On June 13, 1987, noted Parisian jewelers Pierre and Jacques Chaumet were taken into custody for bankruptcy, breach of trust, and fraud. The distinguished gentlemen would be convicted of all these crimes, losing control of the House of Chaumet, one of the most celebrated names in jewelry, as well as Breguet, which enjoyed a similar reputation in watchmaking. The story of the rise and fall of Chaumet is even more fascinating for what is not known about the case, however, and what it tells us about the modern aristocracy.

Note: The Chaumet brothers appear to have been experts in keeping their photos out of the papers. Although the case is well-documented in period news coverage, there is not a single photo of the brothers in any newspaper I could locate! Instead, I am using a photo from the excellent French-language 2017 blog post by Richard Jean-Jacques, “L Affaire Chaumet, un scandale étouffé.”

Nitot, Fossin, Morel, and the First Wristwatch

Before Chaumet, it was Nitot.

The House of Nitot designed Napoleon’s coronation sword and the wedding jewels used for his first marriage to Joséphine de Beauharnais and his second to Marie Louise. But the name is best remembered in horology for creating a match set of bracelet watches given to Princess Augusta-Amélie, bride of Joséphine’s son, Eugène. Said to have been created in 1811, this is often celebrated as the world’s first wristwatch!

Marie-Étienne Nitot was born in 1750 and became apprenticed to the Aubert, jeweler to Marie-Antoinette. Nitot established his own jewelry house in 1780, serving aristocrats and the wealthy of Paris before and after the French Revolution. A famous (though perhaps apocryphal) story tells that Napoleon Bonaparte’s carriage came out of control along the rue Saint Honoré and Nitot’s staff was able to assist and shelter the First Consul and future Emperor in his shop. Napoleon is said to have remembered the jeweler in 1804 and given him the task of producing his coronation jewels. This fantastical and unlikely story was no doubt re-told by Joseph Chaumet, inheritor of the Nitot legacy, and appears as far back as a 1933 issue of La Fédération Horlogère.

Marie-Étienne Nitot died in 1809, shortly before Napoleon annulled his marriage to Joséphine in search of an heir. François Regnault Nitot took over his father’s business and proved a capable jeweler and businessman. It is said that Regnault traveled across Europe with Joséphine and Marie Louise, influencing the tastes of the aristocracy and building a remarkable clientele in just a few years.

Notably, Nitot created a pair of bracelets around 1811 as a gift from Joséphine to her daughter in law, Princess Augusta of Bavaria. One featured a calendar while the other included a watch movement. These are widely said to be the forerunner of the wristwatch, and their appearance in the early 19th century was mentioned as an inspiration for the proliferation of bracelet-mounted watches among the ladies of court in the decades that followed. For a sense of the history of this tale, see the 1933 article from La Fédération Horlogère in the References section below.

Napoleon’s defeat and exile spelled the end of François Regnault Nitot’s career, however. He turned over the firm to his shop foreman, Jean Baptiste Fossin. Along with his son, Jules, Fossin adapted to the changing tastes of the French elite and remained a key producer of jewelry for Kings, Princes, and the emerging creative class.

But the establishment of the Second Republic in 1848 deeply impacted the jewelry business in France. Fossin contacted his former chef d’atelier, Jean-Valentin Morel, who had moved his business to London in 1850, seeking a new market for his work. Along with his son, Prosper, Morel gained the favor of Queen Victoria, as well as a royal warrant, but business there was slow. Jean-Valentin died in 1860 and Jules Fossin in 1869, leaving the struggling Anglo-French business to Prosper Morel.

The House of Chaumet

Joseph Chaumet married Marie Morel in 1885, gaining control of the firm inherited by his wife. He re-dedicatd the firm with his own name and re-focused it in service to the Parisian elite. In 100 years of family control, the House of Chaumet reached the highest levels of society and success, becoming synonymous with wealth, taste, and class.

Chaumet specialized in tiaras worn by the aristocracy and incorporated new elements of Asian and Art Deco style. These were sold from a boutique at the Hôtel Ritz Paris at number 15 Place Vendôme, but in 1907 the firm would establish a presence across the square at 12 Place Vendôme. This remains the home of Chaumet today, and the address is perhaps as important to the firm as Joseph’s famous name.

Marcel Chaumet took over from his father in 1928 but the firm suffered greatly in the Depression. It was shut down in 1934 as the economy and mood in France turned sour.

After World War II, Marcel Chaumet re-established his business at Place Vendôme alongside “New Look” pioneers Christian Dior and Yves Saint Laurent. Soon the firm was the talk of the town among fashionable ladies in Paris, and it began to attract notice in America as well.

Marcel’s sons, Jacques and Pierre Chaumet, took over as executive directors in 1958 and they proved a dynamic and successful pair. Jacques directed the business and re-established the Chaumet name in social, government, and foreign circles while Pierre gained a name as one who could procure and present any jewel desired by a client.

Image: New York Times, July 12, 1971

Throughout the 20th century, Chaumet acted as a de facto diplomatic arm of the French nation. Joseph had courted Abd al-Aziz of Morocco on behalf of the French government and his grandson Jacques became close to Hassan II 70 years later. Chaumet is said to have sheltered with the king in a pool house during a deadly 1971 coup attempt, and the pair were fast friends since then. Chaumet also played a role in diplomacy with Mobutu of Zaire, who built an extra-long runway so he could charter the Concorde for shopping trips in Paris. Although Mobutu eschewed European suits he loved Chaumet’s jewelry!

Image: Europa Star Trade Bulletin 926, 1980

Image: Europa Star 145, 1984

Jacques and Pierre Chaumet were also instrumental in bringing the legendary Breguet watch brand back to Paris. Abraham-Louis Breguet‘s great grandson had turned his family’s watchmaking firm over to the Englishman Edward Brown in 1870, and it remained in the Brown family until the Chaumet brothers purchased it 100 years later. Throughout the 1970s Chaumet worked with a variety of Swiss watchmakers and manufacturers to re-establish the Breguet name in watchmaking. They faced many challenges, from the currency and oil crises of the 1970s to the rise of quartz, but the brand continued on and off through the 1970s.

Chaumet established a new Montres Breguet SA in Le Brassus in 1980. This iteration of Breguet was officially re-launched at the MIH in 1983 after a few initial products starting in 1981. Notable contributors to Breguet watches in the early 1980s included Daniel Roth and Michel Parmigiani, who produced complicated movements for the resurgent brand. The company would ultimately be successful, acquired by Investcorp after the Chaumet’s legal troubles in 1987 and later by Swatch Group in 1999.

The Diamond Bubble

The 1970s was a decade of economic booms and busts. After the Nixon shock and the end of Bretton Woods, the price of commodities like gold and oil began to fluctuate dramatically along with the relative value of various currencies. In nominal US dollars, gold swung from a low of $496 in 1974 to a high of over $3,000 per ounce in 1982! The price of oil, which had been relatively steady for 100 years, suddenly tripled in 1973 and doubled again in 1979.

It was in this environment that the world’s wealthy turned to diamonds as an alternative investment. The De Beers cartel’s control of both mining and advertising gave these sparkly stones an aura of permanence and stability that most other commodities lacked. Flush with cash and looking to invest, buyers turned to loose 1 karat diamonds as an alternative to gold ingots or real estate. The diamond industry embraced this newfound market, with the influential Rappaport Diamond Report launched in 1978 to cater to investors.

By 1981, jewelers like Chaumet and Cartier had transformed their business from ornamentation to investment. Place Vendôme had become as influential a world financial capital as New York, London, Frankfurt, and Tokyo! For a short time, loose 1 karat diamonds were actually more valuable than 1.25 karat stones or those set in gold jewelry.

The Chaumet brothers had long enjoyed their international status and nurtured this new clientele. They grew close to royalty from the Middle East and Africa, and welcomed them as investors. Chaumet’s Geneva office became an essential option, accepting cash and Swiss account transfers for shares of diamonds held in the company’s Paris vaults. Wealthy French customers became involved as well, with some allegedly using Chaumet’s Geneva diamond connection as a way to avoid taxes.

Around 1980, Chaumet began overtly selling financialized diamonds as an investment, promising between 15% and 25% annual returns. The company removed jewelry and even the stones themselves from the equation, acting (as they would later be charged) as an unlicensed bank or investment company. This strategy looked brilliant as the price of a one-carat flawless diamond jumped from around $1,600 to over $62,000 that year in one of the most spectacular commodity bubbles in history.

Unsurprisingly, the diamond market collapsed in the 1980s. That $62,000 diamond dropped to $45,000 in 1981, $26,000 in 1982, and just $13,000 in 1983. While other jewelry firms were diversified with investment in other types of gems and precious metals, nearly all of Chaumet’s money was tied up in diamonds. And diamonds were suddenly worth much less than the company or their customers imagined.

According to the charges brought against the brothers in 1987, Chaumet scrambled to meet the expectations of their customers. They took on debt, which was easy to access for the historic and respectable firm, with banks extending over a billion French francs to the company despite the fact that their annual turnover was only 125 million francs by 1986. They began borrowing from their friends and customers as well, reportedly wiping out Mobutu’s 60 million franc debt and borrowing far more from him. And these were structured as interest-paying investments, digging the brothers even deeper in debt.

With the company’s finances already in tatters, the Chaumet brothers made one last massive bet: They purchased a new showroom in New York between Park and Lexington Ave. 48 East 57th St. was a showcase for the best the company could offer, with Pierre and Jacques Chaumet apparently hoping to sell their way out of debt. But it was financed on unfavorable terms and spelled the end of their available cash.

Once Chaumet ran out of assets to use as collateral for loans they began offering jewelry belonging to customers stored in their vaults. During the trial, The Washington Post describes a pearl necklace belonging to a French princess that was broken up and sold by the firm. Many such stories surfaced in later years, with Jacques Chaumet’s customary discretion and informal handling of assets used to hide desperate shuffling of jewelry to raise funds. And of course the company kept taking in more money and jewels from customers, a classic Ponzi scheme tactic.

In December 1984, Pierre Chaumet was taken into custody by the French customs agency (DNED) when he was caught transferring large amounts of cash between Paris and Geneva. The case involved hundreds of millions of French francs and likely related to the fraud described above as well as evasion of taxes for the company and its customers. But the case was mysteriously dropped (due to politics, according to a 1987 article) and the Chaumet scheme was allowed to continue.

The Fall of House Chaumet

By 1986 the Chaumet brothers realized that the game was up. Wholesale gem and precious metal dealers no longer allowed Chaumet to purchase on credit after the firm repeatedly missed payments. With their supply of raw materials drying up and their vaults and bank accounts rapidly emptying, the brothers sought a buyer for the historic family firm. They attempted to arrange a deal with their New York subsidiary and private equity firm Investcorp, which then owned Tiffany, and also proposed mergers with Vendôme rival Boucheron. News of these moves leaked to the press in May, 1987, with the brothers suggesting that the sale was on their initiative.

On June 11, after a hearing of the commercial court, Jacques and Pierre Chaumet were taken into custody on criminal charges of “bankruptcy, breach of trust, and fraud.” The historic showroom at Place Vendôme was closed by French Police and the company’s account books taken for investigation. What they found would take years to unravel, and the complete story was likely never told.

Although the company owed over $1.8 billion French francs to creditors, it is widely reported that there was far more debt than this off-books. Jacques preferred to work based on handshake agreements and utmost discretion with clients. The Post’s princess, for example, apparently did want to sell her necklace but protected her reputation by sending a letter to Chaumet stating exactly the opposite. It is likely that most of their agreements were similar, with no paper trail or definitive chart of accounts. Given the company’s presence in Geneva, we can assume that many clients simply walked away from their investments, preferring to protect their name from police inquiry.

Despite the scope of the fraud committed, very few clients were pulled into the case. One notable exception was Albin Chalandon, then Minister of Justice and head of the office that prosecuted the case. Chalandon reportedly tried to hide the fact that he and his wife, Princess Salomé (Murat), had invested $6 million francs with Chaumet and was receiving interest payments from the firm. Once it came out in court, his dismissive answers became a minor scandal for the government of French President François Mitterrand. It has been suggested that the involvement of politicians like Chalandon and international figures like Mobutu is one reason for the lack of further investigation into Chaumet’s investment clients. Indeed, Princess Salomé’s niece was by then the wife of Jacques Chaumet’s son!

The brothers were finally convicted and sentenced in 1991. Taking into account six months of detention prior to their trial, Jacques Chaumet received a term of 18 months in prison and Pierre Chaumet was sentenced for a year. They were also ordered to pay a fine of 500,000 French francs each. On sentencing, the judge summed up the case: “They have committed almost all the offenses that it is possible to commit in a company. They betrayed the trust of their employees and brought to ruin a jewelry store known not only throughout the world but also in history.“

And yet, apart from the short sentences for the Chaumet brothers, everyone else walked away.

Chaumet and Breguet Today

Despite the promises made by Jacques Chaumet, the firm was not able to arrange a merger with one of its Place Vendôme neighbors. The accounts were too convoluted and toxic for any other jeweler to touch, and one imagines they might have had their own legal or financial exposure after the diamond bubble burst.

Chaumet was instead purchased by Investcorp, an Arab/American private equity company. For the sum of 410 million French francs, Investcorp received the assets of Chaumet of Paris and Montres Breguet of Le Brassus free from any entanglement with the Chaumet brothers’ crime. Investcorp was widely respected for having “rescued” Tiffany from Avon Products in 1984, followed by a successful IPO in 1987 that likely provided some of the funding for the acquisition of Chaumet. And Investcorp then and now has a better reputation than many in the private equity world, preferring to invest in companies rather than sell them for parts.

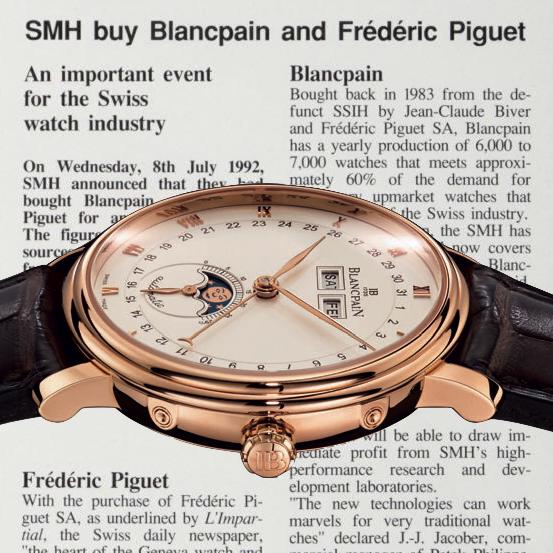

Investcorp proved a better manager of Chaumet and Breguet than the brothers. The group purchased complicated movement specialist Nouvelle Lemania in 1992, combining this under Groupe Horloger Breguet. They invested in Breguet through the 1990s, building a new manufacture in L’Abbaye in 1996 and growing the company into a credible competitor for Blancpain, which had been purchased by Nicolas Hayek’s SMH in 1992. It is often said that Hayek would have preferred owning the Breguet name but could not reach an agreement with Investcorp and went for Jean-Claude Biver’s Blancpain instead.

1999 saw an incredible process of consolidation in the luxury goods industry. A complex deal saw Richemont purchase LMH (IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre) on July 21, beating LVMH and PPR. The two had previously been buying shares of Gucci (which Investcorp purchased between 1988 and 1993 and sold to the public a few years later) and PPR reached a deal to acquire the Italian firm on September 10. Three days later LVMH purchased TAG Heuer and the very next day Swatch Group acquired Groupe Horloger Breguet from Investcorp. LVMH took Chaumet from Investcorp on October 20 along with Ebel. On November 15, Zenith went to LVMH as well.

Split up, Chaumet has returned to its roots (and renovated its famous showroom) to become the “crown jewel” of LVMH. Breguet similarly sits atop the Swatch Group pyramid, joining Blancpain and Jaquet Droz in a special “prestige and luxury” division under Marc Hayek.

Image: SJMeinhofer

The Grail Watch Perspective

The success of Chaumet and Breguet since the 1990s has wiped the Chaumet affair from the public consciousness, and their new corporate owners would never allow that type of fraud to reoccur. But the case illustrates the strange world of wealth in the 1980s, when the world’s rich and powerful mixed over gold and diamonds on Place Vendôme. The jewelry and watch business was much different then, though the tactics of the ultra-wealthy will never change.

It would be easy to vilify the Chaumet brothers, and they have been judged guilty of the crimes listed here. But they also lead their family firm to new heights, living up to the legacy of their grandfather, Joseph Chaumet, and the pioneering François Regnault Nitot. The fall of House Chaumet was all the more tragic given their success in the 1960s and their efforts to reclaim the French heritage of Montres Breguet in the 1970s. And we should not forget that there were many other guilty parties in this tower of greed, most of whom were never named. Jacques and Pierre Chaumet took the fall for it all.

References

Perhaps the best accessible account of the Chaumet Affair is this French-language blog post by Richard Jean-Jacques from 2017: “L Affaire Chaumet, un scandale étouffé” tells the tale of the Chaumet brothers and their fall, drawing heavily on Alain Barbanel’s 1988 book, “l’Affaire Chaumet” as well as news stories.

Although the story was widely covered in international news at the time, these stories notably lack photos of the Chaumet brothers and any sense of closure. A careful reading can reveal part of the story, however.

- “Les ancêtres de la montre bracelet” – La Fédération Horlogère, September 13, 1933

- “Have You Ever Tried to Sell a Diamond?” – The Atlantic, February 1982

- “Chaumet joailliers Paris nouvelle tête” – FAN L’Express, May 23, 1987

- “Enquête douanière classée” – L’Impartial, June 22, 1987

- “A Scandal in French Jewelry” – New York Times, June 15, 1987

- “Montres Breguet S.A. au Brassus l’avenir dans les mains d’Investcorp” – L’Impartial, July 16, 1987

- “Nouveau PDG pour Chaumet” – FAN L’Express, November 5, 1987

- “Enchères fabuleuses” – L’Express, November 15, 1988

- “Les joaillers jugés” – L’Impartial, October 1, 1991

- “The Unpolished Tale of the Princess and the Pearls” – The Washington Post, October 16, 1991

- “Ex-Owners of Renowned Paris Jewelry Firm Sentenced to Prison” – AP, December 17, 1991

- “Diamonds Aren’t an Investor’s Best Friend” – The Wall Street Journal, February 12, 2012

Leave a Reply