Blancpain is billed as “the world’s oldest watch company”, but the history of the company is far more complex. Founded before 1735 in Villeret, the modern Blancpain traces its heritage to 1981, when Jean-Claude Biver purchased the name to be a mechanical rebuke of quartz watches. Blancpain and movement specialist Frédéric Piguet would be acquired by what is now the Swatch Group in 1992, with Biver leading the renaissance of mechanical watchmaking.

This article accompanies Episode 4 of The Watch Files, a podcast from Europa Star and Grail Watch. Listen to “04 Blancpain, Biver, Piguet, and the Path Forward” and subscribe now!

The Blancpain Family in Villeret

In 1735, in the small village of Villeret in the Canton of Bern in the Swiss Jura, 42 year old Jehan-Jacques Blancpain, formerly a farmer, recorded his profession as “watchmaker.” This is significant, because it marks the official start of “the world’s oldest watch company,” though he was likely making watches even before this date. This same small town, located in the famed Jura Triangle, was the birthplace in 1721 of Pierre Jaquet-Droz, who would find fame for his automatons and had been industrializing at that time using water power from the Suze river, and would later see the incorporation of Minerva. Like nearby Saint-Imier, home of Longines, this industrial activity attracted new residents and drew workers from the fields to the factory.

It was not considered proper to sign one’s name to a watch at the time, so little is known of these early watches. Jehan-Jacques Blancpain’s grandson, David-Louis Blancpain, was known to have traveled throughout Europe selling the family’s watches, but the Napoleonic wars, and annexation of the region by France, caused havoc for watchmaking. Frédéric-Louis Blancpain, returning from military service, re-established watchmaking, developing a cylindrical escapement and focusing on ultra-flat movements for high-end pocket watches. In 1830, with his health failing, he turned the business to his son, Frédéric-Emile Blancpain who rapidly expanded the business. The firm focused on small watches designed for women, and began producing lever escapements. But he resisted the trend towards specialization, instead having a single watchmaker see a single watch through from start to finish.

The business was re-incorporated in 1865 by two of his three sons. As the Swiss industry suffered from over-production and American competition in the latter half of the 19th century, Blancpain endured thanks to its focus on high-end lever escapement watches. The scion of the next generation, also named Frédéric-Emile Blancpain, would oversee mechanization at long last at the turn of the century. Relocating to Lausanne, he sent home wax recordings of his notes to direct the factory, now under the management of Betty Fiechter.

Many know of the influential British engineer John Harwood, widely credited with inventing automatic winding watches. Noting that many watches during World War I failed due to water or debris infiltrating the case at the winding stem, Harwood was inspired by seeing children play on a see-saw to create an internal winding mechanism. Harwood worked with Blancpain to develop a working prototype of his self-winding watch, with an oscillating “hammer” at one end, based on his 1923 patent.

Harwood later contracted with A. Schild SA to produce his movements, and Fortis became well known as the producer of many of them. But Blancpain also licensed Harwood’s designs, and many feature the Villeret brand on the dial. Harwood’s watches lacked a crown entirely, using the bezel for hand winding and setting the hands.

In the 1930s, Frédéric-Emile’s Blancpain produced another automatic winding watch. The Rolls, designed for women, placed ball bearing rollers alongside the movement. A the movement slid back and forth inside the case, winding the mainspring, a similar concept to the automatic version of today’s Corum Golden Bridge!

See this deconstruction of the Blancpain Rolls from The Naked Watchmaker

Rayville-Blancpain

The firm had lasted in the Blancpain family through seven generations until 1932, when Frédéric-Emile Blancpain died at the age of 69. He had no male heirs, so factory manager Betty Fiechter and sales director André Leal purchased the firm. Because Swiss law did not allow an eponymous company to be owned outside the family, they renamed it in a novel way: The two syllables of their home town of Villeret were reversed, giving Rayville. Thus, Rayville SA produced watches bearing the Blancpain name for over forty more years.

Rayville rose as a producer of compact movements for other makers in the first half of the 20th century. In the American market, many small models from Gruen, Elgin, and Hamilton used Blancpain ebauches imported from Villeret.

The ultimate Blancpain movement from this period was the so-called Ladybird, introduced in 1956. Measuring just 5 ligne (11.85 mm) in diameter, it was the smallest round movement produced and enabled Blancpain to develop unique jewelry watches. This movement defined the design trends for the company for two decades and is a cornerstone of the company. A new “Ladybird” automatic movement was introduced in 1996.

In the 1950s, Blancpain also developed an ultra-thin movement, the Golden Profile, which enabled the company to compete in this hot segment. Another novelty was the 1959 automatic known as the Cyclotron with 53 functional jewels! It featured a pie-pan dial reminiscent of Omega and reflected the fascination at that time with automatic winding and high jewel counts. It certainly put Roamer’s 44-jewel Rotopower to shame!

Today, one of Blancpain’s most famous models is the Fifty Fathoms. Although often credited as the world’s first diving watch (it was introduced in 1953), it was mostly overlooked at the time: The first editorial mention of the Fifty Fathoms in Europa Star did not occur until 1971! Perhaps Rayville was more proud of their high-end watches, including one that won the Geneva Prize for “Bijouterie” that same year, than of this pedestrian tool watch. Still, the Fifty Fathoms left a mark on history, and Blancpain’s patent on the uni-directional bezel meant that Rolex, Breitling, and EPSA couldn’t include this feature.

Image: Europa Star 70, 1971

The Decline of Rayville in the SSIH

Although Blancpain’s production and profile had grown, it was an early victim of the industry-wide consolidation of the 1960s. The company joined the powerful Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogére SA (SSIH) in 1961, which also contained Omega, Tissot, and Lemania. At first, things went well for Rayville: Production expanded dramatically, with the larger brands relying of Blancpain’s compact movements. Indeed, production peaked at over 220,000 in 1971! But when the SSIH consolidated from a holding company into a single firm in 1968, Blancpain became just another brand as the Rayville movement factory was more prized

Still, the SSIH provided Blancpain the resources to grow as a producer of high-end watches. In the early 1970s, it was a rival for watchmakers like Audemars Piguet and Piaget and high-end jewelers like Bucherer, Gübelin, and Chaumet. Indeed, perhaps it was this competition which drove the Chaumet brothers to re-establish the historic Breguet brand in this period!

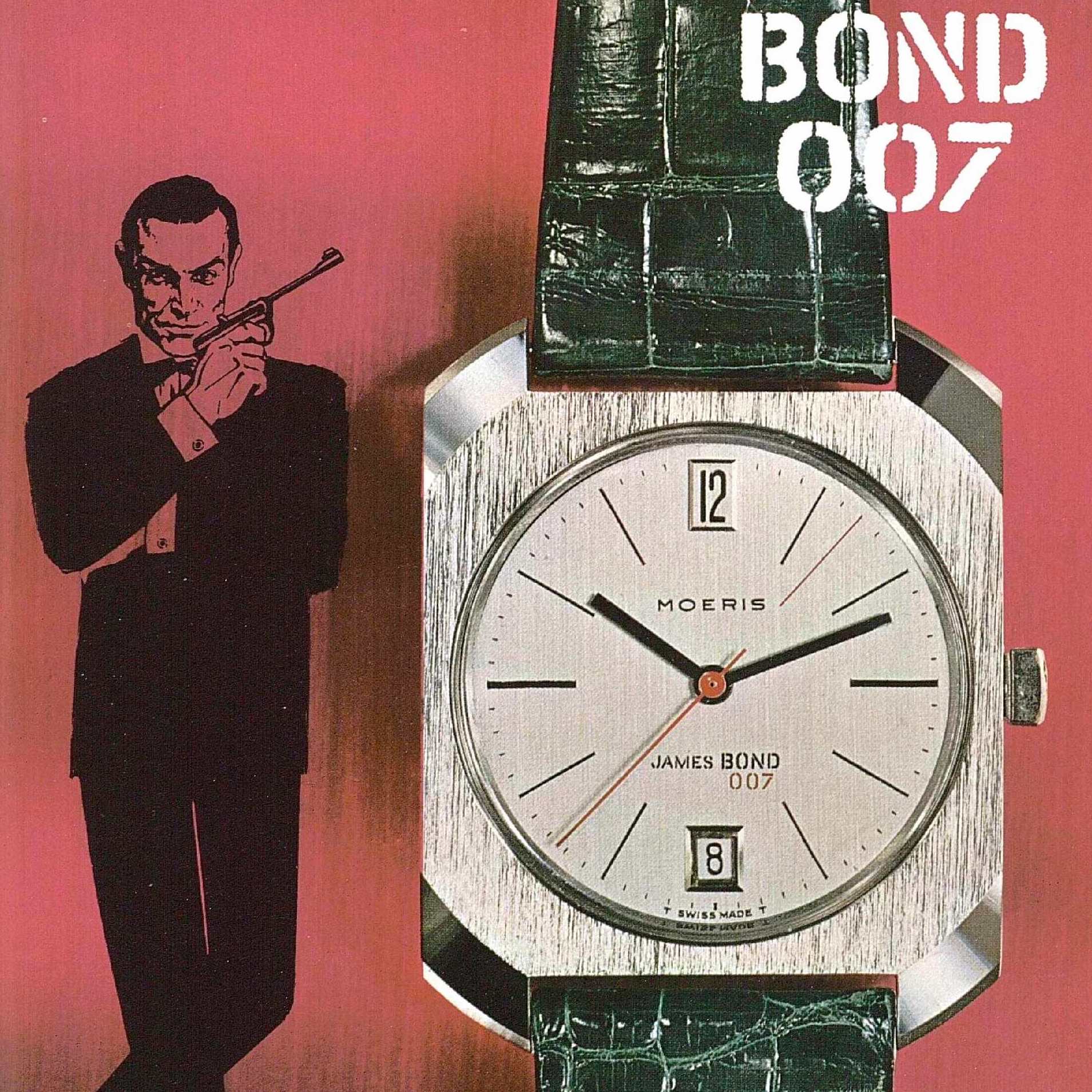

But the Blancpain brand quickly fell out of fashion in the 1970s. It had become Omega’s sister brand for jewelry, akin to Tissot on the low end. The Saint-Imier firm Moeris was purchased in 1974 and paired with Blancpain as a producer of historic and skeletonized pocket watches. That company was formerly a mass-market brand and has the distinction of producing the first “James Bond watch”! But this proved a poor pairing later in the decade.

Amid the drive to develop quartz movements, these brand name were set aside. Blancpain’s final appearance at the Basel Fair was 1975, listed as “Rayville Blancpain, Villeret”. They occupied a small booth opposite Omega’s pavilion, sharing space with mechanical chronograph maker Lemania. Rayville had become mostly a movement maker too, and Blancpain watches disappeared the following year. With Blancpain retired and Moeris moved under Tissot in 1980, Rayville also ceased to be a separate entity. The Rayville/Lemania booth at the 1980 Basel Fair was the last appearance of the original firm. Blancpain was defunct, and the company’s archives, designs, and tooling was destroyed. The Villeret factory was repurposed for production of Omega watches.

Blancpain and Frédéric Piguet

With Japanese quartz watches on the rise, the Swiss industry was in crisis. As Ebauches SA and ETA developed competitive quartz movements, the SSIH was shedding brands. Omega was doing well enough, but Tissot was near bankruptcy, and brands and factories were rapidly closed. Nicolas Hayek was brought in to reform the group in 1980, but his aggressive moves did not appeal to everyone. After Omega boss Fritz Ammann resigned, most of his staff left as well.

Read the story in the words of Jean-Claude Biver in this 2019 Europa Star interview

Among those leaving Omega was Jean-Claude Biver. He was in charge of the brand’s high-end gold watch lines and believe that the future of the industry lay in high-end mechanical watches like those from Blancpain and Lemania, not ultra-thin quartz. But Hayek slashed these entities from the company. Biver had befriended Jacques Piguet, and learned that his family firm, Frédéric Piguet, would soon be forced to lay off watchmakers as they too switched to quartz. Biver proposed an alternative solution: Launch a high-end mechanical watch company to absorb the excess production.

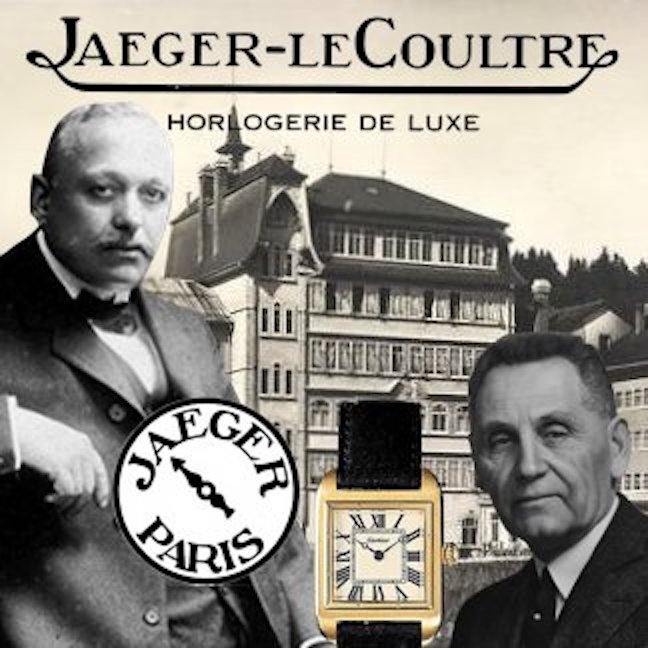

In 1981, Biver and Piguet purchased the Blancpain brand from SSIH for just CHF 21,500. They set up the brand in a Le Brassus farmhouse near the Frédéric Piguet workshop. This was an entirely new company, with no connection to the original apart from the name. Even the location was new: Le Brassus is in the Canton of Vaud, home of Audemars Piguet and Jaeger-LeCoultre and over 100 km from Villeret.

“Since 1735 there has never been a quartz Blancpain. And there never will be”

Jean-Claude Biver’s guiding words for the new Blancpain

The first new Blancpain watches appeared soon after, with one appearing in Europa Star in 1983. Combining the best of Frédéric Piguet movement technology with a classic design, the watch included a full calendar and moon phase. The design was classic yet up to date, and the complicated design could not be replicated using the quartz movements of the day. The design was based on a classic Frédéric Piguet movement from the 1940s, long out of production, and was revived by watchmaker Edmond Capt, famous for designing the Valjoux 7750.

The simple design remains an icon for Blancpain, and was one of the “six masterpieces” from the brand that exemplified “the living museum of the past” concept championed by Biver. Blancpain would build six key mechanical watches over the next decade: An ultra-thin watch, the moon phase display, a perpetual calendar, a split-seconds chronograph, a tourbillon, and a minute repeater.

At the same time, Günter Blümlein was re-launching high-end mechanical watches with Jaeger-LeCoultre and IWC, Gérald Genta challenged the industry’s conventions, Gerd-Rüdiger Lang founded Chronoswiss, and watchmakers like Svend Andersen, Franck Muller, Vincent Calabrese, and François-Paul Journe were on the rise. They all shared a vision of a resurgence of demand for high-end mechanical timepieces. And they were right.

A second line of Blancpain watches was established, and it was perhaps even more important. Launched at BASEL 86 was minute repeater and perpetual calendar with automatic winding, it exemplified the connection between the firms of Blancpain and Frédéric Piguet: Louis Elisée Piguet, founder of the Le Brassus movement specialist, is considered the originator of the perpetual calendar complication in wristwatches. He was also famous for his Grande Sonnerie and “Le Merveilleuse” grande complication watches of the 19th century. The movement, designed by Edmond Capt, was the smallest minute repeater produced to date.

At BASEL 88, Blancpain showed its first chronograph: This remarkable watch included not just a flyback chronograph complication and automatic winding (the first such movement developed in over a decade) but was remarkably thin just 6.75 mm overall. It was based on the F. Piguet Cal. 1185, which had been introduced in 1987 as the hand-winding Cal. 1180. This movement would be used by Audemars Piguet, Cartier, Chopard, Vacheron Constantin, and many others, and represented the future of the industry. Although it might seem surprising today, only “Nouvelle” Lemania, Valjoux (part of ETA), and Zenith produced mechanical chronograph movements at the time, and none were very modern. Frédéric Piguet would compete with Zenith’s re-launched El Primero and would draw away many high-end brands. The movement remains in production and use to this day!

Image: Europa Star 185, 1991

The final masterpiece of Biver’s vision was realized with the creation of a tourbillon wristwatch. After Audemars Piguet created the world’s first production tourbillon wristwatch in 1986, Frédéric Piguet began developing their own such movement based on a design by noted independent watchmaker Vincent Calabrese. They contributed to the 1989 minute repeater from Gérald Genta (who used other F. Piguet movements) and appeared again in 1990 in a special release for Asprey’s of London. By 1991, Blancpain released their own tourbillon wristwatch, a simpler model with an indicator showing a full eight days of power reserve. The novel tourbillon was visible at 12:00 in an open heart dial. As seen in the illustration at right, the Blancpain tourbillon was much larger than the tiny Audemars Piguet device, and looks quite different from modern models. This is due to Calabrese’s concept, which was somewhat related to his linear Golden Bridge movement.

Note that some sources quote a date of 1989 for the Blancpain tourbillon but I could find no contemporary coverage from that year, which is surprising since this would have been a massively-important announcement!

F. Piguet poured resources into the development of advanced mechanical movements as well as another key movement: The “Meca-Quartz” Cal. 1270. This was Switzerland’s first quartz chronograph with traditional analog hands, arriving shortly before the Jaeger-LeCoultre Cal. 630 (confusingly called the “Mechaquartz”), though Seiko beat both companies to the punch, introducing their “Mecha-Quartz” Cal. 7A in 1982. Although Blancpain shunned quartz, sister company Frédéric Piguet was actively involved in this area.

The SMH Buys Blancpain

By 1992, Nicolas Hayek saw the success of other companies and decided he needed a high-end watchmaking savior. But SMH had sold Lemania back in 1981, and Nouvelle Lemania (as it was now known) was actively being pursued by Investcorp, owner of Breguet, Chaumet, and Tiffany.

Blancpain’s partner company, Frédéric Piguet, was in need of capital and put itself up for sale in 1991. Biver tried to put together financing with Jean-Marc Jacot, formerly of Ebel, but was distracted by a divorce. Nicolas Hayek made an offer on behalf of SMH, sensing the opportunity in high-end mechanical and quartz movements. Rather than have Blancpain lose their business partner and movement producer, Biver decided that Blancpain should join the offer.

On July 8, 1992, the deal was announced: SMH would acquire both Frédéric Piguet and Blancpain for CHF 60 million.

Biver did not want to work for Hayek, but couldn’t be left on the sidelines of the industry. So three weeks later he called, asking to return. Hayek put him in charge not just of Blancpain but also Omega, which had not enjoyed the success of competing brands. Focusing on Omega, Biver tripled its annual revenue to over CHF 1 billion by the end of the decade, while Blancpain remained true to its high-end niche.

With Blancpain and Frédéric Piguet secure, Biver and SMH invested in the brand’s bona fides. Rather than compete with Omega as a mainstream luxury watch brand, Blancpain focused on high-end watches in precious metals and jewels with complex mechanical movements. SMH gave Blancpain the resources to develop a new ultra-compact automatic movement, and this was launched around 1998 as the new Blancpain Ladybird.

Blancpain celebrated its heritage with the Montre Jubilé. This simple watch featured a gold case and ultra-thin movement. It was introduced in 1993 to commemorate 300 years since the birth of Jehan-Jacques Blancpain. Now that the brand was back inside SMH, it had a credible link back to this history.

Edmond Capt left in 1992 to become Technical Director for Nouvelle Lemania. There, he developed movements for Blancpain rival Breguet, which remained independent. But he returned to Frédéric Piguet in 1994, becoming General Director of the firm. Capt and his staff continued development of their tourbillon, creating a skeletonized version in 1997. An automatic tourbillon and more sports-oriented models followed the next year, including a tourbillon chronograph.

Direct management of Blancpain was turned over that year to Steven Urquhart, formerly of Audemars Piguet, but Biver remained CEO even as his health declined due to Legionnaire’s Disease the following year. By the end of the 1990s, Blancpain was one of the most respected names in mechanical watchmaking.

But Hayek was looking elsewhere by this time. On September 14, 1999, Swatch Group (called SMH until 1998) acquired Breguet and Nouvelle Lemania. This would become the top of the pyramid within the group, with Blancpain pushed aside. Today, both brands (along with Jaquet Droz) are under the personal supervision of Marc Hayek. Frédéric Piguet was renamed “Manufacture Blancpain” in 2010, while Nouvelle Lemania became “Manufacture Breguet”. And Edmond Capt became leader of both “Manufactures”!

Watch this 1991 documentary film to learn more about the watchmaking world at this time: How Charles Vermot Saved the Zénith El Primero – In His Own Words

Biver’s Blancpain Showed the Future

It must have seemed quite foolish to launch a high-end mechanical watch company in 1981, just as Japanese competition was causing havoc in the Swiss watch industry. But Biver saw at Omega that luxury watches, especially complicated ones in precious metal cases, were timeless and held appeal for the next generation. His plan for Blancpain provided a template for the industry, and his work mirrored similar efforts by Günter Blümlein (IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre), Gerd-Rüdiger Lang (Chronoswiss), and the independents that would soon be known as the AHCI. But although Blancpain was an important trendsetter, it would never be a dominant brand. It was simply too soon. Instead, Biver’s script would be followed by Franck Muller, Audemars Piguet, A. Lange & Söhne, Patek Philippe, and today’s haute horology brands. Even Biver himself would follow this path with Hublot, LVMH, and TAG Heuer, but that is a story for another day!

This article accompanies Episode 4 of The Watch Files, a podcast from Europa Star and Grail Watch. Listen to “04 Blancpain, Biver, Piguet, and the Path Forward” and subscribe now!

Postscript: Blancpain’s Heritage

As is the case with most modern brands, the modern Blancpain has marketed its heritage as “the world’s oldest watch company,” referencing Villeret and the Blancpain family, and commemorating the years 1693 and 1725. Biver’s famous slogan is also often repeated: “Since 1735 there has never been a quartz Blancpain. And there never will be.” But how credible is this claim?

While I am not the arbiter of truth in industry marketing, a few facts should be noted:

- Jehan-Jacques Blancpain likely began making watches prior to 1725, with that date merely being the first time he listed “watchmaker” as his profession

- Blancpain’s re-incorporation as Rayville does not interrupt the company’s history, though it does mark a change from family ownership and a transition to become a high-volume producer of movements as well as watches

- The 1961 incorporation of Rayville into the SSIH is less significant than the transition of that holding company into a conglomerate in 1968 – this effectively transformed Omega, Tissot, and Blancpain into brands rather than companies

- Blancpain was finished in the late 1970s, with all production ceased and all materials destroyed, but Rayville continued as a manufacturer of movements for the SSIH brands

- The re-establishment of Blancpain in 1991 marked the creation of a new company entirely, headquartered far from Villeret in Le Brassus, alongside Frédéric Piguet

- Rayville became Omega’s Villeret manufacturing center under ETA, ending any connection to Blancpain, and today is segmented from Blancpain within Swatch Group

- Blancpain’s sister company, Frédéric Piguet, was actively involved in the development of quartz movements, including the revolutionary Meca-Quartz

- The 1992 acquisition of Blancpain and Frédéric Piguet by SMH technically reunited the brand with its historic owner, but there was no continuity in design, manufacturing, or management between the modern brand and the historic Villeret company

The fact that there is a direct line from the Blancpain family in Villeret through Rayville, SSIH, SMH, and Swatch Group gives some credibility to the claims of “1725” heritage, but the interruption of production, destruction of materials, and re-launch far away in Le Brassus raise some red flags. And then there is Biver’s famous pronouncement about quartz: The fact that no quartz watch used the Blancpain brand is more a sad reflection on the failure of the company than a sign of pride. Still, it made for good marketing and Biver was correct in seeing that this would be the bedrock for his new company and for the industry.

Another irony comes from the current connection with Breguet. Lemania was closely related to Rayville and Blancpain in the SSIH years, but history had other plans for these companies. The unrelated external company Frédéric Piguet would become “Manufacture Blancpain” thanks to the efforts of Jean-Claude Biver, giving the modern brand more connection to its establishment in 1858 in Le Brassus. Lemania, which was also sold in 1981, would become “Manufacture Breguet” inside the Swatch Group, being paired with an unrelated external brand, Breguet. In the 1970s, it would have seemed more likely that these pairings would be reversed!

References

- Jean-Claude Biver: Past, Present, Future, Europa Star, 2019

- Lettres du Brassus, Issue 05

Leave a Reply