Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel, died on March 24, 2023. Although many touching tributes are currently being published to this titan of the technology industry, most overlook what Moore himself called his greatest mistake: Intel’s attempt to corner the digital watch business. Intel bought Microma, a hot Silicon Valley startup, in 1972 but gave up the business just six years later. Moore continued to wear his “$15 million watch” for decades as a reminder of this failure – and to stay out of consumer products!

Credit: Intel Corporation

Quartz Watches and Integrated Circuits

Image: Europa Star Eastern Jeweler, 113, 1969

The development of the integrated circuit is one of the most important advancements of the 20th century, and no company deserves more credit for it than Intel. But few are aware that this technology was driven in the earliest days by a need for low-powered electronics for watches.

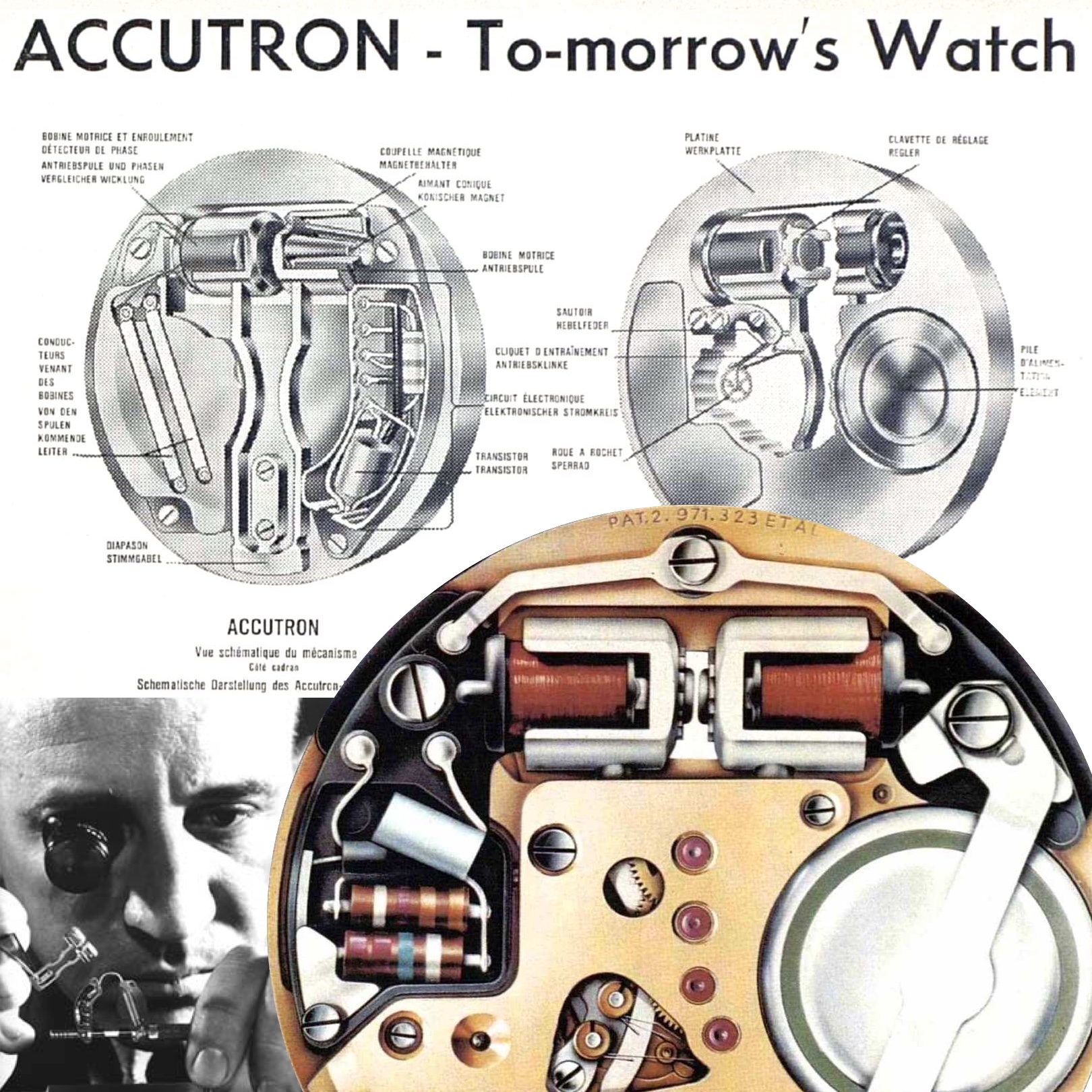

Some of the earliest digital electronic products were watches. I have previously written about electric watches and the earliest quartz watches, including a look at the ill-fated Longines Ultra-Quartz for Europa Star. Quartz crystals oscillate at a predictable frequency, so they can be used to keep the time by counting these vibrations and advancing a hand or counter once so many have passed. But they vibrate 8,000 or more times per second, so even a primitive digital counter needs quite a few components. By far the biggest obstacle to a practical quartz watch was the cost and power draw of these transistors, resisters, and capacitors. An integrated circuit brings these components together and CMOS technology dramatically reduced power consumption.

Contrary to contemporary folklore, the Swiss were not taken by surprise by quartz and electronic watches. Swiss scientists and engineers were closely involved in the development of the integrated circuit, and the Centre Electronique Horloger (CEH) under Roger Wellinger brought Kurt Hübner and others home to develop the technology in Switzerland. CEH produced the first quartz watch and the first low-voltage CMOS chip, and Swiss quartz movements were as technologically advanced as anything produced in the United States, Japan, or Germany.

But the Americans were building an entire industry around the integrated circuit, spurred by Department of Defense funding. A co-founder of Fairchild Semiconductor, Swiss physicist Jean A. Hoerni, created a new company in Cupertino, California called Intersil to produce custom chips, including low-powered CMOS counters for watches. He worked closely with Omega and Seiko, and quartz watches with Intersil ICs were obviously superior to the competition.

Microma Universal

The market opportunity for electronic components in the watch industry was obvious. Sensing opportunity, Microma Universal was incorporated in Mountain View, California on December 30, 1970. The “Universal” part of the name refers to Universal Perret Frères SA of Genève, the parent company of famed watchmaker Universal Genève. This Swiss-American company was dedicated to developing electronic components to serve the watch industry.

Image: Europa Star Trade Bulletin 718, 1972

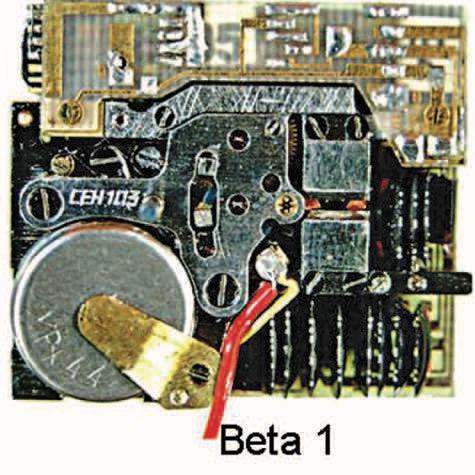

Microma’s first product was the EWC-1000, an integrated circuit chip containing an oscillator, a binary frequency divider, a pulse control, and a motor power compensator. Introduced in mid 1971, it supported frequencies from 8 KHz to 128 MHz and pulled just 10 micro amps from a 1.35 V battery. The company quickly packaged this into a module containing a quartz crystal and other components required to build a watch. The QTM-0001 could be attached to a conventional watch movement, converting it to analog quartz.

But Microma had another project in the works. Another joint Swiss-American firm called Optel had created a practical dynamic scattering LCD display and was working with the SSIH to bring it to market in digital watches from Waltham, Titus, Rodania, and others. Texas Instruments created a similar display technology, and this was used by Ebauches SA in a radical model from Longines. These were “dynamic scattering” LCDs but another technology known as Field Effect was developed in Ohio by Ilixco and the CEH and was used by Gruen. Microma had developed their own LCD watch using a display produced by Hamlin in Wisconsin, and the company planned to build a complete watch around their integrated module.

Intel, Microma, and the LCD Digital Watch

Gordon Moore at Intel was impressed by the Microma concept, seeing digital watches as another market for Intel. On July 14, 1972, Intel purchased Microma for $15 million and soon moved the firm from Mountain View to nearby Cupertino, home of Intersil and now familiar for Apple’s headquarters.

Rather than being simply an “arms supplier” for other watchmakers, Intel decided to launch Microma as a maker of complete watches. In October 1972, a line of Microma LCD watches were launched at the west-coast department store chain Troudman’s Emporium. Sales at Sears Roebuck soon followed, with Albatronix, Ness Time, and Nepro also selling Microma digital watches. The Microma watch sold for $250, competitive with fine mechanical and electric watches and far less than other quartz offerings. But the initial models were finicky, especially the display, and return rates were said to be over 25%.

Still, Intel persisted with the development of the Microma line, including the first digital LCD watch for ladies. Another Microma innovation was a continuous display of seconds, but since the display could only show four digits this was achieved by pressing a button and switching the function. This concept would soon be commonplace, with calendar and chronograph functions added to future models.

Image: Europa Star 86, 1974

The initial Microma models used two button cell batteries, but battery technology was improving alongside CMOS and the next-generation Microma used just one. Still, the batteries did not last long and this was one of many issues with the Intel watch. One unusual approach to solve this problem came from Timetron of Hong Kong, which outfitted a Microma model with no less than eight 1.5 volt batteries in parallel!

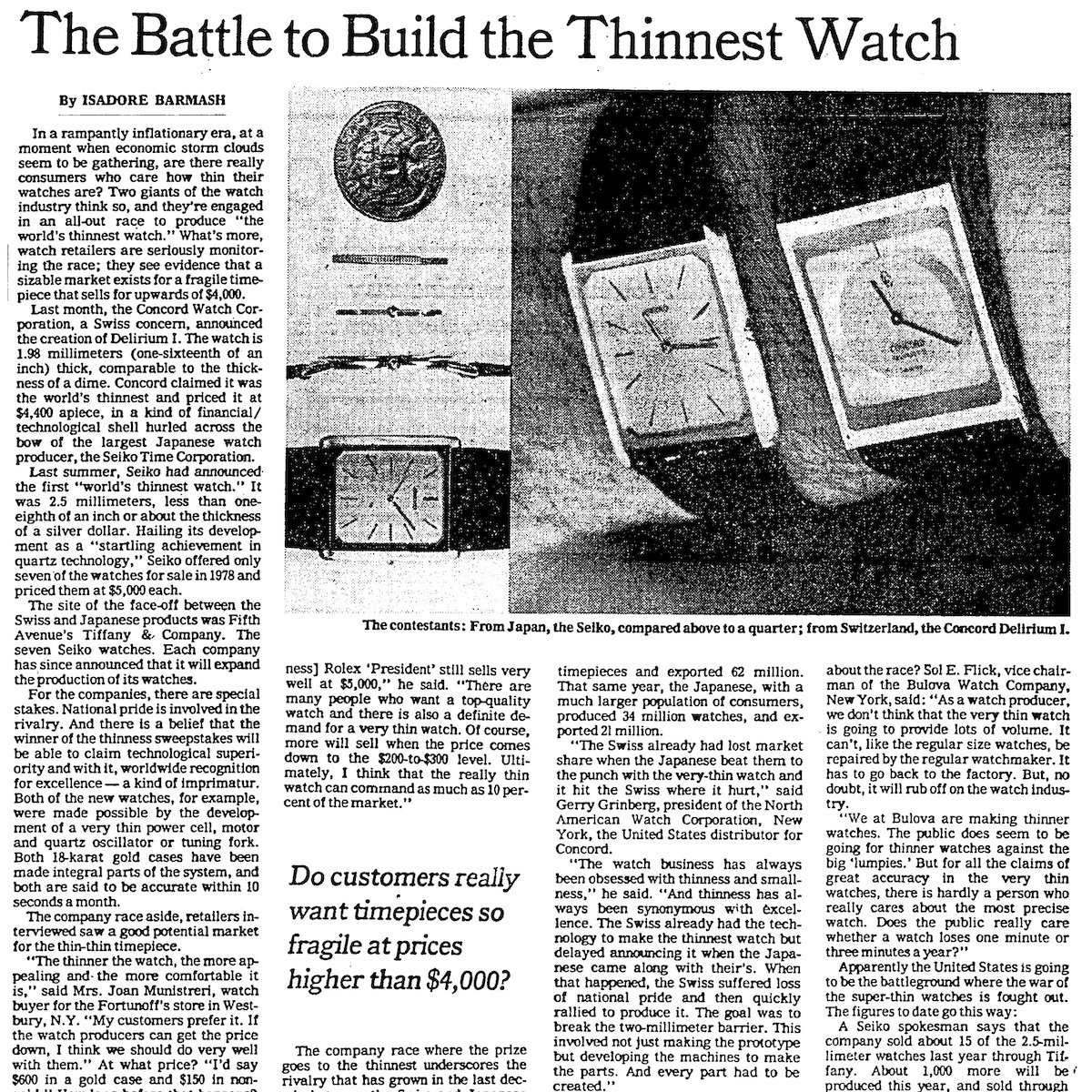

Competition was heating up, however. Optel signed on additional users for their LCD module, including a consortium of German brands as well as the General Time Corporation, maker of Westclox and Seth Thomas. But Field Effect LCDs were far more promising, and both Seiko and Citizen threw their weight behind the Cleveland-made Ilixco display. On the IC side, SSS, AMI, and Sharp were competing with the powerful Texas Instruments.

Intel’s System on a Chip

Intel envisioned a radical concept to bring cost and power down, and to compete with these challengers. Rather than producing components, Intel would build a “system on a chip” that combined every element into a single CMOS chip. All that was needed to build a complete watch was a quartz crystal, a display, a battery, and a few supporting power components. This promised far greater efficiency but also forced customers to standardize on a single supplier for most of the watch. This same concept is still dominant in mobile devices, from the Qualcomm Snapdragon to the Apple M1!

Intel made a major push in the watch market with their next model. The new Microma boasted a two-line display, showing the date continuously and transforming into a chronograph at the press of a button. But Seiko, Citizen, and many other companies were making watches with similar technology and capability and selling them around the same price. Despite a high-profile television ad featuring the actor of “Father Mulcahy” on M*A*S*H failed to energize the buying public.

Image: Europa Star 99, 1976

Image: Intel Corporation

Andy Grove was rapidly rising inside Intel, and he expected results from the Microma division. Dick Boucher, Grove’s choice to lead the division, recalled that it was a “difficult business” and that Intel lacked a plan to tackle the consumer market. Ultimately, Boucher spotted the key issue with Microma (and modern smart watches): “The watch business is not a technology business.” Marketing a consumer product like jewelry is completely different from the chip business and requires different skills and staffing. Ultimately Intel was unable to sell consumer products.

Microma Swiss and ASUAG

Image: Europa Star

In September of 1977, just five years after purchasing Microma, Andy Grove and Gordon Moore raised the white flag. Intel announced it would exit the watch business and put Microma up for sale. The buyer was none other than ASUAG, the Swiss “superholding” company that also controlled brands like Longines, Oris, Mido, and Eterna as well as essential Swiss suppliers like Ebauches SA. Incredibly, ASUAG focused on the Microma consumer brand rather than their SoC and LCD expertise. Microma was specifically acquired by Endura SA, part of the General Watch Co. (home of ASUAG’s watch brands) rather than Ebauches SA or ETA (maker of watch movements).

Now called Microma Swiss, the brand continued for a few more years with good but not exceptional products that shared technology with other ASUAG brands. Key among these was the so-called “hybrid” display, which combined conventional hands with an inset LCD readout for additional complications. This was developed by Ebauches SA in Switzerland and was unrelated to the Intel technology. Microma did continue to offer pure LCD watches based on the Microma SoC, but these quickly fell behind Seiko, Citizen, and Casio, who were rapidly dropping prices on their offerings.

By 1980 the Microma lineup was almost identical to that of other ASUAG companies like Longines, Mido, or Certina. One last gasp was the so-called “Golden Quartz”, a new LCD that could display analog hands or digital numerals on a gold background. The Microma brand was retired around 1986 amid the continuing consolidation in the Swiss industry that saw ASUAG merge with SSIH and launch the revolutionary Swatch.

Images courtesy of Europa Star

The Grail Watch Perspective

Gordon Moore wore his Microma watch for many years after giving up on the brand. He called it “my $15 million watch” and said it served as a reminder to be humble and never again try to enter the consumer market. Notably, Moore wore a later Microma chronograph, not the trouble-plagued first-generation model! A few Microma models are exhibited in the Intel museum and the company’s dalliance in the watch market is documented in their online timeline. But Intel’s experience with Microma, which Gordon Moore himself saw as a major life lesson, was mostly overlooked in remembrances following his death in 2023. Hopefully this article helps set that right.

The most immediate lesson of the Microma story is that technology companies should be wary when entering consumer markets. This is certainly the lesson cited by Dick Boucher, Andy Grove, and Gordon Moore. But the story of Microma might not have had a happy ending even if Intel had focused on being a component supplier for watchmakers. Texas Instruments attacked the space relentlessly, with their own CMOS watch SoC dropping rapidly in price and adopted worldwide. Yet even they were unable to compete with the likes of Seiko and Casio which, like Intel, developed their own integrated consumer products rather than chipsets. Perhaps the true lesson is that consumer products need relentless innovation and focus on customers, with technology being of secondary importance. This is a lesson all companies in the consumer space ought to learn!

References

As I often do, I began documenting my research at Watch Wiki in my new Microma article. One primary source cited there is an NPR story on Gordon Moore and Intel’s “Smartwatch”. More information is available in Intel’s article, “Apple Watch Revealed: The Original” as well as the Intel Timeline. Images of Gordon Moore came from Intel PR. I also recommend Richard S. Tedlow’s book, “Andy Grove: The Live and Times of an American Business Icon.”

On the technical side, I relied on the excellent work of Pieter Doensen on Dynamic Scattering LCD and Field Effect LCD watches. And the Europa Star archive is always an amazing source of information!

Leave a Reply