Regular Grail Watch readers might have noticed that I have begun using the archives of Europa Star rather heavily in my research. The editors noticed as well, and have invited me to be a contributing writer to that fine journal. My first piece was published today, and delves into the history of an iconic model, IWC’s Da Vinci. The archive brought me fantastic information and illustrations, as we will discuss today.

The Importance of the IWC Da Vinci

IWC has used the Da Vinci name on a few key models over the years:

- One of the first quartz watches

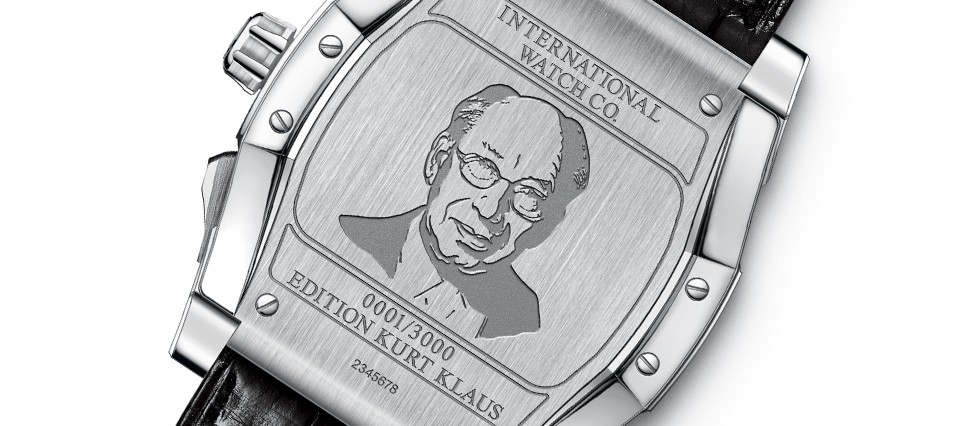

- A complicated perpetual calendar/chronograph model that helped re-ignite interest in mechanical watches (designed by Kurt Klaus)

- One of the first ceramic watch cases

- IWC’s home for Jaeger-LeCoultre’s “Mechaquartz” chronograph movement

- A split-seconds chronograph function (designed by Richard Habring)

- A line of dress watches with tonneau cases

Some of these are obviously more important than others, but this model name really doesn’t have the relevance today that you would think.

I would start by arguing that the 1985 IWC Da Vinci chronograph perpetual calendar is one of the most important watches in the history of horology. The remarkably-simple perpetual calendar mechanism, which the legendary Kurt Klaus reportedly designed in his head while walking his dog, was entirely novel. It was combined with one of the most important automatic movements of the last century, the Valjoux 7750, which was just awakening from its slumber. And the case featured a new and novel hinged strap attachment that allowed a large (by the standard of the day) watch to sit flush to the wrist.

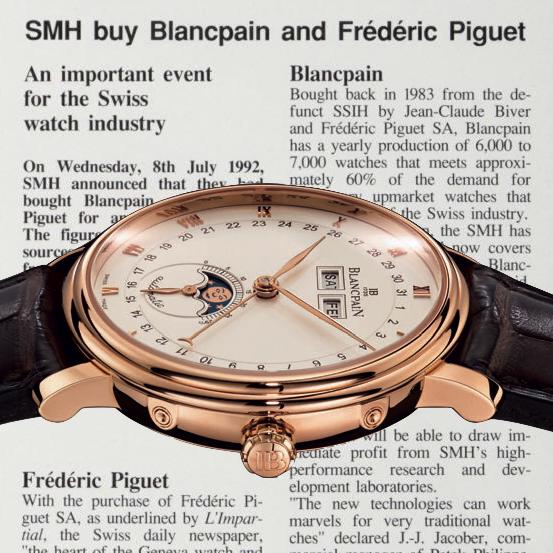

But the importance of the 1985 Da Vinci is what it meant to the industry. Günter Blümlein, who I mentioned recently when discussing the Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso, saw that a moderately-expensive, impressively-complex automatic watch could turn the tide against practical but simple quartz watches. The Da Vinci was that watch, and it single-handedly jump-started interest in mechanical watches. Within a few years, a mechanical watch festooned with subdials and hands was the halo model for every company. And Klaus’ approach of adding complications to an existing automatic base was the template for the resurgence of ETA, Dubois Dépraz, and F. Piguet.

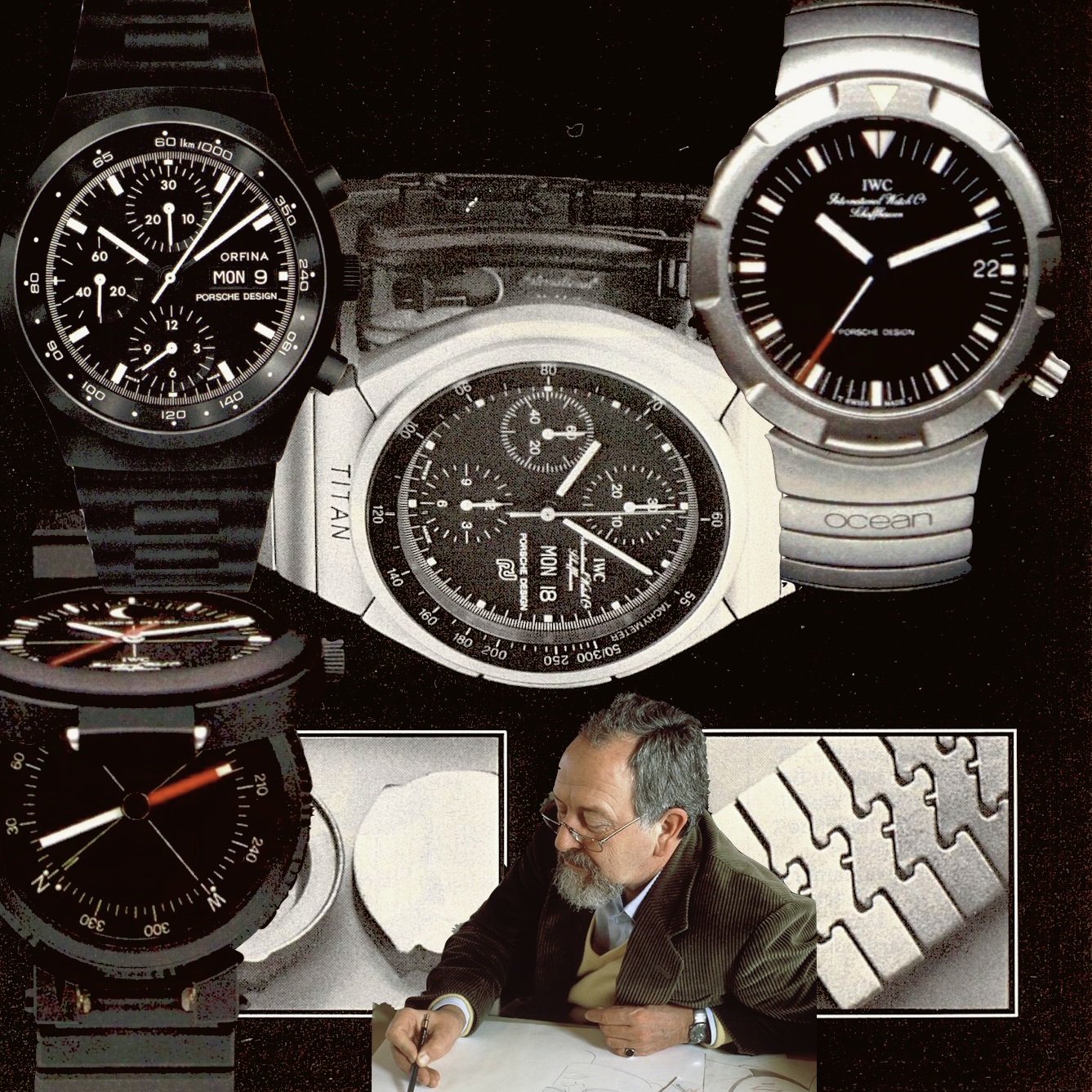

Image: Europa Star 163, 1987

Key IWC Da Vinci Models

Image: Europa Star 68, 1971

The very first IWC watch to bear the Da Vinci name was an interesting quartz model with a hexagonal case. Although there is some mystery as to whether this was IWC’s first quartz watch (a question I will soon investigate in more depth), there is no doubt that the Da Vinci was IWC’s premier quartz model at the beginning of the 1970s.

The novel case is said to have been designed by Gerald Genta. This seems quite likely, as it incorporates many of Genta’s signature elements, from the bezel-less cushion design to the complicated integrated bracelet.

Two things surprised me while investigating this original 1971 Da Vinci model in the Europa Star archives:

- The case appears to have been used a year earlier in a high-end automatic model not called “Da Vinci”

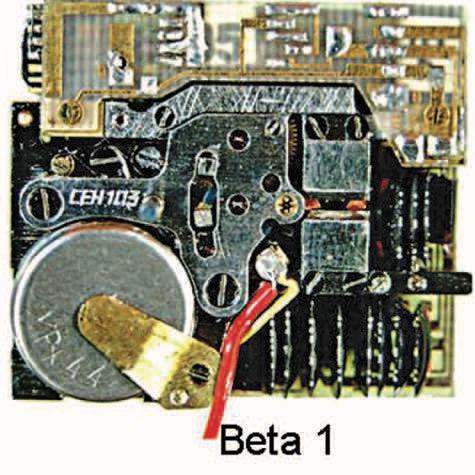

- IWC’s original Beta 21 quartz watch, pictured in coverage of the 1970 Basel Fair, uses an entirely different case and is also not called “Da Vinci”

Image: The Eastern Jeweller & Watchmaker (Europa Star) 117, 1970

I will investigate this more deeply in a future article here on Grail Watch, but suffice to say that the oft-repeated story, that the hexagonal Da Vinci was IWC’s first quartz watch, does not appear to be correct!

As mentioned above, the 1985 Da Vinci chronograph perpetual calendar is perhaps the most important model of the line. But the very next year saw another impressive model. The 1986 Da Vinci Black uses a ceramic case, a first for IWC and one of the first in the industry. The case was primarily constructed of zirconium oxide but also included steel and gold elements, giving it an odd look that is not quite in line with today’s tastes. But it was nevertheless a key model for the company!

Note the glass vial in the photo: It contains the tiny replacement component needed to update the four-digit year wheel, seen between the 7 and 8 markers on the dial, in the year 2500! This was a key advertising element for IWC, as they presented both the capabilities of the perpetual calendar module as well as the assumed longevity of a mechanical timepiece. The company again marketed this in 1999 as the “19” became “20” at midnight on December 31.

A smaller Da Vinci appeared in 1988, both physically and in terms of market appeal. Although IWC made the most of the mechanical Da Vinci, the next version used a quartz movement! Until the 1980s, quartz movements were limited to displaying the time and calendar. At first, adding complications would have taken up too much room and drained the battery too quickly. There was also the question of torque, since early stepper motors were hard-pressed to move a day and date mechanism, let alone all the other wheels needed for complicated models. Instead, quartz development focused on reducing the size of the movement, giving IWC an opening with the complicated Da Vinci.

Image: Europa Star 170, 1988

In 1987, IWC’s sister company Jaeger-LeCoultre introduced the “Mechaquartz” movement, Cal. 630, which brought the Da Vinci’s look to the realm of quartz. This revolutionary movement incorporated two separate stepper motors: A high-torque motor advanced the time and calendar wheels one step per second while another pushed the chronograph wheel train forward four times as fast. Despite this complexity, it was 40% smaller than any other chronograph movement. IWC used Cal. 630 in the Da Vinci (with moon phase) as well as the Portofino and Ingenieur models. But the perpetual calendar was missing.

The next mechanical Da Vinci added another important historical complication: A split-seconds chronograph. Reportedly designed by Richard Habring, the rattrapante mechanism had originally been featured in the legendary Il Destriero Scafusia grande complication of 1992. Adding another hand was a worthy refresh of the 10-year-old Da Vinci model when it appeared in 1995. But the industry had moved on by this time, and the legendary complicated watch was looking dated.

Surprisingly, IWC seems to have skipped the 20th birthday of the Da Vinci perpetual calendar, waiting until 2007 for a redesign. The new case abandoned the round shape and hinged lugs for a return to the original tonneau shape. Indeed, there were two different cases produced: Complicated models had a rounded case with attractive but conventional shape while the simple Da Vinci Automatic is a dead ringer for the 1971 original!

Let’s start with the complicated models. Kurt Klaus’ perpetual calendar mechanism was only found in a limited edition model featuring his signature on the dial. Previously featured here on Grail Watch, this is a marvelous watch and a steal at typical used prices! Then there was the new Da Vinci Chronograph, an unlimited model with a novel hour-and-minutes subdial at 12:00 for the chronograph mechanism. This gives it a lovely balanced look, complementing the running seconds and date window at 6:00. These models are really quite attractive and it’s surprising that they didn’t get more market traction or attention from collectors today.

I personally find the simple Da Vinci Automatic not that attractive at all. The design is harmonious and I appreciate the faceted case but it’s just too busy and retro for my tastes. But this is indeed what makes it special! You see, it is a faithful update to the original quartz Da Vinci from 1971! Look at the design of the case, with the wide central lugs, and the long minute markers. The hands and hour markers are quite similar as well. In this context, the design suddenly makes sense. Indeed, it blossoms!

Image: Europa Star 288, 2008

Subscribe to the Europa Star Club for just 99 Euro. It’s well worth the money, and you’ll get to read more of my contributions in coming months!

The Grail Watch Perspective

The Europa Star archive gives researchers and enthusiasts a unique window on the history of horology. It is remarkable to see the development of the industry as a whole through 70 years of the magazine, and just as useful to examine the history of a single model. I was thrilled to be able to contribute my exploration of the IWC Da Vinci line to Europa Star, and look forward to my next piece for the magazine.

As for the Da Vinci itself, I have a lot more to say. Watch this space for a dive into the history of the Centre Electronique Horloger (CEH), and the fascinating backstory of the world’s first quartz wristwatch. I’ll also be looking deeper to unravel the mystery of the first IWC Da Vinci.

Leave a Reply