Automatic watches were hot in the 1950s, and chronographs were cool in the 1960s. But bringing these technologies together was not at all straightforward! Three different automatic chronograph movements were launched in 1969, and the story of their creation reflects the turmoil of the industry at that critical time. As was the case with quartz watches, it’s hard to say who came first in the race to produce an automatic chronograph. But there is also some important context needed to understand this story: The development of chronographs and automatic movements, the evolution of Heuer, Breitling, Dubois Dépraz, Zenith, and Seiko, and the reason the automatic chronograph was needed in that time and place.

Note: Jeff Stein told this story very well at On the Dash, and I suggest you read his series for International Watch Magazine, “Project 99 — The Race to Develop the World’s First Automatic Chronograph.” I’ll try to provide some context to go along with the story here!

Chronographes and Compteurs de Sport

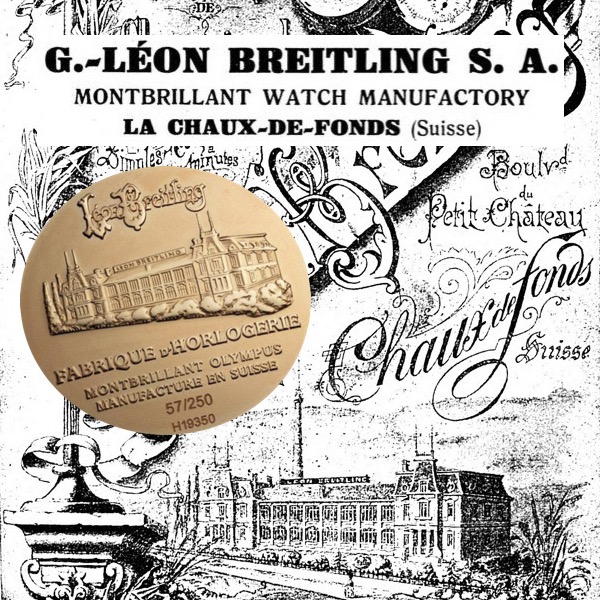

The story of the automatic chronograph must begin with two rival watchmakers. Both Edouard Heuer and Léon Breitling came from Saint-Imier, but Heuer was 20 years older. He established his business there in 1860, the same year Léon Breitling was born. Heuer relocated to Bienne in 1867 and began series production of chronographs in 1882. The young Breitling headed to La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1892 to set up his workshop. Both Heuer and Breitling were successful in the stopwatch (“compteurs de sport”) and chronograph pocket watch market, and the firms had become fierce rivals by 1900.

Many other firms also competed to supply chronographs (watches with a timing mechanism) and stopwatches (timing-only devices) at that time, but Heuer was in the lead after World War I. They supplied stopwatches to the Olympics for decades starting in 1920, and these were widely seen at sporting events of all sorts. Heuer is also recognized for producing the first wrist-mounted chronograph watch, and “bracelet-montres” were just starting to be in demand among sporting and military men.

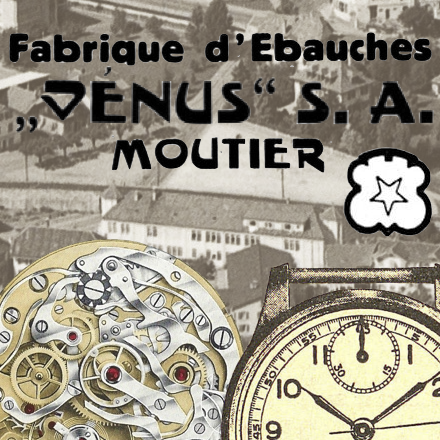

The market for complicated pocket watches, including chronographs, attracted new competitors at this time. Dozens of companies began producing chronograph movements, including Excelsior Park, Lemania, Leonidas, Le Phare, Minerva, Nicolet, Omega, Reymond Frères (which became Valjoux), Universal, and Venus. Although it was a smaller segment of the overall market, chronographs and timers were in demand and could be sold for a profit.

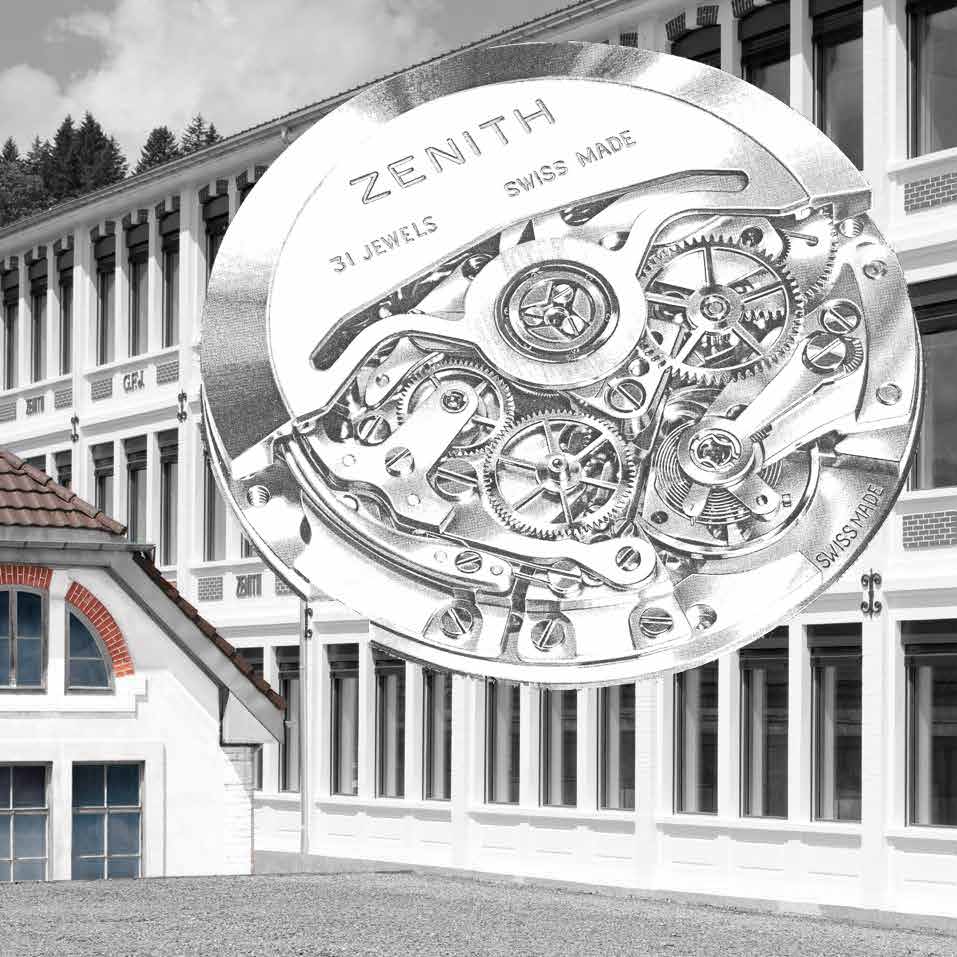

In Le Locle, watchmaker Georges Pellaton-Steudler set up a factory in Les Ponts-de-Martel to produce complicated movements, including chronographs under license from Universal. He soon attracted a contract from Zenith, and the Martel Watch Company became an important producer of chronographs. Martel would be closely associated with Universal and Zenith for decades, even after the former relocated to Geneva and the latter adopted movements from Saint-Imier rival Excelsior Park.

Initially, Martel produced pocket watch movements based on Universal’s designs. But the watchmakers in Ponts-de-Martel were complication experts, and they were tasked by Universal to develop smaller and more modern movements. The patents on such well-known movements as the Universal Cal. 281 prove that it was designed by Martel, and these were produced in the modern facility there as well. Because Martel applied “Universal Genève” or “Zenith” to the bridges, the company is rarely recognized for their design and production expertise.

Martel assembled complete chronograph watches for both Universal and Zenith, and there is much branding confusion because of this. In the 1940s, both companies used the “Compur” and “Compax” names for Martel chronograph watches, and Zenith even produced a model called the “Universal”! Martel also produced Movado chronographs, another name we shall see in this story.

Further to the West, in the Vallée de Joux village of Le Lieu, watchmaker Marcel Dépraz also contributed to the development of chronograph watches. Marcel and his son Roger Dépraz specialized in the creation of complications based on ebauche movements from others, notably Charles Hahn of Le Landeron. But Dépraz also supplied expertise, enabling firms like Hanhart and Tutima to produce chronographs in Germany. His son in law, Reynold Dubois, continued to develop chronograph movements and mechanisms, and came up with a novel concept: A reusable chronograph mechanism that could be mated to various base watch movements. Dubois was also an early innovator in so-called cam-switched chronograph mechanisms which were thinner and cheaper than the complex column wheel designs used previously.

Image: Europa Star Eastern Jeweller 15, 1953

After World War II, a wide variety of mature chronograph watches were available. These were used by scientists and engineers, in sports from skiing to motor racing, and in the military. And the rugged image of these “tool watches” would become primary to the marketing of watches from the 1960s to today. But in the 1940s, the chronograph was still very much a niche product.

Watches that Wind Themselves

The dream of a self-winding watch began in the 18th century, but it was not until the 1920s that John Harwood and Blancpain were able to produce an automatic wristwatch. Harwood used a “see saw” weight with bumpers, as did many others later, but this created a disagreeable feel to early automatic watches. Rolex is responsible for popularizing the concept of a freely-rotating central weight segment, and their “Perpetual” watches became dominant during World War II and beyond. Felsa and Eterna were also early proponents of automatic winding, and soon most other companies were hard at work developing their own technology.

In the 1950s, another major industry trend was the development of ultra-thin and compact watches. But this demand was at odds with the new automatic winding technology, which tended to make watches thicker and wider due to the space needed for the winding rotor. Complications like date windows were also in demand, even though these also tended to add thickness to watch movements.

Universal and Büren worked independently to develop a new winding technology that would allow them to deliver a slim automatic watch movement. Now generically known as “micro-rotor” winding, the Büren “Super Slender” and Universal “Microtor” were announced at the same time in 1958. Neither was particularly slim at 4.15 mm and 4.20 mm thick, respectively, but the technology held promise for slimmer automatic movements. Piaget’s 1959 Cal. 12P was the first ultra-thin micro-rotor movement, measuring just 2.3 mm.

Büren, Universal, and Piaget continued to develop slimmer automatic moments throughout the 1960s. The 1962 Büren Intramatic used a next-generation movement, Cal. 1281, which was just 3.25 mm thick despite including a date mechanism. Büren was also successful in enforcing their patent on the micro-rotor concept, forcing Universal to pay royalties and driving their focus away from the “Microtor” movement.

The micro-rotor was an example of another trend in watch movement design that would help make the automatic chronograph possible: Integration. Rather than stack elements vertically and increase thickness, these designs moved components to the side so the weight segment and winding mechanism could be sunk into the movement. This was the concept embraced by Heinrich Stamm at Eterna, and his central-rotor Cal. 1466U was just 3.6 mm thick. Stamm also tapered the weight segment and provided clearance so it could run around rather than above the movement. Stamm’s Eterna-Matic would be the basis for today’s ETA Cal. 2892A2, and his architecture would be adopted across the industry.

The Question of an Automatic Chronograph

No doubt many watchmakers had considered the possibility of building an automatic chronograph movement, but none succeeded until the end of the 1960s. The reason is complexity: A chronograph mechanism requires pinions through the dial to drive counting hands, levers, wheels, and columns inside, and pushers on the side to actuate the mechanism. All of these components would get in the way of a winding rotor, not to mention the wheels of the winding mechanism itself.

Although the market for chronograph watches was still quite small in the 1950s, these complicated watches were the a profitable and growing segment. These “tool watches” had drawn the attention of industry leaders like Omega and Rolex, and they were leveraging sponsorship of sporting events to grow their sales. This posed a threat to Breitling, Heuer, Leonidas, and so on but it also presented an opportunity. While Universal and Zenith business themselves with automatic movements, perhaps they could leap forward with an automatic chronograph!

If anyone could envision such a design it was Gérald Dubois, the grandson of Marcel Dépraz and a talented designer of chronograph mechanisms. Dépraz & Cie. pioneered the idea of a universal chronograph mechanism that could be positioned under the dial and attached to any watch movement with a central seconds hand. Certainly the company’s engineers would be excited by the prospect of their chronograph paired with an ultra-thin automatic movement like Büren’s Super Slender!

The Martel Watch Company was also investigating the idea of an automatic chronograph. Martel’s partnership with Universal and Zenith had resulted in the first chronograph movement with a date complication and the first with a full calendar and moon phase. These too required careful routing to pinions and placement of gears and proved Martel’s leadership in chronograph design. And Martel was developing their own automatic winding system in the late 1950s, embracing the integrated winding works and tapered central rotor concept. An automatic chronograph movement that combined these was inevitable.

In 1960, Zenith was struggling to maintain its market position and had not yet delivered a fully-developed automatic movement. The greatest threat was Omega, which had taken the lead in the chronograph market. New Zenith boss Leonard Butscher was brought in to right the ship, and he saw the automatic chronograph as an opportunity. Zenith would acquire Martel between 1958 and 1962 to ensure access to their complicated movement technology. And in 1962, Butscher officially directed Martel to develop an integrated automatic chronograph to be released in 1965, the company’s centenary.

About that same time, Gérald Dubois and new Heuer boss Jack W. Heuer were discussing the prospect of developing their own automatic chronograph. Dubois suggested using a slim movement like the Büren Cal. 1280 with a module of his own design, and Heuer agreed. Fearing the cost of such a project, Heuer approached his friend Willy Breitling to combine their resources. The project would give them a major advantage over Omega. An agreement was quickly reached, and a top-secret development effort known as “Project 99” was begun.

Development Hell: The Automatic Chronograph

Heuer and Breitling were right to be worried. Development of an automatic chronograph movement would prove incredibly challenging, especially as watchmaking evolved into a modern industry and technology advanced. The threat of well-funded competitors like Omega, as well as the prospect of electronic and quartz watches, loomed large throughout the 1960s.

Zenith’s project was especially ambitious: Their automatic chronograph movement would be an entirely new design. But the automatic winding mechanism was perhaps more of a concern. Although Martel had a great deal of experience in chronographs, it was a small company and was just developing its first automatic. Plus, Zenith had also tasked Martel to develop a high-volume time-only automatic movement. Resources were stretched to the limit.

To make matters worse, Zenith management wanted to launch these new products in 1965 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the company’s founding. Needless to say, Martel missed this deadline.

On the other hand, although it was now well-funded, “Project 99” required the cooperation of even more companies than originally anticipated. Nearly every member of the group would merge or be acquired during development: Jack W. Heuer had only recently taken over Heuer, and he quickly moved to merge with rival Leonidas in 1964. Hamilton Watch Company, an American firm, purchased Büren in 1966 so they could move production to Switzerland. And Gérald Dubois and Eric Dépraz were taking the reins at their fathers’ company and would reorganize it as Dubois Dépraz SA in 1968.

Zenith faced business challenges of its own. The American Zenith Radio Corp. was increasingly aggressive in enforcing their trademark on the name in the critical United States market. Zenith responded by merging with Movado in 1969, partly so it would be able to market its next-generation products there using this valuable brand. And Zenith management had focused development resources on higher-volume automatic movements instead of their new chronograph.

Then there were the technical issues. The industry was rapidly moving to “high beat” movements in the 1960s. Modern movements were beginning to operate at 28,800 A/h in the 1960s, and Girard Perregaux introduced a 36,000 A/h movement in 1966. Such movements had proven themselves in chronometer competitions and were seen as a way to fend off interest in tuning fork electronic and quartz watches. Zenith management decided that their automatic chronograph would operate at 36,000 A/h, requiring even more materials and manufacturing development time.

Project 99 was also facing technical challenges. The modular approach should have made development easier, since the base movement was a proven production unit. But the Dubois Dépraz module was mounted on top of the movement rather than between the movement and dial as is more common today. This required routing three long pinions straight through the Büren movement to drive the chronograph hands. One passes through the center of the micro-rotor itself, while another sits close to the keyless works. So the base movement had to be modified to make room, giving Büren’s Hans Kocher more work than anticipated.

Gérald Dubois had experience with the basic technologies used by the chronograph module, but a great deal of work was required to bring them together. It relied on cams and springs rather than a traditional column wheel, and this posed challenges in terms of reliability and construction. It connected to the base using an oscillating pinion (as invented by Edouard Heuer himself back in 1887) as on previous Dépraz chronographs, but it had to be reengineered due to its placement on top of the movement. This “flip” also moved the chronograph pushers to the opposite side of the movement from the crown, giving Chronomatic watches a rather distinctive appearance.

Still, both Zenith and “Project 99” were on track for production by the end of the decade. Unaware of the competition, both groups planned for an introduction at the 1969 Basel Fair.

The First Automatic Chronograph?

Sometime late in 1968, Zenith management learned that the Heuer/Breitling consortium planned to launch an automatic chronograph at Basel. Eager to claim bragging rights for the first automatic chronograph, Zenith hastily arranged a press conference to launch first. On January 10, 1969, Zenith unveiled their integrated high-beat automatic chronograph, dubbed “El Primero.” But it was a small affair and drew very little attention. Plus, Zenith were not yet ready to begin production, with perhaps less than five prototype watches created in time for the launch.

By all accounts, Jack W. Heuer and Willy Breitling were surprised and annoyed by Zenith’s announcement, as well as the cheeky name chosen by Leonard Butscher. But they decided to go ahead with their launch as planned, since the Chronomatic was nearly ready for production. On March 3, 1969, Breitling, Heuer, and Hamilton-Büren held press conferences around the world announcing the self-winding chronograph. These caused a media sensation, and the group emphasized that their watch was soon to enter mass production. They even gave away samples to lucky attendees and offered review units to the press.

Image: Europa Star 56, 1969

The Breitling, Heuer, and Hamilton watches were a hit at the Basel Fair as well, with Zenith earning much less notice. One reason was the brash styling and large bold cases developed by Breitling, Heuer, and Hamilton. These helped disguise the chunky Cal. 11 movement, which was 7.7 mm thick. But they also set a new standard for sports watches, and remain icons to this day. It is hard to overlook a Heuer Monaco on the wrist today, and it would have seemed positively radical in 1969. Zenith’s initial El Primero watches had much more conventional styling to go with their slimmer profile.

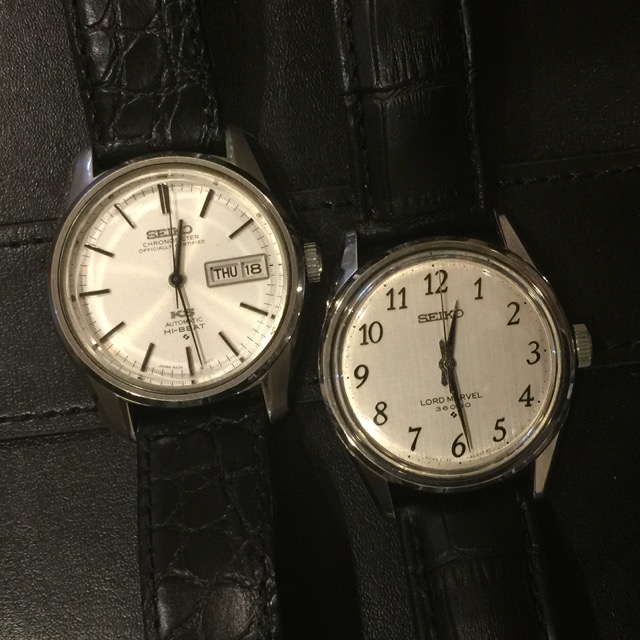

Among those applauding the new watches was Mr. Hattori of Seiko. Jack Heuer remembers Hattori coming to the Heuer booth at the Basel Fair to congratulate the company on their accomplishment. Only later did Heuer and the rest of the industry notice that Seiko had quietly delivered an automatic chronograph of their own in 1969!

The Seiko Speed Timer line was created for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, and Seiko added an automatic chronograph with a 30 minute totalizer in 1969. Ref. 6139 was in production by March 1969 and was widely available for purchase that year. It is pictured in the early-1969 Seiko catalog and featured in many period brochures. Today, most historians recognize Seiko for producing the first automatic chronograph watch available for sale, just as they did a year later when their Quartz Astron watch beat all Swiss rivals to market.

Breitling, Heuer, and Hamilton were also able to deliver the first production Chronomatic watches soon after the announcement. Contemporary advertisements and reports suggest that they were available in stores during the summer of 1969, and there are many examples from that time period today. Although their announcement was scooped, the Chronomatic group deserves credit for quickly bringing their design to production.

Zenith was certainly last to deliver El Primero watches to consumers. Some reports suggest that the company was able to enter production in October of 1969, but this was certainly after Seiko and the Chronomatic. The costly and complicated high-beat El Primero would tax Zenith’s resources, but it remained viable longer than either competing movement. As discussed previously, Zenith’s El Primero was a key piece of the mechanical watch revolution in the 1980s and refreshed versions of that movement remain in production to this day. Despite overruns in development and production, El Primero was announced first and is one of the most important watch movements of all time.

The Grail Watch Perspective: Innovation is a Process

Although it is enjoyable to argue who was first to create an automatic chronograph (or a quartz watch), the realty is that innovation comes from previous developments not spontaneous inspiration. The automatic chronograph could not exist if companies like Martel and Dubois Dépraz had not mastered the creation of chronograph mechanisms, if Büren and Eterna had not paved the way with automatic winding, and if the industry had not embraced integration and modularity. The fact that Seiko developed their own automatic chronograph without even recognizing their own accomplishment shows that innovation is a process and technological development tends to follow the same trajectory for every participant. El Primero, Project 99, and the Speed Timer all deserve credit for moving the state of the art forward in 1969.

References

- Project 99 — The Race to Develop the World’s First Automatic Chronograph, Jeffrey M. Stein, On the Dash

- 1969: The year that changed watchmaking forever, Chris Hall, QP Magazine, 2019

- 50th Anniversary of the first automatic chronograph – Seiko’s 6139, Anthony Kable, Plus 9 Time

- The Fall and Rise of Zenith, 1969-1988, Grail Watch

GREAT HISTORY, OF HOROLOGY.