Today, a “Lépine” movement is one with small seconds opposite the crown. But this is not one of the many innovations we should associate with Jean-Antoine Lépine, one of the greatest watchmakers of all time. Watchmaker to King Louis XV and George Washington, Lépine changed the course of watchmaking forever, with his plate-and-bridges movement design still used today. So why do we contrast “Lépine” movements with “savonnette” or “hunter” and what’s all this about small seconds?

Lépine, Savonnette, and Hunter

It is commonly assumed today that a Lépine watch or movement has the stem opposite the small seconds subdial and a savonnette or hunter movement has the subdial 90º off-axis. If the crown is at 3:00 (as is common on wristwatches), this places the small seconds subdial at 9:00 for Lépine watches and at 6:00 for savonnette or hunter watches.

But as we shall see, this is by no means universal and has almost nothing to do with the origin of these terms. Indeed, Jean-Antoine Lépine’s movement had no stem and could be oriented in any direction, and the terms savonnette and hunter could apply to any movement as well. But the above definition is most widespread in modern times, if it is known at all.

How Jean-Antoine Lépine Transformed Watchmaking

Before Jean-Antoine Lépine, there were no watches, just small portable clocks. After his career as watchmaker to French King Louis XV, every fine lady or gentleman wanted a watch in their pocket. His new design transformed the shape of the watch, the process of manufacturing, and the very organization of the watch industry itself. Almost every watch produced over the past century and a half could legitimately be called “Lépine” in its basic design, yet today the term is usually used to refer to the fairly uncommon practice of locating a small seconds subdial at 9:00. Let’s unpack all this.

Jean-Antoine Lépine was born near Geneva in 1720 and moved to Paris, where his work brought him life-long fame. He married a daughter of watchmaker André-Charles Caron and became his business partner. He also became part of Caron’s family, including brother in law polymath Pierre-Augustin “Beaumarchais” (a watchmaker who funneled French money to American revolutionaries and wrote the Figaro plays) and sister in law artist Marie-Josèphe.

Lépine invented an entirely new way of constructing a watch on a single main plate, dispensing with the fusée and chain and placing the balance on the same plane as the wheel train. Rather than sandwiching the wheels between two plates separated by pillars, Lépine screwed bridges and cocks to the main plate. This allowed for much slimmer watches, improved durability, and made assembly and maintenance easier. The invention was credited for giving French watchmakers an advantage over the then-dominant of English in the mid 19th century.

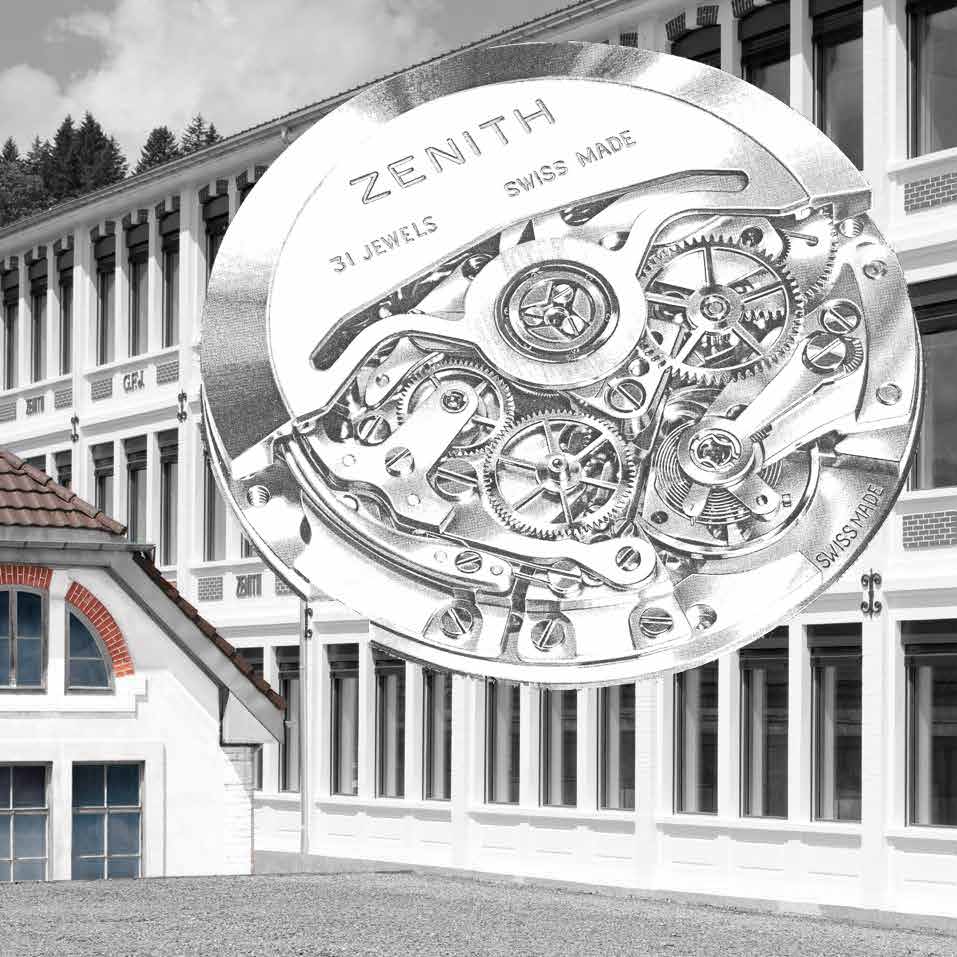

Lépine’s arrangement of the wheel train was widely adopted, and the machined main plate became the critical component in watchmaking. Soon, Frédéric Japy established his ebauche factory in Beaucourt, seeding a few basic wheel arrangements to nearly every 19th century watchmaker. This system of wheels and bridges affixed to a main plate was known at the time as “Lépine” and remains in use today.

Another Lépine invention was equally important. Rather than a Fusée and chain, Lépine used a spring barrel with teeth that meshed directly with the wheels of the movement. Force was regulated by a specially-shaped mainspring rather than the chain, a simplification we continue to rely on today.

Lépine continued to innovate throughout his life. He created mechanisms for minute repetition, perpetual calendar, moon phases, and even keyless winding and dead-beat seconds. Although he lived to the age of 94, becoming watchmaker to the king (and George Washington) and pen-pal to Voltaire, Lépine’s personal story is not well known since his biography was lost during the French Revolution (see below).

Lépine and Savonnette

Even though nearly every modern watch movement is built on Lépine’s revolutionary ideas, his name is usually associated today with an unintended by-product of his design. Although Lépine considered various ways to dispense with the winding key, the stem and bow were not connected to the watch movement in his time. Thus, his design does not require that the seconds hand be placed opposite the stem.

Most watches using Lépine movements were “hung” from a chain or ribbon with the bow on a stem at 12:00 on the dial. For aesthetic reasons, if a watch was equipped with a seconds hand, it was usually positioned opposite the stem at 6:00. This style of watch, with the stem and bow at 12:00 and small seconds subdial at 6:00, became associated with Lépine’s name, even though the arrangement was not a technical feature of his movements.

Around the same time, so-called “savonnette” style watches emerged. These were designed to be held in the hand like a bar of soap (“savonnette” in French) with the stem resting against the thumb at 3:00. Even after the crown became a functional part of the watch (first as a cover release and later for winding and setting the hands), watchmakers continued to produce both “Lépine” and “savonnette” movements with small seconds at 6:00 and stem at 12:00 or 3:00, respectively. Many of these are closely related, as with the famous Unitas 6497 and 6498, and most ebauche makers produced both styles.

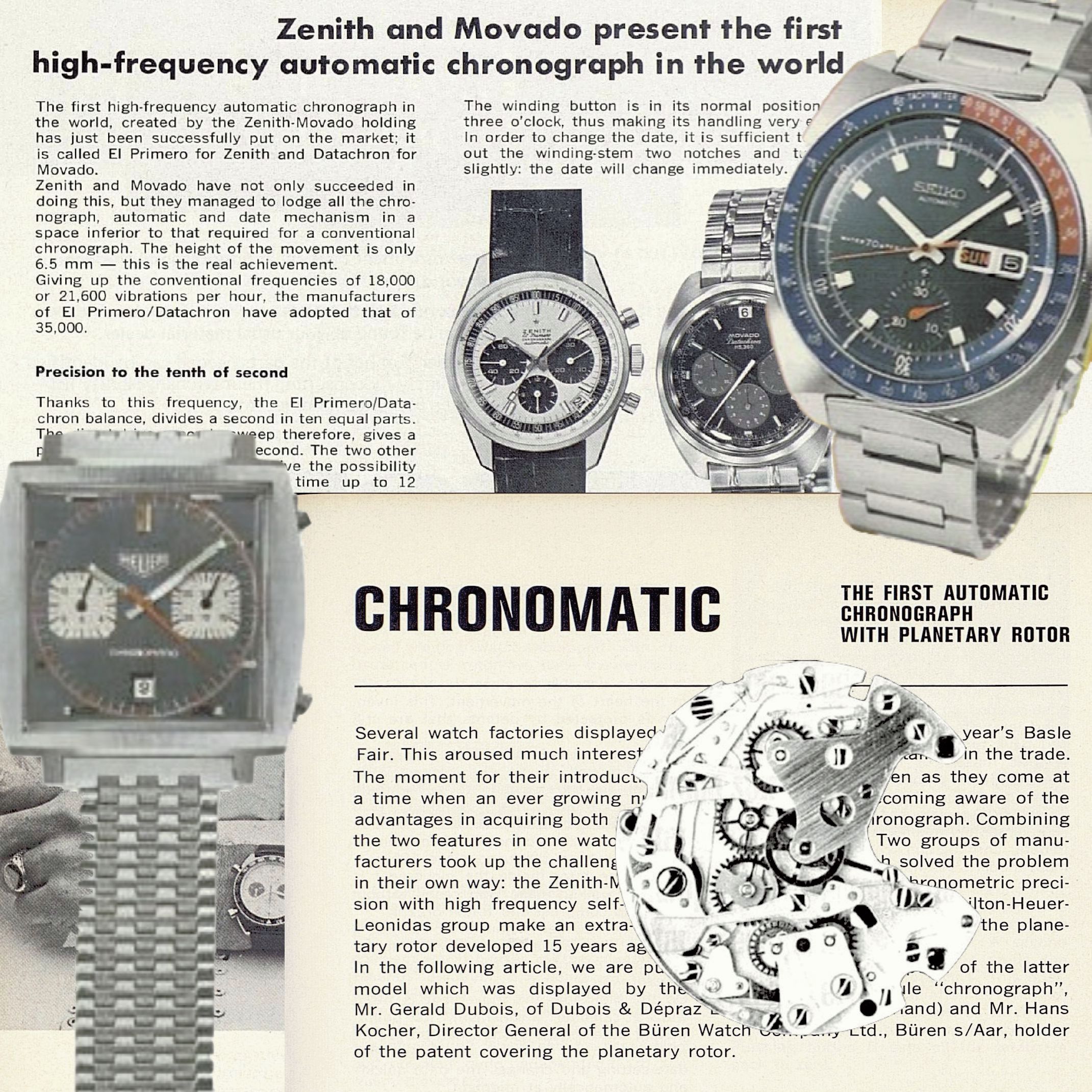

Once pocket watches gave way to wristwatches, the 90º off-axis “savonnette” movement was prized due to the more symmetrical positioning of the small seconds at 6:00 on the dial. The “Lépine” design, with small seconds at 9:00 on the dial of a wristwatch, is typically only found on chronographs and other complicated watches with other subdials today. Indeed, chronographs with small seconds anywhere else are quite rare.

In contrast, it is rare to see a time-only movement with small seconds at 9:00 in modern watches. A few exceptions include the afore-mentioned Unitas (ETA) Cal. 6497, Zenith’s Elite Cal. 680 and 690, a few oddballs like Seiko’s Cal. 8L34 and Cal. 9S63, and Valjoux 7750-derived movements like Naoya Hida‘s NH Type 1.

What is a Hunter Watch?

Most early pocket watches featured an exposed dial, with a glass crystal that could be opened to manually set the hands. Later, a pusher in the case or lever alongside the dial changed the function of the crown from winding to setting. Many watches also featured “secret” springs an hidden catches, releasing a solid cover for the back or dial.

This gave rise to the so-called “hunter” style of watch, with a button in the stem to release the cover of a savonnette style watch. These were so popular in the United States that “hunter” became a synonym for “savonnette”, with both referring to a watch with the small seconds subdial 90º from the stem or crown.

The evocative term proved to be great marketing once it was adopted in the United States around 1900. Although this style of watch appears to have originated in Turkey and has more to do with durability and dust protection than aesthetics, the term “hunter” caught the public imagination. For most of the 20th century, watchmakers produced “hunter” or “hunting” watches with engraved scenes of stags, dogs, and hunters on horseback. Most buyers probably never associated the location of the small seconds subdial with the term, and indeed many such “hunting” watches in later years have central seconds or none at all. Some even have the crown at 12:00!

Image: Europa Star 125, 1981

A quick survey of 19th century pocket watches reveals that there was much variation in this period as well. Many so-called Lépine watches had covers, some of which were spring-loaded and featured carved decoration. Many lacked a small seconds hand as well, and some were oriented in other ways. But even in the 19th century, the terms Lépine and savonnette were widely used to indicate the position of the small seconds subdial relative to the stem.

The Grail Watch Perspective

The placement of small seconds opposite the stem has little to do with Lépine, so it is odd that his name is most closely associated with this design. It is equally odd that this arrangement, which was chosen for visual harmony in pocket watches, is so unusual once the stem is rotated to 3:00 in a wristwatch. Lépine should be remembered for inventing the plate-and-bridges movement concept, the modern spring barrel, his mechanical complications, and his notable life!

From the Mrs. George A. Hearn collection, 1907

References

Lépine’s Biography, 1879

The following biography of Jean-Antoine Lépine was published in Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie’s second issue of 1879. It is credited to Father Lépine, vicar-general of the bishopric of Gap, and refers to an incomplete autobiography written by Lépine but lost during the French Revolution. This article is especially interesting because it represents a very early account of a figure whose life is not otherwise well-documented. I present below my English translation of the original French article.

Biography

One of our foreign subscribers had, some time ago, asked us for information on the watchmaker Lépine, of whom he then had in his hands a watch with a ratchet gear. We found on this occasion that the details of the life of this eminent watchmaker are practically nil in the works on watchmaking. However, our research led to the following biography, due to the kindness of a member of his family, Father Lépine, vicar-general of the bishopric of Gap, a biography which we are happy to put before the eyes of our readers.

LÉPINE

Lépine (Jean-Antoine), famous watchmaker, was born in Challex, in the Pays de Gex (part of the department of Ain, located on the south-eastern slope of the Jura), on November 18, 1720. From his childhood, the young Lépine showed a talent for mechanics. He made rapid progress under the direction of Mr. Decrose, manufacturer of watches in Saconnex (a village within Geneva but located 3 kilometers from Ferney-Voltaire in France). At the age of 24, he left for Paris, and was quickly noticed there for his work. The king’s watchmaker, Mr. Caron, father of the famous Beaumarchais, wanted to have him as a partner and gave him his daughter in marriage. This establishment provided Lépine with the means to follow through on his inventions and perfect his art, and the watches associated with his name produced a veritable revolution in watchmaking. He removed the fusée which the chain is wrapped around when the watch is wound, replacing this with teeth around the barrel, and thus both greatly improved and simplified the winding works. But by removing the fusée, which regulated the force of the spring, Lépine saw that his watch was going too quickly as soon as it was wound, and that it would slow down as the spring relaxed. He remedied this inconvenience by constructing a whip spring, that was weaker in the front part than in the centre, thus equalizing the force, and by means of his escapement, he obtained more regular power. This invention enabled him to make watches of a flatter shape, and to reduce them to such a small volume that one could adorn a ring with them. It was Lépine’s design that made French watchmaking superior to that of England.

The reputation of Lépine spread to the four corners of the earth along with his watches. In 1770, he had the honor of presenting to Louis XV a so-called astronomical repeater, which had only been done on pendulum clocks, with a perpetual calendar of his own invention. The king named him his watchmaker. Lépine invented various deat-beat seconds mechanisms, which had previously not been accomplished because the balance operated too slowly causing the time to vary when carried in the pocket. Lépine’s ingenious mechanism used a rectilinear ratcheting pinion to compensate for this. These gears offer less friction, and therefore the mechanism does not lose strength. This method has now been abandoned, a loss to watchmakers who see the advantages of such a system.

Lépine also made very complicated clocks, marking the date and phases of the moon, furnished with sets of flutes, and which ran for a year without being wound. We see from his account books that he sent these to various courts in Europe, with the court of Spain paying sixty thousand francs for one and eighty thousand francs for another. Voltaire, who had attracted part of the Lépine family to his workshops in Ferney, maintained a long correspondence with him on the various branches of watchmaking. Lépine’s letters can be found in some editions of the works of Voltaire.

Although Lépine had written about watchmaking, he was more comfortable handling a file than a pen and knew the mechanism of a watch better than the French language. Therefore, he asked the teacher of his children, an abbot, to proof-read and correct his biography. But the work was never printed, either because Lépine almost entirely lost his sight several months before his death, or because he lacked the funds to print it due to the expense of his experiments and his inventions. The manuscript was lost at the proofreader during the Revolution. Although he was now blind, Lépine imagined a new escapement and asked one of his grand-nephews, Jacques Lépine, was appointed watchmaker to the King of Westphalia in 1809, to help him construct it. But the elder Lépine died on May 31, 1814 before Jacques returned to Paris.

Note: The community of Challex had many watchmaking workshops and still supplies a large number of distinguished workers to the establishments in Geneva today. J.-J. Rousseau had learned watchmaking at Challex. The tradition reports that after a few months of apprenticeship, he had succeeded in making a piece worthy of a student of several years, and that, having presented it to his father, the latter made little of it. Young Jean-Jacques, piqued by this disdain, decided to leave the trade to devote himself to studies, and retired to Annecy, where he was welcomed by Madame de Warrens.

Leave a Reply