There are few names in the golden age of watchmaking as revered as Vénus, which produced some of the best chronograph movements of the 1940s. But the history of this small Swiss company is not well documented, and the story reveals the surprisingly-connected world of watchmaking at the time. Vénus rose and fell in just a few decades, but the legacy of their chronograph movements, especially the legendary rattrapantes used by Breitling, lives on.

Paul Berret: From Cornol to Delémont to Grenchen

Paul Berret was born in 1888 in Cornol, a small town in the district of Porrentruy, which juts north from the Swiss Jura into France. A migration of German-speaking residents followed the annexation of the Jura by the Canton of Berne in the 19th century, and this flow of populations created business opportunities. The Berret name was known in watchmaking in Cornol, but Paul Berret’s father opted instead to move the family to the bustling town of Delémont, where he became a wine merchant.

After his technical studies, Paul Berret opted to focus on watchmaking, a rapidly-growing field at the turn of the century. He moved to Grenchen and went to work for Adolph Shild SA, a prominent and growing maker of ebauches. It is said that Paul was very likable, and hid his focus under a veneer of carelessness. Still, he must have impressed his superiors, since he was rapidly promoted to become a technical director at A. Schild at about 30 years of age!

These were difficult times for the watchmaking industry. World War I drove a shift in production, and the introduction of wristwatches created new demand for smaller and thinner watch movements. Then the industry exploded after the war, leading to over-production and cutthroat competition. The ebauche industry was especially hard-hit. Companies like A. Schild and Adolf Michel in Grenchen and Fabrique d’Horlogerie de Fontainemelon, which had long resisted consolidation and government oversight, began to see things differently by 1920. Rather than weaken their position, consolidation could cement their control over the industry.

At the same time, new ebauche makers continued to spring up all across the Jura. The introduction of precision automatic lathes produced by companies like Müller in Soleure, Lambert and Matter in Grenchen, and Meyer in Reconvilier enabled smaller companies to produce complicated plates, bridges, and pinions. And nowhere was this more evident than the prolific workshops of Petermann and Bechler (Tornos) in Moutier.

The Fall and Rise of Watchmaking in Moutier

Some of Switzerland’s famous valleys are ideal for agriculture, while others are cursed with poor soil and interminable winter snow. The valleys between Bienne and Basel are a happy median, supporting small family farms for centuries. Moutier sits in just such a valley, known as Grandval for the beautiful mountains rising to the north and south. The valley was cut by the river Birse, which runs from Tavannes, through the gorge at Moutier, then to Delémont, and on to the Rhine in Basel.

Watchmaking came later to Moutier than the nearby Saint-Imier valley, with just a few watchmakers appearing there in the early 19th century. But the city erected its first factory around 1851. Located along the Birse on the western side of town, it soon employed a hundred or so workers engaged in roughing and finishing watch movements. It survived the periodic crises that marked the second half of the decade and expanded to the production of complete watches. By 1870, the Société Industrielle in Moutier was producing ebauches, movements, and even complete watches.

Other workshops soon sprang up, producing cases and dials in support of the town’s watchmaking activities. The Grande Fabrique du Nord, built in 1888, expanded the town’s watchmaking capabilities greatly, employing 700 to 800 workers after the turn of the century. And engineers like Nicolas Junker, André Bechler, and Joseph Pétermann created a precision machine tool industry in Moutier, which remains at the site of the western factory to this day as CNC leader Tornos.

Moutier was connected to Basel via railroad in 1876, to Tavannes and Bienne in 1877, and to Solothurn in 1908, making trade dramatically easier. And an 8.5 km long tunnel to Grenchen under the Grenchenburg mountain linked the two towns in 1915. What had once been a half-day journey to these neighboring cities became a simple commute by rail.

Watchmaking was expanding as well, with Léon Lévy Frères of Bienne acquiring the Fabrique du Nord and purchasing a large plot of land near the center of town in 1896. Soon a huge three-building factory complex was built for Léon Lévy (later known as the Pierce Watch Co.), employing as many as 1,000 workers, or 25% of the town’s population! Pierce would become famous as a “dissident” that resisted pre-war consolidation and invented the vertical clutch chronograph, and the factory became the new home of Vénus in 1960 and today is used by ETA!

Fabrique d’Ébauches Vénus

Paul Berret certainly saw the potential of precision automated tools, and his work at A. Schild undoubtedly connected him to many entrepreneurs in the industry. He likely worked with Victor Spozio, who used the Tornos and Petermann tools to produce precision components in a new factory in Moutier since 1918. When Spozio Frères failed in 1920, Victor Spozio took over the firm for himself. But his business was bankrupt again in 1924, with the factory offered for public sale on March 10.

Paul Berret and his brother Jean-Baptiste joined up with Otto Schmitz, a maker of watch cases in Grenchen, to purchase Spozio’s factory. On May 15, 1924, the trio officially registered Fabrique d’Ébauches Vénus in Moutier.

For most of its history, Vénus movements were manufactured in the former Spozio Frères factory at Rue du Midi and Rue du Viaduc in Moutier. The building still stands, and is home to Michel Imhof SA, a precision machining company very similar to the original tenant! Vénus eventually relocated to the Pierce factory in 1960, but the history of Vénus is inextricably linked to the former Spozio factory.

The arrival of an up-and-coming ebauche maker was greeted with joy in Moutier, which had seen its share of labor strife and ownership changes over the years. As noted in this article in l’Impartial, many workers were then taking the train to Grenchen each day to work in the factories there, and it was hoped that they would be able to stay in the valley. It is likely that Paul Berret moved his family to Moutier at this time as well, and he would remain in the town until his death in 1949. But many things would change for Vénus over the next 25 years.

Jean-Baptiste Berret resigned his position and returned to Delémont in July of 1925, just over a year after the founding of the company. He was replaced on the Vénus board by Kurt Henggeler, an industry veteran from Unterägeri who had married into the Gasser family of Bienne. At that time H. Gasser & Cie. specialized in compact movements for ladies watches, the very same market as Vénus!

The initial product range from the Vénus factory in Moutier focused on compact round and “form” movements. The Ranfft database shows a few early movement families from the company: A 5.75 by 8.5 ligne tonneau movement and an 8.75 ligne round movement. This latter was later notably used in conjunction with Eugène Meylan’s EMSA automatic adapter, perhaps the first production automatic movement! Other high-volume Vénus customers include two prominent German watchmaking associations, Alpina of Berlin and Zentra of Cologne. Just five years after its founding, and despite a series of economic crises, the new ebauche maker was thriving.

But one thing the young Fabrique d’Ébauches Vénus did not produce was a chronograph movement!

Vénus and Ebauches SA

Although Vénus was successful on its own, the landscape of Swiss watchmaking was changing. Brutal competition drained much of the profit from the ebauche market, and makers became desperate. They began shipping unfinished movements outside the country, a practice known as chablonnage, enabling German, French, American, and other competitors to squeeze Swiss watchmakers. This became a fixation of the industry in the late 1920s, and industrialists became worried that the government would step in before the entire industry was lost.

The Swiss watchmaking chamber had proposed the creation of a holding company for high-volume ebauche makers in 1923, a year before Vénus was founded, but the group was unable to reach consensus. Sensing an opportunity, the Fabrique d’Horlogerie de Fontainemelon purchased the innovative but struggling chronograph works of Charles Hahn in Le Landeron in 1925, and began approaching other small ebauche makers. Rather than allow Fontainemelon to simply buy a dominant position in the industry, the Society of Ebauche Manufacturers met again and agreed to consider the creation of an ebauche holding company. They hired the Swiss Trust Company to audit the finances of all 28 members (and many others besides) in order to decide how to allocate ownership shares of such a cartel.

Image: La Fédération Horlogère, April 11, 1928

On June 25, 1926, a conference in Neuchâtel was held to present the structure of “Ebauches SA”, a holding company for the mainstream Swiss watch movement factories. Rather than aggregating small makers into one that could be competitive, Ebauches SA would bring three of the already-dominant companies under one umbrella. Thus it was that A. Schild SA (ASSA) and Adolphe Michel SA (AMSA) of Grenchen and Fabrique d’Horlogerie de Fontainemelon (FHF) would be merged by the end of 1926. These three factories alone accounted for 75% of the production of ebauches among all 28 members of the Society of Ebauche Manufacturers, and it was hoped that bringing them together would force the rest of the industry into line. The owners of these three companies also received the majority of shares in Ebauches SA, along with bankers from Neuchâtel, Berne, and Bienne.

Ebauches SA spent 1927 solidifying its control of Swiss ebauche factories, using its 12 million Swiss franc war chest to purchase key companies. Hahn in Le Landeron was the first to be integrated, but it was already owned by founding member FHF, so this put even more control and money into the hands of the Robert family! The next to join was the newly-formed cooperative called Fabriques d’Ebauches Bernoises, which was comprised of five small ebauche factories: Hora in Cortébert, Aurore in Villeret, Fabrique d’Horlogerie de Sonceboz, and related factories in Porrentruy and Court. Felsa of Grenchen joined late in 1927, and they quickly purchased the Berger factory in Oberdorf.

Ebauches SA was the dominant producer of ebauches by March 1928, and the addition of ladies movement maker Vénus in Moutier drew little attention. Sydney de Coulon, an independent businessman who was then outside secretary of Ebauches SA, was added to the Vénus management team later that year, formalizing control of the company.

The Swiss economy was rapidly worsening, and it is likely that Paul Berret was lucky to strike a deal with the cartel when he did. Watchmakers were facing bankruptcy throughout 1928, and many ebauche makers quickly followed. Companies like Champion of Bienne, Exit SA of Lengnau, Welta SA of Bienne, Suza SA of Cortébert/Corgémont, Russbach-Hänni of Court, and Triumph SA of Grenchen were all dissolved by the banks and handed over to Ebauches SA that year. Bovet Frères of Fleurier and Optima SA of Grenchen both exited the ebauche business, selling their tooling to the cartel, and Ebauches SA went on to purchase the assets of defunct ebauche makers in Pieterlen, Bienne, Lengnau, and Delémont.

With Ebauches SA controlling 65% of all Swiss ebauche manufacturing by the end of 1928, nearly every watchmaker in Switzerland was brought in line. The mighty Eterna (Schild Frères) and Grana (Kurth Frères) of Grenchen, Unitas (A. Reymond SA) of Tramelan, and both Peseux factories agreed to partner exclusively with Ebauches SA by the end of 1928. All of these would later be absorbed into Ebauches SA or ASUAG.

In just four years, Paul Berret’s Fabrique d’Ébauches Vénus had risen as a maker of compact and form movements and been absorbed into the mighty Ebauches SA. Although the company would lose its way and slide into obscurity in the 1960s, the cartel allowed Vénus to rise to new heights in the mid-century period with a new and important product: Chronograph movements.

The First Vénus Chronographs

There was also an unrelated watch brand called Venus, run by the Schwarz-Etienne family!

Vénus changed dramatically under Ebauches SA. Kurt Henggeler, never too focused on Vénus, turned away to merge his Hera brand with Madewell and Argo in 1929. He was also increasingly involved with the Gasser family company into which he married, and their brands, Preciosa and Silvana. Henggeler would resign from Vénus in 1933. Otto Schmitz left the company at the same time, leaving Paul Berret solely in charge of Vénus, under Sydney de Coulon, now the Managing Director of all of Ebauches SA.

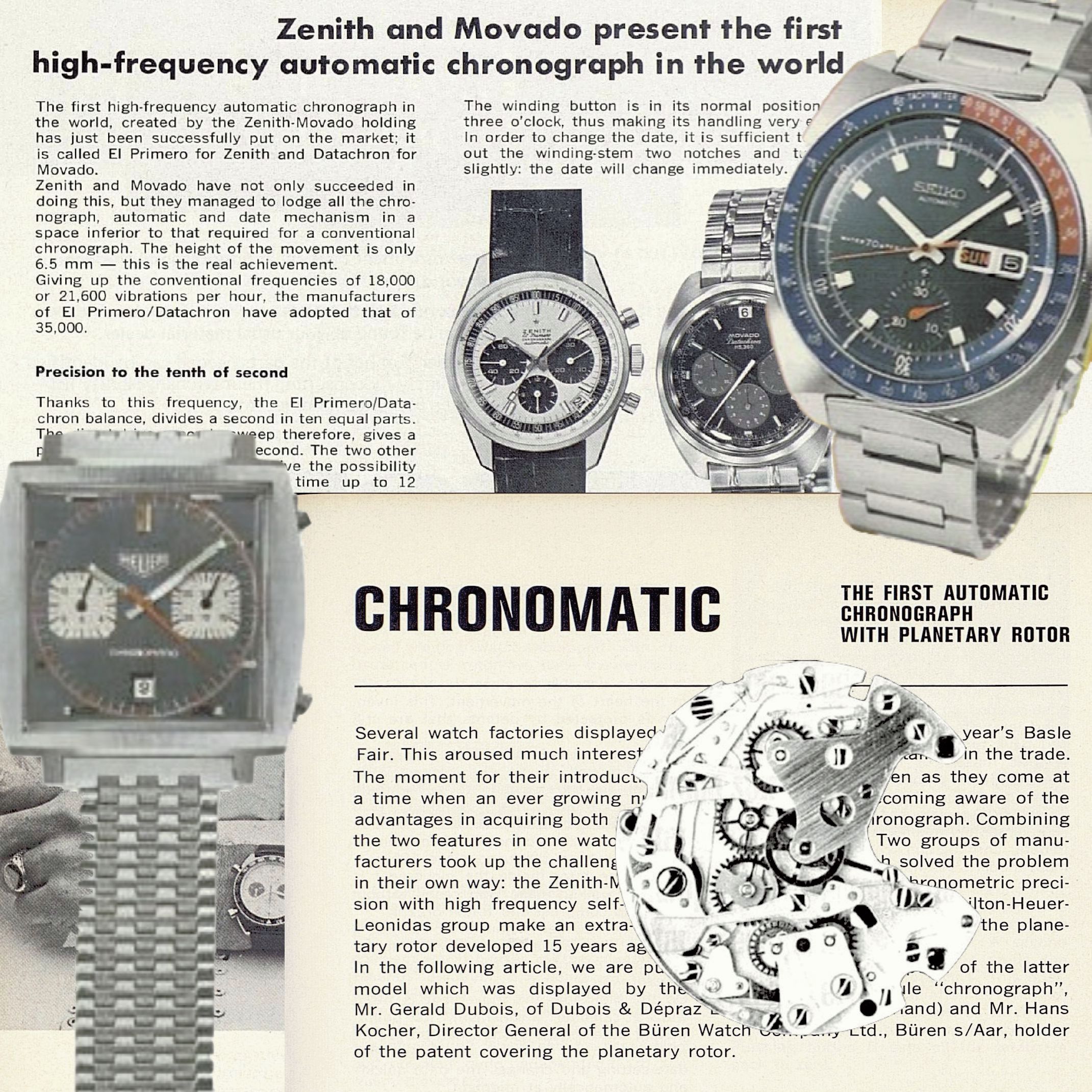

Ebauches SA and ASUAG were designed to restrain chablonnage in simple wristwatches, restricting sales only to members who accepted their production targets. A Swiss government entity known as Fidhor quickly acted to block the business of so-called dissident ebauche makers, with most falling into line or exiting the business by the end of the 1930s. But these rules did not apply to chronographs or other complicated watches. This provided an opportunity to escape the confines of the cartel, not just for members like Landeron and Vénus but also non-members like Valjoux, Universal Genève, and Pierce. At the same time, the needs of soldiers and airmen increased demand for wrist chronographs.

In 1933, Vénus produced its first chronograph movement. The simple Cal. 103 CHR was based on the 10.5 ligne Cal. 75 family, with a basic 60 second stopwatch function. With no minute totalizer or stop mechanism, the movement did away with the complex column wheel and used a simple system of cams to control the seconds hand that continually ran at center. It was essentially a standard watch movement with a flyback seconds hand.

Image: Benjamin Marcello

A similar mechanism would later be applied to the tonneau-shaped Cal. 131, resulting in the unusual Cal. 131 CHR. This was protected by patent 189192, which was not filed until 1936, but appears to have been produced earlier. These unusual movements revealed that Vénus was capable of producing more complex movements, and the legacy of the cam switching mechanism would become particularly important in the horology industry.

The next Vénus chronograph movement was somewhat more functional, though it still had a highly unusual design. The 1935 Cal. 140 features a central stopping chronograph seconds hand and adds a minute counter subdial at 6:00. But timekeeping is handled by an hour and minute hand in a subdial at 12:00, giving watches using the movement an unusual look reminiscent of a regulator watch. This movement is best remembered for the Gallet Multichron, which became somewhat popular with aviators during World War II. It was also used in a variety of American-market watches by Aristo, as well as brands like Berna, Doxa, Glycine, Juvenia, and even Ulysse Nardin. Today, Cal. 140 watches are often referred to as “regulator chronographs” though this is an inaccurate use of that term.

Swiss patent 159450 protected Cal. 140, and Vénus had applied for protection in 1931. This suggests that it was an early design somewhat out of the chronology of production. Cal. 140 was a monopusher and used an unusual five-column wheel for control using a single pusher at 4:00 on the dial. The chronograph mechanism resides entirely on the dial side of the movement, revealing that it is added to an existing movement rather than an integrated design. The movement was still somewhat roughly-finished and simplistic, and the odd dial layout was out of step with mainstream chronograph makers. Vénus was already working on the next generation movement, but Cal. 140 proved popular and would continue in production all the way through 1951.

The first real integrated chronograph movement from Vénus appeared in 1936 and was soon in full production. Cal. 170 was an inexpensive and extremely compact 12.5 ligne two-button chronograph movement that shared very little in terms of design with any previous or future Moutier movement. It utilized a Heuer-style oscillating pinion rather than a traditional horizontal clutch and was thus much less complex than other Vénus movements. But it still featured a column wheel for smooth pusher operation, unlike the cam switching Landeron Cal. 48 family which had wowed the industry on its introduction a few years earlier.

Perhaps the most notable feature of Cal. 170 was the continuation of the 6-12 subdial arrangement, though the hour and minute hands were moved to center. This makes easy to spot a Cal. 170 chronograph movement, though Valjoux and Pierce also produced “6-12” chronograph movements.

Image: Europa Star Trade Bulletin 15, 1936

Cal. 170 was used by Breitling, Heuer, Leonidas, Gallet, and many others in “popular” lower-priced chronograph watches. Breitling was so closely associated with Vénus Cal. 170 that this movement is often referred to as being a “Breitling calibre”. There may be some truth to this as well: Breitling may have produced watches for other brands or provided these movements to them. The new inexpensive movement was also enthusiastically embraced by Willy Breitling himself. A 1936 letter in Europa Star’s Trade Bulletin sees him equating it with the famous Kodak Brownie camera as a way to bring chronograph wristwatches to the masses, especially young people, at lower prices.

Although it was rejected in favor of movements with a more conventional layout after 1950, Cal. 170 made a huge impact on the industry, enabling the creation of a dozen different compact chronograph models sold at accessible prices through the 1940s. Many were used on the wrists of soldiers on both sides of World War II, and no doubt many remain treasured family heirlooms.

Image: Europa Star LRR 7, 1943

The Golden Age of Vénus Chronographs

The opportunity in wrist chronographs proved so compelling that Vénus largely focused on chronograph movements for the next decade. Vénus continued to work on chronograph mechanisms throughout the 1930s and introduced their first high-end chronograph movement by 1938.

The Cal. 150 family featured the popular 3-9 subdial arrangement and two buttons rather than a coaxial monopusher. But more important was the design: It was a modern integrated chronograph with high quality components. Cal. 150 measured just 13 lignes (29 mm) diameter, making it much more compact than competing movements from Valjoux or Universal/Martel and the same size as the revolutionary Longines Cal. 13ZN. It was also somewhat thinner than competing movements at 5.7 mm. The movement was an immediate hit, drawing attention from most major wrist chronograph makers and making Vénus the provider of choice for the next two decades.

Although Cal. 150 was important, it was still a bit unusual. The third wheel is oversized, moving the intermediate wheel to the side. And not all of the chronograph components are directly mounded to the main plate, so an additional chronograph bridge is attached to the barrel bridge. These same design elements are found on the related 14 ligne Cal. 175 family, which is one of the most celebrated chronograph movements of all time.

It is somewhat difficult to precisely say when any watch movement was launched, since years can pass between the design, patent, introduction to watchmakers, and mass production. Cal. 150 appears to have been designed and introduced earlier in the 1930s, perhaps as early as 1936, and was likely shown to prospective OEMs like Breitling around this time. We know that Cal. 150 was on the market by 1938, but it was likely introduced a bit earlier than this.

Image: Europa Star LRR_AL 26, 1944

1942 saw the launch of two key movements: Cal. 152 added a chronograph hour counter at 6:00 on the dial, while Cal. 179 added a rattrapante (split seconds) function. The latter was part of the 14 ligne Cal. 175 family, which was based on Cal. 150 but included many refinements. This coincided with a split between Breitling and longtime supplier Hahn in Landeron. Between 1942 and 1945, every Landeron-powered watch Breitling’s catalog was replaced by a new model using a Vénus movement.

Although the rattrapante movements do not appear to have reached production until 1943 or 1944, they quickly became a signature offering for Breitling, which had been an enthusiastic supporter of Hahn Landeron movements in the 1930s and focused almost exclusively on Vénus in the 1940s. The rattrapante Breitling Duograph, launched in 1943, was the halo model for the company, offering a feature no other company could match. The only other widely-produced rattrapante movements in this period were the oversized (39 mm) Valjoux 55 VBR, a monopusher, and the oddball Bovet and Dubey & Schaldenbrand “catch-up” movements. Interestingly, the latter company re-introduced refurbished Vénus tonneau movements in modern cases in the 2000s.

After the war, Vénus added calendar functions to their successful chronograph movements, including date pointers and moon phase indicators. The resulting movements were incredibly complex and desirable, with the legendary Cal. 190 (with rattrapante and moon phase) being perhaps the most sought-after today. These came with four subdials (like Cal. 190) or with day and month discs and a central date pointer. Although somewhat rare in the “golden age”, these chronograph movements reappeared in recent decades thanks to Jacquet-Baume SA (later called La Joux-Perret) in La Chaux-de-Fonds, which refurbished and re-created the classic Vénus movements in the late 1990s. These were used by many manufacturers in the 2000s, including Parmigiani, Panerai, and Maurice Lacroix.

Image: Europa Star Eastern Jeweler 29, 1955

Vénus was best-known for chronograph movements, but the company also produced other notable movements in the post-war period. Among these are Cal. 208, a 10.5 ligne small seconds movement with a central date hand, and Cal. 230, an alarm movement. The latter was especially significant as the alarm function was much more user-friendly than Vulcain’s Cricket or Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Memovox: It used a single barrel for time and alarm, had a simple pull/push crown to enable the alarm, and even featured a visual indicator of alarm status on the dial. Introduced in 1955 in the Nitella Alertic, it lagged a few years behind its rivals but was somewhat cheaper.

From Vénus to Valjoux: The Cam Chronograph

Although best-remembered for complex rattrapante chronographs, Vénus was also a pioneer in affordable complications. As mentioned, Calibres 140 and 170 brought the chronograph to the masses in the 1930s and 1940s at half the price of a Valjoux movement, and Vénus had experimented with cam-switching timers as early as 1933. But it was in-house rival Landeron (part of FHF within Ebauches SA) that was first to market with a full-featured cam-switching chronograph.

In 1936 Landeron began showing an inexpensive three-pusher 13.75 ligne movement, Cal. 47, that dispensed with the column wheel and used simple stamped steel cams to start, stop, and reset the chronograph. This was patented in 1939 and the follow-on two-button Cal. 48 was enthusiastically embraced. Willy Breitling, whose family firm had long relied on Landeron movements, extolled the potential of this inexpensive movement. Even though it was much larger in diameter, the Landeron movement would displace Vénus’ Cal. 170 thanks to its conventional 6-9 subdial layout and even lower price.

Despite the interruption of World War II, and perhaps inspired by the demand for cheaper chronographs, Vénus introduced their own cam-switching movement in 1948. Vénus Cal. 188 was another revolution in movement design, eliminating the column wheel in favor of stamped cams like Landeron’s Cal. 47 and 48. The Vénus movement was more conventional in appearance and operation than Cal. 170, despite being a bit over-sized at 14 lignes in diameter. Two years later, Vénus added a calendar to the movement, and even produced a version with a moon phase complication.

Paul Berret died on November 22, 1949 at the age of 61. In just 25 years he had guided Vénus to become one of the most respected makers of complicated watch movements. Just before his untimely death, Berret oversaw both the phenomenal Cal. 190 and revolutionary Cal. 188, and both are his legacy.

Cal. 188 was reduced in diameter in 1953, resulting in the 12.5 ligne Cal. 210. To this, Vénus added a real novelty: A dual-disc “big date” complication. Although mostly forgotten today, the “big date” Cal. 211 is as much a technological landmark as any other movement produced in Moutier: Vénus was four decades ahead of A. Lange & Söhne!

The success of the cam operated chronograph movements in the 1950s meant Vénus was outgrowing its modest factory on Rue du Midi. In the 1950s, the Swiss cartel relaxed its rules on Chablonnage to the extent that Pierce was able to procure more advanced movements from Ebauches SA members. No longer needing to produce their own movements, Pierce consolidated its operations and decided to close the aging Moutier factory. Vénus was quick to snap up the property, moving to the Pierce building at Rue des Fleurs 17 by 1960.

Seeing this line as the future of the company, Vénus stopped production of the classic column wheel movements in the 1950s. The company is said to have sold the tooling for Cal. 150 to the First Moscow Watch Factory, though I could not find corroboration of this. Regardless, we know that the company (also called Poljot) was producing the “Strela” with Cal. 3017, a copy of Cal. 150, by 1959. Vénus also offered to sell the tooling for Cal. 175, but it was ultimately the Tianjin Watch Factory in China that would purchase the movement, and it remains in production today as the Sea Gull ST19. Poljot purchased the tooling for Valjoux Cal. 7734 (likely also produced by Vénus) around 1974.

In the 1960s, Ebauches SA sought to consolidate its member companies. Valjoux had been purchased by the cartel in 1944 after the retirement of John Reymond, and Ebauches SA decided to merge the two chronograph makers in 1966. The Moutier factory remained in operation as a branch of Valjoux, though production of the remaining Vénus movements were cancelled.

Vénus cam-operated chronograph became was still in demand, however, as the public began demanding cheaper watches in the 1960s and 1970s, so Valjoux immediately revised Cal. 210 and reissued it as Cal. 7730. This was replaced by Cal. 7733 in 1969 and Cal. 7740 in 1972. A glance at the design and layout of these movements clearly shows this lineage, though each Valjoux generation is obviously quite different.

Valjoux hired young Edmond Capt in 1970, tasking him with creating a compact and inexpensive automatic chronograph movement. Fresh from watchmaking school in Le Locle and an apprenticeship at Rolex, Capt was inspired by the three-dimensional integration of Heinrich Stamm’s Eterna-Matic and the rugged reliability of the Vénus-derived 7730 and 7733. The result was one of the most successful and admired movement designs in history, the legendary Valjoux 7750. Although quite different from its predecessors, the lineage from Vénus to Valjoux is undeniable.

Poststript: Moutier After Vénus

It appears that the Valjoux 7730, 7733, and 7740 were produced at the Vénus workshop in Moutier, though we can not be entirely certain. A 1974 news report says that the factory remained in operation and was even expanded in 1971. This likely refers to the former Pierce factory, where Vénus built a modern factory around this time. But the Swiss economic crisis of the 1970s deeply cut the profitability of all watches made in the country, even the popular chronographs, which had not yet been replaced by quartz.

It is likely that the Valjoux factory in Les Bioux handled production of Capt’s revolutionary automatic Cal. 7750 rather than the Vénus workshop in Moutier, and production of the older hand-winding chronograph movements there soon came to an end. Valjoux quickly ramped up production of Cal. 7750, with millions of examples produced between 1974 and 1977. But the Swiss franc continued to appreciate against the dollar and even the high-volume automatic chronograph lost its appeal. Production stopped entirely by 1978 as Swiss watch production collapsed and Valjoux was absorbed into Fabriques d’Ebauches Réunies (FER).

As mentioned, Moutier was also home to Pierce Watch Co., a “dissident” watch manufacturer that pioneered the vertical clutch chronograph when no member of Ebauches SA or ASUAG was allowed to trade with them. Originally called Léon Lévy Frères, Pierce occupied a factory complex near the center of town. Vénus had relocated to the rear buildings of the Pierce factory in 1960 and built a modern factory there in the late 1960s. The landmark front building was purchased by Ebauches SA around 1980. By this time, Vénus was a modest supplier of watch components to the watchmaking cartel.

The Moutier factory (along with those in Fleurier, Peseux, and Les Bioux) was merged into ETA of Grenchen in 1982. The tiny operation, with just 50 employees, was deemed unprofitable and ETA announced that it would be closed in March 1983. By that time, Ebauches SA was dissolved into ETA as well, and all attention was turned to the new Swatch watch.

Although Moutier was left out of watchmaking through the 1980s, momentum was building behind the various watchmakers in the entity now called Swatch Group. The resurgent ETA needed to expand movement production in 1992 and returned to the modern Vénus factory in Moutier, which they named Usine Les Golats. Eager to re-start production at the factory, the town even allowed ETA to operate the factory through the night, which Grenchen would not allow. The Moutier operation was so successful that the company expanded production of ebauches and movement components across the railroad tracks to another historic factory, now called Usine Graitery. Today, these are known as factories W16 and W15 and remain key production sites for ETA watch movements.

Images: ETA.ch

Vénus: The Grail of Chronographs

Paul Berret’s little watch movement company in Moutier was utterly transformed in just a decade: A maker of compact movements became the leading chronograph manufacturer under Ebauches SA, producing both the most-loved (Cal. 190) and most-influential (Cal. 188) movements in the field. And the legacy of Vénus lives on in both the 7750 automatic chronograph movement and the two ETA movement factories in Moutier. Given the success of Berret’s company, it is surprising to discover that it had very little history before being absorbed into the holding company and was able to carve out so much success despite being a small component in a much larger operation.

External Links

- I will definitely be visiting Musée du Tour when I am next in Switzerland, and I recommend that anyone interested in the history of Vénus and Moutier visit their wonderful website!

- You’ll find a lot more technical details on the Vénus movements over on Grail Watch Reference in the Vénus brand page. And of course Dr. Ranfft’s pink pages are invaluable!

- Information on the Moscow and Tianjin movements is scarce, but the following are doing the work to document them: Strela Watch, Kaminsky, Polmax3133

- Special thanks to my friend Fred Mandelbaum who provided timely assistance, especially with regard to Breitling watches.

- I would never have been able to do this research without my Primary Sources, notably the Rero Doc digital library and Europa Star digital archives.

Postscripts

There are a few more things that need explanation but don’t fit neatly into the narrative. I’m including those here.

Postscript: Schwarz Etienne’s Montres Venus

The brand name “Venus” was also used on complete watches throughout the 20th century, but these are unrelated to the movement maker, Fabrique d’Ébauches Vénus or Vénus SA. We see the Venus brand registered in La-Chaux-de-Fonds as early as 1902 by Paul Arthur Schwarz and Olga Etienne-Schwarz, a family name that is quite familiar to watch enthusiasts today: Schwarz-Etienne is a maker of high-end watch movements used by many brands, including Ming! The Vénus name was also used on radium dials produced in the 1920s and a luminous material company in the 1940s. None of these was related in any way with Fabrique d’Ébauches Vénus of Moutier.

Postscript: Vénus and the Pierce Factory

Image: La Fédération Horlogère, December 7, 1949

Léon Lévy Frères’ Pierce Watch Co. was fiercely independent, refusing to join Ebauches SA or ASUAG even after being “frozen out” from all watch component trade from the 1930s through the 1950s. But the company found its own success thanks to an inexpensive chronograph movement built entirely in-house in their landmark factory in Moutier. But Pierce suffered once the cartel loosened restrictions in 1958, allowing thousands of watchmakers to spring up all over Switzerland. The company abandoned its movements and adopted standard movements from A. Schild and other Ebauches SA members. Pierce had always listed Bienne/Biel as its headquarters. Although it proudly touted its Moutier factory through the 1940s, this was no longer part of the Pierce story in the 1960s. And in 1965 Pierce relocated from the historic “Rockhall” villa above Bienne to a modern office near the lake, suggesting that all production and assembly of watches was outsourced by this time.

Vénus responded to the strong demand for chronograph movements in the 1950s by purchasing the Pierce factory at Rue des Fleurs 17 and moving their operations there by 1960. As seen in the “help wanted” ad at left, Vénus was hiring a wide variety of technicians, mechanics, lathe operators, and workers at this address by June of 1960. It is likely that the company moved its operations entirely around this time.

The 1967 photo included in the article above shows the modern replacement for the historic Pierce buildings, which today has become ETA’s W16 “Usine Les Golats”. Given this date, we can assume that it was Vénus that built this new factory rather than Pierce or even Valjoux. The only question is when: The 50th anniversary article below suggests it was 1971, but the photo above was dated October 1967. Perhaps that date is in error?

Postscript: Vénus at 50

Image: l’Impartial, September 13, 1974

Although it is difficult to “prove” history, primary sources can sometimes be definitive. The folk tale that Vénus was acquired by Valjoux in 1967 (or 1966 or 1964) and promptly shut down completely is one example of this principle. Vénus definitely did not shut down in the 1960s, and in fact remained in operation in Moutier at least until 1982! Read on for the proof.

At right is an article from the Swiss newspaper l’Impartial dated September 13, 1974. It clearly and definitively establishes that Vénus was still in operation in Moutier at this time. And it definitively tells us that this is the original Vénus, founded by Paul Berret in 1924, attached to Ebauches SA in 1928, and still employing some of the same workers for over 30 years.

The article also includes a simple sentence that raises many questions: “En 1971 l’usine était encore agrandie” (“In 1971 the factory was further enlarged”). This clearly tells us that Vénus remained a viable enterprise into the 1970s and invested in the factory the company had used prior to this point (“further enlarged”). Since we know that Vénus used the Rue des Fleurs address since 1960, we imagine that this refers to that location rather than their original Rue du Midi address. But, as noted above, the replacement of the former Pierce factory is seen in a photo dated 1967, not 1971.

Postscript: What Was Vénus Manufacturing in the 1970s?

We can also infer that Vénus was worthy of investment by Ebauches SA in the 1970s. Since all Vénus-branded movements were cancelled and the tooling of Cal. 150 and Cal. 175 sold to Russia and China, one wonders what Vénus was producing in Moutier in the 1970s. The answer is quite plain: The Valjoux 7730, 7731, 7733 family, and 7740.

Cal. 7730 was essentially identical to Vénus’ Cal. 210 apart from the switch to a Valjoux-style mobile stud carrier. It entered production in 1966, immediately after the Vénus movement was cancelled. Given that movement manufacturing relies on specialized tooling, suppliers, and workers, it is logical to assume that Valjoux simply re-started production in the same location.

Cal. 7731 was launched soon after and had a new balance and balance cock. This suggests a change of vendors, since the assortment was typically outsourced. Still, it is likely that this too was produced in Moutier.

The movement was more-thoroughly redesigned in 1969 to become Cal. 7733, so production could have been moved to Valjoux in Les Bioux or shared between the two factories. This generation was joined by versions with calendar functions likely derived from the work of Dubois Dèpraz in the Vallée de Joux since it closely resembled the module they created for the ESA Mosaba Cal. 9210.

Next came the Valjoux Cal. 7740, which is also obviously derived from Vénus Cal. 210. Production of the Cal. 7730 series appears to have ended around 1974, while Cal. 7740 remained in production a little longer after the introduction of the automatic Cal. 7750, which was produced in the Les Bioux factory by Valjoux.

All of these movements appeared before the 1974 article posted above. It is not specific about which movements Vénus produced in Moutier, but also does not note that the company no longer produced any movement. The logical conclusion is that the factory was still producing hand-winding chronograph movements based on the classic Vénus cam switching design.

Postscript: The Closure of Vénus

Vénus remained in operation in Moutier much longer than modern folklore would suggest. It was not closed when the historic column wheel chronograph tooling was sold to factories in China just before it was merged into Valjoux within Ebauches SA, or when Valjoux was merged with Unitas, Peseux, and Fleurier to become Fabrique d’Ebauches Réunies (FER) in 1978. But Vénus was no longer producing watch movements at this point either, and was much reduced in size.

In the mid 1970s, the Poljot factory in Moscow purchased the tooling for Cal. 7734 from Ebauches SA, creating their Cal. 3133. This is the same company that purchased Cal. 150 in the 1950s, and it seems likely that this equipment also came from Vénus in Moutier. Polmax3133 claims the earliest production was 1975, so this would place the end of production of Cal. 7734 in Moutier around 1974.

By the time ETA took control of all of Ebauches SA in 1982, Vénus employed just 50 workers in Moutier and was reduced to being a maker of pinions and other watch components for other movement makers.

References

The history of Vénus is poorly documented, and this article summarizes a great deal of research. Considering the affection for their “golden age” chronograph movements, it is surprising that Paul Berret and the original Spozio factory are essentially forgotten. Even the connection between the cam switching Cal. 188 and today’s Cal. 7750 and Valgranges movements is usually overlooked. Hopefully this work will help shine new light on this important company.

The Development of Vénus SA

We have a great deal of definitive information on the founding and establishment of Vénus as well as the related companies of Kurt Henggeler-Gasser. But there is very little precise information on the date that Vénus became part of Ebauches SA or the circumstances of this transaction. The first mention of Vénus as a component of the cartel is March 1928, and we know that Sydney de Coulon joined the board of Vénus on August 16 of that year. But the acquisition itself was not covered in the Swiss newspapers.

In industry.

The factory of the Spozio brothers, if our information is correct, would be taken over very soon by new tenants who would intensify the watchmaking prosperity of our locality, we write from Moutier to the “Jura Journal”. No one will complain about this good news. Do we know that the morning and evening trains to Granges are full of workers who have to go to Granges to earn their daily bread? It would be greatly to be hoped that the native population could once again experience the good old days when local industry sufficed to occupy all the available labour.

50th anniversary of Venus SA

Today, Friday September 13, the Vénus SA factory in Moutier celebrates the 50th anniversary of its foundation. On this occasion the staff of some 170 people is invited to a race in the Neuchâtel region with a banquet followed by a recreational evening on Lake Biel.

The first director of the factory was Mr. Paul Berret and the Vénus factory was affiliated with Ebauches SA in 1928, a holding company which today employs some 10,000 people in some twenty watchmaking companies for the houses affiliated with Ebauches SA. In 1971 the factory was further extended. Among the staff there are some loyal collaborators who will be honored: Mr. Fritz Huber, director of the Männerchor of Moutier who has 38 years of service, Miss Henriette Jolissaint 37 years old, Mrs. Denise Jourdain 34 and Mrs. Hermance Sauser 33.

We wish all the staff a great day on this occasion.

Image: l’Impartial, September 13, 1974

Another blow to Moutier. The bar turning and watchmaking supplies company Venus SA, a subsidiary of ETA, is going to lay off 24 of the 50 workers it still currently employs. Of the remaining 26 people, 19 will be able to be employed in Granges, the others having to retire early. The company will close its doors at the end of March 1983. Such is the information obtained late yesterday afternoon.

The secretary of the FTMH of Moutier, Mr. Elia Candolfi, had an interview on Monday in Marin with the leaders of the group. He reacted strongly to the announcement of his measures, but could have had no influence on the decisions taken. The FTM will make every effort to provide assistance to those affected by these measures, in particular by focusing on the social problems they cause. Most of the people made redundant are bar turners and specialized workers.

This company, which under the name of Pierce had employed 200 to 250 people, was taken over by Ebauches SA in 1980. It became a subsidiary of ETA, in Granges. At that time formal promises of development had been given by ETA. Then we witnessed transfers, dismissals.

Venus SA occupies a modern building that is around ten years old. As for the Herman Konrad company, which was also recently closed, we do not see who could be interested in this factory. The announcement of these layoffs and this factory closure is a new blow to the economy of the city where unemployment is rampant.

Image: FAN l’Express November 25, 1982

The People of Vénus: Paul Berret

Moutier

l’Impartial, November 26, 1949

Death of Mr. Paul Berret

Mr. Paul Berret, director of the Vénus ebauche factory, who died at the age of 61, was well known in Moutier and Delémont, as well as throughout the region.

The deceased was born in Cornol but it was in Delémont, where his father had a wine business, that he spent his childhood and studied. From a pleasant approach, Paul Berret hid under an appearance of carelessness a serious nature and a tenacious will. After his technical studies, Mr. Berret went into practice and became technical manager at the large Schild S. A. factory in Granges. In 1924, on May 1, he came to Moutier, where he took over the factory of Mr. Victor Spozio and set up a blank factory there; this one was absorbed by Ebauches S. A. and Paul Berret retained its management. He knew how to make himself appreciated by his staff with whom he celebrated last year the 25th anniversary of the founding of the firm.

Mr. Berret took a keen interest in several local societies and particularly in the Municipal Fanfare of which he was the active president for many years; he was also an active member of the Alpine Club. Paul Berret leaves the memory of a friendly man who was unanimously loved and respected. We send our sincere condolences to the bereaved families.

Leave a Reply