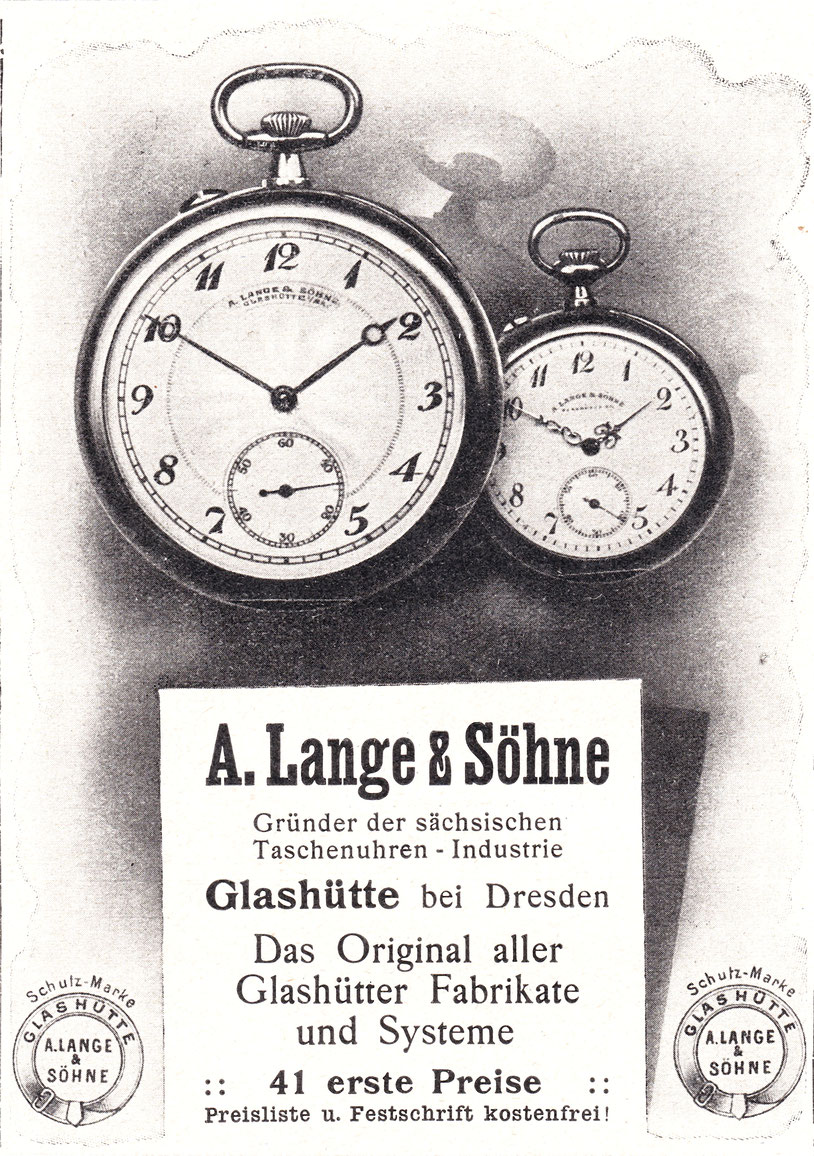

On October 24, 1994, Walter Lange introduced the first watches to bear the A. Lange & Söhne name in nearly 50 years. Once the top name in complicated pocket watches, the famous Glashütte watch brand was destroyed by allied bombs on the last day of the war in Europe and disappeared behind the iron curtain. Now, with the help of Günter Blümlein and IWC, A. Lange & Söhne has returned to its place at the height of the watch market. But there is also a darker time in the Lange story that has not widely been told.

F. A. Lange in Saxon Switzerland

Ferdinand Adolf Lange was born on February 18, 1815 in Dresden. This was the capitol of the Kingdom of Saxony which was just admitted to the German Confederation that same year. The son of a gunsmith, Lange studied watchmaking under Johann Christian Friedrich Gutkäs, the Saxon royal watchmaker. After his apprenticeship, Lange went to work for Joseph Thaddäus Winnerl, himself a student of Abraham-Louis Breguet.

After three years working in Paris, Lange returned to Dresden and married Gutkäs’ daughter, partnering with his former teacher as Lange & Gutkäs. Lange’s experience had shown him the potential of a system of etablissage, with specialized workers producing various components on a large scale. He applied for funding from the state government to begin a watchmaking apprenticeship program and was granted a large loan of 6,700 Thalers.

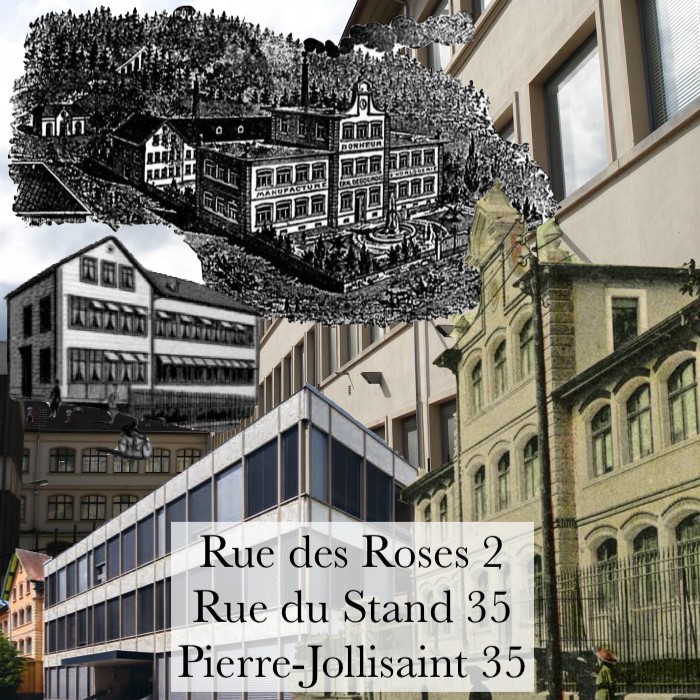

The government wanted to establish a watchmaking industry similar to that in the Swiss Jura to provide employment in the remote mountain towns of Saxony. This region was already known as “Saxon Switzerland” due to its similarity to the Jura, and had seen an influx of ethnic German farmers over the previous 100 years. The tiny valley town of Glashütte was selected for Lange’s workshop.

Lange established an apprenticeship program for his students in the attic of a large house in town. 15 former straw weavers became watchmakers, paying for their training with a loan against the Saxony state funds. Once they were fully trained and had paid off their debt, these watchmakers would establish their own independent workshops, turning out whichever component they were best at producing. In this way, Lange seeded the watchmakers of Glashütte just as Daniel JeanRichard had in Le Locle a century earlier.

Lange was a champion of quality, standardizing on the Metric system and Antoine LeCoultre’s Millionomètre. He also implemented a so-called “3/4 plate” and this would become a symbol for Glashütte watchmaking. Although harder to construct, the use of a large plate instead of individual bridges stabilized the wheel train and improved the reliability of Lange’s watches.

The products of F. A. Lange & Cie. quickly gained international recognition. They earned a medal at the London Industrial Exhibition in 1868 tanks to Lange’s innovative “Glashütte anchor” design. Soon, Lange was exporting components to the United States as well, providing much-needed income in Glashütte but designated there as coming from the better-known city of Dresden.

In 1868, F. A. Lange was joined by his son Richard, and the company was renamed A. Lange & Söhne. As the father turned more to politics and civics (he was mayor of Glashütte from 1848 to 1866 and a member of the Saxon state parliament after this) the son took over management and development. Friedrich Emil Lange also joined the firm, shortly before his father died unexpectedly on December 3, 1875.

Richard Lange was a gifted watchmaker as well, and contributed many inventions to the firm. Among these was dead-beat seconds, a power reserve indicator (marked “Ab” and “Auf” as on modern watches from the company), Rattrapante chronograph, and even an automatic winding mechanism. But Richard Lange was forced to withdraw from the company in 1887 for health reasons, leaving his brother Emil to run it. Richard continued to develop new watch technologies and would become chairman of the German Watchmaking school in 1891.

The Lange family established a pension for their workers by 1870, an unusual show of social responsibility for the time. Using his own funds as well as company shares, the Friedrich Emil Lange Foundation would grow to over 50,000 Marks by the time he left the company in 1919.

A. Lange & Söhne began producing naval chronometers in 1896, with a separate department established the following year. This would be a major new product for the company, and would set the stage for the military contracts that would doom the company 50 years later.

Continued success for A. Lange & Söhne lead the company to expand the factory in 1898. The company’s products were now available across Europe and the United States, with awards and patents rolling in. In just 50 years, A. Lange & Söhne and Glashütte had realized F. A. Lange’s dream of producing the finest watches in the world.

Image: A. Lange & Söhne

Perhaps the ultimate product of A. Lange & Söhne in this period was the remarkable grande complication Ref. 42500, delivered in 1902. It included a perpetual calendar with moon phase display, Rattrapante chronograph with foudroyante, and minute repeater with petite and grande sonnerie. Sold for 5,600 Marks in 1902, it was thought lost until it was recovered in 2001 in poor condition. It was restored by a team of five watchmakers, requiring over 5,000 hours of work, and served as inspiration for a 2013 Grand Complication wristwatch.

Otto Lange took over management of the firm in 1902, the third generation of family ownership. Emil Lange died on October 9, 1921, leaving his sons Otto, Rudolf, and Ger Gerhard to own the historic company.

The Dark End of A. Lange & Söhne

In 1914, A. Lange & Söhne was the producer of the finest watches available. One year later, everything fell apart.

Germany’s entry into the First World War after July 28, 1914 was not a boon for A. Lange & Söhne. The company was known for expensive and complicated watches for gentlemen and ladies in precious metal cases. But the war changed everything.

Germany conducted a fundraising effort to collect gold to pay for the war, and many individuals donated their gold watch cases in exchange for iron replacements, medals, and recognition. The use of a gold watch was no longer socially acceptable, let alone the purchase of one. The war also triggered rampant inflation and shortages of coins. The government issued paper money and encouraged large employers like A. Lange & Söhne to issue their own “emergency money” for local use by employees. In just five years, Emil Lange’s pension endowment would not have paid for a single loaf of bread! Unemployment in Glashütte reached 85% in 1926, and the watch industry was no longer able to support the town. A ruinous flood on July 9, 1927 made things even worse.

A. Lange & Söhne created a lower-priced mass-market brand, OLIW (Original Lange Internationales Werk) in 1925 to try to boost production. It used conventional bridges rather than the 3/4 plate, though they were designed to look similar, and had a Swiss-style pallet fork as well. A steel case was offered, along with silver and gold.

World War I also caused a change in fashion, with men considering the purchase of a wrist watch like soldiers and “fliegers.” A. Lange & Söhne was not prepared for this shift, and had no appropriate movement design for a wristwatch. For the first time, the company was forced to source movements from other companies, including Uhrenfabrik Glashütte AG (UFAG) and the Swiss companies, Niton and Altus. This required setting up a subsidiary in Geneva in 1927 to procure and produce A. Lange & Söhne branded wristwatches. The company was able to use their ladies movement in some wristwatches, but had to turn to Uhren-Rohwerke-Fabrik Glashütte AG (UROFA) for smaller watch movements. These were modified and signed A. Lange & Söhne but were produced by this cross-town upstart.

Production of OLIW pocket watches and outsourced wristwatches was sufficient to keep Lange in business, but output and employment was drastically reduced, especially after the stock market crash of 1929. By the following year, as few as 40 people were still employed by A. Lange & Söhne, with many moving to the stronger Glashütte firms of UROFA and UFAG.

Credit: GlashuetteUhren.de

As the Nazis came to power, A. Lange & Söhne saw an opportunity to supply the German military with watches and timers. After a 1933 inspection by the new regime, various Glashütte companies were selected for military contracts, with A. Lange & Söhne building pocket watches and marine chronometers. It was good for the company that there was a military market, since by 1942 the Reich made it illegal to produce non-military products like ladies watches!

On September 14, 1940, 30 French prisoners of war arrived at a forced labor camp in Glashütte. Over the next three years, forced labor became more and more common in the town, especially as more of the German population was conscripted into the military. Called “foreign workers” by officials, these prison camps grew across Germany, with as many as 3,000 in Glashütte by 1943 perhaps outnumbering the residents. It is well-documented that these workers were mistreated, poorly fed, and forced to work in the local factories against their will.

A. Lange & Söhne was one of the beneficiaries of forced labor, employing prisoners to build chronometers, timers, and fuses for munitions. Many of these workers were from other European countries (Russia, Ukraine, Czech, France) and a majority were women. According to a 1946 accounting of labor by A. Lange & Söhne, many spent years working in the factory and living in the labor camp. Other documents show that some worked 12 hour days and suffered or died in the town. Some are buried un-named in the town. With more prisoners than residents, it is likely that most of the factories in Glashütte relied on forced labor during the war.

Credit: GlashuetteUhren.de

The Russian army was approaching Glashütte in April of 1945 as the war was nearing its end. After the fall of Berlin and suicide of Hitler, representatives of the German military signed a document of total and unconditional surrender on May 7, 1945. Amid the chaos of the next 24 hours, Russian fighter-bombers attacked a retreating German army column in Glashütte early in the morning on May 8. This attack destroyed the A. Lange & Söhne factory and damaged many other buildings in the town.

The town of Glashütte was occupied by the Soviet army after the war, and the surviving watchmaking machinery was seized. Much of the A. Lange & Söhne equipment was destroyed, but what remained was sent to Moscow as reparations for the war.

The company was nationalized as Mechanik Lange & Söhne VEB on April 23, 1948 and work resumed on precision watchmaking in Glashütte. There was even an attempt to market these watches under the name of Lange & Söhne internationally, but the effort was unsuccessful. On July 1, 1951, Mechanik Glashütter Uhrenbetriebe (GUB) absorbed Lange & Söhne, marking the end of the original company.

Lange Uhren and Les Manufactures Horologères

When Rudolf Lange’s son Walter was born in Dresden in 1924, the family business was in chaos. Inflation and unemployment was rampant, and no one was buying expensive German watches. Still, he encouraged his son to train as a watchmaker, hoping he would someday take over A. Lange & Söhne. But that dream would not be realized for six decades!

Walter Lange graduated his apprenticeship in Austria in 1942 and was immediately conscripted into the German army. He was badly injured on the Russian front in 1945 and traveled an arduous path back home. Lange arrived in Glashütte on May 7, 1945, the last day of the war, and witnessed the Russian bombing of the A. Lange & Söhne factory early the next morning.

After Lange & Söhne was expropriated by the communist government, Walter Lange was assigned to become a uranium miner. Seeing this to be a certain death sentence, he fled to West Germany. With his brother, Ferdinand Adolf Lange, Walter tried to set up a watch company in Pforzheim under the name “Original Lange Uhr” but was unsuccessful. Still, he dreamed of re-starting the company.

When Germany was reunified in 1990, the nation created an agency to privatize state-owned businesses. The Treuhandanstalt offered Glashütte’s watchmaking enterprise to Hartmut Knothe, who had grown up in the town and worked at the factory. At the same time, Walter Lange approached him to help re-establish A. Lange & Söhne in Glashütte. Knothe decided that the brand had more potential than the factory and joined the famous firm. On December 7, 1990, Lange Uhren GmbH was incorporated, 145 years to the day after F. A. Lange established his company in Glashütte.

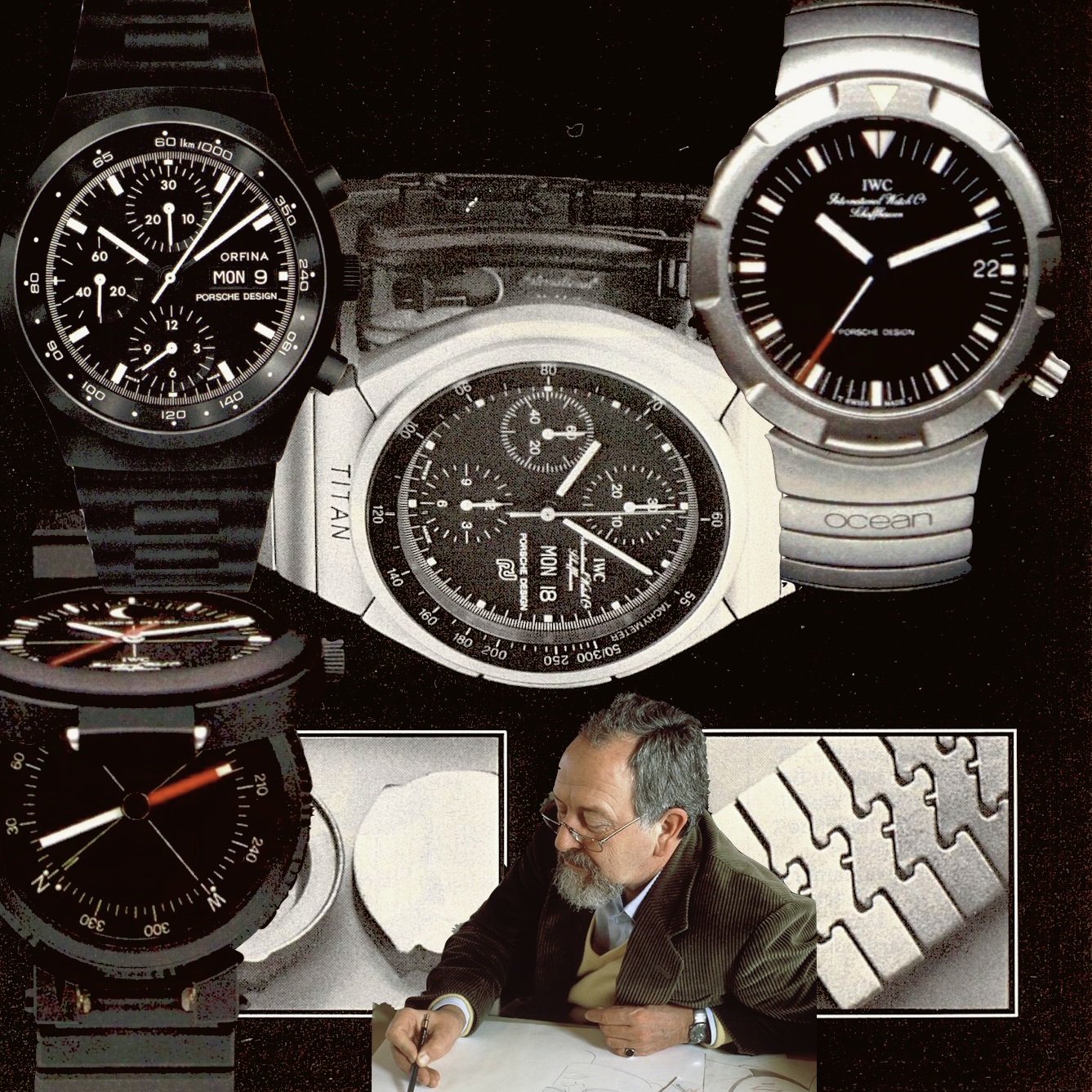

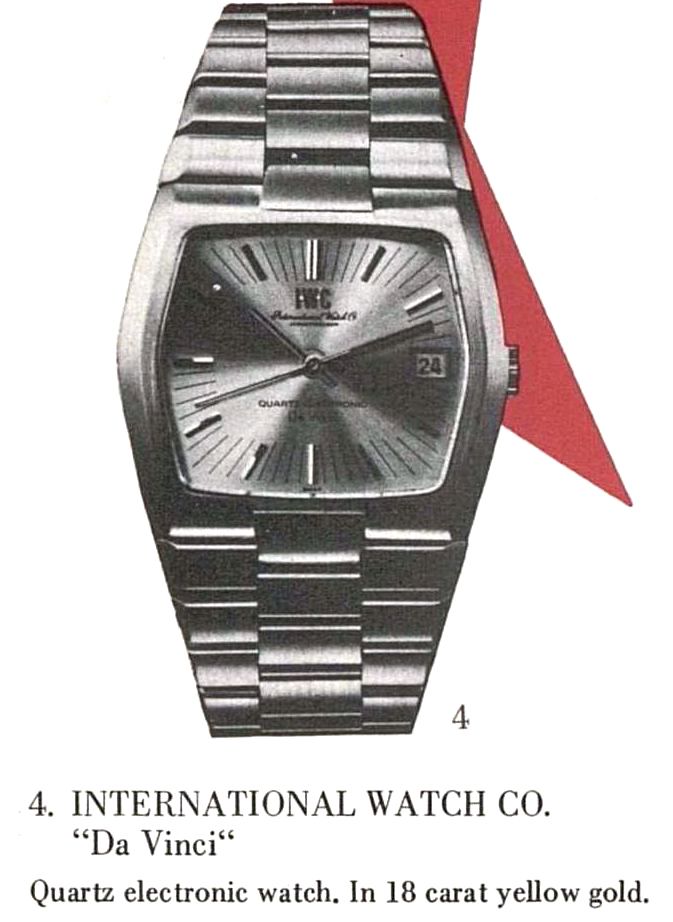

Walter Lange’s connections with the Swiss watch industry had finally paid off. His friend Günter Blümlein was head of IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre within German industrial giant VDO, and saw the same opportunity as Lange and Knothe. He offered financing on behalf of IWC as well as a development partnership for a new line of A. Lange & Söhne watches. But most importantly, Blümlein brought guidance to establish and re-develop the famous watch brand.

On October 24, 1994, Lange, Blümlein, and author and watch seller Martin Huber introduced the four watches that would make up the new A. Lange & Söhne brand:

- The Saxonia was an understated dress watch with a “big date” complication recalling the digital clock built in the Dresden opera house by F. A. Lange’s teacher, JCF Gutkäs

- The Arkade was designed for women and had a novel square-sided case designed to reflect the arcades of the Dresden castle courtyard

- The Lange 1 boasted a novel dial design, with off-center hour and minutes dial, small seconds, a power reserve indicator, and Lange’s big date

- The Tourbillon “Pour le Mérite” was the first watch to combine a tourbillon and fusée-and-chain constant force power delivery system

Each watch in the new A. Lange & Söhne range boasted an in-house movement, a novel yet classic design, and impeccable finishing. The clean bezels, classic dials, and “Alpha” hands were unlike anything else on the market. And the return of classic Glashütte elements like the 3/4 plate, gold chatons, and swan neck regulator were enthusiastically embraced.

The launch was a masterpiece, perfectly timed as the market opened to mechanical watchmaking and embraced the resurgent unified Germany. Although the A. Lange & Söhne name was not well known by the general public, the brand retained a strong attraction for watch enthusiasts.

It is telling that Lange and Blümlein invited Martin Huber to join them in introducing the new A. Lange & Söhne line. Andreas Huber established a watch shop in Munich in 1856 and the family name became synonymous with fine watches in Germany. Martin Huber took over the family business in 1966 at just 25 years old and soon established his reputation as a historian of horology as well. His books on Patek Philippe and A. Lange & Söhne are considered standard references for the historic brands, and he was brought in to consult with the new company as it was developing this new four-watch line. Huber, Blümlein, and Lange gave unparalleled legitimacy to the re-born A. Lange & Söhne.

Although the Saxonia and Arkade were impressive, it was the Lange 1 and Tourbillon that established the watchmaking bona fides of A. Lange & Söhne. The Lange 1 was unlike any other watch available at the time, with the highly unusual asymmetric dial standing out in a growing field of new complicated watches. Although offset from the center, all of the elements are harmoniously placed on the dial: The pivots of the time and power hands align perfectly at the middle of the watch and are placed at 1/3 the way across the dial; the small seconds and date frame are similarly balanced with the power reserve pivot on the crown side at 1/4 intervals; even the Roman numerals and the text are placed harmoniously on the dial. Of all the original Lange offerings, it is the Lange 1 that would become the symbol of the brand.

The tourbillon was symbolic of the resurgence of mechanical watchmaking in the 1990s, and it was important that A. Lange & Söhne offer a novel twist. Audemars Piguet had produced the first tourbillon wristwatch in 1986, and Blancpain had used the complication as their calling card a few years later. by 1994, many high-end brands and independent watchmakers offered a tourbillon, but none had ever incorporated a constant force mechanism. The fusée-and-chain and planetary transmission used by A. Lange & Söhne recalled some of the designs of F. A. Lange and stood apart in this corner of the market. And the prospect of an complicated hand-made watch promised that this new A. Lange & Söhne would be a true successor to the original and not just a branding exercise for IWC. It was named “Pour le Mérite” after a historic German order of merit, ironically established by Frederick II, king of Prussia, Saxony’s historic rival.

A. Lange & Söhne would be tremendously successful in the 1990s, thanks in large part to the contribution of Blümlein and his luxury watch expertise. Les Manufactures Horologères (LMH) was created inside VDO in 1991, including IWC and 60% of Jaeger-LeCoultre. When VDO was acquired by Mannesmann that year, it provided financial support and stability to grow all three brands. Through IWC, LMH would acquire a majority stake in A. Lange & Söhne by the time it launched in 1994, and this would grow to 90% by the end of the decade, with the Lange family retaining 10%.

Image: A. Lange & Söhne

When Vodafone acquired Mannesmann in 1999, the company offered the watchmaking assets for sale. A bidding war ensued, with PPR and LVMH actively seeking to acquire the three luxury watchmakers. But Richemont quietly approached Audemars Piguet for the right to buy the 40% of Jaeger-LeCoultre it still held if they were successful in acquiring the rest. On July 21, 2000, this deal was announced, with Richemont paying CHF 2.8 billion for A. Lange & Söhne, IWC, and Jaeger-LeCoultre. The brands joined Cartier, Vacheron Constantin, Panerai, Piaget, Baume & Mercier, and Montblanc.

Walter Lange won the Special Jury Prize at the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève in 2014 and passed away on January 17, 2017. He was remembered with fondness by many in the industry.

The Past and Future of A. Lange & Söhne

Today, A. Lange & Söhne is once again one of the most prestigious watchmakers. It is often counted alongside Audemars Piguet and Patek Philippe as “the new holy trinity of haute horology.” These three brands are so successful that they have recently implemented drastic sales controls on their most desirable models, with long waiting lists for the Datograph, Lange 1, and new Odysseus. Signature models like these, as well as the Zeitwerk and four more “Pour le Mérite” models truly live up to the reputation of F. A. Lange and his heirs.

Watch enthusiasts are lucky that the A. Lange & Söhne story did not end with World War II, but we must remember what happened at that time. Assuming my research is accurate, the company’s use of forced labor is particularly upsetting. Walter Lange and Richemont bear no responsibility for this crime, but it is disappointing that the modern A. Lange & Söhne has not done more to acknowledge these actions of the historic namesake firm. Many other German companies have admitted their actions during the war and sought to make amends or offer reparations. Although today’s A. Lange & Söhne behaves admirably in supporting many social and environmental causes, this element of the company’s history is conspicuously absent in their account.

The modern firm of A. Lange & Söhne is firmly rooted in its history and tries to build on the legacy of the former company. From the “big date” to the swan neck regulator to the 3/4 plate, it is thoroughly connected to Saxony. And the company makes frequent references to F. A. Lange and members of the founding family, including naming their complicated chronometer line for Richard Lange. Anniversaries are also an important element for the company, with many important models launched on auspicious dates and years. Given this fervent celebration of the past, it is only appropriate that the modern company acknowledge the former’s actions during the war and try to make things right.

References

- Most of the historic images, including the document regarding forced labor, come from GlashuetteUhren.de

- Postcard from Glashütte, Europa Star, 2011

- The Glashütte Legend is Revived, Europa Star 208, 1994

Leave a Reply