The Bulova Accutron was the most important watch of the 1960s, bringing a new level of accuracy and technology and shifting the balance of power in horology from Switzerland back to the United States. It was also a dead end, delaying the development of other electronic watches and distracting the American and Swiss industries from the rise of quartz. How did something with such promise fail to have a lasting hold on the market?

Listen to The Watch Files episode, “How the Bulova Accutron Disrupted the Swiss Watch Industry“

Electric and Electronic Watches in France, the USA, Germany, and Also Switzerland

Image: New York Times, June 8, 1952

The Swiss industry was dominant after World War II and did not have much tolerance for new watch movement concepts. When the French LIP and American Elgin companies promised a battery-powered watch in 1951, it was seen as an attack by the Swiss. It was. Rather than re-build a mechanical watchmaking base after the war, France, Germany, and the United States focused on electronics. And once production got underway in the 1960s, this would become a major problem for the Swiss.

Swiss engineers were interested in electronic timekeeping, and had been involved in development of quartz and electronics. But dominant companies are rarely interested in disrupting their own market. So it is logical that challengers in France, Germany, and the United States would play a key role in creating alternatives to mechanical watch movements.

While LIP and Elgin struggled in public to develop their electric watch, another American firm, Hamilton, was quietly working on a similar design. Their first electric watch, announced in 1957, was much more primitive than the LIP and Elgin designs but a futuristic triangular case, and an appearance on the wrist of Elvis, gave the Hamilton Ventura a huge marketing boost.

Electric watches from Hamilton, Elgin, and LIP (and many others later) are characterized by their use of a battery for power, an electromagnetic coil which transfers this energy to the balance, and a conventional gear train. Some use mechanical contacts to switch the current on and off while others use a diode or simple electronic circuit with a transistor. Conceptually, the battery and coil replace the mainspring, barrel, and impulse pallets, with the rest of the movement components mostly unchanged fro mechanical watches. These components provided more consistent energy flow, which should improve timing accuracy, and would run for months or years without use.

Electric watches never lived up to their promise. The earliest models from Hamilton mounted the coil on the balance, where it was easily damaged, and had thin, fragile wires that were susceptible to sparking. LIP’s technology used fixed coils and a diode but required two batteries. These issues damaged the reputation of electric watches. By the time diodes and transistors came into wide use, tuning fork and even quartz movements were ascendent and the opportunity for electric watches had passed.

Technically, any watch using an electronic component can be characterized as an electronic rather than electric watch. So the coil-operated watches with a diode or transistor were often marketed as electronic, even though they had little in common with “electronics” as we know them today. Most people today would consider any watch with an electromagnetic coil, oscillating balance, and no integrated logic circuits to be an electric watch. For the sake of clarity, we will use this term as well.

Image: Europa Star Eastern Jeweller 129, 1972

Max Hetzel’s Tuning Fork, From Basel to New York

Image: Barbara Young-Hetzel

Although Swiss, Max Hetzel was not an industry insider. He was hired by Bulova in 1950 to assist in automation of their production in Switzerland, and was asked two years later to study the feasibility of the LIP/Elgin electric watch. Hetzel determined that an electric watch would be no more accurate than a conventionally-powered mechanical watch, since it still used a similar balance and oscillation frequency. Instead, he suggested using a tuning fork operating at acoustic frequencies.

Image: Bulova

Ade Bulova was personally very interested in the tuning fork watch concept and directed Hetzel to take on the project. He sent Hetzel some of the new transistors that had recently appeared on the American market in 1952 and 1953, and these enabled Hetzel to build a prototype movement on a block of wood. He submitted a patent on the concept on June 19, 1953.

Hetzel was able to complete a working prototype of a tuning fork watch by November 1954, and Ade Bulova took it back to New York after a month on Hetzel’s wrist. He soon built another eight prototype watch movements to test, but corporate politics got in the way. The company transferred his work to their New York headquarters later that year, with William Bennett taking over management of the project. By 1959, 100 more prototypes were built at the direction of new Bulova President Harry Henschel, but these proved less capable than Hetzel’s original prototypes.

Frustrated, Hetzel petitioned for relocation to continue his work, and difficulties in development pushed Bennett to bring him to Jackson Heights to develop the concept. Hetzel started work in New York on June 3, 1959 but was initially assigned to repair and diagnose the American prototypes. Determining that the issue was a sticky pawl due to degraded oil, the Bulova team added a second finger to solve the issue. With this issue out of the way, development sped up and the tuning fork movement was deemed ready for production.

Image: Europa Star Eastern Jeweller 62, 1960

The tuning fork movement was christened “Accutron” by Bulova, highlighting its accuracy (guaranteed by Bulova to one minute per month) and the electronic components (a single transistor) used in its construction. Seizing a marketing opportunity (and the military connections of Bulova Chairman, famed WWII General Omar Bradley) the company arranged for the Accutron movement to be used by NASA in prototype satellites and space missions.

Image: New York Times October 21, 1960

An Accutron timer was placed in the Explorer VI and Explorer VII unmanned orbiters in 1959, even before the watch was launched. The latter had a bit of an issue on October 14, 1959 when a component unrelated to the Bulova timer failed to switch transmission of data, but it was used successfully aboard Explorer XI on April 27, 1961. Accutron timers and watches would later be used on satellites (Telstar, Tiros, Syncom, Pegasus, and LES), in spacecraft (Explorer, Mercury, Gemini, Agena, and Apollo), and on the wrists of astronauts.

Bulova officially announced the Accutron watch on October 25, 1960, and it was an immediate sensation. Unlike the primitive electric watches from Hamilton and Lip, the Accutron boasted better timekeeping and was fully developed for production. Indeed, the original Bulova Cal. 214 would be produced in massive numbers and many are still running today. They were also obviously different, right down to the signature “hum” of the movement, which quickly became a bragging right for the owner. Bulova probably sold more Accutron watches based on owner evangelists than through their prodigious advertising campaigns!

The Accutron went on the market in 1961, and sales were strong from the start. The company boasted over 100,000 sales by 1963 and over 350,000 sales by 1965. The New York company was soon one of the highest-grossing watch makers, reversing a strong trend toward Swiss watches that had brought calls for protectionist tariffs in Congress and an anti-trust suit just a few years before. Now it was the turn of the Swiss companies to worry about their future.

The United States had never been a large consumer of luxury watches. Most Americans only purchased an upscale watch as a gift or to commemorate a significant milestone, and they strongly preferred domestic brands. Timex successfully brought inexpensive watches to the rising middle class, and this further eroded the American market around 1960. But the Accutron reversed this trend, bringing customers back into jewelry shops. The American consumer was spending money on high-end watches for the first time, and it skewed the entire watch market.

Perhaps no Bulova Accutron model is better remembered than the so-called Spaceview. It featured a transparent dial, showing the tuning fork in action alongside the colorful electronic components. These became so popular that regular models were often converted with transparent aftermarket dials, and this remains a popular modification even today. In fact, to many people, the transparent dial is the signature of the Accutron, rather than the tuning fork!

Bulova added a date complication in 1967’s Cal. 218, and a day-date model in 1969. That year also saw the creating of a dive watch, the first electronic watch suitable for use under water. For the first time, there was an Accutron model for every mainstream market niche, and there was no competition for the accuracy of Bulova’s watch. No longer sold as a futuristic space-age trinket, the Accutron was the most accurate and usable watch on the market, head and shoulders above the simple electric watches offered by others. And it was far more affordable than high-end automatic and high-beat Swiss mechanical watches.

The “Mini Accutron” appeared in 1970, operating at 480 Hz, along with a dual-timezone version for the Astronaut Mark II. Another multi-time version, the Universal Zone Timer, appeared in 1972. The final Accutron movements, a mini oval movement and 10.5 ligne version, came in 1973. All of these were designed to expand the Accutron to every niche in the watch market but no amount of expansion could head off the rise of quartz.

In December, 1971, Bulova launched the Accuquartz. This was a hybrid movement, which paired an early quartz crystal with the proven Accutron mechanism. Bulova produced it in volume, selling it for just $395. The Accuquartz became the first quartz watch available in America, and the first priced low enough for average buyers. But quartz digital models soon appeared, and the Accuquartz could not compete with American electronic components produced in volume.

Bulova sold over 5 million Accutron watches through the 1970s, but production would not last even 20 years. By 1974, the Accuquartz was retired and Bulova began cutting the price of the Accutron. It became a low-priced quartz alternative after 1975, and production ended around 1977. Unsold stock remained available at bargain prices for a few more years, a remarkable turn of events for the once sought-after watch!

How the Tuning Fork Escaped Bulova’s Hands

Despite resistance from the makers of mechanical watches, the Swiss were working on electric watches in the 1950s as well. André Beyner (who would later lead Ebauches SA and the development of the Delirium) and René Besson were working on prototype battery electric watches as early as 1952. Beyner mentioned a prototype in 1953, but they faced many difficulties bringing it to market. They were finally able to get a Swiss electric movement into production in 1960 at the Landeron factory in Neuchâtel, planning to make a splash at Basel the following spring. But the news in 1961 was dominated by the announcement of the Accutron and Landeron’s Cal. 4750 failed to take hold. Still, Ebauches SA continued developing electric watches and the ETA “Dynotron” line would see three generations of production.

In the late 1960s, buoyed by strong sales of higher-priced watches in the United States as well as a favorable exchange rate, American companies were buying their Swiss competitors. Bulova purchased Universal Genève and Recta, Hamilton took over Büren and moved production to Switzerland, and Zenith bought Zenith! This saw the first Swiss Accutron models launched, using the Universal brand. Bulova also leveraged their decade-long partnership with Citizen to begin Accutron production in Japan.

In 1968, Bulova licensed the Accutron patents to Ebauches SA so they could produce a tuning fork movement of their own. One wonders why the company would do this, but perhaps they were hedging their bets as quartz technology rose to prominence. The Swiss were similarly hedging against the quartz technology they were already developing! Another reason might have been that the inventor of the tuning fork movement was already at work back in his home country.

Max Hetzel had left Bulova in 1963, returning to Switzerland to continue his work. He soon joined Ebauches SA, where he created the “Mosaba” (“Montres sans balancier”) tuning fork movement. This movement shared the same basic design, necessitating the patent license. It would go into production in 1968 and was used by Baume & Mercier, Certina, Eterna, IWC, Longines, Omega, Tissot, and Zenith. 1972’s Cal. 9210 featured a chronograph complication, the world’s first electronic chronograph movement. Hetzel later went to the CEH, where he created the ultimate tuning fork movement, the Megasonic for Omega.

Image: Europa Star Eastern Jeweller 129, 1972

How Quartz Derailed the Tuning Fork

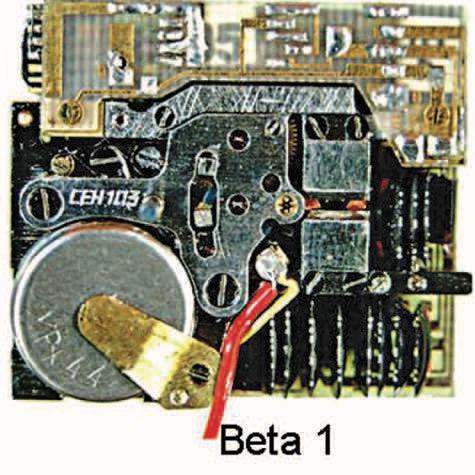

Although the tuning fork watch was the pinnacle of horology by the 1970s, it was quickly sidelined by an even more exciting prospect: Quartz electronic watches. The CEH Beta 21 was shown to be capable of chronometer-level performance in 1967 and the Swiss industry rallied behind the concept of quartz timing. Longines announced the Ultra-Quartz on August 22, 1969, Seiko released their Quartz Astron for sale that Christmas, and production Beta 21 watches dominated the Basel Fair in 1970. This created an “Osborne effect” in the industry, with consumers assuming that quartz would push aside mechanical, electric, and tuning fork watches.

Unsurprisingly, it would take years to translate the excitement about quartz watches to meaningful commercial sales. Bulova’s “hybrid” Accuquartz was the first quartz watch with high volume and low prices, but it was a technological dead end. The initial excitement about LED and LCD digital and solar watches similarly dissipated. But Seiko and Citizen in Japan, Texas Instruments and Intel in the United States, and the Swiss-American Intersil were diligently working to develop inexpensive and reliable quartz movements. These companies quietly delivered the future around 1975, with an accurate 32 kHz quartz crystal module, an efficient IC, and a reliable stepper motor.

By 1980 (after a brief “thin watch war“), quartz had captured a significant share of the market and tuning fork and electric watches were eclipsed in the public imagination. Mechanical watches were seen as passé and watch companies were entirely focused on quartz. 1982 was the tipping point, when sales of quartz surged above all other watches for the first time and Swiss industry was in free-fall due to a decade-long currency crisis. But this was also the year the Swatch, Blancpain, and Breguet were launched, blazing the path forward.

The Grail Watch Perspective: Bulova’s Accutron Rocket

The rise and fall of the Accutron matches the trajectory of a ballistic rocket: It was one of the top-selling watches immediately after launch and changed the course of the American market and the entire watch industry. But it fell from grace just as quickly once quartz was established and production was halted in under 20 years. The technologies used in the tuning fork watch failed to take hold as well, even though the groundbreaking Beta 21 quartz used a similar motor, and the Accutron remains a curious oddity today. Despite its fast decline, however, the Bulova Accutron remains the most important watch of the 1960s!

References

- Bulova Accutron at Grail Watch Reference

- ESA Dynotron at Grail Watch Reference

- ESA Mosaba at Grail Watch Reference

- Electric Watches, CrazyWatches.pl

- Electric-Watches.co.uk

- The Accutron Watch Page

- Development of the Accutron, Barbara Young-Hetzel

- Engineering Time: Inventing the Electronic Wristwatch, Carlene Stephens and Maggie Dennis, British Journal for the History of Science, Vol. 33

A very interesting article, I prefer a good looking mechanical watch personally.

You wrote: “It was also a dead end, delaying the development of other electronic watches and distracting the American and Swiss industries from the rise of quartz. ”

I don’t think you’ve demonstrated that at all, and I don’t think it’s true! It is certainly true that the tuning fork movement was a technological dead end, in that no aspect of the technology has been carried forward into modern watches. The same is true of the other electric or “electronic” watches of the time.

But to claim that it delayed the development of other electronic watches and distracted the Americans and Swiss from the new quartz technology seems unfounded to me. True, the first to market was Seiko, but the Swiss were pursuing quartz technology by the late ’60s and were only months behind Seiko in launching a quartz watch – just as you point out in your article.

I think it is best to consider electric, electronic and tuning fork watches simply as interim technologies between the traditional mechanical, and the new quartz, watches. They were considered desirable because they never needed winding (even when not worn), and the more constant power source (compared with a mainspring) gave the potential for better timekeeping. Quartz watches provided all of those qualities, plus a radical improvement in timekeeping, such that these interim technologies – battery-powered non-quartz – had but a brief period in the spotlight.

I’m sure the author would agree that battery-powered non-quartz watches have their own fascination, and the finest of the Swiss tuning fork movements were ingenious, beautifully engineered and very impressive timekeepers, incorporating as they did advances such as X-shaped tuning forks which were immune to positional error arising from the effects of gravity.

Thank you for sharing your view on this. It is a subjective judgement and two people can see different things in the same evidence. I appreciate your perspective.

The spaceview accutron don’t have a «transparent dial ». They have no dial.

Thanks for that correction!

Thank you for such a comprehensive history of the Accutron. I am old enough to remember when it was introduced to the marketplace, and what a marvel of technology it was thought to be by the general public.