On January 12, 1979, the Swiss watch industry announced the thinnest watch ever made: The Delirium, developed and produced by Ebauches SA for Concord, Eterna, IWC, and Longines, measured just 1.98 mm thick. It wasn’t a big seller, but that wasn’t intended; the Delirium was a PR exercise to show the world that the Swiss were innovating like the Japanese and would stand their ground in the quartz market. And the novel design of the Delirium, which embedded the movement into the case back, would lay the foundation for another critical announcement four years later, the Swatch.

This article accompanies Episode 2 of The Watch Files, a podcast from Europa Star and Grail Watch. Listen to “02 The Thin Watch War: Delirium and the Swatch“ and subscribe now!

The Rise of Japanese Quartz

Although the Delirium was the creation of Swiss engineers at Ebauches SA, it would not have existed without outside pressure. Japanese and American companies were rapidly advancing quartz technology after bringing the quartz watch to market alongside the Swiss in 1970. While ESA, Omega, Girard-Perregaux, and others were trying to create the best high-end quartz movement, Seiko, Ricoh, Texas Instruments, Intel, Motorola, and others were simplifying and commoditizing the technology.

Seiko was innovating quickly in analog quartz movements, brushing aside the pioneering Astron Cal. 35 almost before it was launched and introducing wave after wave of improved movements before the Swiss were even able to revise their earliest designs. Once quartz watch production really got under way in 1972, Ebauches SA’s ESA Cal. 9180 was competing with better-developed alternatives from Seiko and Ricoh. And the American industrial giants soon joined the battle as well.

By the middle of the decade it was obvious that the Japanese were far ahead of the Swiss. Seiko and Citizen were producing excellent and reliable quartz movements and these were attracting customers away from the traditional Swiss brands. Seiko was introducing one or two movements a year by the middle of the 1970s, and prices had dropped to mass-market availability.

Seiko saw an opportunity to develop an extra-thin quartz movement and delivered their Cal. 41 in 1974. Although not particularly thin by today’s standards, the 3.8 mm height was much less than competing movements. And Cal. 41, like other contemporary Seiko quartz movements, was well-developed with replaceable components for easier service and upgrades.

Thin Quartz For America

The American watch market was unlike anything else in the world. Although it was the leading post-war economy, America had no taste for luxury watches. Most Americans purchased domestic brands or inexpensive and often re-branded Swiss watches. Rolex and Omega found success mainly as tool watches, with the Rolex Day-Date “President” finding a market mainly among Texas oilmen and politicians.

This is the world Gedalio “Gerry” Grinberg stepped into. Leaving Cuba after the Revolution there, he became the American distributor of Piaget and successfully pushed the brand as a must-have luxury accessory among the New York elite. His company, North American Watch, soon added Corum, with their “coin watch” becoming another fashionable accessory. And Grinberg worked with important jewelry houses like Tiffany and Van Cleef & Arpels to stock his brands.

Grinberg’s focus on fashionable thin watches lead him to acquire his own brand. Unable to purchase Movado, he instead positioned Concord as his luxury brand for America. But Concord needed a world-beating offering to get attention and sales.

In May 1978, Citizen introduced the Exceed Gold, an ultra-thin watch with a remarkable 0.98 mm thin movement. The production watch measured 4.1 mm thick, due to the height of the battery and hand set. Although Citizen was not widely available in the United States, this watch showed the potential for an ultra-thin quartz movement. Citizen used the expensive ultra-thin Cal. 790 to lure buyers into their showrooms, but most walked out with the more practical Cal. 7920 or 7930, which were twice as thick but less expensive and more robust.

Seiko was Citizen’s main rival, and they had long used the same strategy for their offerings, with high-end models cased in gold calling attention and widely-available steel offerings drawing sales. Seiko was also emphasizing the thin profile of their quartz offerings, steadily dropping millimeters throughout the decade. And Seiko was rapidly establishing itself in the American market, with wider distribution and name recognition than Citizen, Ricoh, Orient, and other Japanese brands.

On July 20, 1978, just a few months after the Citizen announcement, Seiko announced the slimmest watch in the world. Their new Cal. 9320 measured just 0.90 mm thick, narrowly edging aside the Citizen offering, but they paired it with an amazing 2.5 mm thin case.

The watch was incredibly rare and expensive, at US$5,000, but the company used this to their advantage as well. They convinced Tiffany & Co. to stock the watch in their New York showroom, something unheard-of for a Japanese watch brand. Just 7 examples were released for sale at first, with some reports claiming that just 15 were ever produced. But Seiko had made their point.

Switzerland Strikes Back

The Seiko ultra-thin watch was a shot across the bow of the Swiss luxury watch industry and it surely angered Grinberg. After all, high-end thin watches were his forte and he had nothing that could compete with these. Even before Seiko’s announcement with Tiffany, Grinberg headed to Switzerland to set things right.

Many watch movement producers in Switzerland had been consolidated by the late 1970s under the umbrella of Ebauches SA. Lead by technical director André Beyner, Ebauches SA was best positioned to construct the thin quartz watch Grunberg demanded. And demand he did, offering CHF 2 million if the company could produce a watch thinner than Seiko.

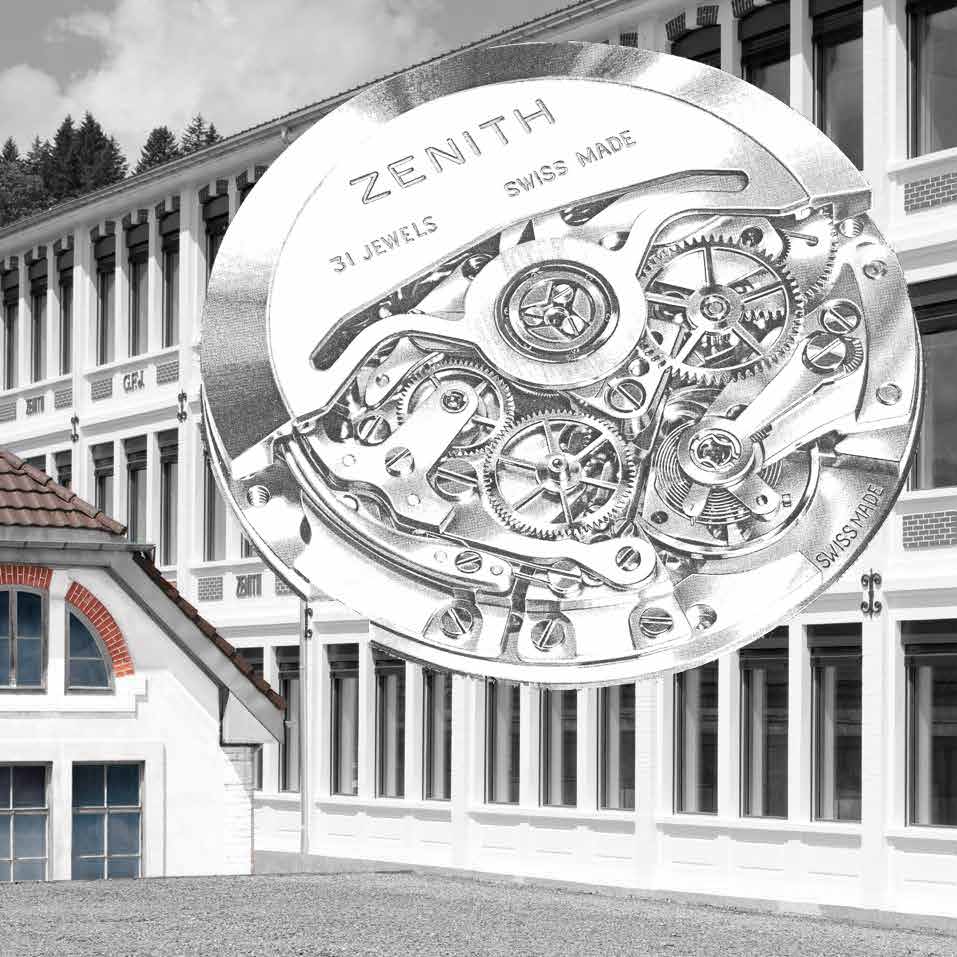

Work proceeded at a furious pace. The legendary movement designer Anton Bally developed a movement that spread the components horizontally to reduce thickness. Beyner decided to integrate the movement and case into a single unitary case, developed by Maurice Grimm. All the components were attached directly to the unitized body, with the dial, hands, and crystal completing the watch. The Swiss conglomerates were reeling as quartz movements gained market share, and the now-legendary Ernst Thomke was in charge of production. He took charge of the “Delirium Tremens” project (and soon all of Ebauches SA) and drove it to production.

Image: Europa Star 115, 1979

On January 12, 1979, at joint press conferences held around the world, Ebauches SA announced the Delirium. Easily the world’s thinnest watch, it measured just 1.98 mm thick, surpassing the legendary Jean Lassale mechanical watches shown just a few years earlier. Most importantly to Gerry Grinberg, the new Concord Delirium was the talk of the town in New York, with Tiffany & Co. featuring “the thinnest watch ever made” in their advertising and their showroom.

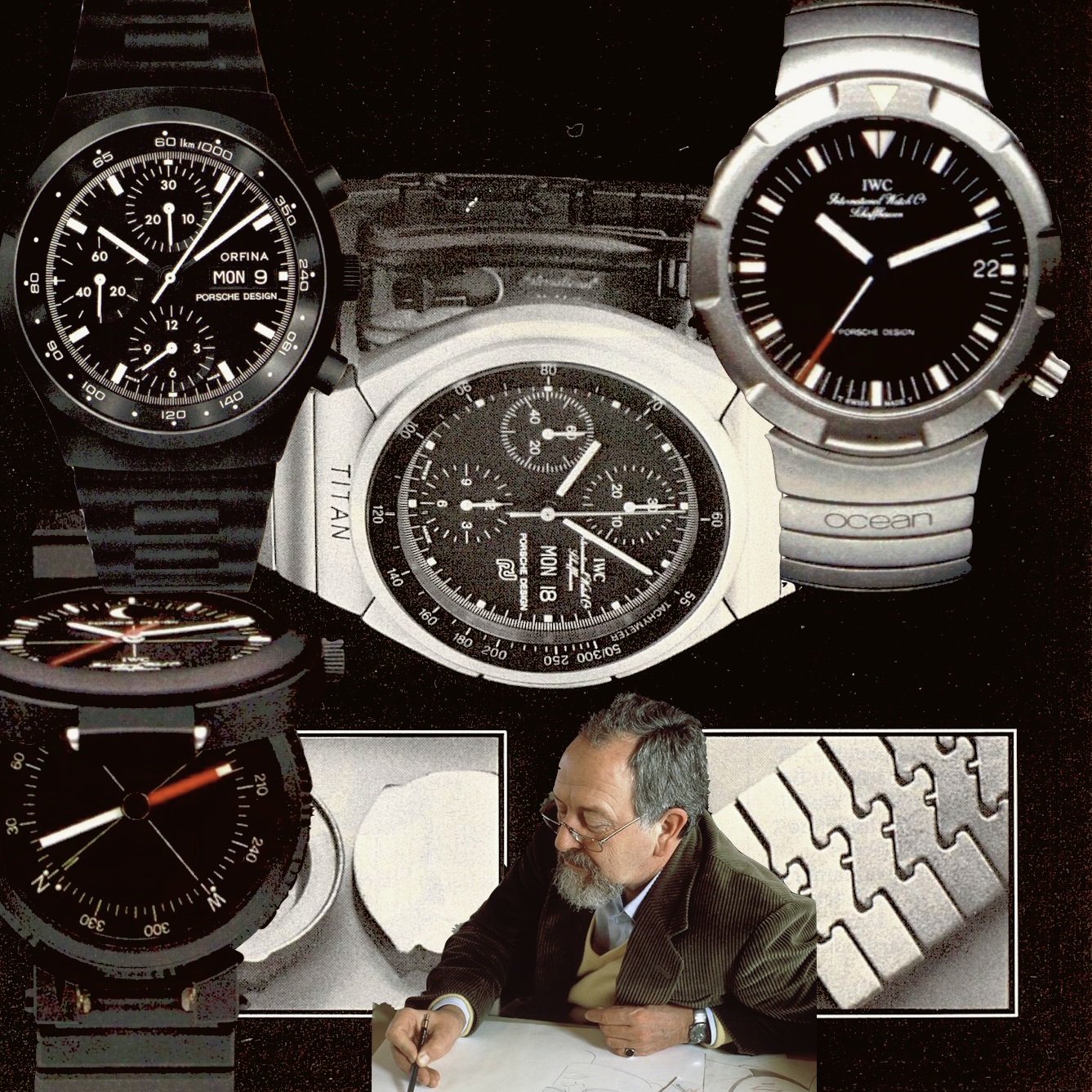

The watch would be marketed in the United States by Grinberg’s Concord brand, with Longines and Eterna offering models in various markets. Many promotional images even featured the Ebauches SA logo on the dial. And at least one example (which I recently purchased for my collection) features IWC branding and is known as IWC Ref. 3000. Eterna and Longines were part of the General Watch Company alongside Ebauches SA as part of ASUAG, so it is no surprise that they were selected to sell the Delirium. And Grinberg put up the development money, so it is logical that Concord would be a major player. But IWC was totally unrelated to all of these companies at the time, and had just been purchased by VDO along with Jaeger-LeCoultre, so it is puzzling why they were involved at all.

The branding of the Delirium watches is somewhat confusing. Certainly Concord is most associated with the watch today, and the company continues to produce a line of watches branded “Delirium” today. However, this model name originated at Ebauches SA and was widely used in promotion at the time to refer to all of their ultra-thin quartz watches. Longines called their model the “Longines Quartz” while Eterna marketed theirs as the “Eterna Espada”, though that name was not included on the dial.

One reason Citizen was unable to capitalize on their thin movement was the battery. The company simply lacked a sufficiently thin battery to deliver a watch under 4 mm. Seiko too had to leave room for a comparatively thick battery inside their ultra-thin watch. But the Swiss had a secret weapon: Renata, now part of the Swatch Group, developed a battery just 1.1 mm thick. Situated at the 5:00 position under the dial, it was by far the thickest component of the Delirium. But the product could not have existed without it!

As remarkable as the Delirium was, it would not hold its record for long. Just six months later, Ebauches SA announced an even thinner watch. The watch, sold as the Concord Delirium II or Eterna Linea Quartz Skeleton, measured just 1.43 mm thick. It proved impractical to wear, however, and was is not well-remembered today.

In January 1980, Ebauches SA delivered another Delirium watch. It was a ladies model measuring 1.68 mm thick, with a shorter and narrower face as well. It was marketed as the Concord Delirium III, Eterna Linea III, and (confusingly) Longines Delirium 2. Unlike the slightly thinner Delirium II, it was practical enough to be worn, albeit with some care.

The final Delirium delivered by Ebauches SA was the incredible 0.98 mm Delirium IV. The thinnest watch ever produced, the Delirium IV used inscribed crystal discs rather than hands and relied on a special ultra-thin battery and crystal. It was not really a wearable watch, so Eterna labeled theirs the “Linea Museum Watch”. I’ve never seen one outside a museum!

The Thin Watch Aftermath

Seiko and Citizen continued to innovate on thin movements, of course, but Ebauches SA and Concord stole their thunder with the remarkable Delirium. Indeed, Seiko’s later ultra-thin movements (including the amazing 9A85, which measured just 0.85 mm) are often overlooked today.

Perhaps this is because all movements were getting thinner, as documented by Anthony Kable at Plus9Time. Throughout the 1980s, the average new analog quartz movement from Seiko was about 2.5 mm thick. Given the practical requirements of a wearable watch, it doesn’t make much sense to build a 1 mm movement and place it in a 4 mm watch. Instead, most thin watches of the 1980s were 6-8 mm thick, which was enough to wow buyers while also making them durable enough for everyday use.

The most lasting outcome of the Thin Watch War was something else entirely: The Swatch. As they consolidated the various components of the Swiss industry into SMH, Ernst Thomke of ETA and Paul Renggli of ASUAG directed his team to leverage the Delirium design into a more practical and less expensive watch. As Thomke said at the time, “the future is in innovative finished products, aggressive marketing, volume sales, and vertical integration in the industry.”

The “Delirium Vulgare” (“Delirium for the masses”) concept stalled until one fateful day in the 1980s when ETA engineer Elmar Mock was called into Thomke’s office to justify spending CHF 500,000 on an injection molding machine. Mock produced a sketch of a plastic watch he had designed with fellow engineer Jacques Müller, and Thomke roared “I’ve been waiting for this for over a year!”

The design became the Swatch, a mass-produced watch with a molded plastic case. It used the same concept as the Delirium, with the movement parts mounted directly to the inside of the case, but was quite different otherwise. And the success of the Swatch was due as much to Franz Sprecher’s marketing as Mock’s plastic. But there is a direct line from Seiko’s display at Tiffany to Grinberg’s demand for the Delirium to Thomke’s Delirium Vulgare idea to Mock’s plastic case to Sprecher’s “second watch” concept.

The Grail Watch Perspective: The Good War

The Swiss watch industry needed a reason to innovate in the 1970s, and the Thin Watch War brought everything together. The threat of defeat in the face of competition drove Ernst Thomke and Nicolas Hayek to create the Swatch Group and ETA as we know it today. And Seiko and Citizen benefited too, creating compact and reliable quartz movements that power billions of watches.

This article accompanies Episode 2 of The Watch Files, a podcast from Europa Star and Grail Watch. Listen to “02 The Thin Watch War: Delirium and the Swatch“ and subscribe now!

Just am finishing up the 2nd half of The Watch Files episode two while looking at the images in the article (I’ll be reading it this weekend). Really love the vibe of the podcast and I hope to hear more of these educational discussions Stephen & Serge!

Thank you so much, Charlie! I believe these stories are interesting to many watch enthusiasts, and I’m glad we’ve found a few listeners who appreciate what we’re doing.

Thank you for this very nice historical odyssey. I tried on an all gold 1.98 mm Delirium back in a store in 1980. It was 11.000 dollars at the time. The Rolex Submariner was a thousand dollars. Those two together was the price of a new Lincoln Continental.

I love this context! These were some EXPENSIVE watches!