Zenith was “the first manufacture“, one of the greatest watch companies in Switzerland, and the economic force behind Le Locle. Then it was purchased by an American electronics company and ordered to destroy its mechanical watchmaking assets. This is the story of the mighty Zenith, brought low, and returning thanks to a machine tools baron, a humble watchmaker, and two other famous brands.

This article accompanies Episode 3 of The Watch Files, a podcast from Europa Star and Grail Watch. Listen to “03 El Primero and the Birth, Death, and Resurrection of Zenith” and subscribe now!

Zenith, the First Manufacture

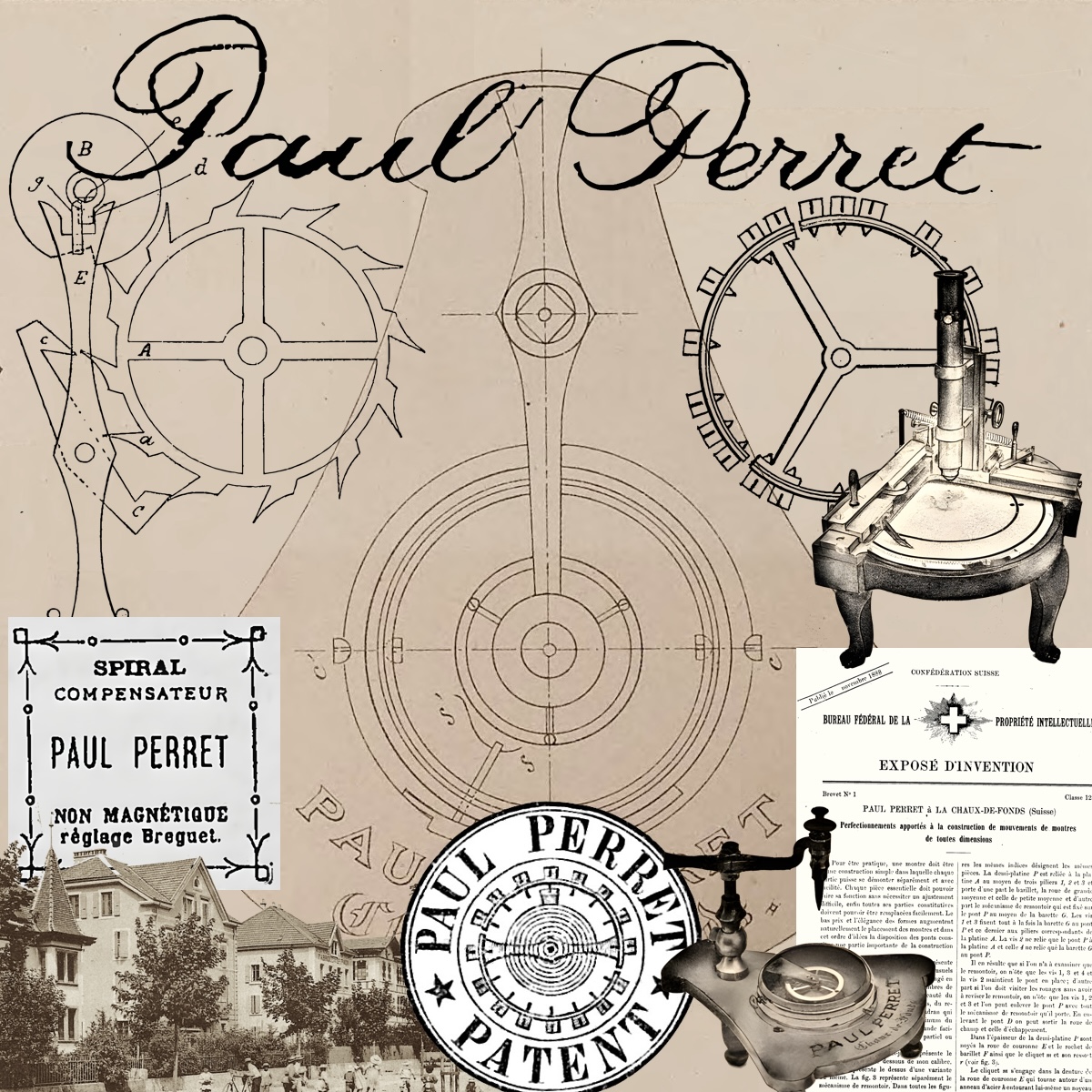

Georges Favre-Jacot was not quite Henry Ford, but he was almost as important to the transformation of watchmaking in Switzerland from an industry of cottage workers to factory production. He founded his “Fabrique des Billodes” in 1865 at the age of 22, locating it in Le Locle, the historic home of watchmaking in the region.

At the time, construction of watches was widely distributed, with individual craftsmen and small workshops producing individual elements from the Swiss Jura valley into France. These were combined by établisseurs like the powerful DuBois family into watches, sold through distributors, and marketed worldwide. The system, established by the great Daniel JeanRichard in Le Locle a century earlier, had created a new industry and helped Switzerland rise after the railroad decimated the viability of local farming.

The International Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876 changed everything. The Swiss établissage system could not compete with mass production of precision watches in Waltham, Waterbury, Elgin, and Lancaster, and customers loved the affordable and repairable watches coming from these huge American factories. Jacques David of Longines attended the exposition and wrote an influential report about Waltham’s prowess. Edouard Favre-Perret amplified this message in writings and a famous speech in La Chaux-de-Fonds: Mechanize the industry or perish!

Image: Longines, 1911

This warning was received loud and clear by many: Jacques David modernized the mighty Longines factory on the Suze river in Saint-Imier. Louis Brandt moved Omega to Bienne/Biel when La Chaux-de-Fonds resisted the call to industrialize. Henri Sandoz studied the American system and established his family factory in Tavannes. And Georges Favre-Jacot poured money into Le Locle to build the largest, most vertically integrated watchmaking operation for his new Zenith brand.

Image: Zenith, 1908

The new Zenith manufacture was not alone in Le Locle, however. A new manufacture, Tissot, was rising on the other side of town. And an important tooling supplier called Dixi was located nearby. Soon, the majority of the working population of Le Locle was employed in watchmaking and associated industries, and companies began establishing in the town to access this labor force.

Martel, founded nearby in Les Ponts-de-Martel, established a factory outside the gates of Zenith and newcomer Universal to produce chronograph movements. After briefly switching to Excelsior Park movements from Saint-Imier, Zenith switched back to Martel, purchasing the company outright around 1959. The Stolz brothers established Angelus nearby to produce chronographs, and Zodiac invented the power reserve indicator in Le Locle.

And Le Locle was home to even more exclusive watches: Ulysse Nardin produced marine chronometers outside Tissot’s gates, and Urban Jürgensen produced chronometers in Le Locle when he wasn’t home in Copenhagen. Two of the most important luxury brands of the 20th century were also located in the town: Henry Moser & Co. and Paul Buhré. Yes, this is the predecessor of that H. Moser!

The Highs and Lows of Zenith and Le Locle

What goes up must come down, and so it was with Le Locle. Decades of labor strife caused issues for the city, and La Chaux-de-Fonds (just down the road) proved more welcoming to investors. Universal moved out before World War II and became Universal Genève, and many others focused more on that city and on Neuchâtel.

For a time it looked like Zenith was strong enough to be a survivor. The company had long struggled to sell in the American market due to their name: The Zenith Radio Company of Chicago was extremely strong after the war and constantly threatened legal action in this important market. In 1968, Zenith merged with Movado of La Chaux-de-Fonds, becoming Movado-Zenith. This allowed them to sell watches in the United States using the respected Movado brand. The next year they became Movado-Zenith-Mondia after adding another La Chaux-de-Fonds company.

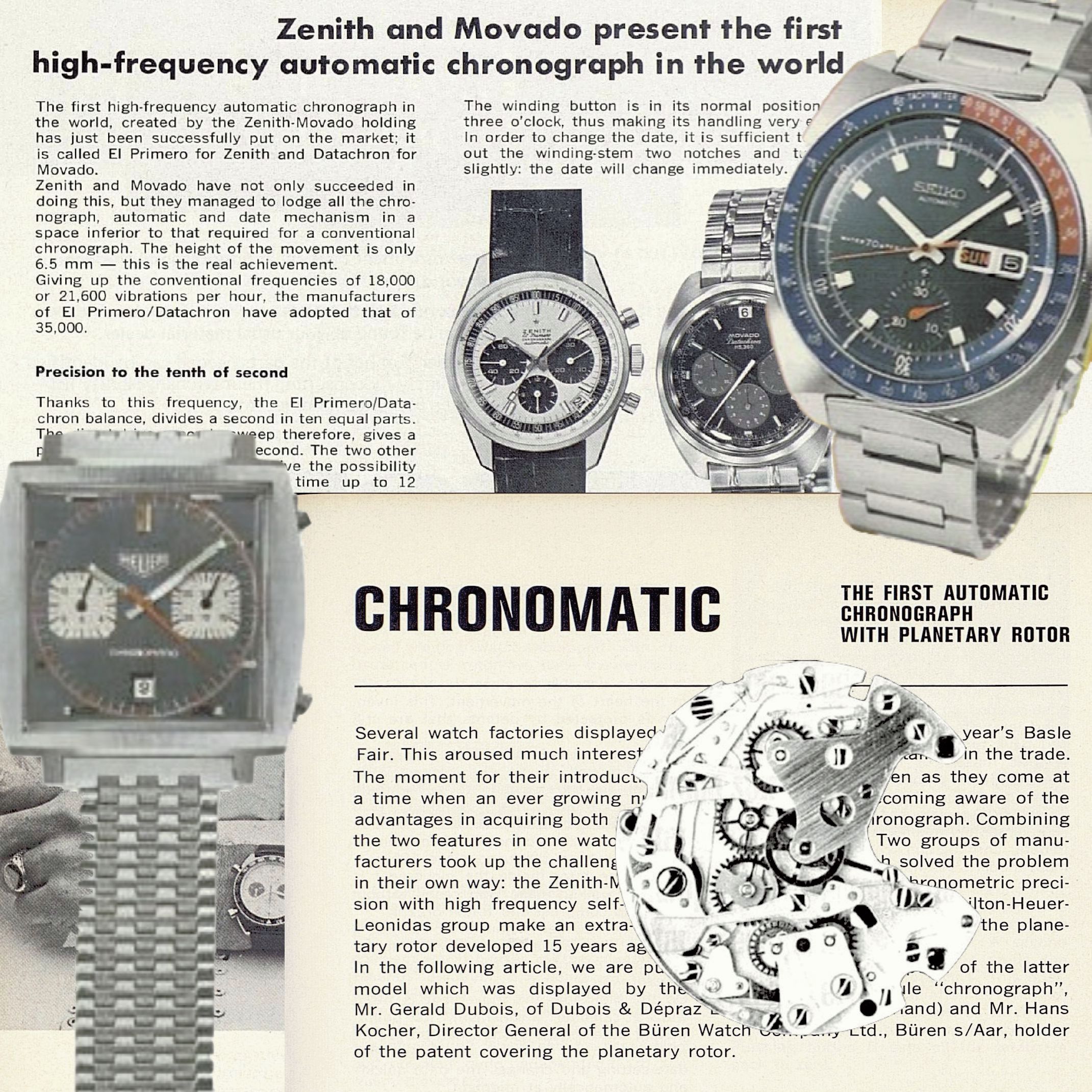

Zenith developed some of their strongest products in this period, including the Defy sports watch line. But it was the world-beating El Primero automatic chronograph movement that truly set the company apart. Developed by the staff brought in from Martel, production of the world’s first automatic chronograph stalled until word leaked about the similar “Project 99”, a joint effort between Heuer-Leonidas and Dubois Dépraz. Zenith rushed to prepare prototypes and scooped that consortium’s announcement.

Image: Europa Star Eastern Jeweller 111, 1969

On January 10, 1969, Zenith and Movado announced their El Primero. Not just an automatic chronograph, this movement was an advanced design overall. It included a “high-beat” oscillator, one of only a few movements operating at 10 Hz (36,000 A/h) and the only high-beat chronograph produced to date. This gave it accuracy to 1/10 second on the central chronograph hand and excellent timekeeping performance overall.

In contrast, the Chronomatic movement announced by Heuer-Leonidas, Dubois Dépraz, Hamilton/Büren, and Breitling on March 3 of that year was something of a letdown. It was an awkward combination of a chronograph module from Dubois Dépraz and a thin micro-rotor movement from Büren. It was mounted “upside down and backwards”, burying the rotor and balance and switching the crown to the 9:00 position. But the Chronomatic was in customer hands before the El Primero was released in October, as was dark horse Seiko’s automatic Cal. 6139.

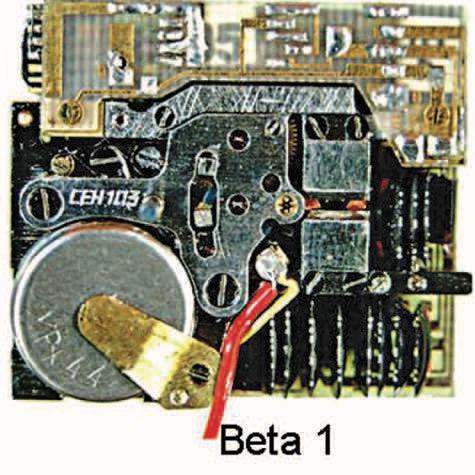

As strong a product as it was, the El Primero launch was overshadowed by anticipation of the launch of the world’s first quartz watches. Longines would announce their Ultra-Quartz just a few months later, and the 1970 watch fairs were packed with quartz watches, including the Beta 21, Omega Megaquartz, Girard-Perregaux Elcron, and Neosonic. Although a quartz chronograph was a long way off (and an analog quartz chronograph decades away), electronic watches were all the rage.

1972: Zenith Buys Zenith

Image: New York Times, June 2, 1971

As the 1960s became the 1970s, the US dollar was incredibly strong compared to the Swiss franc, and the Zenith Radio Company saw an opportunity: They would purchase Movado-Zenith-Mondia and leverage these companies to develop and market electronic watches (and potentially other electronics) around the globe. In June 1972, the announcement was made that Zenith (of Chicago) was buying Zenith (of Le Locle).

The acquisition was not an ideal match. Zenith Radio Company was eager to compete with rivals like RCA and Intersil (which were working with Seiko) and Texas Instruments (which partnered with many companies including Longines). But Movado and Zenith were not actively developing electric, tuning fork, quartz, or digital watches at that time.

Although Zenith was part of the Beta 21 consortium, they did not show a quartz watch at the 1970 Basel fair and do not appear ever to have shipped such a watch. And their post-acquisition “XL-Tronic” movements were produced by Ebauches SA. The first was not quartz at all but was a version of the “Mosaba” tuning fork Cal. 9160. When they did ship a quartz movement in 1974, it was ESA’s early quartz Cal. 9180, not an in-house movement.

For most models, Zenith and Movado were still relying on their mechanical movements: The El Primero and Zenith’s own Cal. 25 movement family. The company remained on the forefront of design, with interesting shared models as well as unique pieces for each brand: The American market loved the slim Movado “Museum Watch” line, while the brash and rugged El Primero and Defy from Zenith remain some of the most attractive watches of the decade.

No More Mechanical Watches!

With the American backing, Zenith quickly began to develop their own quartz movement technology. The result was the “Time Command” Cal. 47, which debuted in 1975 with a novel twist: It used a single quartz movement to drive analog hour and minute hands as well as a digital seconds and calendar display. This so-called “combo movement” was ahead of the times, with similar approaches being a signature of sports watches in the 1980s.

The Time Command Cal. 47 had a lot going for it, but the rapid progress of quartz technology meant it was already a bit outdated the day it was launched. LED displays are power-hungry, so the Zenith only shows the seconds or date on command, at the press of a button. The complex integrated circuit, stepper motor, and LED demanded the use of two batteries. And the unusual combination of LED and buttons meant it was an awkward fit in conventional watch cases.

Zenith did produce a more conventional version of Cal. 47, which moved the LED display to the 6:00 position on the dial. This was used in the Defy line, while the rectangular Futur got all the attention. The company also used quartz movements from Ebauches SA (as did the entire industry) in ordinary time-only watches.

But as late as 1978, Zenith was still relying on mechanical movements for a large number of models. The Defy and El Primero models were still a highlight of the lineup. And the Port Royal and other quartz models had not really taken off.

This situation must have irked the management back in Chicago, who wanted Zenith to be a consumer electronics brand not a maker of “old fashioned” mechanical watches. With Seiko, Ricoh, and Citizen rapidly innovating in quartz watches, it was clear in the second half of the decade that a small company like Zenith would never be able to deliver a world-beating electronic watch.

In early 1978, management in Chicago issued an edict to Le Locle: Stop making mechanical watches and dispose of all tooling and production capability.

This was not an unusual situation for Le Locle watchmakers. Dixi purchased struggling luxury brand Paul Buhré in 1963 and stepped in to save Moser in 1974. But these brands were nearly dead by 1978. Angelus and Zodiac were on their last legs, with the latter salvaged by Dixi the following year. And Tissot was hemorrhaging money, closing their factories in Neuchâtel and La Chaux-de-Fonds and abandoning movement production entirely.

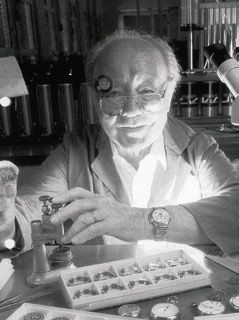

Preserving Zenith: Charles Vermot and Paul Castella

Learn more in my article, How Charles Vermot Saved the Zénith El Primero – In His Own Words

Image: Zenith

The remaining staff at the Zenith factory stopped the production lines and prepared to scrap the machinery. This troubled some staff, and watchmaker Charles Vermot took an unusual step: Before El Primero production ceased, he took detailed notes of the production process, cataloged all the tooling, and carefully preserved everything needed to produce the movement. He also gathered a few thousand leftover ebauches and component kits. Rather than disposing of these parts, he stored them in the attic of the old factory. Vermot had joined Zenith with Martel and had worked on the development of the El Primero.

Zenith and Movado produced only quartz watches starting in 1978, but this was not enough to save the company’s sales. With business faltering, Zenith Radio Company put their Swiss watchmaking operations up for sale shortly after.

Image: Zenith

In late 1978, Paul Castella and Dixi stepped up once again, purchasing Movado-Zenith-Mondia from Zenith Radio Company. Although Dixi already owned a half dozen local watchmakers, none was very large or prosperous. Castella might have been focused on the valuable real estate across the street from his Dixi complex, or he might have had civic pride in mind, recovering a local name to Le Locle. But he clearly cared about watchmaking as well, personally directing operations at Paul Buhré and appearing in public to promote their products.

Zenith was reborn, but had a difficult youth. The quartz crisis raged on, and Dixi’s watch production slowed to a trickle. The Henry Moser & Co. and Mondia brands were quietly retired, with Jean Perret (acquired in 1976) and Zenith receiving most of the focus. Dixi added another historic Le Locle name in 1979, Zodiac. But Swiss watches just weren’t competitive enough to support these companies, or the town of Le Locle itself.

Image: New York Times, June 2, 1971

In 1982, Zodiac was merged with Zenith and positioned as a lower-priced sister brand. Its factory was closed, with Zenith handling production, but sales were slow. Perhaps weary of the continued effort and investment, Dixi began divesting. Gerry Grinberg of North American Watch Company had always wanted to own the Movado brand, and Dixi sold it to him in 1983. Jean Perret was sold to businessman John Buser in 1985, and the Zodiac and Paul Buhré brands were retired soon after.

Only Zenith continued in operation.

Reviving Zenith: Ebel and Rolex

Read Serge Maillard’s article, The Watchmaker Who Saved Zenith From Oblivion, and watch this French-language interview with Charles Vermot

Image: Europa Star 136, 1982

Although the fate of mass-market mechanical watches was sealed, a few visionaries saw a path forward for high-end and complex mechanical pieces. Ebel had emerged as a “must-have” brand by 1980, and wanted a range-topping mechanical chronograph in their collection. They turned to Zenith, since their El Primero was easily the most advanced chronograph movement made in the previous decade.

Consulting with the now-retired Charles Vermot, Zenith management was surprised to learn that a few thousand El Primero movements remained in storage in Le Locle. The company agreed to supply Ebel, and their 1982 chronograph was hailed as a breakthrough for its trendy design and advanced movement. With no mechanical quartz chronograph movements yet on the market, a window of viability had opened.

Image: Europa Star 163, 1987

When IWC’s Da Vinci grabbed the headlines in 1985, with its automatic chronograph and perpetual calendar, Zenith asked Vermot to help restart production. The tooling was unpacked, and in 1986, Zenith introduced Cal. 40.0. The El Primero was reborn!

Around that same time, Zenith was in secret talks with another heavy-hitter. Rolex wanted an automatic chronograph movement to bring their Daytona up to date. Rather than develop their own, they collaborated with Zenith to develop Cal. 4030. Although based on the El Primero architecture, the Rolex movement used a free-sprung balance with a Breguet overcoil and reduced the beat rate to 8 Hz (28,800 A/h) for reliability. It also eliminated the date function, among dozens of other changes. In all, Rolex Cal. 4030 shares only 50% of its parts with the contemporary Zenith Cal. 400.

The Daytona would use a Zenith-based movement from 1988 through 2000, and Ebel sourced El Primero movements until 1995, providing the company much-needed financial stability as it recovered from the quartz crisis. Zenith redesigned the movement in the 1990s, re-architecting the subdials to move the date window, adding a flyback option, and producing a hand-winding version. Today, the El Primero and the Elite are the two pillars on which the company rests.

Amid the rise of luxury groups at the end of the 1990s, LVMH surprised the industry by acquiring TAG Heuer, Chaumet, and Ebel in quick succession in 1999. This set off a scramble for Zenith, which was also added to the group on November 15 of that year. Swatch Group had just purchased Breguet and the dominoes fell quickly: Swatch Group added Jaquet Droz and Glashütte Original and Richemont claimed A. Lange & Söhne, IWC, and Jaeger-LeCoultre the following year.

Dixi was done with watches. Paul Castella died on October 25, 2020 at the age of 100. The family considered selling the machine tools division to Samsung in the 1990s but held on until 2007, when it was sold to Mori Seiki of Japan. The rest of the group remains with the Castella family, and it is said that Le Locle is sometimes called “Dixiland” in their honor. Charles Vermot reportedly only received an El Primero watch and a good meal as thanks for his work. But he also earned the thanks of watch enthusiasts everywhere!

The Grail Watch Perspective: Was Zenith Wrong?

It’s easy to place the blame for Zenith’s troubles on the Zenith Radio Company. After all, they ordered the destruction of one of the greatest watch movements of all time just a few months before disposing of one of the greatest watch companies! But they weren’t wrong: The mechanical watch industry in Le Locle was failing, and would have failed even without the intervention of the American electronics executives.

Compare this story to Büren, which failed just before Calibre 82 was to be released. Or Tissot, which was almost shut down by Ernst Thomke and SMH. Paul Buhré was forgotten and H. Moser & Cie. was reborn. If Zenith had been left alone, it would have crumbled in the 1970s like almost every other Swiss watchmaker; Charles Vermot would not have been there at the end to rescue the El Primero; there would have been no movement to offer Ebel and Rolex; and LVMH would have a different “star” watchmaker.

Coincidence decides who lives and who dies, and history tells the tale as if it was pre-ordained.

This article accompanies Episode 3 of The Watch Files, a podcast from Europa Star and Grail Watch. Listen to “03 El Primero and the Birth, Death, and Resurrection of Zenith” and subscribe now!

Leave a Reply