What was the first automatic watch? English inventor John Harwood certainly deserves credit, and his unusual design was produced in some volume by A. Schild, Fortis, and Blancpain starting in 1926. And Leon Leroy produced a few “perpetual” watches a few years earlier. But one watch that stands out among the many self-winding watches released following the expiration of Harwood’s patent in 1931: Eugène Meylan’s automatic winding module, produced in volume by Glycine and Pretto, was the first practical and widely-produced automatic winding mechanism. And the man behind it has a fascinating story of invention, entrepreneurialism, and dedication with a truly heartbreaking ending.

This article accompanies Episode 7 of The Watch Files, a podcast from Europa Star and Grail Watch. Listen to “07 Eugène Meylan Should Be Remembered For Glycine’s Automatic Watch” and subscribe now!

If you’re interested in learning more about Glycine, including details on the Airman and later models, check out the wonderful Glycintennial site created by Emre Kiris!

Eugène Meylan and La Glycine

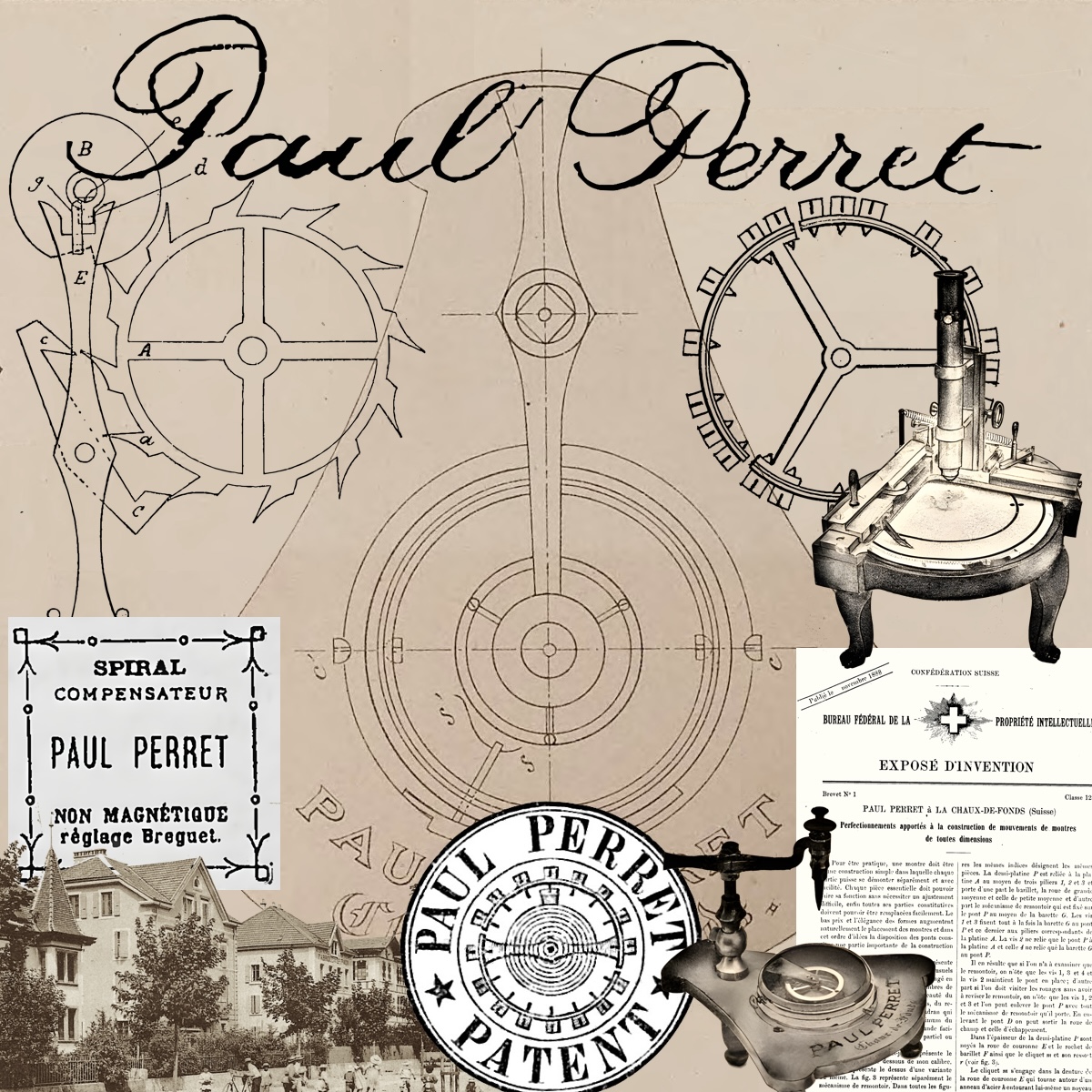

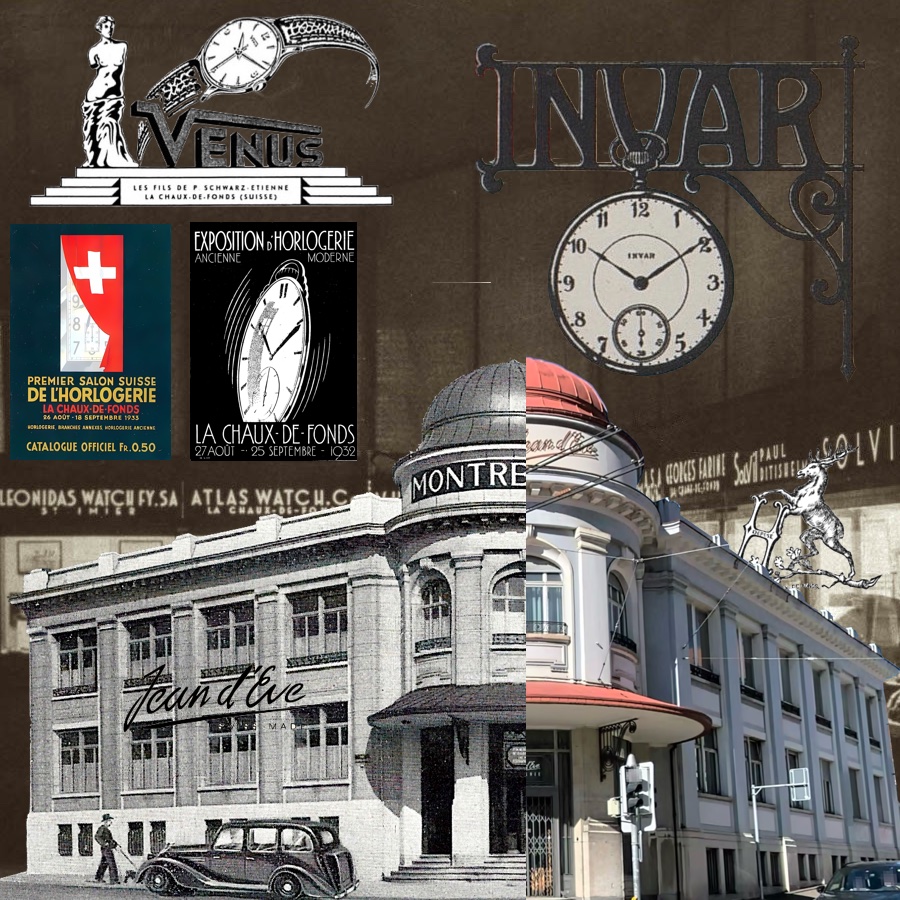

Arthur Louis Eugène Meylan was born on October 17, 1891 in Le Chenit in the Vallée de Joux, home of Jaeger-LeCoultre (in Le Sentier), Audemars Piguet (in Le Brassus) and many other well-known watchmakers. He attended the watchmaking school in La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1910 and 1911, just as mass production of watches was on the rise. He must have been a gifted student, as he is listed as receiving a “1st Class tres satisfaction” for one of his watches submitted in 1911 to the Bureau Officiel de La Chaux-de-Fonds Pour Le Contrôle de la Marche des Montres. This is the first of many accomplishments for the young Meylan!

Shortly after graduation, Meylan left La Chaux-de-Fonds to settle in the city emerging as a hot-spot of industrialized watchmaking. Situated on the “Röstigraben“ where French and German Switzerland meet, the home of Omega and Rolex is known as Bienne in French and Biel in German. Since Meylan’s birthplace was along the border with France, we shall call it Bienne, as he most certainly did as well.

As watchmaking was industrializing and expanding, many companies were relocating to Bienne/Biel. The city had abundant buildable land and a large population capable of working in factories. But the textile bust of the 1880s left the city hungry for new opportunities. The town fathers offered incentives for watchmakers to relocate from the Jura and La Chaux-de-Fonds, and many answered the call.

The rapid industrialization of the city caused labor unrest, but watchmakers were following the lead of Louis Brandt’s sons, who had grown the Omega factory there to house over 600 workers. A short distance from the Omega factory was an expanse of flat land near a bend in the Suze river known as La Champagne, and this would become the home to many watchmakers in the early part of the 20th century.

On May 20, 1914, Eugène Meylan registered his own watchmaking company in Bienne. He named it La Glycine, likely derived from the purple wisteria flower, which is called Glycine in French. This dainty name was paired with an exuberant typeface that suited his product line: Compact and ornamented watches suitable for a respectable woman. Within the year he submitted a number of watch and movement designs and began production.

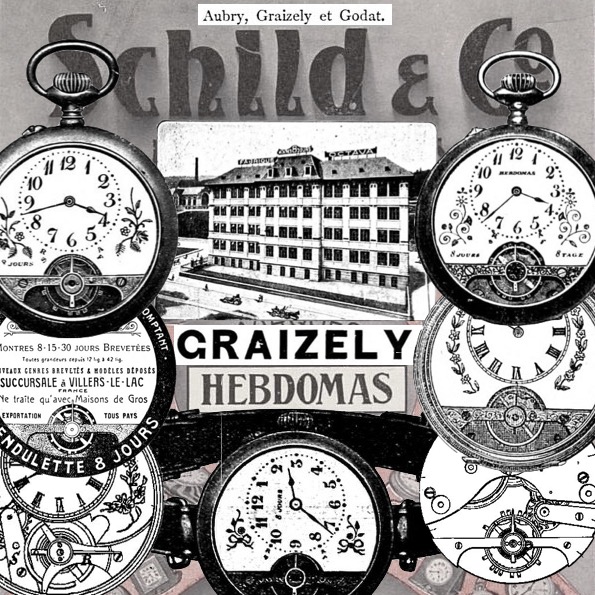

Meylan selected a new villa in La Champagne, number 1a, situated along a historic lane known as Chemin de la Champagne that would soon give way to strict perpendicular blocks as the city developed. This large factory provided him space to produce a series of compact movements of his own design. Measuring 8.75, 9, and 9.75 ligne, these would be ideal movements for the popular new ladies wrist watch craze of that decade.

Meylan must have been an aggressive businessman, starting a large watch manufacturer in 1914 at just 23 years of age, and this entrepreneurialism continued through the early part of his life. Although he is deeply associated with Glycine, Eugène Meylan was only involved in the company for a short time. Watchmakers Piccola and Joffrette (also spelled Jofrette) became became co-owners of La Glycine on November 4, 1916, with the official name of the company now Fabrique d’Horlogerie La Glycine, Piccola et Joffrette. Meylan’s name was no longer associated with the company’s official filings, and it is not clear how involved he was after this.

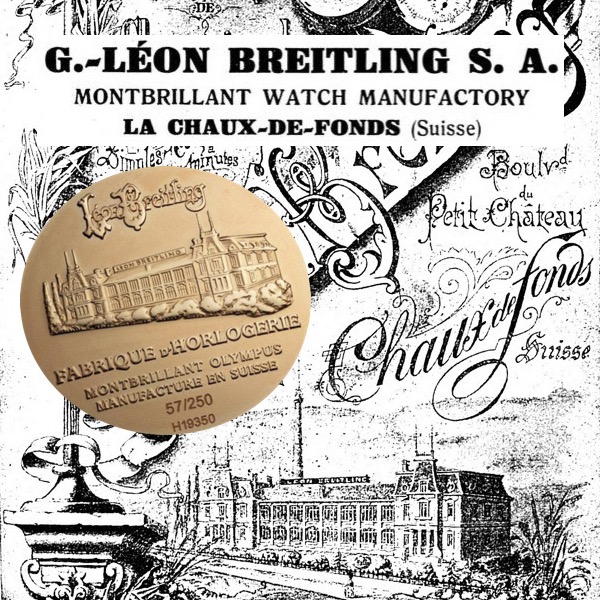

After the Great War, Meylan turned his attention back to La Chaux-de-Fonds. He connected where with Henri Jeanneret of Le Locle to start a new firm. Meylan & Jeanneret would become known as Fabrique Silene in 1918 and would spawn two more brands in 1919: Sonex and Darax. The most notable thing about these companies was their address: Meylan & Jeanneret leased space in 1918 in the Montbrillant Watch Manufactory in La Chaux-de-Fonds, the same building that housed Breitling for a century!

A 1920 advertisement does show some information about Meylan and Jeanneret’s Darax SA. We see that Darax produced complete watches using 7.75 to 10.5 ligne anchor movements. The “Montres Fantaisies Rondes, Or Argent” (“round fantasy watches in gold and silver”) suggests that this was a higher-end company producing decorative watches for ladies.

During this time, La Glycine focused on small form and round movements and was quick to offer a line of wristwatches. These were sold with a logo featuring two flags and the initials “L G” for “La Glycine” and period advertisements boasted of their “best equipped factory from a technical and mechanical perspective.” La Glycine also produced other fine steel products, including a staple to join the ends of a transmission belt!

One key to the success of La Glycine in the early part of the century was the company’s focus on interchangeability of components. Indeed, La Glycine stands apart in period advertisements by showing the well-equipped parts supply boxes available to watchmakers and resellers.

Ferdinand Engel Acquires Glycine

Like many in the Swiss watch industry, Eugène Meylan’s companies found themselves to be over-extended in the 1920s. The first World War drove massive expansion of watch production in Switzerland, and this lead to cutthroat competition by 1920. In 1921, exports dropped by half and mid-sized watch manufacturers were unable to turn a profit. Many were forced into bankruptcy.

This trend reached Meylan, Piccola, and Joffrette in 1922, and La Glycine was taken over by two local businessmen. Ferdinand Engel was a local watchmaker originally from Eggiwil and Georges Flury produced watch balances at his workshop in Les Breuleux in the Jura near France but was originally from Mümliswil in Solothurn. This takeover must have happened during 1922, since Engel and Flury signed a New Years ad in the December 28, 1922 edition of La Fédération Horlogère with no mention of Meylan, Piccola, or Joffrette.

Six months later, on July 6 1923, the names of Piccola & Jofrette were officially removed from the company. From this point, the company was known simply as Fabrique d’Horlogerie La Glycine. In addition to Engel and Flury, management of La Glycine included Charles Perret, a banker from the village of Renan, a short distance from Flury’s workshop. This must have been a challenging time for Meylan, as his joint ventures with Henri Jeanneret, Sonex and Darax, would face bankruptcy starting in February 1924.

La Glycine flourished in the 1920s under the leadership of Ferdinand Engel, and he would guide the company for two decades. As seen in their ads from the period, Glycine continued to be a leader in compact movements, especially so-called form movements that fit the rectangular shaped cases popular at that time. The company offered popular novelties, including the travel alarm clock and was part of the “guichet” (“window”) watch craze of 1931 with their own patented design. And Engel established strong export sales, producing tri-lingual advertisements in German and English, a novelty at that time.

Very little is heard from Eugène Meylan for the next few years, though he was quite involved in civic projects, recognizing soldiers who fought in World War I and presiding over a committee to build a monument to them in La Chaux-de-Fonds. Meylan started a new firm called Fabrique de Sertissages “Precis” in 1926. The name suggests that it was focused on gem setting (“sertissage” in watchmaking) and a 1927 ad shows the company working with other local firms. But this venture would fail in 1932, with the workshop and furnishings put up for sale in June.

It appears that Meylan also produced whole watches, with a few examples signed “Eugène Meylan La Chaux-de-Fonds” from this period now known. These were likely not produced at the Precis sertissage workshop at Rue Jacob-Brandt 61, but little else is known about them. He became the representative for the French Electric Bulle Clock by 1928, operating out of the same address. Meylan would purchase a watch reselling business in Berne known as Chronomuri in 1931 but this business too would fail in 1934.

The impact of the 1929 stock market crash in the United States was slower to reach Switzerland than other countries, but it posed a challenge for watchmakers dependent on exports. As the Nazis rose to power Germany, their nationalist propaganda emphasized domestic production. This made it difficult for Swiss companies to sell there, with domestic brands rising to prominence, notably Zentra (which used Tavannes and Minerva movements) and Alpina. Sensing an opportunity, Glycine partnered with Doxa (of Le Locle) and Meyer & Stüdeli (who produced Roamer and Medana brand watches in Soleure) to create a joint venture based in Berlin known as Medex. This arrangement was so successful that these brands enjoyed continued success there for decades after World War II.

Once the Great Depression reached Switzerland, watchmakers were forced to drastically reduce production. Exports dropped again, from over 260 million francs in 1928 to just 71 million in 1932. Many watch producers failed at this time, and the economy of cities like Bienne, La Chaux-de-Fonds, and Le Locle was particularly hard hit. Yet new technological advances, and a looming Second World War, would soon create a new market for Swiss watches.

Eugène Meylan’s Automatic Watch

As much an inventor as an entrepreneur, Eugène Meylan saw John Harwood’s automatic winding watch concepts of the late 1920s as an opportunity. Even as Fortis and Blancpain struggled to bring Harwood’s watch to market in volume (along with an earlier prototype from Leon Leroy), many others worked on alternative automatic winding designs. Very few of these had any success at all, but a few did make it to market around 1931: Emil Frey’s Perpetual Watch Co., Leon Hatot’s Rolls (also produced by Blancpain), Champagne Watch Co., Wyler, and of course Aegler’s Rolex Perpetual.

But the most successful early automatic winding watch movement was the brainchild of our own Eugène Meylan! A series of patents filed by Meylan starting on October 15, 1930 show the progression of the module that would put self-winding watches in the hands of the masses for the first time.

Seeing the potential for this new design, Meylan established a new company to license and exploit his invention. It was called Automatic E.M.S.A. for “Eugène Meylan Société Anonyme.” Meylan applied for a pair of patents on October 15 and 24, 1930 and registered the creation of Automatic E.M.S.A. on June 9, 1931. The company registration noted the application numbers (77588 and 77878) and these would become patents CH149137 and CH149138 in August 1931. This pair of key patents were transferred to Automatic E.M.S.A. on September 23, 1931.

Unusually, Meylan’s design was a separate module that could be paired with nearly any 8.75 ligne watch movement. An oscillating weight segment was anchored at the center and would swing through a partial arc, cranking the barrel of the movement through a series of gears. Because the base movement was so small, the combination was still a usable 26 mm diameter and 5.70 mm thick.

Dr. Ranftt notes that Meylan developed a novel system to prevent over-winding of the barrel: A Geneva stopwork transfers excess energy back to the oscillating weight through a spring rather than over-torquing the mainspring. He also identifies the notches provided to allow movements other than the Venus 60-II he encountered.

Automatic E.M.S.A. versus Glycine and Pretto

It seems clear that Eugène Meylan contacted his old friends at Glycine about producing a watch using his novel automatic module and they jumped at the opportunity. Just a few months after the patent was granted, Glycine was offering an automatic watch featuring his invention. The advertisement shown above came in the August 19, 1931 edition of La Fédération Horlogère and depicts a complete watch, likely using Glycine’s own Cal. 19 or Cal. 20 along with a module clearly marked “E.M.S.A. Patent.” Given the number of period Glycine Automatic watches that survive to this day, it seems likely that production and sales were quite strong for a number of years.

Georges Flury and Ferdinand Engel had registered a second company, Pretty Watch Co., in 1924 and had operated that firm, renamed Pretto on October 31, 1927, as a sister company to Glycine. Pretty/Pretto specialized in gem setting, engraving, and other aspects of watchmaking, and it was Pretto that licensed the design of the Automatic E.M.S.A. module and constructed it for use by Glycine. But the two firms were closely linked, and soon Ferdinand Engel and his sons Lous-Paul and Vital-Robert Engel would take over both. Georges Flury and Charles Perret would be removed from the administration of Glycine and Pretto on the same day, March 28, 1933.

As mentioned, Bienne/Biel sits at the crossroads of French-speaking and German-speaking Switzerland, and Meylan’s invention would soon be pulled from both directions. Two aggressive businessmen, Robert Müller of Zürich and Georges Henry of Geneva, spent 1933 fighting over the rights to Meylan’s design.

Eugène Meylan sold Automatic E.M.S.A. to Robert Müller, founder of Mulco, at the end of 1931

Robert Müller had recently taken over movement finishing firm Mühlmatter & Grimm and spent 1931 launching a watch brand based on his own name. Mulco would need a differentiator in the crowded watch market, and self-winding technology was an exciting prospect. On December 8, 1931, Eugène Meylan sold Automatic E.M.S.A. to Müller, just a month after the launch of Mulco.

Georges Henry was an aggressive businessman and was looking to build a watchmaking empire. He took over the patents of Geneva watchmaker Beaulieu on its failure in 1923 and built his own brand, Nanda, starting in 1925. Two years later, Henry and Paul Cattin registered Gigantic, and this would be the family’s primary company for decades. But it was Henry’s ILO S.A. (also called Ilosa) that claimed an exclusive license to produce modules based on the Automatic E.M.S.A. design in 1931.

Glycine Watch Co. and Pretto Watch Co., in Biel, two buyers of the said devices, do not benefit from any rights to manufacture them, contrary to the announcement that the latter has placed in this newspaper. The competent courts will have the case.

This manufacturing right has been contracted in due form to Pretto Watch Co. S.A. Biel. No judgment has been made to remove the manufacturing right from Georges Henry or from Pretto Watch Co. The latter alone has the manufacturing right.

In addition, Glycine Watch Factory and Pretto Watch Co. S.A. advise that they are the sole dealers for the sale of Automatic E.M.S.A. for the whole world, and that any person seeking to destroy this right of sale in any form whatsoever, will be prosecuted legally.

On March 22, 1933, Engel and Henry (as Pretto and Ilosa) put Müller’s Automatic E.M.S.A. on notice that they would not share Meylan’s invention. An announcement in La Fédération Horlogère promises that Pretto would take legal action against anyone manufacturing a watch based on the Automatic E.M.S.A. patent, since they have a sole license from Georges Henry.

Müller replied a week later with a similar notice in the same paper. He claimed that Glycine and Pretto were simply “buyers of said device” and did not have any right to manufacture it. Clearly there was a serious misunderstanding about the rights Müller had purchased!

Henry and Engel fired back on May 31, claiming not just manufacturing rights but also sole right to worldwide sales of the device! This “open letter” opens with Georges Henry claiming to be “sole owner of the exclusive right to manufacture” the self-winding device. Then we see Ferdinand Engel joining in the name of Glycine and Pretto to claim sole worldwide rights. Interestingly, Eugène Meylan is nowhere to be seen in the spat.

It is not clear what happened next, or if there was any further action. But this scandal would certainly put a damper on any licensing efforts by either Müller or Henry beyond Engel’s Glycine/Pretto. We know that Ilosa declared bankruptcy on February 13, 1934, however. The Great Depression certainly had an impact on Georges Henry in Geneva, but perhaps he no longer saw the fight as a viable one. With Henry out of the picture, and Automatic E.M.S.A. down to its last thousand francs by the end of 1933, Glycine and Pretto must have come to an agreement with Müller.

The battle between Zürich and Geneva was finished, with Biel/Bienne left in the middle. On August 23, 1935, a notary declared that the key patents (CH149137 and CH149138/157572/157573) were the property of La Glycine, and this was officially registered on August 27. Glycine continued to produce and sell Meylan’s automatic winding device for over a decade. Müller’s family would run Mulco until 1995, and Georges Henry’s re-financing allowed Gigantic to last through 1990, with both companies seeing success in the 1950s. But neither would see the same success as Engel and Glycine!

Further Developments of the Glycine Automatic

Because the Automatic E.M.S.A winder operated directly on the barrel, it did not interact with the keyless works for the crown at all. This meant that some watches needed their works modified slightly to keep from interfering with the winder, and thus their hand winding capability was no longer used. It also offered another opportunity for the inventive Glycine to change the look and feel of a watch.

Harwood’s automatic watches lacked a crown at all, using a rotating bezel to set the time. Glycine invented a folding crown that could tuck out of the way when not in use, streamlining the watch. Although not sealed like a Rolex Oyster Perpetual, this improved water resistance and helped resist shocks. This patent was issued in 1932 but was deleted just three years later, so it was certainly not a successful modification.

More successful was the use of various movements with the Automatic winding module. Dr. Ranftt’s example is a Venus movement, but period technical sheets from Glycine show a variety of their movements used with the module. In theory, nearly any 8.75 ligne movement could have been used, but since Glycine was a master of compact movements in the 1930s it is likely that they used their own.

Glycine became part of ASUAG in 1942 (a year after Georges Henry’s Gigantic joined) and this gave the company access to a variety of emerging automatic movements as well as an impetus to use them. This move coincided with the death of Ferdinand Engel near the end of that year. Vital-Robert Engel had become manager of Glycine’s Geneva branch, and he took two board seats on October 22, 1942 after his father’s death. But the company would soon come under new management.

A. Schild and FHF were developing fully-integrated automatic movements, and Eterna would soon launch their advanced Eterna-Matic line. But it was Felsa that was the best fit with Glycine, and the two companies developed the famous bi-directional winding Bidynator in 1947. After this, there was no need to continue using the Automatic E.M.S.A. module, but it gave the company a unique differentiator throughout the 1930s.

Glycine Today

The 1950s and 1960s were a time of innovation and success for Glycine. With their technical capabilities bolstered by ASUAG (and by extension Ebauches SA), Glycine was able to innovate and develop signature models like the 24 hour Airman, the sealed Vacuum, and the design-leading SST models.

After the death of Ferdinand Engel, the company was turned over to Charles Hertig. His Altus Watch Co. would be closer and closer associated with Glycine and the two would merged in 1963. The La Champagne villa proudly wears the names of both companies today. Hertig was also a distributor of other brands, including Junghans, and was active in selling watches and clocks in Spain and Portugal. Hertig was also active in the watchmaking community, representing German interests in ASUAG and the FH.

Glycine saw tremendous success with military and aviation models, and the company is today nearly synonymous with the 24 hour Airman line. They also benefitted from the sports chronograph and space race trends in the 1960s, and their US operations have been a continual strong suit. Starting in 1964, Glycine & Altus sealed their watches in a vacuum chamber, and this became a technical highlight through the following decades. Glycine was even part of the LCD watch revolution in the 1970s as part of the Ditronic consortium with Optel, and I will be writing more about this in the future.

Glycine was “rebooted” by the Brechbuhler family in 1984, who refocused on the historic models for the next few decades. It was taken over by Stephan and Nicole Lack in 2011 and became part of DKSH along with Maurice Lacroix. In 2016, Glycine was sold to the Invicta Watch Group, an American firm that also owns TechnoMarine in addition to the high-volume Invicta brand.

Denouement: The Tragedy of Eugène Meylan

Eugène Meylan was a gifted watchmaker and inventor but lived an unfortunate life. He was forced to sell La Glycine just a few years after founding it, and his venture with Henri Jeanneret was taking shape just as the post-war watch bust took the wind out of the sails of the entire industry in the early 1920s. Meylan shifted to gem setting with Précis during the boom in the later 1920s but this too failed in 1932 with the Depression, as did his second business selling watches as Chronomuri in Berne.

The timing of Meylan’s invention of the automatic watch in 1930 could not have been worse. It is likely that his quick sale of Automatic E.M.S.A. to Robert Müller (just 3 months after transferring his patents there) was driven by the dire state of finances for the entire watch industry in 1933. Meylan’s most successful venture in this period, importing and distributing French “Bulle” clocks, which lasted at least from 1928 through the start of World War II.

After the war, Meylan faced even more difficulties. In 1947 his business activities drew the attention of the authorities, who investigated him on charges of smuggling gold. It is understandable that a dealer in precious metal and gem-set watches would be looked on with suspicion due to the economic challenges faced during the war, but this would have been a great setback even after he was quickly cleared by the Swiss Federal Council.

But the worst came in 1955. Meylan move to Geneva after the war to establish another watch distribution business. He was beaten and robbed there on July 25, with the assailant accusing him of “immoral” activities. In September of 1955, he traveled to Neuchâtel and stopped at the old Worker’s Circle social club there. On the evening of the 23rd, he met an apprentice mechanic, who later reported that Meylan made an “immoral proposal.” At 2 in the morning, at a secluded location called The Mail, the young worker murdered and robbed Meylan. He was 64 years old.

This heartbreaking ending brings the story of Eugène Meylan to a tragic close. Who knows what he could have accomplished if his businesses had been launched at more opportune times? And it is undoubtedly a shame that so many have overlooked Eugène Meylan, watchmaker and entrepreneur, and inventor of the first successful automatic watch!

Additional Reference Materials

My primary sources had a lot of detail to “prove out” this story. Rather than include them “in-line” in the article above, I decided to add them here at the end as additional reference materials. If this works out, I might do the same in the future!

External Links

- Glycintennial – I am indebted especially to Emre Kiris, who has done such wonderful work uncovering the history of Glycine watches and Eugène Meylan!

- Ranfft Pink Pages: Glycine Eugene Meylan

Key Patents

This story includes a confusing array of patents, which I will attempt to untangle here. The key patents are bolded. In reading the various filings, it becomes clear that CH149138 is the basis for both CH157572 and 157573 and that they are linked together.

- CH149137 – “Dispositif de remontage automatique de mouvement d’horlogerie” (the automatic winding mechanism) – Filed by Eugène Meylan on October 15, 1930, registered August 31, 1931, transferred to Automatic E.M.S.A. on September 9, 1931, transferred to Glycine on August 23, 1935

- CH149138 – “Dispositif de remontage automatique pour pièce d’horlogerie” (tied to 572 and 573) – Filed by Eugène Meylan on October 24, 1930, transferred to Automatic E.M.S.A. on September 9, 1931, transferred to Glycine on August 23, 1935

- CH157572 – “Dispositif de remontage automatique pour mouvement d’horlogerie” – Additional Patent by Automatic E.M.S.A. on March 5, 1931, transferred to Glycine on August 23, 1935

- CH157573 – “Dispositif de remontage automatique pour pièces d’horlogerie” – Additional Patent by Automatic E.M.S.A. on July 22, 1931, transferred to Glycine on August 23, 1935

- CH156806 – “Pièce d’Horlogerie” – Filed by Automatic E.M.S.A. on July 24, 1931, announced Deleted on February 26 1936

- CH159200 – “Dispositif de mise à l’heure pour montre à remontage automatique” (the folding lever) – Filed by La Glycine on October 19, 1931, registered December 31, 1932, announced Deleted on August 28, 1935

Vintage Glycine Ads: 1916-1945

Glycine was an aggressive advertiser from Eugène Meylan through Piccola and Joffrette and Ferdinand Engel. This gallery of vintage ads gives a wonderful tour through the products and positioning of the company through World War II.

Meylan & Jeanneret: Sonex and Darax

The corporate story of Meylan & Jeanneret is clear: It was founded by Eugene Meylan and Henri Jeanneret on May 21, 1917, used the Silene brand from October 28, 1918, and produced watches with at least 7 ligne movements. Sonex SA was registered on January 27, 1919 and Darax SA on September 9, 1919 and the firm was headquartered at Montbrillant 1 (the former Couleru-Meuri and Rode Watch Factory, the same building as Breitling). The decline of the two firms happened at the same time in 1924, with the final failure on November 14. Sonex was closed on September 28, 1925 and Darax on October 1, 1925.

Although there is no concrete link between Sonex and Darax, the circumstances (the same address and multiple coincidences of date) not to mention the names suggest that the firms are related. And we know for sure that Sonex was a “reprise” (resumption) of the business of Meylan & Jeanneret’s Silene. So I feel confident in this link.

Sonex was re-registered on August 10, 1926 by Jean Degoumois of La Chaux-de-Fonds. It initially operated at Rue Aurore 13 before moving to Neuchâtel on February 23, 1934. Degoumois turned the company over to Olivier Dessoulavy on June 17, 1936 and the company continued for many years. The Sonex brand would be part of the larger Degoumois & Co. of Neuchâtel, which also produced the Avia, Protector, Ernest Roth, and Sereka brands. Sonex lasted at least through 1962 as part of “Fabrique de Montres Avia, Degoumois & Co.”

Avia was originated by the Rode Watch Company in the same space at the Montbrillant factory prior to the arrival of Sonex/Darax, which is quite an interesting coincidence! Avia was re-launched by Degoumois in 1945 in association with Louis Newmark of the UK and became a famous brand there. Degoumois/Avia merged with Silvana as part of Société des Garde-Temps SA (SGT) in 1968 and lasted until bankruptcy in 1980. The following year, Avia was re-launched as a mass-market brand by Louis Newmark in the UK, and this would be the end of the lineage of Eugene Meylan’s other watch brand.

Although the same address in Neuchatel was shared with the Swiss incarnation of the famous American company, Elgin, in the 1960s, there is no evidence of a relationship between Degoumois and Elgin until both fell under SGT in the 1970s.

The Early Years of La Glycine

The Death of Eugène Meylan

The facts of the death of Eugène Meylan were reported in the newspaper L’Impartial, as uncovered by Emre Kiris during his research. I am presenting his clippings here for posterity, since they were posted to Watchuseek and may be deleted in the future. Here is my translation of the article:

A Former Chaux-de-Fonnier Assassinated in Neuchâtel

We discover a corpse at the Mail

(Corr.) – A worker who was going to work on Saturday, discovered shortly before 8 a.m., not far from the shooting range at the Centre du Mail in Neuchâtel, the corpse of an unknown lying on his stomach, face down on the ground, in the middle of a pool of blood. He was a very stout man, looking about sixty years old, and his clothes were wrinkled and torn as if the body had been dragged quite a long distance.

The police, immediately notified, had the body transported to the mortuary of the Cadolles Hospital where Dr. Clerc, forensic doctor, carried out an autopsy. This revealed that the stranger had been killed by violent blows to the head and upper part of the body.

The identity of the victim

In addition, the investigators were soon to learn the identity of the victim. He is a former Chaux-de-Fonnier, Mr. Eugene Meylan, born in 1891, who was a watchmaker and who, a few years ago, left first for Lausanne, then for Geneva where he was in charge of the finishing and sale of watches, on rue Dancet 1.

The examining magistrate, Mr. H. Bolle, who was presiding on Saturday over the conference of French-speaking examining magistrates, gave up his honorary functions to engage – with the security police – in a quick investigation. Due to the position of the body and certain clues found, one could think of several hypotheses: fight, accident caused by a reckless driver who would have concealed the body of his victim, or villainous crime.

Arrest of the murderer

However, with commendable speed, investigators were able to reconstruct the facts as they unfolded yesterday. They noted, in fact, that Meylan, who came from Geneva, had met at the Workers’ Circle, in Neuchatel, a young “zazou” named Edouard Glatz, born in 1937, apprentice mechanic, living with his parents.

The two men left the Circle at around 3 a.m. on Sunday morning and headed towards the Mail. It was in this remote location that Glatz knocked out his companion, stripped him of his money, and concealed the body.

The young assassin was arrested Sunday morning and imprisoned. We are faced with a “villainous” crime committed at the end of a particularly stormy scene.

During this argument, Glatz, grabbing a stone, struck his companion violently on the head.

This crime was widely reported at the time, and the later stories are much less sympathetic to Meylan. Indeed, he is widely blamed for the assault, having made “immoral” advances on the young Edouard Glatz, who is often described as attractive and even innocent. Glatz was sentenced to just 5 months imprisonment, with the murder charge dropped, and even this punishment was suspended. In 1958, Glatz was arrested again for robbing a pharmacy, with coverage noting “the drama in which he killed a homosexual” without naming Meylan.

We discover a corpse at the Mail

(Corr.) – A worker who was going to work on Saturday, discovered shortly before 8 a.m., not far from the Mail shooting range, in Neuchâtel, the corpse of an unknown lying on his stomach, face down on the ground, in the middle of a puddle of blood. He was a very stout man, looking about sixty years old, and his clothes were wrinkled and torn as if the body had been dragged quite a long distance.

The police, immediately notified, had the body transported to the mortuary of the Cadolles hospital where Dr. Clerc, forensic doctor, carried out an autopsy. This revealed that the stranger had been killed by violent blows to the head and upper part of the body.

In addition, the investigators were to learn soon after the identity of the victim. This is a former Chaux-de-Fonnier, Mr. Eugene Meylan, born in 1891, who was a watchmaker and who, a few years ago, left for Lausanne first, then for Geneva where he was in charge of dressings and the sale of watches, rue Dancet 1.

The examining magistrate, Mr. H. Bolle, who was presiding on Saturday over the conference ofFrench-speaking examining magistrates, gave up his honorary functions to engage – with the security police – in a quick investigation. Due to the position of the body and certain clues found, one could think of several hypotheses: fight, accident caused by a reckless driver who would have concealed the body of his victim, or villainous crime.

However, with commendable speed, investigators were supposed to reconstruct the facts yesterday as they unfolded. We noticed, in fact, that Meylan, who came from Geneva, had met at the Cercles des Travailleurs, in Neuchatel, a young “zazou” named Edouard Glatz, born in 1937, apprentice mechanic, living with his parents.

The two men left the Circle at around 3 a.m. on Sunday morning and headed towards the Mail. It was in this remote location that Glatz knocked out his companion, stripped him of his money, and concealed the body.

The young assassin was arrested Sunday morning and imprisoned. We are faced with a “villainous” crime committed at the end of a particularly stormy scene.

During this argument, Glatz, grabbing a stone, struck his companion violently on the head.

The criminal of the Mail has been in the hands of justice since Sunday morning. We cannot predict what the results of the investigation will be. but it is obvious that the personality of the young criminal will influence the verdict of the judges. However, Edouard Glanz was not known to be devious. On the contrary, he was unknown to the police services and the member of the circle who had him at his home from Friday to Saturday had never seen him.

Glatz, in recent days, took over from his father, who was on vacation, as an operator in a cinema. from the city. He was paid for this work and had no need for money. He was a good friend, often went mountain races with his friends, and they were appalled when they learned, Monday morning, of the arrest of the young apprentice.

We are not dealing with a mad being, but undoubtedly with a boy who, under the influence of alcohol and being in the company of an elder of abnormal morals, was seized with a fit of anger. Glatz punched Meylan hard, then punched him on the head with a stone. Dang his rage, he again took his victim’s wallet to, one might suppose, crown his revenge.

Glatz did not learn until Saturday afternoon that he had killed Meylan. He hesitated for a long time to go and report himself to the police and finally did not have the courage. We know the rest.

After the Mail drama

A decision of the Indictment Chamber (Corr.) – We remember the drama that broke out on the night of September 23 at the Mail and during which the named LM, was killed after being struck by a young friend of encounter, Edouard Glatz. The Neuchâtel indictment chamber decided to send the young Glatz back to the criminal court and not to the Assize Court. He was in fact warned of robbery and bodily harm. Due to the circumstances in which the tragedy occurred, the prevention of murder was dropped. The aggressor thus escapes the Assize Court.

Glatz condemned

at five months, suspended

The drama of the Mail, which took place east of Neuchâtel, on September 23 and during which a 64-year-old former industrialist, Mr. Eugène Meylan, was killed in a violent fight with a young man of 18 years old. , Edouard Glatz, apprentice-mechanic, to whom he had made immoral proposals, was tried Tuesday by the Correctional Court of Neuchâtel.

The court rules out robbery which requires the intention of theft; however, this intention has not been proven. On the other hand, if self-defense cannot be accepted, there is an “undeserved offense” which angered G. This circumstance, as well as the age of the accused, must mitigate the sentence imposed for grievous bodily harm. and flights. Consequently, the court condemns the defendant to 5 months of imprisonment, less 127 days of preventive, and to the payment of the expenses by 1743 fr. 10. The stay is granted to G. with a probation period of 3 years.

The crime of the Mail. – What really happened? Edouard Glatz, the blond young man who killed Meylan, had resumed his work as an apprentice mechanic on Saturday morning, as if he did not have a crime on his conscience. He said he learned of his victim’s death from a newspaper. According to him, Meylan, a known homosexual, would have liked to take advantage of their privacy to satisfy his erotic desires as an invert. It was while defending himself that he struck him with a violent punch. But this version seems to be well invalidated by the fact that he then hit his victim on the head with a stone, then he shuffled his pockets back to him to steal around thirty francs.

The former director of the Bullclock watch factory in La Chaux-de-Fonds, who died under the blows of the criminal, cannot contradict his assertions. Justice, which has shown a remarkable speed in the search and discovery of the culprit, will have to show the same sagacity to know exactly what happened.

After a deadly brawl

NEUCHATEL, January 31. (Ag.) – The drama of the Mail, which took place east of Neuchâtel, on September 23 and during which a 64-year-old former industrialist, Mr. Eugène Meylan, was killed during a fight with a young man of 18, Edouard Glàtz, apprentice mechanic, to whom he had made immoral proposals, was judged maidi in Neuchâtel. The murder order was dismissed. Glatz was tried for bodily harm resulting in death and for theft because he had robbed his victim. He was sentenced to 5 months suspended imprisonment and the costs of the case.

On the wrong track

(CP.) – The police proceeded to the arrest, these last days, of a young man of Neuchâtel, named Edouard Glatz, accused of having burgled a drugstore in the center of the city. Glatz is none other than this young murderer who has been talked about a lot there. a few years ago following the drama in which he killed a homosexual. It seems that the indulgence he enjoyed at that time was of little use.

Leave a Reply