Imagine being selected to judge a contest of fine watches and finding a counterfeit of your own company’s product! That’s exactly what happened to Adrien Philippe at the Universal Exposition in Antwerp in 1885, and the resulting furor (including government sanctions and a high-profile court case) laid the foundation for anti-counterfeiting measures to this day. Incredibly, the perpetrator of this fake (labeled “Pateck & Cie, Genève”) was a respected watch trader, Armand Schwob, who insisted that it was Patek Philippe that was in the wrong. Let’s take a look at the “Affaire Pateck-Schwob”!

Philippe Discovers the Pateck in Antwerp

On Thursday, July 9, 1885, an international jury of experts slowly made its way through the halls of the Universal Exposition in Antwerp. They examined the display cases in the halls dedicated to France and Germany, but spent most of their time in the Swiss exhibition. Most of the space was dedicated to watchmaking, though there were also displays of music boxes, cigars, shoes, wine, and chocolates.

The reputation of Swiss watches varied greatly by canton at this time: Fine watches from Geneva, modern designs from Bern, watch movements from Vaud, and more “common” offerings from the Jura mountains above Neuchâtel. But the watchmakers of “the mountains” were rapidly improving their craft, and this was evident at the Antwerp exposition, especially since few Geneva watchmakers chose to exhibit that year. As noted in the program, “the watch display offers a complete set, from the simplest watch to the most complicated and perfect chronometer.”

Along with long-forgotten makers like Charles Couleru-Meuri were a few familiar names: Ernest Francillon showed the products of his modern factory (known even then as Longines), Charles Tissot showed a chronograph with moon phase and full calendar, L.-U. Chopard showed his fine workmanship, and Gedeon Thommen displayed his modern watchmaking machinery. The jury took it all in, requesting a closer look at interesting pieces from the eager representatives manning the counters.

One of the most impressive displays in the hall bore the name Armand Schwob & Frère. These Parisian brothers worked with craftsmen throughout the Swiss Jura region, representing their best products through an office in La Chaux-de-Fonds. Unlike many in the city and region, Schwob produced a wide range of watches in many different styles and even bought the products of others for wholesale. The firm boasted that its annual sales reached four million francs, an unbelievably-large amount in the 1880s!

When the jury arrived at Schwob’s display case, they were met by a representative of the factory with a tray of pre-selected watches to examine at a central table. This was highly unusual – the jury typically gathered around the display case and picked the specimens themselves to evaluate. As noted in a contemporary report, “this eagerness seemed to us to include a hidden irregularity; consequently, we asked him not to trouble himself so much, preferring to select items ourselves at random.”

After examining a few valuable pieces, the jury spotted some “inferior and shoddy” watches in the corner. Although they were cased in gold, they used plain movements and were not as well-finished as the rest of the Schwob line. The jurors were dumbfounded on opening the cases to read the inscription: All three were inscribed “Genève”, while one even bore the signature, “Pateck & Cie!”

This was especially galling to the chairman of the jury: Adrien Philippe himself!

Aghast, Philippe and the jury stepped aside to deliberate. After a short discussion, the jury stepped forward and seized the three watches in question, vowing to deliver them to the Swiss Central Committee along with a full report. Then they turned to the Commissioner of the Swiss exhibit, none other than Ernest Francillon of Longines, demanding the removal of the Schwob & Frère display. Despite a concurring complaint from the Société Intercantonale des Industries du Jura, Francillon worried that a scandal would embarrass the Swiss delegation. The issue was kept quiet for the time being.

Initial reports home from Antwerp made no mention of the bogus watches. Indeed, the Armand Schwob & Frère display was praised in the press! Even Adrien Philippe’s own account of the exposition, published in the Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie, made no mention of the controversy.

But the case raised the ire of another party that refused to stay quiet: Councilor of State Dufour broke the news in an open letter to the Swiss papers that the firm had used the word “Genève” improperly and deserved to be investigated. There had been a long-running trend of false “Geneva watches” appearing for international sale, and the manufacturers there pushed for the establishment of hallmarks and special designations for their products. This work was showing progress, and they would not stand by in the face of yet another false “Geneva watch”.

Armand Schwob responded aggressively in the press, declaring that Patek, Philippe & Cie had no right to object to their use of a similar (but differently-spelled) name. He also claimed that it was just a single mis-labeled watch in their display, and that it was not one of their products. Then he went further, attacking Dufour as a disgruntled competitor mis-using the power of the state, and even suggested he was involved in a recent gold-smuggling scandal!

Not content, Patek, Philippe & Cie brought official charges against Armand Schwob & Frère on April 26, 1886. Adrien Philippe felt free to speak out as well: His fourth article, published in June 1886, included a detailed first-hand account of this shocking find.

The Case Against Armand Schwob

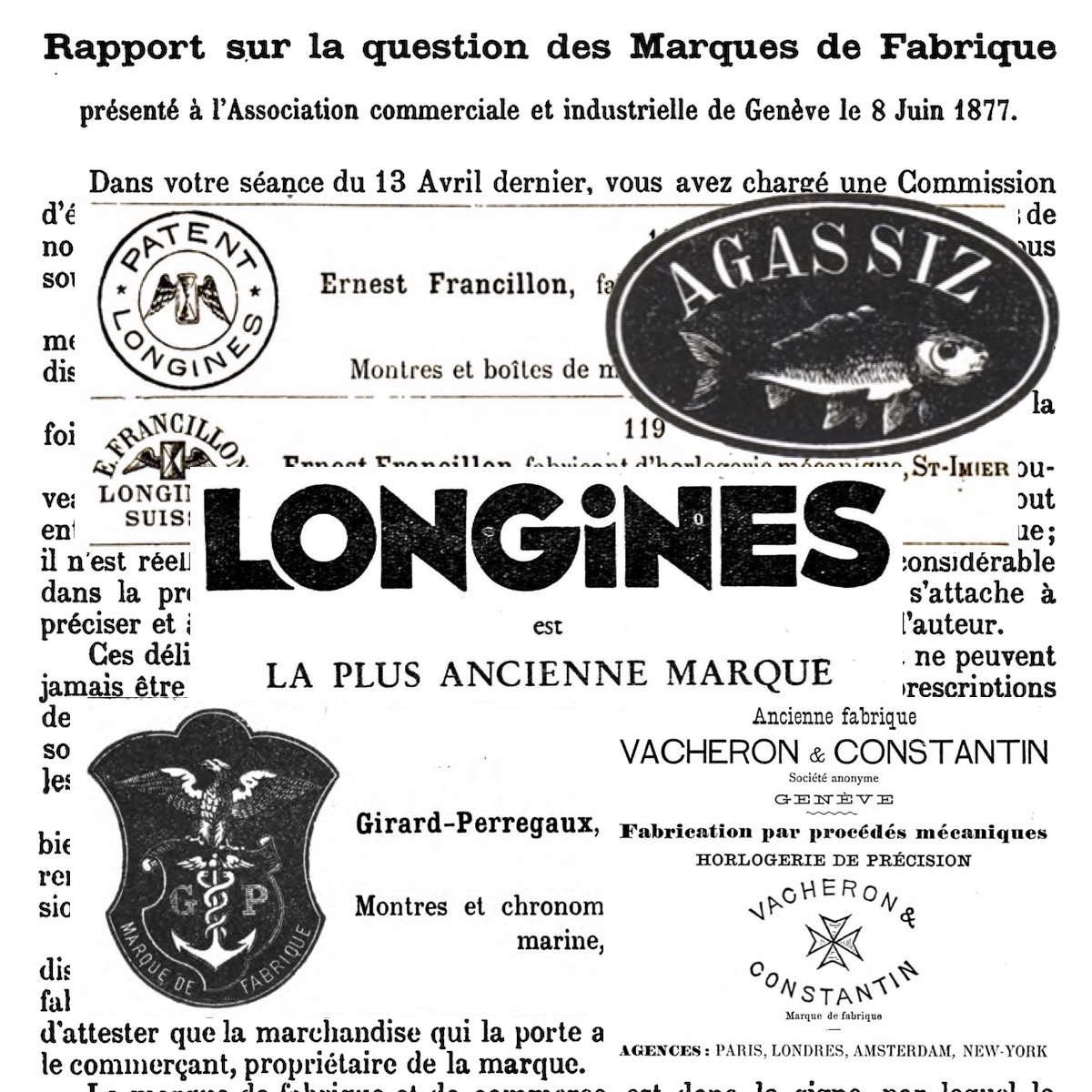

The case against Armand Schwob was the first legal test of brand or trademark protection in Swiss courts. The protection of intellectual property, and indeed the whole concept of a protected brand or trademark, were new concepts in the 1880s. Indeed, the Swiss authorities had only recently enacted a law enabling companies to register fictitious names for companies and products, with the first registrations awarded on November 1, 1880. Armand Schwob was well aware of these protections, registering at least six trademarks before the Antwerp Exposition in 1885.

The court in Neuchâtel focused on the appropriation of brand equity due to the similarity of the name “Pateck” to the famous “Patek, Philippe & Cie.”

Armand Schwob hired former Paris police prefect Léon Renaud to defend the company in court, along with a pair of local lawyers. He made a series of incredible claims:

- That the name “Pateck” could not be confused with “Patek”, given the added letter “c”;

- That it was common practice to label watches with this name;

- That the watches were of such obviously inferior quality that no one would confuse them with the products of the famous Geneva firm

Schwob’s lawyers made two less-frivolous claims as well:

- That the trademark law did not explicitly apply to product branding

- That trade names must be registered to be protected (which was impossible for the names of living people)

By far the most astounding defense argument was that it was Patek, Philippe & Cie that should lose access to the name “Patek”. After all, Antoine Norbert de Patek died in 1877, and Swiss law did not allow for continued use of the names of people no longer associated with a company. Shouldn’t the firm become “Philippe & Cie” and lose not just their use of “Patek” but their claim against Armand Schwob? Given the strength of the rest of the case, the court did not rule on this point. But (as I discuss below) it might have had the greatest impact of any argument in the case.

The arguments and counter-arguments lasted for four days in November of 1890. Despite their previous claims, Schwob & Frère admitted in court that the watches in question were indeed their products. Adrien Philippe supposed that more infringing watches had been brought to Antwerp, and he was proven right: The court determined that the La Chaux-de-Fonds firm had produced or sold at least 678 watches bearing the inscriptions “Pateck” or “Pateck & Cie, Genève” through July, 1885!

On November 18, 1890, the Cantonal Court rendered its verdict: The firm of Armand Schwob & Frère was found guilty. Patek, Philippe & Cie had requested a fine of 50,000 francs, but the court reduced this to 15,000 francs plus legal costs. Although this was a considerable sum at the time, contemporary reporting criticized the leniency of the court given the importance of the case.

Both parties immediately appealed the decision to the Swiss Federal Court.

On February 13, 1891 the high court rejected Armand Schwob’s appeals and affirmed the amount of the fine. The court also added one more punishment rejected by the Neuchâtel judge: Armand Schwob would also pay to publish an announcement of the judgment in two Swiss and two foreign newspapers chosen by Patek, Philippe & Cie.

With the case settled and appeals exhausted, Schwob was forced to pay the fine. Patek, Philippe & Cie donated 1000 francs of this money to the Canton of Neuchâtel to support underprivileged watchmaking apprentices and another 1000 francs to the city of Geneva to support an annual prize for young watchmakers.

Armand Schwob & Frère was not so fortunate. Although the company had sufficient financial reserves to cover court costs and the 15,000 franc fine, the notoriety of the scandal made it difficult to continue to represent Swiss watchmakers. The company filed for bankruptcy on May 6, 1892. The firm’s creditors forced a sale of the company’s assets in October of that year, including gold, silver, and base metal watches and un-cased watch movements.

Who Was Armand Schwob?

Armand and Abraham Schwob were born in Hégenheim, just outside the walls of Basel. This was a thriving Jewish town, since anti-semitic laws excluded them from Basel. Despite prejudice and restrictions, a synagogue and cemetery were built there, and many of the Jewish residents became successful in the businesses in which they were later pursued by the Schwob brothers: Trading in watches, leather goods, and finance. But The Schwob children might have witnessed the anti-Jewish riot of April 23, 1848 and could have known the child killed by the mob that day.

Many Alsatian Jews immigrated to Switzerland in the second half of the 19th century. This included Joseph Schwob-Weil and Isaac Schwob, both of whom financed Henri Sandoz’ Tavannes Watch factory. These families came together in 1919 under the name Schwob Frères and found great success with the Cyma watch brand and civic life in La Chaux-de-Fonds. Despite sharing a common name, these Schwob families were not directly related to each other or to Armand and Abraham Schwob. Incredibly, all three worked out of the same buildings on Rue Léopold-Robert in the 1880s!

The firm of Armand Schwob & Frère was first listed in the Jura directory, Indicateur Davoine, in 1880. The company was located at Rue Léopold-Robert 14 from 1880 through 1893, the entire span of its existence in the city. This is a large office building in the center of La Chaux-de-Fonds, overlooking the Grande Fontaine at the head of the avenue. Many other watchmakers were also located in this space, which was replaced in the 20th century by a modern glass and concrete building.

The December, 1882 edition of the French Journal de l’Horlogerie Française shows both Armand and Abraham Schwob as members of the Chambre Syndicale de l’Horlogerie de Paris, with their office at Boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle 19. Despite being just outside the walls of Basel, Hégenheim is located in France and the Schwob brothers were likely French citizens. It appears that they lived in Paris throughout their professional lives.

Despite the wording of their advertisements, Armand and his brother Abraham never operated a watch factory or even much of a workshop. They were traders, buying watches from the craftsmen of the Swiss Jura and selling them abroad, especially in France. The region was just emerging as a center for high-quality watchmaking, and Armand Schwob associated himself with the best workshops and artisans. And his home in Paris gave him access to a ready and well-heeled clientele!

The firm of Armand Schwob & Frère dealt with a wide range of watches, including some of the best produced in the region. One watch in particular is worth noting: In 1883 the firm took first place in chronometer testing at the Neuchâtel Observatory. The watch in question used a tourbillon escapement built by noted Le Locle watchmaker Albert Pellaton-Favre, the master of tourbillons in the 19th century. The esteemed director of the Observatory Adolphe Hirsch called Pellaton an “excellent artist” and personally praised his work on this watch.

The company followed this with an appearance at the 1883 Universal Exposition in Amsterdam. A correspondent for Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie praised the display case of Armand Schwob & Frère as being “among the richest in terms of furnishings.” This was perhaps the same display used at the Antwerp expo the following year. And as mentioned above, the company boasted of annual turnover of 4 million francs.

Incredibly, the scandal and judgments did not mean an end to the careers of Armand and Abraham Schwob. Secure in France, the brothers registered a leather-trading company in Geneva in 1889. They also continued to look for new watches to market, and soon found something really special!

In 1888, a representative for the Schwob brothers named Hughes Rime patented a new novelty: The Mystery Watch! This pocket watch was entirely transparent, with the hour and minute hands mounted on glass discs driven by a concealed movement. The model caused a stir at the 1889 Paris Exposition, with the prototype stolen from the display case! The “montre mystérieuse” was retailed by none other than Armand Schwob & Frère of Paris, and they reveled in this second shot at fame. Schwob was even made an Officer of the Order of the Lion by the Shah of Persia, who very much enjoyed the novelty watch.

Read this excellent article by Juan F. Déniz for the Antiquarian Horological Society, “The First Transparent Watch“

Although I could not find records of the later life and death of Armand and Abraham Schwob, it is likely that they continued to enjoy success in Paris long after the Pateck scandal.

Reacting to the Pateck-Schwob Scandal

Now you can see why the Pateck-Schwob scandal is so incredible. Why would an established and respectable Franco-Swiss watch trading firm deal in bogus Patek Philippe watches, especially poorly-made ones? If it had only been one or two, I might have assumed they were using them as a negative baseline for comparison during customer demonstrations. But there were hundreds of these “Pateck” watches made, at a time before mass production. This would have been a significant part of their product lineup!

Amazingly, these watches continue to turn up for sale. Pictured below is a “Pateck & Cie, Genève” pocket watch sold by Henry’s Auktionshaus in 2015. Many similar watches have been put forth in web forums and auctions over the last decade, and many more have changed in the previous century. It is clear that collectors and dealers are puzzled by these “Patecks” yet consider them to be at least moderately valuable.

In April of 1920, the Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie saw fit to warn readers once again of the risks of bogus watches. The article, translated below, discusses the case as well as two instances where these watches were still in circulation. The writer recounts finding “Pateck” watches proudly displayed in the windows of watch dealers, and the incredulity of those dealers when he pointed out that these were counterfeits. These stories sound remarkably timely in this era of franked-watches and dubious auctions!

The Case Against Patek…

Have you ever heard the stories of famous Swiss watch companies hiring “do-nothing” employees based on their family names? It is often said that the companies were forced to do this due to a quirk of Swiss trademark law: They could not continue using their historic names without someone of that name on staff! I have heard this story leveled at Patek Philippe in particular, and always wondered if there was any seed of truth in it.

Perhaps the Pateck-Schwob affair gives us a clue!

Today, Swiss law allows companies to register and enforce their historic names and brands, but the original law of 1879 was restricted to fictitious names. Companies were forced to change their names following the death or exit of the founder, and thus lost access to those erstwhile eponymous brands.

With so many watch companies being named after their founding father or family, this caused issues when industry consolidation came. Witness the change of the Blancpain company to Rayville, for example. At the same time, many historic family names were traded for brands through the 20th century: Francillon became Longines, Favre-Jacot became Zenith, Perret et Berthoud became Universal Genève, and so on. Even those that kept their historic family association switched from the name of a person to a more-generic brand when they were incorporated: Jaeger-LeCoultre, Vacheron Constantin, and even Patek Philippe!

Armand Schwob’s accusation that Patek, Philippe & Cie should cease the rights to the name “Patek” following the death of Antoine Norbert de Patek in 1877 might sound ridiculous today, but the Federal Court actually found this argument to be credible! Perhaps Adrien Philippe rushed out to hire someone by the name of Patek just to be sure, and this practice became a practical back-stop against other such claims in the future!

It is important to remember that this was the first test of trademark law in Swiss courts. Everything that happened, from the arguments to the verdict, became precedent. It is quite likely that the legacy of this scandal is far deeper than one would assume!

References

As always, I personally researched this story from historic sources without any attention given to current industry folklore. I stumbled upon this story while researching the Schwob family behind the Cyma brand, and specifically attempting to identify the Armand Schwob who was part of the management of Cyma and Tavannes in the 20th century. He is unrelated to the Pateck-Schwob affair, but as often happens this research opened a new door.

Once again, there are far too many references for me to include in this article. A few key primary sources are worth including, however. Also, I do recommend reading the excellent article by Juan F. Déniz for the Antiquarian Horological Society, “The First Transparent Watch“.

All of the dates and facts in this article were personally researched in my historical archive. I drew in particular on the Indicateur Davoine, Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie, and La Fédération Horlogère, all of which are available at The Watch Library. Much more research was conducted in the Swiss National Library online newspaper archives as well as the ETH Zürich E-Periodica database.

The Pateck-Schwob Trial

On July 9, 1885, the house of Patek-Philippe & Co., based in Geneva, discovered at the Swiss section of the Antwerp Exhibition, in the display cases of A. Schwob & Brother of La Chaux-de-Fonds, watches bearing the name “Pateck, Geneva.” This caused a stir among the jury, leading to discussions, correspondence, and an official report recommending the removal of A. Schwob & Brother’s display.

Mr. Francillon, the Swiss commissioner for the exhibition, received a copy of this report along with a similar complaint from the Intercantonal Society of Jura Industries. However, the matter did not proceed further during the exhibition itself, as Mr. Francillon sought to avoid a scandal within the Swiss section.

The Schwob house brought the incident to the public’s attention through the press, claiming good faith while admitting that one watch marked “Pateck & Co.”—not of their manufacture—had been found in their display. Schwob complained of being insulted and defamed by competitors.

Patek-Philippe & Co. argued that Schwob’s actions caused significant harm by misusing their name or parts of it to inscribe inferior quality watches, which were then sold as Patek watches. They identified three main damages:

- Loss of revenue from the sale of counterfeit Patek watches.

- Harm to the reputation of genuine Patek products, as experts declared Schwob’s watches to be vastly inferior.

- Damage from the sale of low-quality gold watches bearing the counterfeit mark.

A. Schwob & Brother claimed that inscribing “Pateck & Co.” on watches that could not be compared to those of Patek-Philippe could not deceive buyers or steal customers. They argued that the longstanding practice of engraving “Pateck” on watch cases had always been known to Patek-Philippe, who had never protested until now. Schwob maintained that genuine Patek watches were distinct from common “Patek” watches (often spelled without a “c”) and asserted their good faith, claiming no harm was caused.

Trial and Judgment

Representing Patek-Philippe & Co. was Mr. Monnier, a lawyer from Neuchâtel. A. Schwob & Brother were defended by Mr. Léon Renaud, a former Paris police prefect and prominent French barrister, alongside lawyers Jeanneret and Breitmayer from La Chaux-de-Fonds. The trial lasted four days, and after two and a half hours of deliberation, the cantonal court ruled:

- Prohibition: A. Schwob & Brother are forbidden to use the name “Pateck.”

- Damages: A fine of 15,000 francs must be paid to Patek-Philippe & Co.

- Non-publication: The judgment will not be published in newspapers.

- Costs: A. Schwob & Brother must bear all court costs.

The court found that A. Schwob & Brother had violated trademark laws. The ruling clarified a key legal point: registration of a trade name as a trademark is unnecessary; simply inscribing a trade name, duly registered in the commercial register, on merchandise constitutes a trademark.

In concluding the judgment, the court president emphasized that this trial addressed a deeply problematic custom long entrenched in the watchmaking industry. The judgment is expected to set a significant precedent, deterring other watchmakers from exploiting reputable names or counterfeit versions of them to market inferior products. This ruling ensures that those who have built their reputation through the excellence of their products retain the exclusive benefits of their efforts and sacrifices—a matter of justice and morality.

INDUSTRIAL PROPERTY

Regarding a Trademark

At the 1885 Universal Exhibition in Antwerp, the watchmaking jury was presided over by the late Adrien Philippe, who contributed a series of articles to our journal on this occasion. These articles, as interesting as they were humorous, appeared in our 10th year. We extract the following passage, relating to a “very powerful house, it seems, which modestly announces a turnover of four million francs.”

- We believe it is useful to clarify the exact name of this company, which was Armand Schwob et Frère, and not Schwob Frères as Philippe had written. — Ed.

“After examining some pieces of considerable commercial value, we stumbled upon the most inferior, shoddy watchmaking of the entire exhibition. These pieces, utterly beyond criticism, bore inscriptions on the case: one read Patek & Co., and two others simply had the name Geneva in large letters. We jurors looked at each other in astonishment! How could anyone dare, at such a solemn exhibition, to present merchandise under the guise of false names? We were stunned!

“We immediately deliberated and decided to seize these three watches and draft a report to the Swiss central committee, detailing the facts and requesting the removal of the display case, which was done immediately.”

The case caused a significant stir at the time and led to a lawsuit, which we reported on in detail (XV, 166 and 279). The proceedings concluded with a ruling that ordered the firm Patek, Philippe & Co. to receive damages of 15,000 francs and allowed the publication of an extract of the ruling in two Swiss and two foreign newspapers.

That was 35 years ago, yet it seems necessary to remind certain manufacturers of these events and their consequences. Evidence of this necessity comes from the following article, published in the Deutsche Uhrmacher-Zeitung on February 12 and signed by Mr. Loske:

COUNTERFEIT PATEK WATCHES

A Warning

Thirty years ago, a case that caused some sensation was decided before a Swiss court. A watch manufacturer had flooded the market with gold watches bearing the inscription “Pateck, Geneva” on the dial and especially on the case back. The case was not straightforward, as the founder of the current joint-stock company Patek, Philippe & Co. spelled his name without the “c.” One particularly prejudiced lawyer even argued that the company had no right to adopt the name Patek or Pateck without additional qualifications, while simultaneously claiming this right for the defendant firm he represented.

However, the court’s decision was clear: the company that had used the name Pateck to deceive the public was fined 15,000 francs and ceased its dishonest practices thereafter.

Why do I recount this story? For a very valid reason related to public morality, the decline of which is so often and justly lamented. Some time ago, I visited a watch shop with an acquaintance who wished to view gold watches. Among the first presented was one of these “Pateck” watches—with the “ck”—that appeared “polished up” and dated back at least 30 years. Internally, the watch’s condition was even worse.

When I remarked to the clerk in the absence of the owner, “You don’t mean to claim this is a genuine Patek watch, do you?” he replied, “Of course, it’s a Patek, Philippe & Co.” By doing so, perhaps in good faith, he placed himself in a precarious legal position, as he implied he was familiar with genuine Patek watches.

When I asked, “Where is the Patek, Philippe & Co. name? I only see Pateck, Geneva, and the name is even misspelled!” he examined the case back carefully and responded, “But it’s still a Geneva watch.” This statement is meaningless, as Geneva has long produced movements of all kinds, and in this case, it was also false—the condemned company referenced earlier was based in Neuchâtel (La Chaux-de-Fonds).

A Second Case

Even worse is a second case. In a prominent display window on Leipzigerstrasse in Berlin, one can see one of these counterfeit Patek watches exhibited. The movement, presented under this false guise, is of mediocre quality at best. Next to the watch is a small card reading:

Genuine Pateck watch, Geneva.

The best manufacturing in the world.

Case, lid, and back in fine gold.

It raises the question of whether the store owner realizes the risk he faces by selling this watch under these three false claims. Even if he is not a watchmaker, as an experienced merchant selling watches, he must know that this is not of “the best manufacturing,” but rather an ordinary product. He surely knows that the case is not “fine gold,” but merely 14 karat gold, which is evident even from the street. He must also know that fine gold cases do not and cannot exist for practical use.

To which unsuspecting customer will this counterfeit Patek “in fine gold,” as advertised, eventually be sold? Whoever it is, they will likely be bitterly disappointed, as the performance of this old movement, at least 30 years old, will not meet expectations of a genuine Patek watch. It is also quite possible—at least I hope so—that they will encounter a watchmaker who will candidly reveal the truth, leading to a counterfeiting lawsuit that could tarnish the reputation of the entire trade.

Concluding Remarks

Complaints about the degeneration of public morality are certainly justified. An individual alone may not be able to combat this sign of the times, but all who have the opportunity must speak out firmly against such abuses instead of turning a blind eye out of misguided professional solidarity. Wrongdoers must be publicly exposed. These wrongdoers are not just those who harm the watchmaker’s wallet but also those who shamelessly ruin the reputation of honest and conscientious merchants.

Leave a Reply