Longines isn’t just the name of the biggest watchmaker in Saint-Imier today, it represents a factory and a critical shift in the industry to industrial-scale mass production. Ernest Francillon and Jacques David were critical to the development of the horology industry in the 19th century, abandoning the etablissage system and industrializing watchmaking, and becoming champions for the integration of manufacturing in the 20th century. Today Longines remains one of the largest Swiss watchmakers and is a key component of the dominant Swatch Group. And it owes its start to a forward-thinking young watchmaker named Ernest Francillon in the 1860s, his colleague Jacques David in the 1870s, and an alarm raised at the Philadelphia Exhibition of 1876.

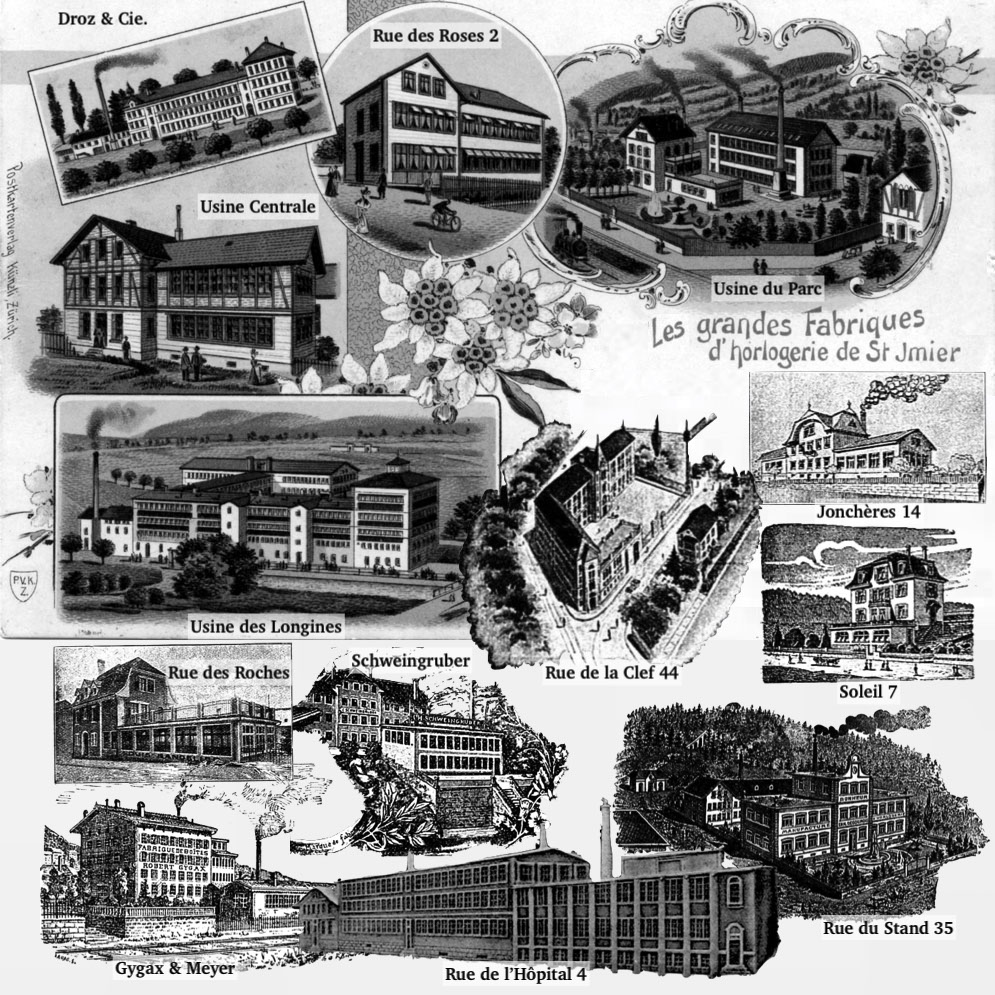

Les Grandes Fabriques d’Horlogerie de Saint-Imier

This is part of a series of posts about Les Grandes Fabriques d’Horlogerie de St Imier. Due to the detailed and complicated research required, it will likely take months to complete, so please subscribe to the Grail Watch newsletter to be kept up to date!

- Introducing the great watchmaking factories of Saint-Imier

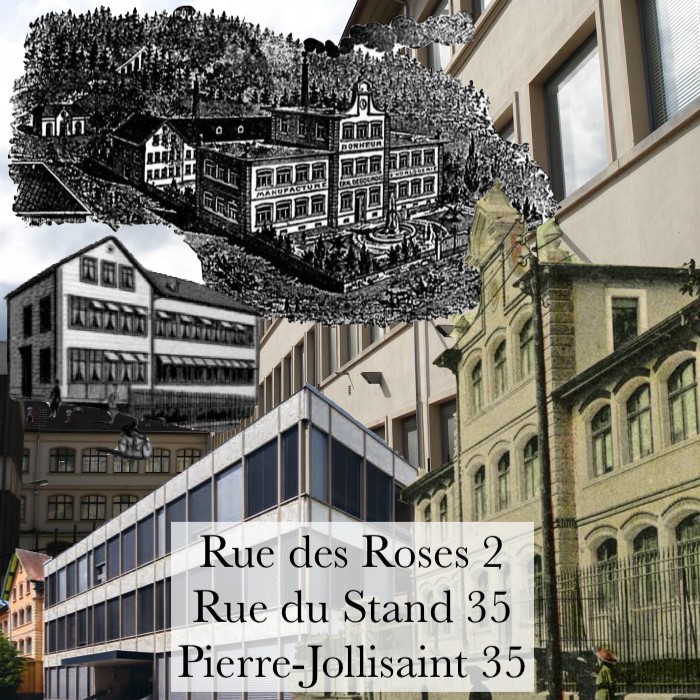

- The Evolution of Watchmaking Architecture: Rue des Roses 2 and Rue du Stand 35

- Excelsior Park: Usine du Parc

- The Rise of Mass-Produced Watches at Les Longines, Saint-Imier

- From Atelier to Factory: Usine Centrale, Saint-Imier

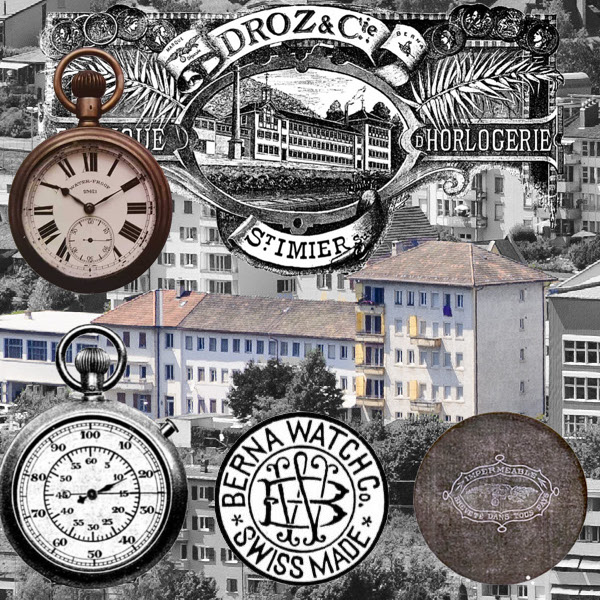

- Droz and Degoumois: Berna Watch Factory

- Rue de la Clef 44: Fritz Moeri’s Moeris

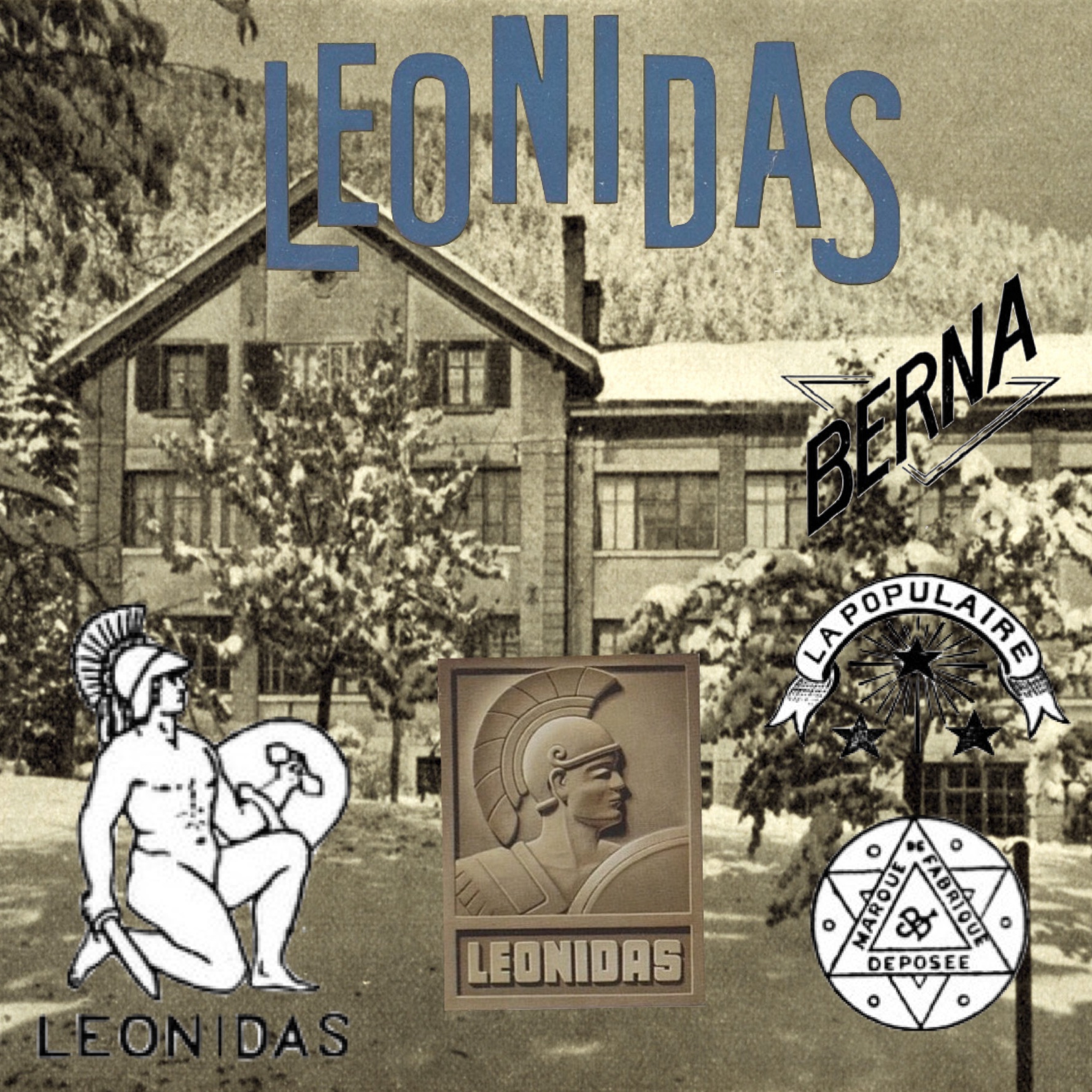

- The Rise and Fall of Leonidas and the Beau-Site Factory

- Gygax & Meyer

- Schweingruber

- Smaller Factories of Saint-Imier

Each of these factories has a story to tell, both about the products produced there and the watchmaking industry at the turn of the 20th century. We will explore the transition from home to factory, the rapid rise of corporations, the transition from water and steam to electric power, the great Jeanneret family, and more!

The Roots of Watchmaking in Saint-Imier

Saint-Imier was a little slower to adopt watchmaking than nearby towns like Le Locle and La Chaux-de-Fonds, and was considered quite remote through the 18th century. There were a few watchmakers in town at that time, notably the Meyrat and Nicolet families, but it was not until the 1850s that the valley would truly develop. With the the Napoleonic wars, Swiss Restoration, and Sonderbund War behind them, the liberal governments began to connect the remote valleys of Switzerland with improved roads.

In 1832, 23 year old Auguste Agassiz (brother of famous geologist Louis Agassiz) moved to Saint-Imier to study watchmaking under Henri Raiguel. Agassiz soon took over the business, which was located near the center of town, working closely with Edouard Savoye next door. The two families were extremely close, and the Agassiz and Savoye names feature prominently in the history of Longines and of the town itself.

Over the next 20 years the business of Agassiz and Savoye became prosperous, with sales focused on outlets in Frankfurt and Leipzig for the German market as well as in America. It was an etablisseur, with the small staff producing finished watches in watch cases using movements produced in Fontainemelon but finished by independent watchmakers. Although initially a partnership, Agassiz was solely in charge of the firm by 1849.

Agassiz’ sister married Lausanne businessman Marc Francillon, and their first child was born in 1834. An excellent student, Ernest Francillon studied in Stuttgart before taking on an apprenticeship with a watchmaker in Val-de-Travers. Seeing his potential, his uncle Auguste Agassiz brought him into the firm in 1854, and Francillon quickly rose to manage the operation. Agassiz suffered a chronic illness by this time and was forced to give up day-to-day operation of the company and move to Lausanne. By 1865 Ernest Francillon’s name was used by the firm rather than that of his uncle. Auguste Agassiz died on February 25, 1877, but he was not forgotten: A former mayor of Saint-Imier, his name was now applied to the street where his workshop, and those of other watchmakers, was located!

Image: Longines

By the 1860s, Ernest Francillon was one of the leading watchmakers in Saint-Imier, and could easily have spent the rest of his life assembling watches as his uncle had before him. But Francillon soon saw a new future for the industry rooted in mechanized mass production. This would be his legacy, and his Longines Watch Factory would become one of the most famous brands in the world.

The Battle Over Mass Production

Swiss watchmaker Pierre-Frédéric Ingold was perhaps the first proponent of automated mechanical watchmaking. But his inventions were met with hostility in his home town of La Chaux-de-Fonds, with workers fearing that mechanization would destroy the system of labor that had spread across the Jura region after Daniel JeanRichard popularized it in Le Locle a century before. Ingold had created the first keyless winding mechanism and introduced jeweled movements to Switzerland but was forced out of the country.

Ingold worked for Breguet in Paris but his attempt to set up a watchmaking factory with Berthoud and Japy in France was met with similar resistance. He moved to England, inventing and patenting watchmaking machines for the British Watch Company in the 1840s, but workers destroyed his Soho factory. He then traveled to America, setting up the first watchmaking factory there in 1852, but was forced out by his American partners. Pierre-Frédéric Ingold died in 1878, never seeing his ideas come to fruition, though his heirs did find success thanks to his invention of a gear wheel cutting machine. Ingold was especially despised by the socialist workers gaining prominence at the time, and was attacked even after his death in their newspaper, La Sentinelle. At some point I will write more about this intriguing innovator!

Mass production was already in use in some areas of watchmaking, including in Switzerland and France. Frédéric Japy, a student of Le Locle watchmaker Abraham-Louis Perrelet, built a factory to mass produce clock movements in Beaucourt France around 1770. He was soon selling thousands of movements plates and dials per year to clockmakers across the Swiss Jura region. Japy’s success inspired the 1793 construction of a similar factory in Fontainemelon near La Chaux-de-Fonds, and this company soon also took over a large water-powered factory in Corgémont. These three factories had a near monopoly on the construction of movement plates throughout the 19th century, and Robert & Cie. (Fontainemelon) would become a key element of Ebauches SA and today’s ETA!

See my article “How Tiny Fontainemelon Dominated Swiss Watchmaking in the 19th Century” for more!

But we must draw a distinction between machining, mass production, centralization, vertical integration, mechanization, and interchangeability.

Japy and Fontainemelon employed thousands of workers in their factories, but their machinery was operated by hand and their incomplete ébauches needed a great deal of reworking before they could be used. Ingold was a proponent of mechanized production, which would have reduced the need for workers and standardized the components. The same approach was true of the great Waltham Watch Company in the United States, which would inspire the creation of the Longines factory as we know it.

Georges Favre-Jacot (Zenith) and Ernest Francillon (Longines) would favor a “vertical” approach in the 1880s, with all aspects of production under one roof. This implied centralization and mass production but might not have resulted in mechanization or true interchangeability.

Establishment of the Longines Watch Factory

In the 1860s, Ernest Francillon saw an opportunity in breaking Fontainemelon’s virtual monopoly on machined movement plates. In 1866, Francillon began refitting a mill building on the opposite side of the Suze river in the valley below Saint-Imier.

Water power was rare in Switzerland at this time, since most rivers flooded regularly, leaving marshes and meadows that made it difficult to built. But there were a few rocky spots that were amenable to water power. One was the Corgémont site of the Robert (Fontainemelon) factory. Another was a rocky spot along a creek in the valley below Saint-Imier. The meadows there were known as “Les Longines,” giving the factory and eventual watch brand its name.

Because the means and tools of mechanical production were a closely-guarded secret, the Longines team had to develop everything from scratch: Gauges, tools, machines, lathes, saws, drills, jigs, and even the power systems. The Longines factory soon produced its first 18 and 20 ligne watch movements, but these had a primitive lateral escapement and were key-wound.

Image: Longines

Ernest Francillon’s young cousin, Jacques David, joined the company in 1867, though he quickly quit due to the disagreeable nature of the elderly watchmaker in charge. But Francillon persuaded him to return in 1869 as technical director, and David proved his worth designing watchmaking machinery.

Soon, the company’s first pendant-wound anchor escapement watch was produced, and this would become the signature of the factory. Francillon submitted one of these watches to the American Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876, with Swiss judge Edouard Favre-Perret noting it was of “complete manufacture by machines.” Thus the legend of Longines was established around the world based on the gold medal received by this watch in Philadelphia.

Théodore Gribi and Jacques David’s Warnings

Image: Richard Watkins

Ingold’s ideas lingered in America, and his concept of mechanized mass production was taken up by Aaron Dennison and the Waltham Watch Company. In the 1860s, mass-produced American watches began appearing in the Swiss market, and by the 1870s the volume of American imports to Europe caused a crisis. The Swiss tradition of hand-made watches could not compete with industrial production.

The Longines 20A pocket watch wasn’t the only thing Francillon sent to the Philadelphia Exhibition. When word came back to Switzerland from Théodore Gribi, representative of the Intercantonal Society of Jura Industries, that the Swiss had been “overtaken by our competitors in the New World,” Francillon arranged for Jacques David to travel to America. He arrived by August 1876, attended the Philadelphia Exhibition, and traveled with Gribi to visit various American watchmaking factories.

When Jacques David returned to Switzerland in November 1877 he wrote a long and detailed report to the Intercantonal Society warning that the American manufacturing methods would render the Swiss watchmaking industry obsolete. This echoed the public comments of Edouard Favre-Perret and Théodore Gribi, who were older and much more respected in the Jura. A second report from Jacques David followed in March, this more specific and dire.

David was so concerned that he warned the Society not to widely publicize these warnings. Eight copies of his report were distributed to major watchmakers (including Longines) but no further publicity was made. Today, the best reference to this report is the annotated PDF produced by Richard Watkins based on a copy provided by Longines in 1992. Additionally, Watkins’ 2004 assessment and biography of Jacques David is invaluable.

It is clear that Jacques David was able to implement many of the recommendations made in his 1877 reports at Longines. His recommendations included using machines to make as many components as possible, avoiding hand work, and prioritizing interchangeable parts to reduce labor. Thus, Longines grew from an experiment in the valley below Saint-Imier to its most important producer of watches for a century.

Longines Factory Expansion: 1867-1900

Longines experienced a great deal of success even before Jacques David’s ideas were adopted. The rapid growth of the factory over its first hundred years speaks loudly about the impact of industrial production of watches in Switzerland.

The factory was quickly expanded to accommodate the machinery developed by the company. A floor was added to the mill building in 1868, along with two distinctive dormer towers along the Suze. Longines was now able to produce their own movement blanks and finish and assemble watches in-house, though the company still relied on suppliers for cases (a Saint-Imier specialty), dials, hands, and springs.

In 1878, Longines began producing a chronograph movement, Cal. 20H. It was based on the design of Alfred Lugrin, who also licensed his patents to the Jeanneret family and would go on to found the Lémania company in the Vallée de Joux, a key competitor for Excelsior Park, Leonidas, and Longines of Saint-Imier. These chronographs were advertised in America in 1881 using the Longines name and hourglass logo, the earliest known use of “the world’s oldest trademark.” These won prizes in Paris and Melbourne in 1878 and 1880. Note that although the Longines brand and winged hourglass were among the first trademarks ever issued by the Swiss authority and are among the longest-running in the world, the trademark for Agassiz Fils was actually issued first, since they were processed alphabetically!

In 1881 or 1882 a large new pavilion was added with offices and finishing workshops, and this was the face of Longines through the end of the 19th century. This building was quite similar to the Droz & Cie. factory located along the railroad tracks, overlooking the valley beyond Usine du Parc. Longines quickly abandoned water power, adding a steam boiler and prominent chimney to the old mill, as seen in the 1894 engraving at right. Yet the factory location, down in the valley, was praised by workers for the light, tranquility, and clean air.

1881 also saw Longines introduce a compact 14 ligne movement for ladies watches. This was quite a technical challenge at the time, and demonstrated their manufacturing and watchmaking capabilities. It was followed in 1892 by a 11.5 ligne movement and in 1896 by a 9 ligne ladies calibre, both with highly-refined anchor escapements.

1885 saw a less-successful effort to introduce a cheap mass-produced watch. Although this product category would prove a great success for Moeris and Leonidas, it came at the wrong time for Longines. The company soon abandoned the product and re-focused on higher-quality watches: In 1888, Longines began production of Cal. 21.59, their first certified chronometer movement. Longines would soon win prizes at Antwerp in 1885, the grand prize in Paris in 1889, and a diploma and medal in Chicago in 1893.

In 1882, when the Swiss Federal Institute of Intellectual Property began patent accepting registrations, the Longines brand and hourglass logo were officially registered. They gained worldwide protection in 1893 after being filed with the United International Bureaux for the Protection of Intellectual Property, and Longines remains the longest-registered current brand with WIPO. As the company’s fame grew, so did its recognition. Longines would go on to win 7 grand prizes around the turn of the century: Brussels in 1897, Paris in 1900, Milan in 1906, and Berne and Genoa in 1914.

The next expansion of the factory came in 1900, with a factory wing added at the rear of the property. This is how the Longines factory is pictured on our postcard (seen above left) and was already the largest factory in Saint-Imier. But it was nothing compared to Longines’ early 20th century expansion. By this time, Longines was heavily invested in mechanized production, though they still required a large workforce to operate this machinery. The company was also beginning to deliver truly interchangeable parts, as envisioned by Jacques David.

Ernest Francillon’s life was cut short at 66 on May 3, 1900. He died of influenza just a year after his only son was killed in a military training exercise in Tavannes. He was active until the end, serving as honorary president of the Tir Cantonal Bernois, the very festival which inspired this series of articles!

Just before Francillon’s death, the company formally adopted the Longines brand as its name. On April 20, 1900, it was officially renamed Fabrique des Longines, Francillon & Co.

Longines Crosses the Suze: 1900-1949

The original mill occupied by Ernest Francillon in 1866 was located on the south bank of the Suze along a creek, and the factory remained on that bank through 1900. As seen in the images above, a bridge crossed the river on the west side of the factory, leading to a tree-lined walkway uphill to the railway station and the rest of Saint-Imier. Throughout the 20th century, however, the factory was expanded on the north bank of the river as well, with a canal and culvert constructed to make room for the growing company.

The first expansion on the other side of the river is a separate two-story building near the end of the walkway to town. This building is visible in postcards mailed in 1901 and 1903 (above) and remains in photos and on maps until the 1990s. It is no longer included on the 1994 map and is no longer standing today.

The most visible enhancement to the factory appeared by 1905. The Plan d’Alignement de Saint-Imier that year is the first document showing this new “Fabrique”, a five-story “mansion” with a central pointed turret. Built on the Saint-Imier side of the Suze, it became the symbol for the landmark factory through World War II. The turret was removed after the war and the building was extended, but this remains the main entrance to the factory.

Longines suffered a crippling strike in 1910, and this deeply affected the village and the company. Such actions were common in Saint-Imier at that time, and although the action against Longines was ultimately unsuccessful a similar strike on Montres Berna the following year would nearly drive it out of business.

Jacques David died in 1912, but his place was taken by another remarkable engineer. Alfred Pfister joined the factory in 1896 and his skills soon caught the eye of David, who personally selected him to run the company after his death. Pfister became Technical Director in 1915 and added the responsibilities of Managing Director for the company in 1927. He would lead the company through World War II, and came from a remarkable family of watchmakers: His brothers headed up Terrasse in Le Locle and the large Sonceboz factory!

It is interesting to contrast this new building to some of the other contemporary watchmaking buildings in Saint-Imier in the 1900s. The design is very similar to the new factory constructed by Fritz Moeri across the street from Usine du Parc. And the symmetrical layout of the building is reminiscent of the “mansion” at the Rue du Stand complex after its reconstruction a decade later. But the turret itself has the look of a church steeple, and was perhaps the inspiration for a similar spire on the Christian Catholic Church built on Rue des Roses in 1912.

Photo: Fred Boissonnas

Postmarked 1915

It was noted in the press at the time that Longines was so in need of space that it had leased workshops in the village of Saint-Imier, and this 1914 expansion was intended specifically to enable the company to process and finish watch cases. By 1915, the Longines factory extended over 200 meters from one end to the other and housed 1,500 workers.

The original company was liquidated starting in 1915, with a new Société Anonyme established on May 10. Although it retained the name, Francillon, it was no longer solely run by the family.

The creek feeding the original Longines mill was dammed by this time as well, creating a mill pond above the factory. This was likely intended for flood control now that the Suze river ran between the Longines factory buildings. The pond remained in place until the 1930s but was later drained and has now been replaced by an athletic field and running track.

The creek itself was diverted from the pond through a pipe running under the factory. Around the same time, a canal was built just past the original mill to carry water between the factory buildings, with the main flow of the river diverted to the north. Work to control and redirect the Suze continued for decades, with the main flow redirected around the north side of the factory in the 1950s and filling in the covered canal between the buildings. Today, a wide bridge covers the river, giving access to the parking lots in front of and between the buildings, and the narrow and tree-lined river is almost invisible.

The Modern Longines Factory

David and Francillon’s ideas were proven right in the second half of the 20th century. Rather than assembling components from hundreds of small producers, the company attempted to standardize and bring production under one roof. The factory now spanned the Suze river, welcoming thousands of employees each day.

Longines remained strong through the many crises that befell the industry: Labor actions in the 1910s, over-production and price wars in 1920, the Great Depression of the 1930s, and World War II. The company was able to rapidly adjust production as tastes changed, introducing wristwatches, chronographs, and automatic movements.

Technical and Managing Director Alfred Pfister fell into poor health in 1951, and this caused a crisis for the company since they had not yet picked a successor for him. On September 3 the company hired Fritz Galley, formerly of Ebauches SA’s Fontainemelon and Tissot. He became the company’s technical representative just a few weeks later, as Pfister died on September 17. Galley became Technical Director in 1953, overseeing another expansion of the factory and implementing modern manufacturing methods.

Longines continued to innovate through the 1950s. The company entered the sports timing market in competition with Omega, displacing them as official timekeeper for the Olympics in 1952. This work brought expertise in electric and electric timing to the company, and they were the first Swiss company to build an electro-mechanical chronometer, and launched the first portable quartz clock. Much of this work was taken under Galley’s leadership.

Industry consolidation was a critical need as the Swiss franc appreciated in value in the 1970s. No longer could the old dispersed system of manufacturing last. The Longines factory in Saint-Imier was a model for how Swiss watch manufacturing could compete with cheaper international manufacturers.

Longines formed a holding company by 1970, purchasing Rotary, and joined ASUAG in 1972. It was a formidable competitor for SSIH (Omega and Tissot) and was increasingly integrated with he rest of the industry. On May 26, 1983, it was announced that ASUAG and SSIH would be merged, creating the massive watchmaking conglomerate known today as Swatch Group.

The Grail Watch Perspective

The Longines factory in Saint-Imier is perhaps the most important in all of Switzerland. From Jacques David and Ernest Francillon’s desire to integrate and mechanize production to Pfister and Galley’s work to modernize watchmaking, it provided the model for the modernization of the Swiss industry. Without the success of Longines, it would have been difficult for Nicolas Hayek to imagine a competitive watchmaking enterprise.

But perhaps the Longines model is incorrect as well. Sales of lower-priced Swiss watches continue to drop, and customers are increasingly looking for luxury and hand craftsmanship. Is there a future in the sub-CHF 4000 range occupied by companies like Longines? Indeed, perhaps the bulk of the Swatch Group’s sales are threatened by this new focus. Still, for over 150 years, the factory in “Les Longines” has been an icon of the industry.

References

- Richard Watkins Jacques David and a Summary of “American and Swiss Watchmaking in 1876” is undoubtedly the best reference for David’s “warning” from Philadelphia.

- David Boettcher – Longines: Ernest Francillon & Co.

- Longines Company History – 19th Century

Advertisements

We write in the Journal du Jura:

“The Longines strike last year was a real calamity for our village. The workers’ party, no more than the bosses, did not derive the slightest advantage from it. Quite the contrary, our local industry and trade have been seriously affected. I am convinced that even today, families of workers are suffering the consequences of this unfortunate strike.

“And here we have a new one in prospect. At the Berna factory, this time. All the unionized couriers, numbering about a hundred, gave their fortnight. It would be, if my information is correct, a question of wages misinterpreted by the Syndicate of workmen of ebauches. “.

According to a communication from the central committee of the Workers’ Federation, the conflict would have for origin the refusal by the Management of the factory to accept the demands of the workers on drafts concerning a larif.

La Fédération Horlogère Sep 23, 1911

This important horiogery factory will increase with a new construction. Work will begin as soon as weather permits. At the moment, workers are clearing the place. In particular, they remove trees. We will see the disappearance with regret of two enormous poplars, several centuries old and whose trunks measure a meter and a half in diameter at the base. These two giants face each other, at the bottom of the path that goes up from the Longines to the cemetery.

The new building will continue towards the East the body of the various existing constructions. 45 meters long, it will complete three floors and will be able to accommodate 300 to 400 workers. He will first receive the boxes, which are, it seems, a little cramped, in the premises they currently occupy. A few other workshops will also be opened up and certain workshops will be set up in the factory which, for lack of space at home, the Longines had to successively set up in the village. The new factory will be under roof during the course of June. As soon as it can be occupied, the oldest will be demolished, that which was the cradle of the great manufacture and which makes a very modest figure compared to the recent additions which surround it, and it will be rebuilt according to the principles the most modern allowed in this type of building.

Once these works have been completed, the Longines factory will extend over a length of 200 meters, in an uninterrupted line of buildings. It will then luge a veritable army of workers, approximately 1,500 workers.

La Fédération Horlogère Feb 21, 1916

Our great factory, which already has an impressive number of 25, 40 and 50 year olds, had the pleasure of celebrating one of its directors yesterday. Mr. Alfred Pfister, managing director and technical director, in fact completed, on June 5, his fifty years of activity at the Compagnie des montres Longines.

In the morning, during a very intimate ceremony, the Board of Directors expressed its jubilee congratulations and best wishes and presented him with a souvenir to mark this important milestone.

In the evening, a dinner offered in his honor brought together Mr. Pfister’s family surrounded by members of the Board of Directors and Management, workshop managers and the main department heads of the technical and commercial departments. A festive atmosphere never ceased to reign during this charming ceremony, various speeches were made, in particular by the Chairman of the Board of Directors, MM Savoye, who was able to describe in concise terms the extraordinary career: active and beneficent of Mrs. Pfister at the Longines factory. Joined in 1896 as a technician, he was soon the highly appreciated collaborator of Mr. Jacques David, of whom he was the designated successor on the latter’s death in 1912. Appointed technical director in 1915, Mr. Fister became managing director in 1927 , while retaining his duties as technical director.

During this long period of tireless activity, he ceased to put his exceptional qualities at the service of the great manufacture and he contributed to a very large extent to the development and constant improvement of Longines products and quality. . Apart from his absorbing work at the factory, Mr. Pfister also played an important role in the watch associations. He is a founding member of the Fédération Horlogère and of the Bernese Cantonal Association of Watch Manufacturers. Mr. Fister has also been the very competent and dedicated president of the Saint-Imier watchmaking school for many years.

We associate ourselves with the many congratulations that have reached the happy jubilee and hope that he may still enjoy the beautiful vitality that has devolved to him for a long time to come.

La Fédération Horlogère Jun 13, 1946

Death of Mr. Alfred Plister Managing Director and Technical Director of Longines

From our St-Imier correspondent:

Mr. Alfred Pfister, managing director and technical director of the Compagnie des Montres Longines, has just died at the age of 77, struck by an embolism on September 17, 1951 in Lausanne, the city in which Mr. Pfister had fixed his residence since the end of December 1948, and from where, every week. it came back to Longines.

This sad news caused, in Saint-Imier, the surprise and the emotion that one can guess, because nothing let foresee it. Indeed. Benefiting from a robust constitution, always alert and of great vitality, Mr. Alfred Pfister went about his business regularly.

Born in Le Locle on November 18, 1874, the deceased was able to give the Longines manufacture the benefit of his qualities as an organizer and innovator throughout the last 55 years. Registered in the rolls of the Longines factory on June 5, 1896, at a time when the watchmaking industry was about to take on a decisive development, Mr. Pfister brought to the company his talents as a technician trained by the best masters. After the Watchmaking School in Le Locle, where, with two comrades, he had obtained the first diploma from the Neuchâtel schools, he worked for a few months with his father, a manufacturer of complicated parts. An internship in another factory preceded his entry into Longines. Appointed authorized representative in 1912, Mr. Pfister took over the reins of the technical department after the death of Mr. Jacques David, the partner of Mr. E. Francillon, founder of Longines. On May 10, 1915, the Longines factory, transformed into a public limited company. appointed technical director. His rise was not to stop there. In 1918, he became a member of the Board of Directors and, in 1927, Managing Director.

On January 17, 1924, the Watch Federation was created in Neuchâtel. The setting up of this group was the culmination of efforts undertaken for a long time to put an end to chablonnage and clean up selling prices. These two conditions absolutely had to be met so that the watch industry did not run into ruin. As a representative of the Fabrique des Longines on the committee of the Watchmaking Federation, Mr. Pfister contributed to the development of watchmaking conventions. He has spared no effort to ensure that these do not remain a dead letter, but on the contrary, become a useful instrument enabling our industry to sell its products.

For more than half a century Mr. Pfister’s influence has been felt continuously. The watch industry in general, the Fabrique des Longines in particular, the Saint-Imier Watchmaking School, followed his directives and profited from his experience. The efforts which Mr. Pfister has deployed in the modernization of manufacturing processes and the adoption of new methods, the personal part which he has taken in the reorganization of the watch industry, are meritorious.

A prominent figure in the city, M Alfred Pfister presided over the Commission for the School of Watchmaking and Mechanics with uncontested authority from 1916 to 1922 and from 1928 until death struck him down.

All questions of a technical nature held no secrets for Mr. Alfred Fister; this is why the deceased sought and made himself effectively useful also to the Technical Services Commission. For five years, from 1903 to 1908, Mr. Pfister was a listened and informed member.

The death of Mr. Alfred Pfister, which constitutes an obvious loss for our city, will be painfully felt in our great local manufacture of Longines watchmaking.

May his family, so suddenly and painfully waiting in their dearest affections, please find here the expression of our deep and sincere sympathy.

l’Impartial Sep 19, 1951

Auguste Agassiz

Auguste Agassiz was born on April 15, 1809 near the village of Mont-Vully. He was the son of Louis Benjamin Rudolphe Agassiz, pastor, and Rose Mayor, and brother of famed scientist Louis Agassiz. He married his cousin Julie Louise Henriette Mayor, daughter of François Auguste Mayor, a banker. After apprenticing as a banker at Mayor-Fornachon in Neuchâtel, Auguste moved to Saint-Imier in 1832 to found his watchmaking business the following year. His first watches exported to the United States were distributed by his partner in New York, his cousin Auguste Mayor.

Auguste Agassiz became President of the municipality of Saint-Imier in 1846 but retired for health reasons to Lausanne and handed his company over to his nephew, Ernest Francillon in 1854. His son Georges Agassiz later started another watchmaking business in Saint-Imier, Agassiz Fils. Auguste moved to Lausanne for the more moderate climate and died on February 25, 1877.

The only mention I could find of the death of Auguste Agassiz in primary sources was the announcement reproduced at right. This is a surprise, given his stature as a watchmaker and importance to the Saint-Imier valley overall.

We would like to correct an oversight, and to mention the death of Mr. Auguste Agassiz, former mayor of St-Imier, who died on Sunday in Lausanne, after long years of suffering. He had been one of the most active and intelligent promoters of the watch industry in the Jura, and the benefactor of the Courtelary district hospice.

Feuille 1877-03-03

See Also: Auguste Agassiz

Agassiz Fils

Contrary to many reports, the Agassiz family continued in business, producing their own watches in Saint-Imier, even after Ernest Francillon launched his company. Georges Agassiz (born January 31, 1846) was the son of Auguste Agassiz and studied science at the Collège Galliard in Lausanne before marrying the American Cécile Eugénie Eilshemius while doing scientific work in the United States under his uncle Louis Agassiz. He worked at the Longines factory under Ernest Francillon in 1870 and started his own company, Agassiz Fils, in 1876.

Agassiz Fils used a fish as their logo, as seen below, and this holds the distinction of being the first watch-related brand or trademark approved by the Swiss commission! Georges Agassiz retired in 1895 to Lausanne and later focused on entomology. He died on July 15, 1910.

Once they began processing trademark approvals, the Swiss government processed the initial batch of applications in alphabetical order. Thus, Agassiz Fils was given the lowest sequential trademark number (22) of any watchmaking entity. Most of these early trademarks lapsed or are no longer in business, with Longines being one of the few still in use. But there are some other familiar names in that first “class” of trademarks, including L. Audemars (predecessor of today’s Audemars Piguet), Fabrique d’Horlogerie de Fontainemelon and Fabrique d’Ebauches Cortébert (both part of today’s ETA), LeCoultre & Co. (today’s Jaeger-LeCoultre), G. Thommen (forerunner of Revue Thommen), Fritz Bovet and Albert Bovet (namesakes of today’s Bovet 1822), Chs-F. Tissot & Fils (today’s Tissot), and Girard-Perregaux.

Of these, only Longines retains the exact name and logo image from April 1882. Tissot and Girard-Perregaux in particular have a solid claim to a tie for longest-running brand, but Tissot did not register a logo mark and Girard-Perregaux no longer uses the complicated eagle and anchor mark registered then.

See Also: Georges Agassiz

Ernest Francillon

Ernest Francillon was born on July 10, 1834 in Lausanne. He was the son of Mark Francillon, an iron merchant, and Olympus Agassiz. After attending Galliard College in Lausanne, the Sillig Institute in Vevey, and business school in Stuttgart, he entered an apprenticeship as a watchmaker in Môtiers. He married Ida Grosjean, daughter of Etienne Grosjean, a pastor in Court.

Ernest Francillon joined his uncle Auguste Agassiz’ watchmaking business in Saint-Imier and took it over in 1854. In 1866 he established the Longines factory.

Francillon was a member of the Bernese Grand Council from 1878 through 1882, was a radical national councillor from 1881-1890, and was the first President of the General Council of Saint-Imier in 1887.With his friends Albert Gobat, Pierre Jolissaint, and Eduard Marti, Francillon developed the railway network to support the watch industry in the Bernese Jura. He was also the Chairman of the Board of Directors for the Jura-Berne-Lucerne railway from 1871 through 1888 and Vice President of the Jura-Simplon railway from 1890 through 1890. He also served as a customs specialist for the Swiss National Council, focusing on the development of international trade.

Francillon died on April 3, 1900 in Saint-Imier.

See Also: Ernest Francillon

Tuesday evening, a telegram announced the death of M. Ernest Francillon, kidnapped in three days by an attack of influenza.

La Fédération Horlogère, April 5, 1900

The disappearance of this man, who played an important role in several areas of our national existence, will be painfully felt by all those who knew and loved him.

We will leave it to others to trace what Ernest Francillon’s political role was. Within the framework of our newspaper, of which he was one of the friends of the first hour, we will recall that, chief of one of the most considerable and most justly renowned industrial establishments of the Jura, he carried the flag of Swiss watchmaking on the world market and that the story of its mason is linked to that of the universal exhibitions, where it commands the highest rewards.

Ernest Francillon was, in every sense of the term, a gentleman.

An indefatigable worker, a quick and lucid mind, having a fair and quick conception of things, and knowing marvelously well the conditions and needs of our watchmaking industry, he rendered real and precious services wherever he went.

One of the founders and the first member of the Central Committee of the Intercantonal Society of Jura Industries, of which he was on his death the first vice-president, he devoted the best of his activity and his high competence to this society.

He was to chair, today, the constituent assembly of the Swiss Chamber of Watchmaking.

Ernest Francillon goes away, in his sixty-sixth year, following for a few months in the grave, the son he mourned.

Unanimous regrets will accompany to his final resting place this good citizen, this good man, whom cruel fate takes away from us too much and who will leave the example of a whole life of honor, intelligent work and devotion to public affairs.

We offer to the so painfully tried family of this friend, the expression of our respectful condolences.

We announced in a few lines, in our previous issue, the death of one of the most outstanding personalities of the Swiss watch industry, Mr. Ernest Francillon. Today, we have the sad duty to dedicate a more developed biographical note to him.

Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie, May 1900

Ern. Francillon was of Vaud origin. Born in Lausanne in 1834, he did all his studies there, then he entered the watchmaking factory of his uncle Agassiz, in St-Inner, where he was to create the Longines factory in 1866, and win for it the reputation it currently enjoys worldwide. He was the first to introduce mechanical watchmaking to the Bernese Jura, and thus the canton of Bern became his adopted homeland.

The establishment of which he was the head, already mentioned many times in our columns on the occasion of numerous exhibitions where he obtained the highest awards, can be considered as a model of its kind and is among the most prosperous in Switzerland.

Moreover, industry did not prevent Francillon from dealing with the general interests of the country: he was in particular a member of the municipal council of St-Imier, president of the Intercantonal Society of Jura Industries, of the former Compagnie du Jura-Bern-Lucerne and Jura-Simplon railways, member of the Bernese Grand Council, member of the National Council for eight years, lieutenant-colonel in the federal army, etc. He took an active part in the elaboration of various commercial treaties, the law on patents and the law on the control of gold and silver materials.

Last August, the death of his only son, caused by a cruel accident which we have reported, dealt him a blow from which he was never to recover. It was carried away in a few days On Friday, March 30, he was still interested in the visit of a certain number of people who had been invited to show them the products intended for the Paris exhibition, and whose, obliged to keep the room, he regretted not being able to do the honors himself, but no one at the time suspected that four days later he would succumb to infectious angina from which the attack of influenza from which he was suffering was to worsen.

Francillon was honorary president of the Bernese cantonal shooting which will take place this year in St-Imler; the Municipal Council of this locality has decided to give him an official funeral, worthy crowning of a life of persevering work and dedication

patriotic.

Jacques David

Jacques David was born March 18, 1845 in Lausanne, son of Maurice Louis David, an industrialist. He attended the Ecole Centrale des Arts et Manufactures in Paris and married Marie Guiral, daughter of Jean Théophile Gabriel Guiral, director of a weaving factory in Saint-Quentin.

Jacques David participated in the establishment of the Longines factory in 1866 before his apprenticeship as a watchmaker in Le Locle for a short time. He returned to Longines and became a manager of the company in 1880 and a partner in the business with Ernest Francillon in 1890.

Like Francillon, David was involved in industry and local politics, becoming Vice President of the Swiss Union of Watch Factories and a member of the Swiss Watch Chamber. He was also a Municipal Councillor from 1886 through 1893, General Councillor of Saint-Imier from 1899 through 1912, and Radical Deputy in the Bernese Grand Council from 1902-1912.

Jacques David died on September 12, 1912 in Bern.

See Also: Jacques David

Théodore Gribi’s Report

I have located a complete copy of Théodore Gribi’s report from Philadelphia that set everything in motion. It was early, and focuses on the delivery and display of watches from Switzerland and concerns of shipping, customs, and protection of their samples from theft. But Gribi finishes with a vague but dire warning for his colleagues at home. Below is my translation of the two paragraphs that inspired Jacques David’s trip and the creation of Longines!

Over the past few days, as an expert for the jury, I have visited the products and tools of the watchmaking factory in Waltham (Massachusetts), and I have been in awe, I must admit, in examining either the watches of different kinds and qualities, or the magnificent machines and tools which this factory has exhibited. It must be recognized that we have allowed ourselves, in many respects, to be overtaken by our competitors in the New World, and any Swiss manufacturer who comes here to find out about this point, without prejudice, will be convinced of it immediately.

Excerpted from Théodore Gribi’s Report from the Philadelphia Exhibition of 1876

It is therefore essential, in my opinion, if we do not want to allow ourselves to be deprived of the monopoly of the watch trade, not only in America, but in the rest of the world, and even in Europe, where the Americans will certainly come to make us competition, to take care together and by mutual agreement of a serious reorganization of our Swiss manufacturing system, with a view to supplying products of better quality, and which will gradually restore the badly compromised reputation of our watchmaking in this country, as a result of the poor quality merchandise that was shipped there in such large quantities.

This is a question which deserves the full attention of the industrialists and merchants of our country who are concerned about the future of our beautiful industry, and wish to keep it in its cradle, and it will be with pleasure that I will put at their disposal, after my return to Switzerland, the knowledge and experience that I will have acquired during my current stay in the United States.

Gribi remained in the United States after this, and was responsible for a similar report from the Chicago Exhibition in 1893. His conclusions there are puzzling, designed perhaps to reassure his Swiss colleagues rather than warn them of progress:

Certainly the watch industry is firmly established in this small territory of western Switzerland, both in the Neuchâtel, Bernese and Vaudois Jura and in Geneva, and it will never lose its prestige, whatever the competition that will be made to him abroad.

Excerpted from Théodore Gribi’s report from Chicago in 1893

Gribi remained in the United States and went to work for American watchmaking firms. His lessons on watch finishing were “must read” for turn of the century watchmakers and he wrote copiously in Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie in those years.

Alfred Pfister

Alfred Pfister’s important work as technical director and head of Longines is well documented, though he is overshadowed by his predecessors, David and Francillon. Still, he presided over some of the most important moves for the company, notably its expansion through the 1920s and 1930s.

Death of Mr. Alfred Pfister Managing Director and Technical Director of Longines

l’Impartial September 19, 1951

From our St-Imier correspondent:

Mr. Alfred Pfister, managing director and technical director of the Compagnie des Montres Longines, has just died at the age of 77, struck by an embolism on September 17, 1951 in Lausanne, the city in which Mr. Pfister had fixed his residence since the end of December 1948, and from where, every week, he came back to Longines.

This sad news caused, in Saint-Imier, the surprise and the emotion that one can guess, because nothing let them foresee it. Indeed, benefiting from a robust constitution, always alert and of great vitality, Mr. Alfred Pfister went about his business regularly.

Born in Le Locle on November 18, 1874, the deceased was able to give the Longines manufacture the benefit of his qualities as an organizer and innovator throughout the last 55 years. Registered in the rolls of the Longines factory on June 5, 1896, at a time when the watchmaking industry was about to take on a decisive development, Mr. Pfister brought to the company his talents as a technician trained by the best masters. After the Watchmaking School in Le Locle, where, with two comrades, he had obtained the first diploma from the Neuchâtel schools, he worked for a few months with his father, a manufacturer of complicated parts. An internship in another factory preceded his entry into Longines. Appointed authorized representative in 1912, Mr. Pfister took over the reins of the technical department after the death of Mr. Jacques David, the partner of Mr. E. Francillon, founder of Longines. On May 10, 1915, as the Longines factory transformed into a public limited company, he was appointed technical director. His rise was not to stop there. In 1918, he became a member of the Board of Directors and, in 1927, Managing Director.

On January 17, 1924, the Watch Federation was created in Neuchâtel. The setting up of this group was the culmination of efforts undertaken for a long time to put an end to chablonnage and clean up selling prices. These two conditions absolutely had to be met so that the watch industry did not run into ruin. As a representative of the Fabrique des Longines on the committee of the Watchmaking Federation, Mr. Pfister contributed to the development of watchmaking conventions. He has spared no effort to ensure that these do not remain a dead letter, but on the contrary, become a useful instrument enabling our industry to sell its products.

For more than half a century Mr. Pfister’s influence has been felt continuously. The watch industry in general, the Fabrique des Longines in particular, the Saint-Imier Watchmaking School, followed his directives and profited from his experience. The efforts which Mr. Pfister has deployed in the modernization of manufacturing processes and the adoption of new methods, the personal part which he has taken in the reorganization of the watch industry, are meritorious.

A prominent figure in the city, Mr. Alfred Pfister presided over the Commission for the School of Watchmaking and Mechanics with uncontested authority from 1916 to 1922 and from 1928 until death struck him down.

All questions of a technical nature held no secrets for Mr. Alfred Fister; this is why the deceased sought and made himself effectively useful also to the Technical Services Commission. For five years, from 1903 to 1908, Mr. Pfister was a listened and informed member.

The death of Mr. Alfred Pfister, which constitutes an obvious loss for our city, will be painfully felt in our great local manufacture of Longines watchmaking.

May his family, so suddenly and painfully waiting in their dearest affections, please find here the expression of our deep and sincere sympathy.

Fritz Galley

Much of what I know about Fritz Galley, who led Longines from 1951 through 1964, came from this obituary in Europa Star.

Fritz Galley, technical director

Europa Star 27, 1964

Mr. Fritz Galley, technical director at the Compagnie des Montres Longines, has just suddenly disappeared, the victim of a heart attack. He was 53 years old.

Born in Cernier on January 5, 1911, Fritz Galley attended the schools of his village, then entered Technicum in La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1926. He was to leave this institution in 1930, with the diploma of technician-watchmaker. After more or less long in several companies in the watchmaking field (Fabrique d’horlogerie de Fontainemelon, Fabrique de Pignons Hélios in Bévilard, Manufacture des Montres Tissot in Le Locle), he was hired by the Compagnie des Montres Longines on September 3, 1951 where, very quickly, he occupies a prominent position. The sudden disappearance of Mr. Alfred Pfister, Managing Director and Technical Director of the Company, caused a number of reorganization measures. From then on, Mr. Fritz Galley was appointed authorized representative in 1952, and technical director on January 1, 1953.

At the factory, Mr. Fritz Galley did not fail to take an interest in all the duties of his charge. At a time when technical progress was progressing by leaps and bounds, or the development and equipment of a company demanded attentive care, he took on the tasks inherent in the expansion of the factory, the extension and to the creation of new branches. If Fritz Galley is no more, the imprint of his personality remains in his works. He leaves behind him many achievements, the fruit of constant hard work, during the thirteen years he spent at Longines.

Mr. Fritz Galley has sat on numerous commissions belonging to watchmaking associations. Ten years ago, he took a large part in the creation of the G.E.T. (Grouping of Technical Studies). He was one of the pros. engines of the most active of the C.T.M. (Technical Control of Watches), its supervisory commission, its administrative delegation and its opposition delegation. He closely followed the work of the Swiss Watch Research Laboratory. Last year, the Swiss Society of Chronometry called him to its presidency. He also belonged to the Patronage Committee of the 1964 International Chronometry Congress.

I found your site while researching an envelope mailed from Brazzaville, French Congo, in October 1917 to Fabrique des Longines, Francillon & Cie. SA, Saint Imier, Suisse. It was sent as registered mail and censored by the French.

Your history of the company is fascinating. Thank you for taking the time to research this and post it on line. I often remark how the internet drags me into rabbit holes that 30 years ago didn’t exist. This is one that I greatly enjoyed.