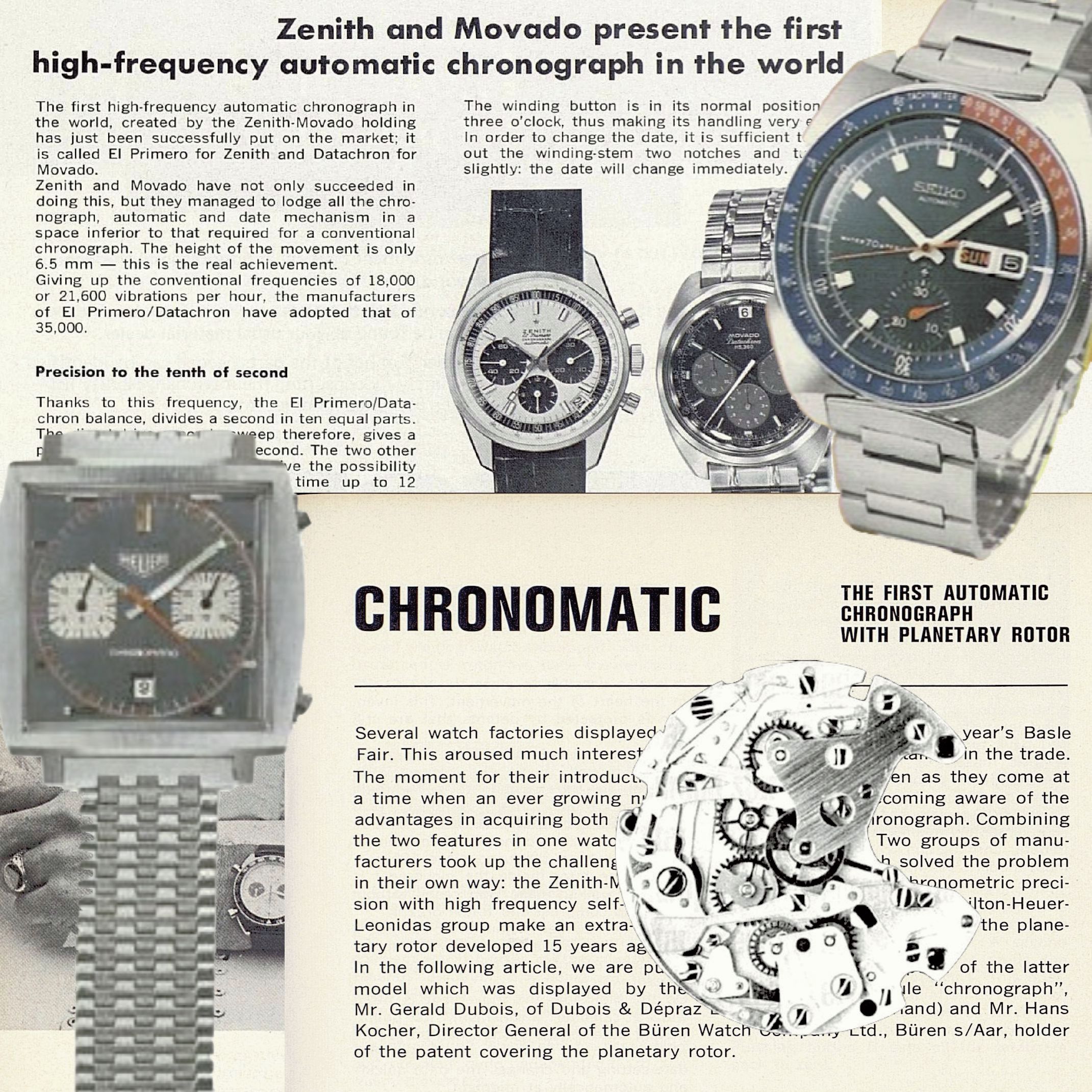

In an industry as full of folklore and puffery as watchmaking, it is refreshing to uncover first-hand knowledge. As I was researching the history of Zénith, Universal, and the Martel watch factory I stumbled on a real gold mine: A 1991 interview with Charles Vermot, the watchmaker who saved the legendary El Primero watch movement from the scrap heap. In this incredible video, Vermot describes the impact of the quartz crisis and Zenith’s decision to stop production of mechanical watches. It’s just as interesting to hear the commentary on the watch industry in that era, just five years removed from the lowest point in the history of Swiss mechanical watchmaking!

The video continues with a look at how the watchmaking profession was viewed in 1991, as the industry was just recovering. A group of students in Le Locle are uninterested in entering the profession, while their parents admit that they didn’t push it at home. But students at the watchmaking school in Le Sentier seem primed for bigger things, even if there aren’t enough of them. And the older workers at the houses of Blancpain and Audemars Piguet express their love for the work, even as they admit the long hours and poor pay. We even get a look at the women making hairsprings at Nivarox-FAR!

Because my audience is predominately English speaking, I decided to translate the commentary from the video. I encourage you to watch the original RTS broadcast, however, and to savor the opportunity to hear history in the words of those involved.

Source: RTS.ch – “Le retour du tic tac,” June 21, 1991

Charles Vermot Tells the El Primero Story

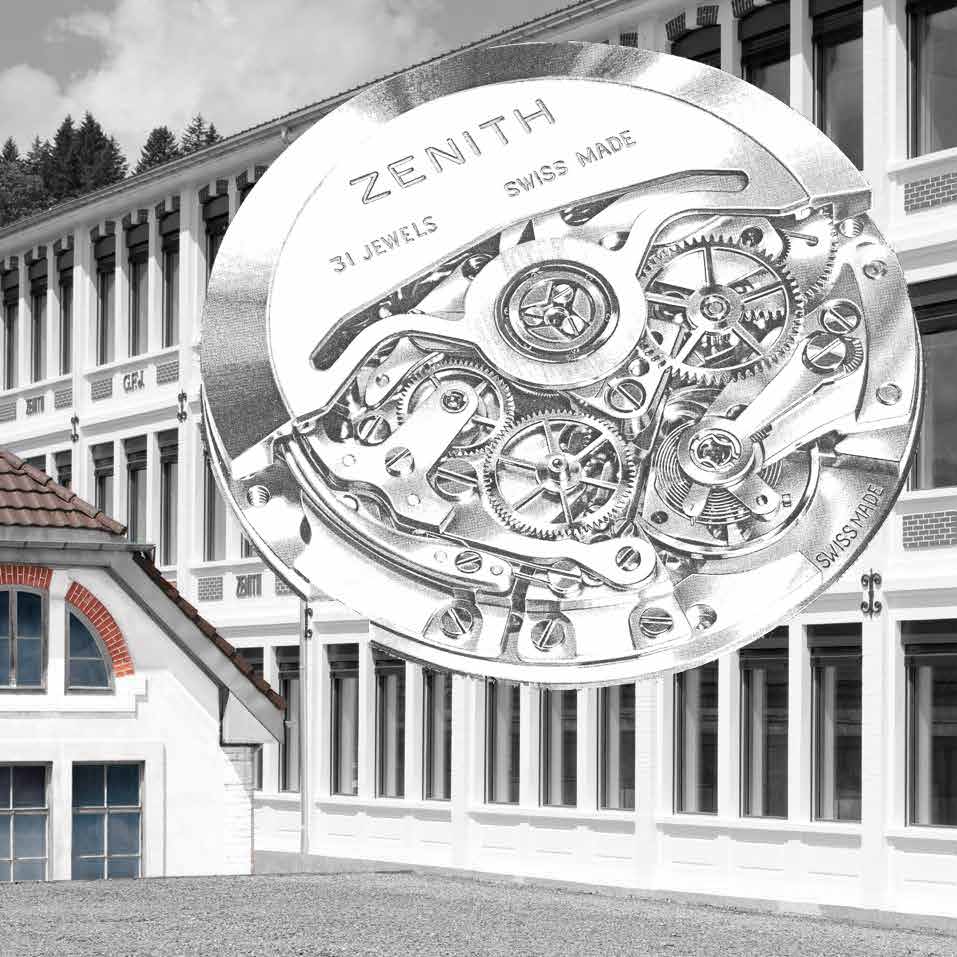

This interview with Charles Vermot confirms the key details of the history of the Zénith El Primero, including how he saved the tooling in the 1970s and re-started production in the 1980s. But a closer listen reveals more critical details:

- Vermot confirms that the El Primero movement was produced at the Martel Watch Co. factory in Ponts-de-Martel, not the main Zénith factory in Le Locle. He is very clear on this point, discussing how it felt to be “among the bogs” in Martel and separate from the headquarters, out of sight and mind for the American Zenith corporation.

- Production manager Jean-Pierre Gerber reiterates that the company would not have been able to reproduce the complicated El Primero movement without Vermot’s careful preservation of the tooling, since it would have cost 6 or 7 million francs to do so. This helps explain why so many companies (notably Ebel and Rolex) chose this particular movement.

- Another amusing anecdote is Vermot’s payment for his secret act: An El Primero watch (which he wears while gardening) and a nice dinner with his wife!

- It’s also nice to hear the name of Paul Castella included in the story. The manager of the Dixi machine tools company in Le Locle, he purchased many of the town’s watchmakers when they faced difficulty. Without him, Zénith, Movado, and Zodiac might not have survived. But he did not live to see H. Moser & Cie. resurrected, and Paul Buhré and Robert Cart have not been revived.

Learn more about the context of this video by reading my article on The Fall and Rise of Zenith, 1969-1988.

Transcript

Daniel Pasche: “Good evening. The mechanical watch. A few years ago, one would have thought it was dead, finished, outdated. It was the time when the electronic watch flooded the market with its silence and precision. A wave that led many factories to bet everything on Quartz, and too bad for the formidable know-how accumulated by watchmakers who pass on their art from father to son. However, things are slowly changing, even if we can’t talk about a tidal wave, the mechanical watch, the good old ticking watch, is coming back. It may be a little less precise than Quartz, but it has a soul, it has a history, and above all, it has personality. In a word, it’s not just anyone’s watch; today, it represents 42% of our exports in value. But this return, as you will see, poses problems of labor and training. It would not have been possible if two old and obstinate workers, almost against the will of their boss, had not known how to preserve their work instruments. This is what Liliane Roskopf and Jean Rigataux discovered for such a case.”

Liliane Roskopf: “In the 1970s, watchmaking was in crisis. The culprit was the Quartz, 30,000 oscillations per second, unbeatable precision. It almost killed the traditional watch. However, since 1988, defying all predictions, the mechanical watch is making a comeback. It is more expensive and less precise than Quartz, but it ticks, this irreplaceable sound.”

Charles-André Piguet (watchmaker): “The mechanical watch is noticeable because of the turning balance wheel. In other words, on the front page, it’s all ethereal. Everything is closed.”

Charles Vermot: “Electronics are abstract. You open an electronic watch, I have nothing against progress, noting the electronic precision, it’s magnificent. And you will have another electronic device with wires and solder points.”

Ariste Gueniat (watchmaker): “A mechanical watch is a watch that you live with, it’s not the same thing; you can leave it for 5 or 6 months in a drawer and then pick it up. A mechanical watch works again if you don’t wind it after 40 hours, and it stops.”

Liliane Roskopf: “Fifteen years ago, no one would have bet a penny on the future of mechanical watches. Today, they are in high demand; the more expensive and complicated they are, the more we love them, even if we have to wait a long time for them, up to 3 years, for certain models’ delivery time. Mechanical watches represent almost half of our exports; it’s a resurrection. Like any resurrection, this one is a miracle. Some manufacturers almost failed to rediscover their ancestral technique, for example, Zenith in Le Locle, a house over a hundred years old. In 1972, the firm was sold to Americans who decided to completely switch to Quartz and get rid of the precious mechanical production tools. For Zenith, the miracle has the face of this retiree, employed for 40 years as the head of blank production. He passionately loved his job, watches, and especially this automatic chronograph. A creation in 1969, baptized El Primero.”

Charles Vermot: “I was given permission to stop making the more mature wing altogether.”

Liliane Roskopf: “What was your reaction?”

Charles Vermot: “Finally, it came as a shock.”

Liliane Roskopf: “You thought that’s why they wanted you to stop this production.”

Charles Vermot: “Being under American management, it was the electronics that counted, the quartz watch, and there was no longer any chance for the chronograph.”

Liliane Roskopf: “But you were convinced at the time that it was a mistake to quit.”

Charles Vermot: “Ah, they would have cut off my head if I had said that. I was sure that one day or another, the chronograph, yeah. To restart, to start.”

Liliane Roskopf: “Mr. Vermot is so sure of himself that he wrote to the management, asking that a small workshop be maintained where the tools of El Primero would be put on hold and carefully preserved.”

Charles Vermot: “Without discounting progress, I note that the world is like this; there are always backtracks. You are wrong to believe in the total stoppage of the automatic mechanical chronograph as well. I am convinced that one day your company will be able to benefit from the fads and fashions that the world has always known.”

Liliane Roskopf: “The factory of ebauches in Ponts-de-Martel was liquidated, and the building was taken over by a food company.”

Liliane Roskopf: “What did you do with this material? This tooling?”

Charles Vermot: “Well, at first, from here, from Ponts-de-Martel, we labeled everything. So we packed everything that is, like everything that is. Being all the cutting tools, small machines. That would have been thrown away, so I asked the management to let me take care of everything that had been labeled; it’s still these cutting tools from Ponts-de-Martel, even files, operation plans, range of operation, and so on, to be able to put everything in one, in the same room. What was denied to me, denied. I was not as widespread. I was feeling a little apart from Ponts-de-Martel. It was a bit in these bogs; it was necessary to wake up and realize that we were in the electronic age.”

Liliane Roskopf: “The equipment risks being sold or thrown away. Mr. Vermot is afraid; he hides this equipment in the hidden corner of the company. When your colleagues see you hiding the equipment, putting it away, what was he saying?”

Charles Vermot: “Well, I’ll tell you one thing, with my close colleagues, several said to me, ‘But listen, come on, get over it. You’re making us laugh with your automatic mechanical chronograph. We’re in the electronic age, but what do you want to achieve?’ But that time, it’s outdated.’ I said, ‘No, I don’t believe that. It will cost a few months of training. We can find more than that; I am almost certain that the company will need it later.'”

Liliane Roskopf: “Mr. Vermot remains unshaken in his idea, alone against everyone. For nearly 10 years, his treasure sleeps on shelves where no one ever comes. One component is worth 40,000 francs, and 150 are needed to manufacture the chronograph. One fine day in 1984, an engineer aware of the rescue came to announce the news.”

Charles Vermot: “So there, as this was near Vermont, he asked if we could, together, find, he can take out all the tools, see the possibility of restarting. So I said just now with pleasure.”

Liliane Roskopf: “You were there, then?”

Charles Vermot: “Yes, there, I have been there anyway. Yes, there, I was, what’s his name?”

Liliane Roskopf: “Your dream came true.”

Charles Vermot: “Absolutely.”

Liliane Roskopf: “A dream supported by solid work. Not content with having organized and labeled the tools, the meticulous production manager recorded all the useful indications for their revival in a file. And the new management rewarded you.”

Charles Vermot: “Yes, absolutely. With this beautiful piece that gives immense pleasure.”

Liliane Roskopf: “It is the El Primero.”

Charles Vermot: “And then, with my wife, we were invited to a good meal.”

Liliane Roskopf: “So it was a nice surprise found by the new management, namely Paul Castella, who took over Zenith in 1978. All the parts have found their place. The production of the chronograph resumed. Today, it is the flagship product of the company.”

Jean-Pierre Gerber: “It is almost certain that if all the tools that were archived and cataloged by Mr. Vermot had disappeared, the decision would have been negative.”

Liliane Roskopf: “And why? Because you wouldn’t have remade these tools?

Jean-Pierre Gerber: “Indeed, we could have remade them. But there were two essential conditions. On the one hand, it was the time needed to remake all the production tools, which would have taken several years, and on the other hand, a considerable financial investment (6 to 7 million francs). Very close to that, that’s it.”

There’s actually a newer cut of this interview featuring Charles Vermot’s son Michel Vermot! Watch that version below. Sadly I did not know about that before translating this older one!

A Perspective on Watchmaking in 1991

After the segment with Vermot, the story continues with a look at the attitudes of watchmakers and young people toward the profession. This part is equally fascinating, since it reflects the questions many had about the revival of mechanical watchmaking in 1991. It’s important to recognize that this business was effectively at an end just 10 years earlier, with the revival of mechanical watches, especially complicated ones, not really under way until the second half of the 1980s.

A few notes:

- Watchmakers were not well-paid at the time compared to other professions, and many women worked in the trade. This continues today, with many watchmakers coming to Switzerland from other countries for training and work.

- We get a look inside the Zenith factory in 1991. Although dated, it is much more modern and industrial than the others we see later in the program.

- We also see the inside of Nivarox-FAR, perhaps the most critical element of Swiss watchmaking since without their springs there could be no more mechanical watches. I have recently written about the Balance Spring Cartel Crisis and will soon publish much more about this key component!

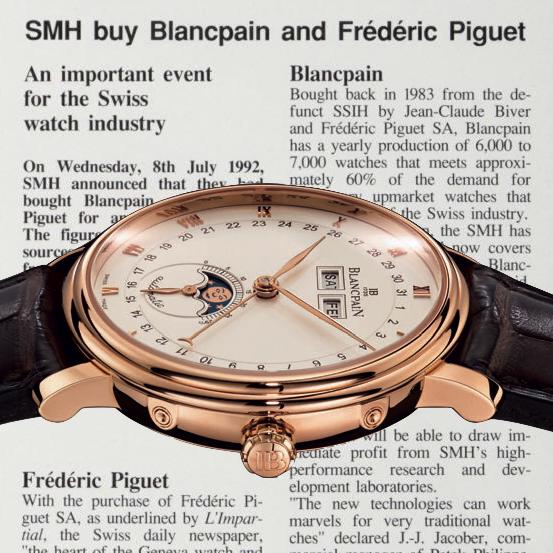

- It’s also interesting to see just how primitive the Blancpain and Audemars Piguet workshops were back then. Both are much more impressive today!

Learn more about Blancpain by reading my article, Blancpain, F. Piguet, Biver, and the Path Forward

Transcript

Liliane Roskopf: “Another problem related to the return of mechanical movements is the lack of watchmakers. The Quartz has been harmful to the profession, not only because of unemployment but also because assembling an electronic watch does not require as much expertise as assembling a mechanical watch.”

Denis Stein: “We are looking for complete watchmakers.”

Liliane Roskopf: “And for example, in this company, how many are you missing?”

Denis Stein: “Well, you have an extra workload. And then we are forced to train people with a basic watchmaking background. We train them within our factory, but it requires some time.”

Liliane Roskopf: “The employers’ circles launched an intensive campaign of advertisements in local newspapers and radios as early as 1980, broadcasting slogans every hour praising the watchmaking professions. These job offers focus on the creative and prestigious aspect of the profession. But young people do not respond as massively as employers would like. In their eyes, watchmaking has drawbacks; it is subject to recurrent crises. There is no guarantee that the current enthusiasm for mechanical watches will last long. Moreover, it is a secondary sector, meaning that the work is often repetitive and not very well paid. After 15 years of practice in the canton of Neuchâtel, a watchmaker earns 4500 francs per month. Would you consider pursuing a career in watchmaking?”

Girl: “Not at all.”

Liliane Roskopf: “Why is it not interesting to you?”

Girl: “No, because we are always in the factory, always doing the same thing, always in the same office. I’m really looking for something else.”

Liliane Roskopf: “Don’t you think that with the return of mechanical watches, there is more variety?”

Boy: “Yeah, but the job is still the same. It never changes. It’s always the same.”

Boy: “I don’t want to do the same thing as me, you know.”

Liliane Roskopf: “Nivarox in Saint-Imier is the only company that produces what is called the heart of the watch, the escapement, balance wheel, and spiral. All watch manufacturers in the country depend on them. The key figures of this work, the watchmakers, are facing a shortage that becomes problematic. While the workshop is full, these young women have received only partial training. There are only five true watchmakers left. The apprenticeship was abolished in 1967 with the appearance of quartz. These five women, with the exception of one, are over 55 years old and have a particularly meticulous and challenging job. How old are you?”

Marie-José Perret: “45 years old.”

Liliane Roskopf: “Is this a profession you would recommend to a young girl?”

Marie-José Perret: Well, I could recommend it willingly, but let’s say that, for example, I have daughters. They wouldn’t want to do what I do, you know. Because you always have to be at the workbench with the microscope, and you have to be careful; you can’t use too much force. It’s very delicate. It’s true that in watchmaking, there are ups and downs. But for now, let’s say we’re back on track, but we never thought about it, because 10 years ago, whenever they asked me what I did, I just said I worked in a factory. We didn’t know what some things were. We said yes, but that is over now.”

Liliane Roskopf: “If there is a place where the watchmaking profession is fully artisanal, where particularly refined and complicated mechanisms are produced, it’s the Vallée de Joux. Therefore, the students at the technical school in Le Sentier, the most important of the 7 watchmaking schools in Switzerland, consider their profession with two solid motivations and without worry because they are already. Even before finishing their studies. Many young people fear the industrial aspect of the watchmaking profession, but not in your case.”

Michel Capt: “No, not in my case, let’s say. I think that with the training we can get in a school like this, the future lies in complex pieces and non-repetitive work. We don’t have large-scale production.”

Liliane Roskopf: “How did you find your place? Were you recruited here at the school?”

Michel Capt: “Yes, they came during the open days, and then we had a discussion. Let’s say that it turned out that I was presented there, and I visited, and then I really enjoyed it. All the employers come to the school to offer contracts to your apprentices. In general, they are looking for apprentices. So, you just have to choose.”

Liliane Roskopf: “However, the technical school only trains six apprentices per year, and the valley has 12 manufacturers. So, there are still empty spots in the workshops.”

Régis Meylan: “Those who graduate from the school may not necessarily have the experience of a national watchmaker with 15 or 20 years of experience. Young people are needed, but they need to be patient to truly work on more complicated watches.”

Liliane Roskopf: “It may seem surprising that a region that has always excelled in high-end mechanical watchmaking is facing a shortage of watchmakers. The reason is simple; orders have multiplied in recent years. The consequence is that customers have to wait for their pieces for months or even years. For now, the know-how in the valley relies on a handful of master watchmakers with 50, 60, or more years of experience. These watchmakers are the ones who manufacture watches known as “grand complications.” These watches truly live up to their name. They consist of over 400 different pieces and add to their basic functions, features such as a perpetual calendar programmed until 2100, moon phases, striking, and minute repeater. To complete one of these watches, a watchmaker needs to be an expert. Even a company that is starting anew, like Blancpain, which almost disappeared during the Quartz era, needs to hire experienced and relatively older personnel. The company takes pride in having always produced mechanical watches, and this superb tradition is mainly supported by two watchmakers who are close to retirement. What piece are you working on right now?”

Charles-André Piguet: “A minute repeater watch. This one is worth about 92,000 francs.”

Liliane Roskopf: “Are you impressed or do you get nervous when you work on it?”

Charles-André Piguet: “Never. When you work, you should not be stressed or tense. If you are, it’s better to take a walk outside and come back 10 minutes later.”

Liliane Roskopf: “Do you think you’ll retire?”

Charles-André Piguet: “I hope so, but if we can’t find anyone to replace me, we’ll have to continue. Because in reality, I’m the only one here who can do everything and oversee everything.”

Liliane Roskopf: “Yes, so you train young people?”

Charles-André Piguet: “Yes, I do, but it takes them 8 to 10 years to learn everything, maybe even more. So, you’re not close to retirement. It seems not.”

Liliane Roskopf: “But I imagine that you are indispensable since you make high-priced watches. You must have been offered a fortune to stay here.”

Charles-André Piguet: “You know, at the beginning, they always try, but not a fortune. That’s not always the case. No, the salaries are quite normal. We can say they are similar to those here.”

Liliane Roskopf: “Can you say how much?”

Charles-André Piguet: “Oh, I can tell you. It’s more than 6000, that’s for sure.”

Liliane Roskopf: “Adding that it’s not just the salary but also the working hours, as they often work 10 hours a day, they need to produce watches and train the next generation. Tell me, if you suddenly stop working, what would happen to the Blancpain Company?”

Charles-André Piguet: “Well, it’s difficult to say. The young people I have here are talented; they manage to keep up. But I think there would be a decline for a while.”

Liliane Roskopf: “Same passion, same responsibility, and same hours for seven other watchmakers. How old are you?”

Ariste Gueniat: “Well, on December 26, I’ll be 65.”

Liliane Roskopf: “Will you retire?”

Ariste Gueniat: “A very pertinent question. But I don’t think so. There’s still quite a bit of work to finish. We’ve discussed it before. I think I won’t retire.”

Liliane Roskopf: “Yes, for the company, you can’t hand it over?”

Ariste Gueniat: “No, not at all. That’s it.”

Liliane Roskopf: “At Audemars Piguet, they create the most prestigious pieces in a 19th-century restored workshop. The Americans love them.”

The Grail Watch Perspective

This simple video is a gold mine for historians seeking to understand the re-birth of watchmaking. It is truly magical to hear the story of the El Primero direct from Charles Vermot, and to confirm some aspects of the Zénith-Martel mystery. But it is also incredible to glimpse the true state of watchmaking in the early 1990s as the industry was returning from the brink. I wonder what happened to the people featured here – the student Michel Capt, the charming spring maker Marie-José Perret, the old watchmakers Charles-André Piguet and Ariste Gueniat, and the rest. And it is incredible to contrast the modern Zenith, Audemars Piguet, and Blancpain to the cramped yet charming past.

I think your articles are very interesting and well researched