Industrialization of watchmaking came to Switzerland in the late 19th century and is embodied by the huge Longines factory on the Suze river in Saint-Imier. But steam power came first, enabling the construction of factories across Europe and the United States, including Usine du Parc, home and namesake of Excelsior Park. This is the story of the rise and fall of steam power in Saint-Imier and the exceptional stopwatches made there. It is also the story of the end of steam and of the Excelsior Park factory, and the reasons for its failure.

Usine du Parc was not the largest or newest factory in Saint-Imier. Indeed, the factory building is mostly forgotten today. But “Le Parc” was certainly one of the most important watchmaking concerns ever to come from the small town. The complex, which dated to the mid-19th century, was centered on steam power, and this was what attracted Albert Jeanneret and his brothers to establish their watchmaking company there around 1889. The company would eventually take on the brand name Excelsior Park, and was one of the most recognizable and important manufacturers of chronograph movements in the 20th century.

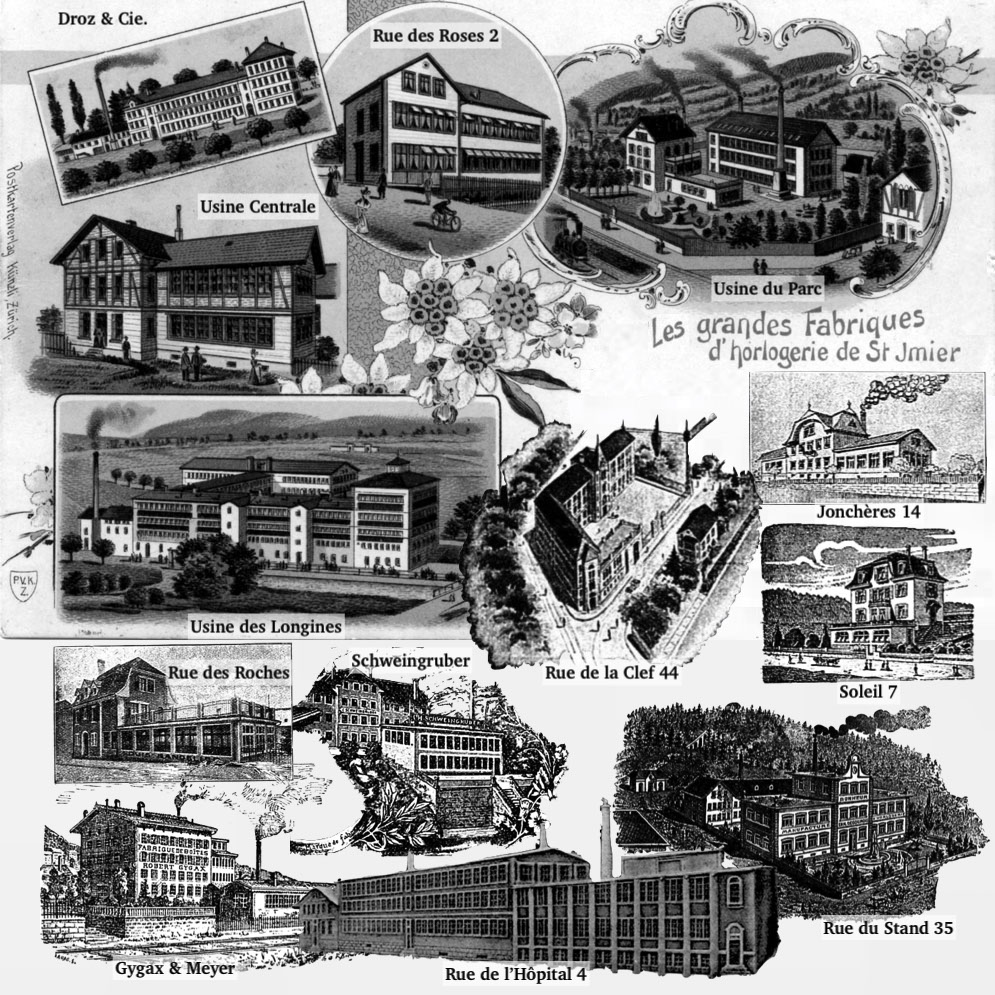

Les Grandes Fabriques d’Horlogerie de Saint-Imier

This is part of a series of posts about Les Grandes Fabriques d’Horlogerie de St Imier. Due to the detailed and complicated research required, it will likely take months to complete, so please subscribe to the Grail Watch newsletter to be kept up to date!

- Introducing the great watchmaking factories of Saint-Imier

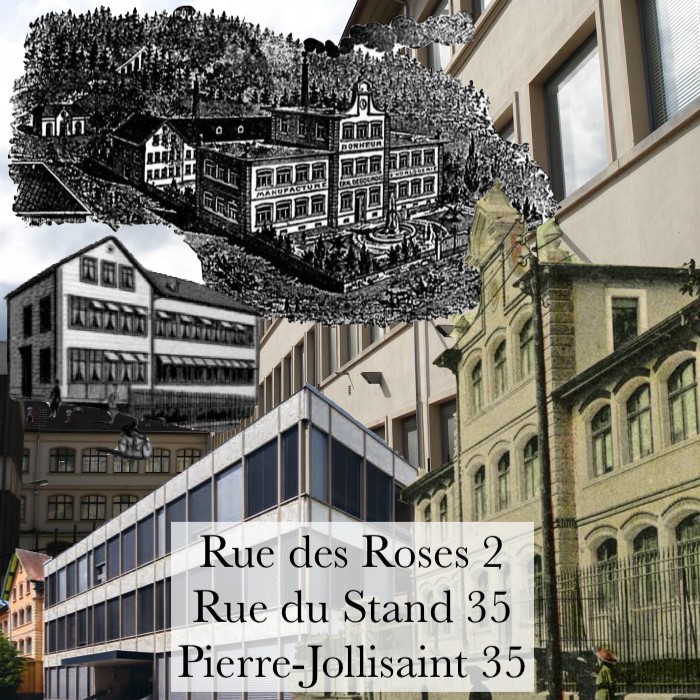

- The Evolution of Watchmaking Architecture: Rue des Roses 2 and Rue du Stand 35

- Excelsior Park: Usine du Parc

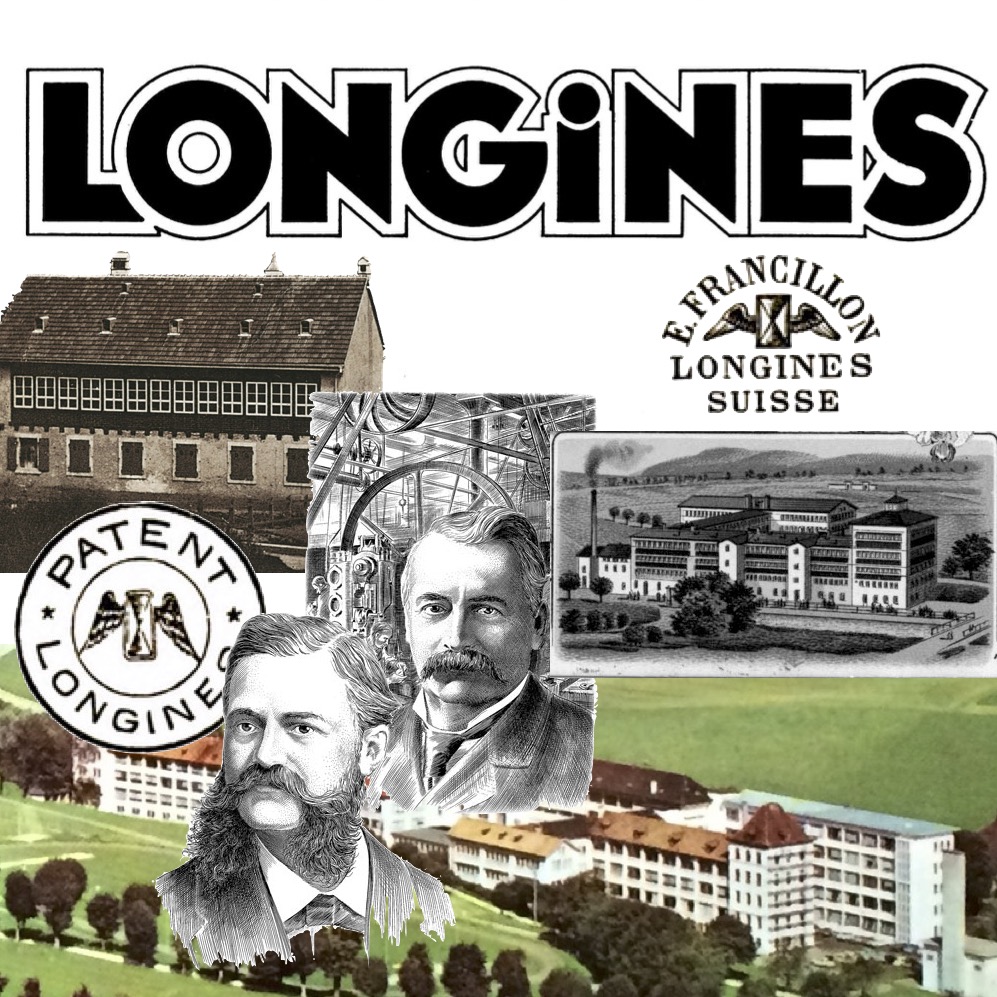

- The Rise of Mass-Produced Watches at Les Longines, Saint-Imier

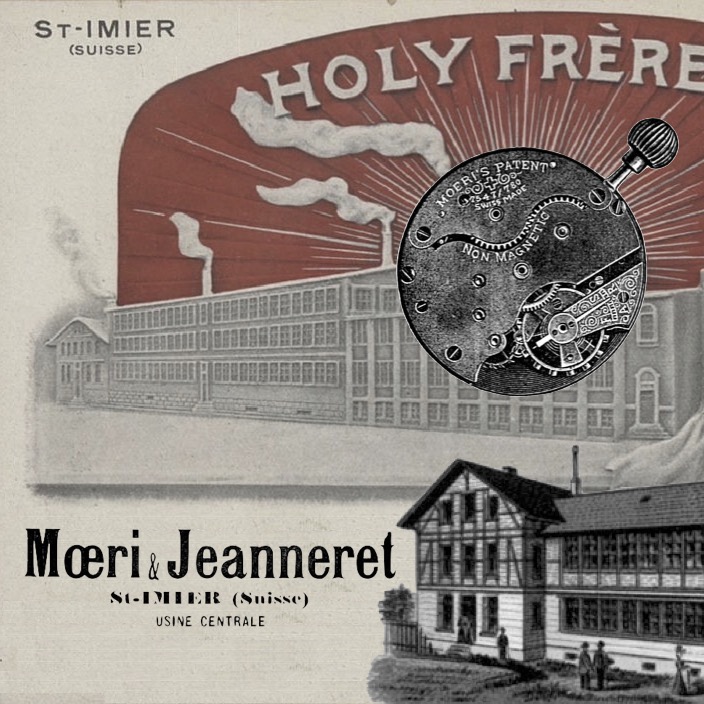

- From Atelier to Factory: Usine Centrale, Saint-Imier

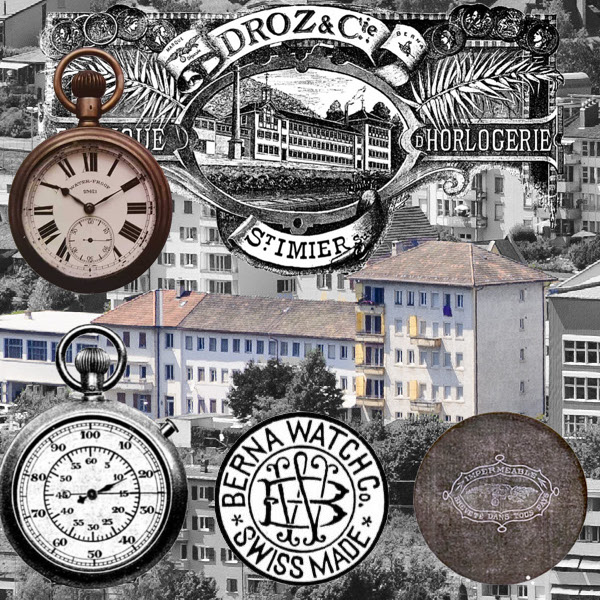

- Droz and Degoumois: Berna Watch Factory

- Rue de la Clef 44: Fritz Moeri’s Moeris

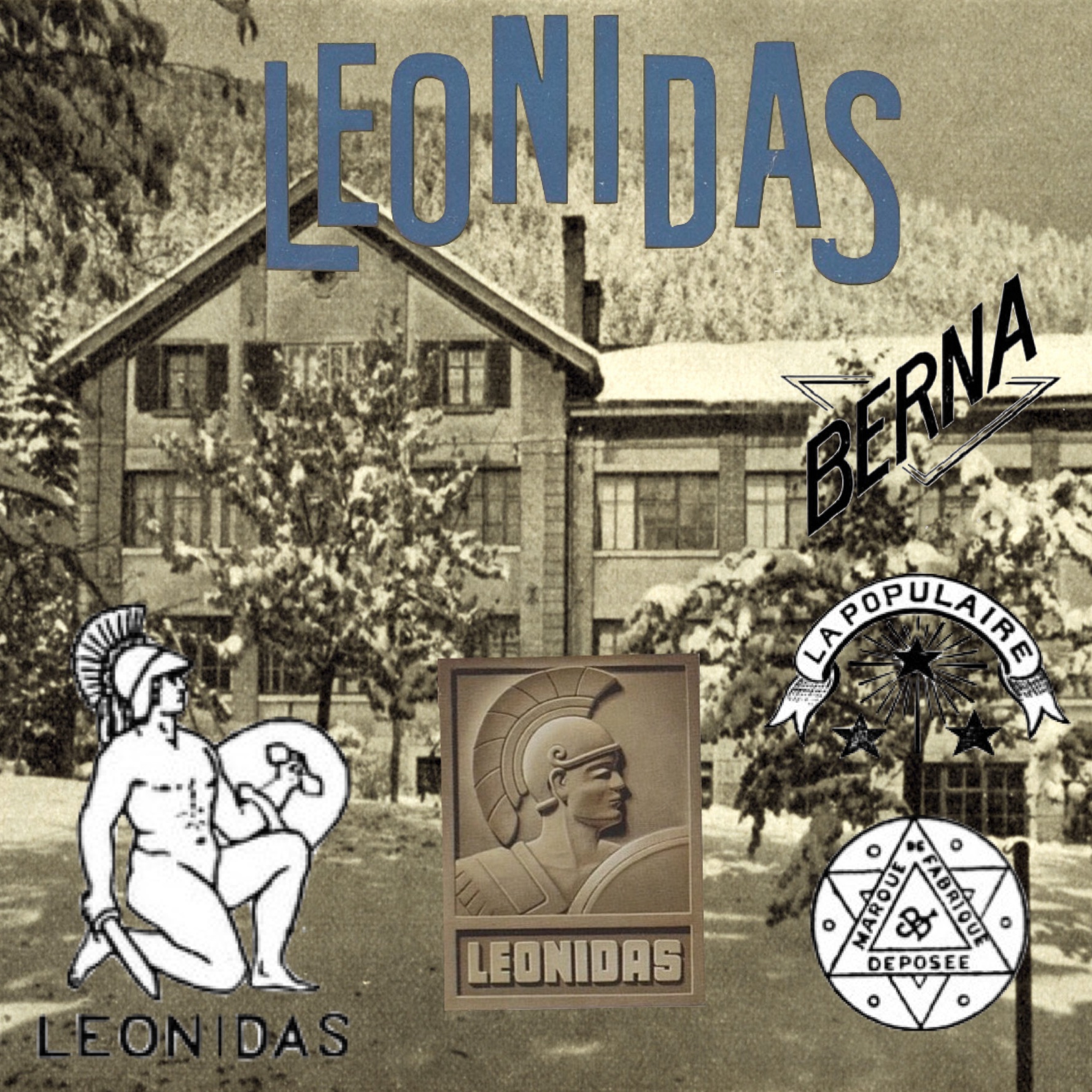

- The Rise and Fall of Leonidas and the Beau-Site Factory

- Gygax & Meyer

- Schweingruber

- Smaller Factories of Saint-Imier

Each of these factories has a story to tell, both about the products produced there and the watchmaking industry at the turn of the 20th century. We will explore the transition from home to factory, the rapid rise of corporations, the transition from water and steam to electric power, the great Jeanneret family, and more!

The Battle for Power in the Industrial Revolution

Although steam power was known as early as the first century CE, it was Englishman Thomas Savery who is credited for bringing it to the first industrial use. At the turn of the 18th century, Savery and Newcomen introduced practical steam-powered pumps in England, enabling exploitation of submerged coal mines across Europe. Then James Watt came along in the latter part of that century with vastly-improved efficiency, enabling steam-powered transportation and milling machinery. Finally we must consider the massive engines invented by George Henry Corliss, which could be tuned and adjusted to handle fine textile work as well as heavy presses.

Steam power had many advantages, but chief among these was portability. Water-powered factories were dominant throughout the 19th century, and these are one reason that towns from Waltham in Massachusetts to Schaffhausen in Switzerland developed watchmaking and other heavy industries. Such it was in Saint-Imier, where Ernest Francillon located his Longines factory down in the valley along the river instead of closer to town. As we will discuss in our next article, Francillon’s expansion was inspired by the 1876 International Exhibition in Philadelphia, where the American Waltham and Elgin watch companies showed mass production of interchangeable parts.

But Waltham and Elgin did not rely on water power. That same exhibition featured Corliss’ massive steam engine, which could be located anywhere with sufficient fuel. Thus, steam would prove more practical at any scale, and soon this was the driving force for industrialization. Although there were many promising power sources on the rise in the 1880s, including compressed air, water, and electricity, it was steam power that would soon dominate.

A new rail line (with steam locomotives) was constructed in the Saint-Imier valley in the 1870s, allowing the towns of Saint-Imier, Villeret, Cortébert, and more to connect to the main lines in La Chaux-de-Fonds and Bienne/Biel. It ran along the southern border of town where the land tumbled down into the valley holding the Longines factory, sawmill, and other water-powered industries. Rue du Pont ran down to the river from a high bluff by the railroad tracks known as Les Ages. This spot, close to town but on the other side of the tracks, would become the home of the watchmaking factories later known as Excelsior Park and Moeris.

Two large houses and a barn had already been constructed along Rue du Pont in Saint-Imier by 1857, and a factory with a steam boiler was added by 1879. Given this timing, this “usine a vapeur” may have been equipped with one of the new Corliss engines or it might have used an older style. A few companies had appeared in Geneva in the 1870s to construct steam power plants for factories, and two similar factories were built in La Chaux-de-Fonds at that time.

This factory was used by producers of dials and cases in the 1880s and 1890s, tasks that required the steady power of a steam engine. One example is the firm of case maker Christian Baehler, which remained in the factory from 1890 through 1908. Their specialty was hard steel cases with screw-down backs, which would have been impractical to produce without steam power.

The Jeanneret Brothers of Saint-Imier

Watchmaker Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret moved to Saint-Imier around 1868 from La Chaux-de-Fonds at the urging of his brother in law, Fritz Thalmann. He established a family watchmaking business there (as we shall cover in a future article) and became a successful etablisseur, assembling watches for Thalmann to distribute. These watches were sold throughout the British Empire under the Colombe and Pigeon brands, and the business was successful enough to continue even after Jules-Frédéric’s death in 1892. Jeanneret’s firm was taken over by his nephew Samuel, while his sons went on to build the watchmaking brands, Excelsior Park, Moeris, Leonidas, and Berna. Along with the Agassiz/Francillon family, the Jeanneret clan was critical to the continuing relevance of Saint-Imier in watchmaking.

The steam-powered factory on Rue du Pont was purchased by Jules-Frédéric Jeanneret and Fritz Thalmann in 1885, and this would become home to the next generation of the Jeanneret family. The eldest Jeanneret son, Albert, was eager to adopt the industrialized mass-production of watches, as pioneered in the town by Ernest Francillon, Jacques David, and Alcide Droz. So in 1889, he set up a new firm with his brothers, Henri and Constant, at the Rue du Pont factory.

The curve on Rue du Pont where the new Jeanneret home and factory was located overlooked the valley, with the wild Chasseral and the ruins of the Erguel Castle beyond. This estate became known as Le Parc, and the factory was thus originally called Usine a vapeur du Parc, highlighting the use of steam power there. This would later be shortened to Usine du Parc.

La Fédération Horlogère, August 1, 1891

Early advertisements shows the Jeanneret brothers offering their manufacturing capacity and watchmaking capabilities to others. Perhaps they hoped to be a manufacturer first, rather than a watchmaking brand. But they quickly changed their focus, embracing the family’s Colombe brand and its 1866 date of inception. Albert Jeanneret’s 1891 patent CH3364 would give the company not only its own product but also its logo: A stylized bridge in the shape of a J that would be the hallmark of the company for decades.

It is likely that the brothers were also leveraging the chronograph patent CH359 licensed by their mother from Alfred Lugrin of l’Orient in 1894. He would go on to found Lémania, a competitor throughout the 20th century for the Jeanneret’s Excelsior Park and Leonidas factories.

The most successful product of the Jeanneret family in the 1890s was a 30-minute stopwatch (“compteur de sport”) advertised under a new brand: Excelsior. Protected by patent 3364, the Excelsior stopwatch became so well known that the name would displace Colombe and Diana and become the primary brand for the factory. The brothers earned wide acclaim at that time, with medals in Antwerp, Paris, Chicago, and Geneva for their fine chronographs and stopwatches.

Henri Jeanneret-Brehm and Excelsior Park

Albert Jeanneret also partnered with Fritz Moeri, a former apprentice from his parent’s factory, on a new venture. Moeri & Jeanneret would produce inexpensive anti-magnetic watch movements based on Moeri’s patent at Usine Centrale, and this became Albert’s primary focus from 1894 until his death in 1899. Henri and Constant remained in charge of the factory at Usine du Parc, now called Jeanneret Frères. In 1904, Constant left to focus on his Junior brand before purchasing the Leonidas Watch Factory across town in 1912.

Learn more about Moeri & Jeanneret’s Usine Centrale.

The middle child, Henri Jeanneret-Brehm was a capable manager and watchmaker. He took over the company in his own name in December 1901 and navigated the economic turmoil before and after The Great War. Like his brother Constant Jeanneret-Droz, Henri added his wife’s surname to his own once he was married, though I was unable to identify his wife’s name.

Jeanneret-Brehm struck deals with some of the best-known names in horology, supplying chronograph movements to Zenith in Le Locle and Girard-Perregaux and Gallet in La Chaux-de-Fonds, among many others.

But the company’s focus was always on the production of excellent high-end stopwatches for various sports, specifically including football, rugby, polo, hockey, and boxing. The company would later register the Speedway brand for the nascent world of motor racing.

It was Gallet that provided funds for Jeanneret-Brehm to expand production, purchasing the firm of H. Magnenat-LeCoultre of Le Sentier in 1911. A well-known producer of minute repeaters under the brand name “Le Risound”, Magnenat-LeCoultre gave Jeanneret-Brehm a complimentary product and access to the skilled watchmakers of the Vallée de Joux. At the time, minute repeaters and chronographs were in vogue, and many companies were focused on producing them in higher volumes than was previously possible.

Gallet is also said to have encouraged the company to adopt the anglicized name Excelsior Park, which would prove popular in Great Britain. Gallet had recently purchased the Electa watch factory in La Chaux-de-Fonds but relied on Jeanneret for their chronograph and stopwatch movements. This brought Excelsior Park to Gallet’s markets in China, India, and Japan. Interestingly, one of Gallet’s distributors was Kintarō Hattori, founder of Seiko, which would displace Excelsior Park and Heuer-Leonidas stopwatches in the 1970s.

By the 1910s, the brand was so well known that it was experiencing counterfeiting and appropriation in some markets. Indeed, a 1902 chain letter scam (one of many that swept Europe around the turn of the century) promised as a reward a watch produced by “Excelsior” in La Chaux-de-Fonds!

Although the factory was built for steam, it was converted to electricity in the first half of the century. The signature steam boiler, highlighted in the 1900 postcard engraving, is still visible into the 1920s but was certainly gone by 1949. The factory was never expanded, either, even as Albert Jeanneret’s partner Fritz Moeri built his huge multi-wing factory in stages across Rue du Pont. It was literally overshadowed by Moeri’s building, though the steep valley still let in plentiful natural light. It is likely that the second facility in Le Sentier provided additional production capacity without calling for expansion in Saint-Imier.

Excelsior Park in the 20th Century

Henri Jeanneret-Brehm was succeeded by his son Robert-Henri Jeanneret around 1918 and he died in 1932. By that time, the Jeanneret factory was commonly known as Excelsior Park, and it would remain in family hands for decades. After Robert-Henri, who celebrated the 100th anniversary of the company in 1966, it passed to the fourth generation, Robert-Edmond Jeanneret, who oversaw the company until 1985.

La Fédération Horlogère, June 8, 1939

Excelsior Park itself remained firmly dedicated to stopwatches, even as the company expanded production of compact chronograph movements for partners. One novel innovation in the 1920s was a sealed compartment of spare parts hidden inside the movement itself beneath a plate that resembled a bridge. The company also continued to use the J-shaped barrel bridge on most movements.

Excelsior Park patented a beveled tachymeter scale around the dial in the 1930s, and this was a signature element on many of their watches. Many also featured a spiraling scale inside the counters, as seen on many chronographs from this era. Excelsior Park also patented the open diamond-shaped hands seen on many models, which provided both legibility and visibility of the scale beneath.

Especially after World War II, the Excelsior Park brand focused on stopwatches for sport, science, and industry. We see some novel products in later decades, including a specialized “Totalisator” to calculate individual and cumulative production time, which won first place at the Swiss National Exhibition in 1964.

Excelsior Park resisted a switch to true mass production and inexpensive stamped or plastic components, sticking to finely-finished jeweled movements. Across town, Leonidas had become a mass-marketer of cheap stopwatches, providing Heuer complete coverage of the sports timing market after the acquired that company in 1964.

By the 1970s, Excelsior Park was extremely reliant on exports to the American market, but the end of the Bretton Woods system with the Nixon shock in 1971 soon doubled the cost of Swiss watch exports. Seiko was on the rise at this time as well, producing inexpensive but high-quality mechanical stopwatches at a fraction of the cost. By 1975 Excelsior Park was nearing bankruptcy, and production ended on March 31, 1983. The remaining stock of movements was purchased by Gallet and Revue Thommen, but the factory remained closed and the company was liquidated on December 12, 1985, just 6 months after the death of Robert-Edmond Jeanneret.

Image: CEFF

The Grail Watch Perspective

The demise of Excelsior Park was as unusual as its rise. It was not a victim of quartz or electronic watches so much as a misunderstanding of its own market. Stopwatches were purchased by companies and organizations like schools that were more sensitive to price than to quality or longevity. And pin lever (Roskopf) movements, plastic cases, and cheap finishing didn’t scare away these customers. They were even happy to adopt Japanese stopwatches if the price was right.

By remaining apart from the wristwatch market, Excelsior Park never developed new features like automatic winding that saved chronograph makers like Breitling, Heuer, and Zenith in the 1970s, and they did not attract interest during the 1980s mechanical watch revival like Valjoux, Lémania, or F. Piguet. Instead, Excelsior Park closed its doors and was auctioned off. As noted in a 1984 newspaper article, “you can’t sell a luxury motorsport timer; that does not make any sense!” Excelsior park was simply a victim of “excellent quality at too high a price.”

Reference Materials

Albert Jeanneret & Frères

Henri Jeanneret-Brehm and Excelsior Park

1902 Excelsior Chain Letter Scam

This 1902 “snowball scam” is an example of the type of chain letter scams seen widely across Europe at the turn of the century. It combines elements of a pyramid scheme and chain letter, promising to reward those who recruit their friends. Because the Excelsior brand was becoming well known at the time, it was appropriated by the scammer, along with the well-known watchmaking city of La Chaux-de-Fonds. There were watches to be had, apparently, and an unsuspecting merchant from that city, Paul Debrot, was accidentally identified as the perpetrator.

Here in town and perhaps also in the provinces, many people have received a communication that we could receive at the post office a registered letter against reimbursement of florins 2.67 1/2. Shipping was made by the “Excelsior” watch factory in La Chaux-de-Fonds. Many people have been fooled before, although they have never heard of the existence of an Excelsior watch factory. One receives, a circular well written in Dutch, with five coupons, each giving the right to one or more watches of the value of 45 guilders, on condition that one places all these five coupons with his friends, who must also give in their turn. fj. 2.50 to the factory to become the happy owners of a voucher with five coupons.

So therefore a snowball. The purpose of this sales system is: the advantage of buyers! ! ! so says the circular; but we doubt that the people who will be fooled will think the same.

This is not the first time that Switzerland has been asked to clean up the markets.

Die Schweizerische Urhrmacher-Zeitung publishes, in its September 1 issue, the protocol of the meeting of the central committee of the Association of Swiss Watchmakers, held in St. Gallen on July 14.

We read the following passage:

We had relations with the Association of Dutch Watchmakers in Amsterdam over the so-called “snowball” sales system, where “Excelsior” pocket watches were sold by this kind of business. These watches are delivered by a certain Paul Debrot, merchant-tailor, to La Chaux-de-Fonds.

Precisely moved by the unfair accusation that was thrown at his head, Mr. Paul Debrot, watchmaker, in La Chaux-de-Fonds, wrote the following letter to the president of the Association of Swiss Watchmakers and a copy of the said letter to the newspaper (published to him; the protocol of the meeting of St. Gallen. This letter which its author asks us to publish puts all things in their place.

La Chaux-de-Fonds, September 17, 1902.

Mr. Paul Keller,

president of the Zentralverbandes Schweizerische Urhrmacherzeitung,

Sir,

I read in the supplement to n ° 17 of the Schweizerische Urhrmacherzeitung, the protocol of the meeting of your committee of July 14, 1902, in which the commercial procedures of a named Paul Debrot, merchant-tailor, in La Chaux- de-Fonds.

I declare that I have nothing in common with the said merchant-tailor, except the name, and I ask my numerous and good customers in Switzerland not to confuse my manufacturing house, founded in 1892, with the traffic beginning quite recently with the said merchant-tailor, whose first name is Arthur.

Please accept, Mr. President, my warm greetings.

Paul Debrot

watch manufacturer.

The End of Excelsior Park

The end of Excelsior Park was well-documented in the Swiss press in the early 1980s. Roland Carrera’s work for l’Impartial in particular gives us an excellent perspective on the events and reasoning behind the closure of the company. It is particularly sad that Robert-Edmond Jeanneret, the fourth-generation CEO, would die just as his firm was collapsing.

Thank you very much for this interesting and well-founded article! about Excelsior Park!

Thanks for the kind words, and of course for your own excellent work!

Thank you very much for this interesting and well-founded article! about Excelsior Park!