modern, streamlined Reverso II launched shortly after is also mostly forgotten today. Nevertheless, Jaeger-LeCoultre and IWC introduced a series of complicated models throughout the 1980s, including the Moonphase Watch, Perpetual Date, and Le Grand Réveil from Jaeger-LeCoultre and Kurt Klaus’ remarkable Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar and Grande Complication from IWC.

Blümlein and Jaeger-LeCoultre CEO Henry-John Belmont saw the promise of the Reverso and made the model the focus of the company for the 1990s. This began with the 1991 release of the haute horology 60ème model, celebrating 60 years of the Reverso. Its “Grande Taille” case was large enough to house significant complications, including a tourbillon, minute repeater, and perpetual calendar in 1993, 1994, and 2000. These halo models brought attention to Jaeger-LeCoultre and the Reverso became iconic once more.

The Grail Watch Perspective: The Knock-Off Reverso

It’s not clear whether Eska sold a re-badged Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso, used the same suppliers, or just created a remarkable knock-off. But this obscure model says a lot about Jaeger-LeCoultre’s fortunes in the late 1970s and the remarkable rise of the company and it’s signature product since then. Today, there is only one Reverso, and Jaeger-LeCoultre continues to introduce new sizes and complications. This classic model has come a long way from the leftover cases of the 1970s to the “grande complication” of 2006!

Leave a Reply