Chronographs are so popular that cheap fashion watches today often feature bogus subdials with non-functional hands and pushers. But once upon a time, a chronograph was a simple tool seen more as an advanced stopwatch than a true complication. The story of the chronograph, from military to luxury to sports to fashion, mirrors the trends seen in other areas, from cars to clothing.

1910s-1930s: The Tool Watch

The chronograph was never intended to be a watch. Whether you credit Louis Moinet or Nicolas Rieussec with the invention, the earliest timers were intended for use in military, science, and sport. Through the 18th century, these were variously called chronographes (Rieussec’s name) or compteurs (Moinet’s term) or, commonly, chronographe-compteurs!

Later in the 19th century, the term “compteur” came to be used for the totalizing function, whether it counted seconds (as in Moinet’s Compteur de Tierces), minutes, or hours. This term was then generally applied to any sports timer, as compteurs de sport became popular in various racing competitions. Around the turn of the century, the word “chronograph” began to be a differentiator for a timer that included a running clock, while a “compteur” was one without. But even into the 1940s, producers like Excelsior Park still advertised their wrist chronographs as “Chronographe-Compteur” as seen in the illustration at right.

The wristwatch emerged slowly over centuries, mainly as a jewelry accessory for ladies. But the practicality of a wrist-mounted watch appealed to British solders in the late 19th century, and wristwatches for men began appearing in the 1880s. The concept was certainly well accepted by 1889, when a patent for a “montre bracelet simplifée” was granted to Albert Bertholet of Bienne. But chronograph movements were rapidly evolving at the time and were not yet small enough to be worn on the wrist.

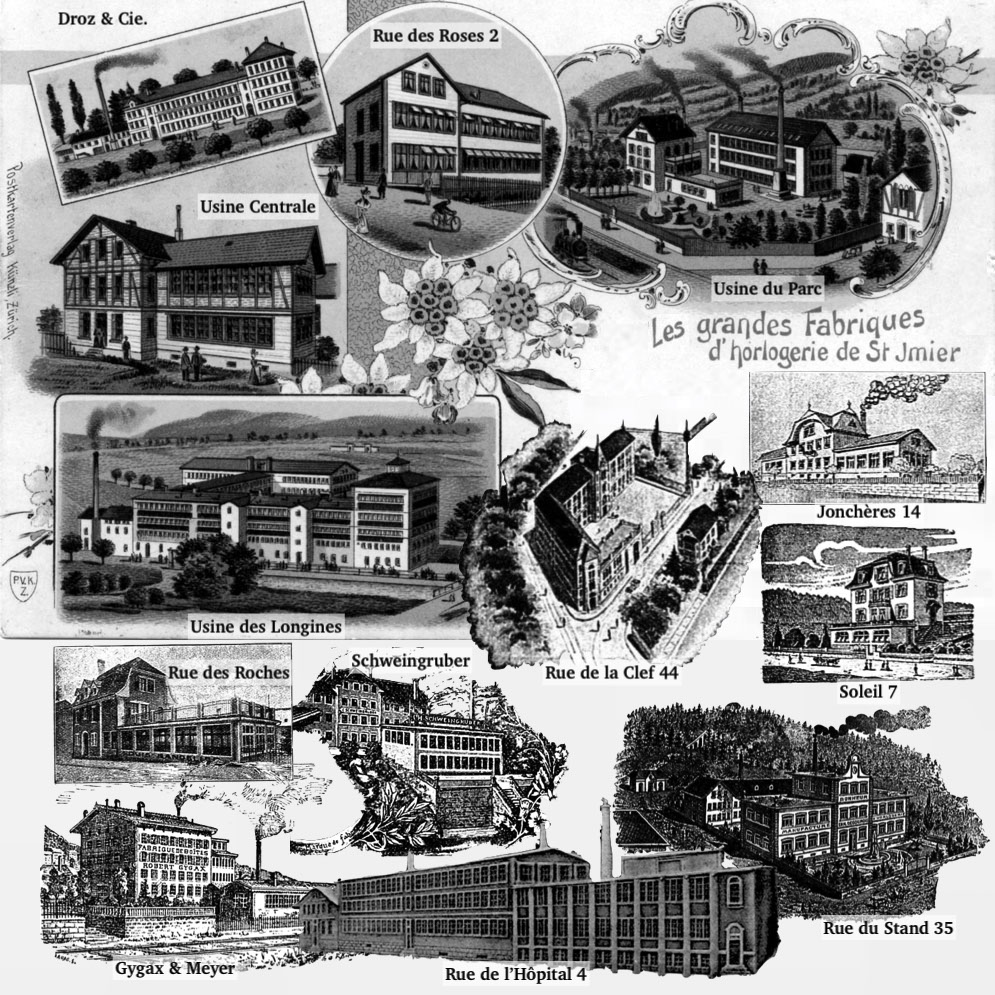

1913 marks the emergence of the “bracelet-chronographe-compteur.” Although many credit Longines or Heuer for the creation of the first chronograph wristwatch, there are a half-dozen such models listed in Indicateur Davoine that year, from watchmakers like Henchoz Fils, Ed. Heuer, Samuel Jeanneret (Colombe), and Nathan Weil (pictured at left). Many at that time surely used the Longines Cal. 13.33Z, which measured just 13 ligne (29.8 mm) diameter, easily the first such movement small enough to be strapped to the wrist. But others used larger movements measuring 14 (Valjoux), 15 (Heuer), 16 (Weil), 17 (Henchoz), or even 19 ligne (Colombe).

By 1916, bracelet chronographs are found from many brands, with numerous movements in production. These include a 16 ligne Martel movement, shown here. This would be the template for chronographs through the 1920s.

Over the next decades, the chronograph wristwatch became an indispensable tool for soldiers, scientists, and engineers. But the timing component often compromised power reserve or accuracy when engaged, which limited the market for these watches. Although complications like date pointers and more complicated calendars were in demand, chronographs were not widely embraced by the general public.

The design of these watches advanced rapidly, from “marriage” models with soldered wire to hold the strap to cases with more-developed lugs. Another key advancement was the development of separate pushers to start, stop, and reset the chronograph function. Breitling was a key innovator here, bringing the independent pusher to market in 1915. The “monopusher in crown” design would last for a few more decades, but the modern dual-pusher chronograph rapidly eclipsed it.

As they separated from pocket watch roots, chronograph movements were simplified. Instantaneous reset levers were scrapped, and the jungle of components found in larger movements were reduced in favor of more economical springs.

Today, these classic chronographs are collectible but not exactly valuable. Many saw years of hard use and little maintenance, but even those in good shape are not as appealing to modern collectors. This likely comes down to their dated styling, which is more reminiscent of a pocket watch than anything found in a modern sales counter. Another factor is likely the disappearance of many brands from the early part of the 20th century, few of which survived the depression and the wars.

1940s-1950s: The Doctor’s Watch

After World War II, the market for the chronograph watch expanded dramatically. The post-war economic boom meant that doctors and scientists could afford a classy and stylish chronograph. And improved technology and production capacity meant the chronograph could become an every-day watch for the first time. Although fine watchmakers like Patek Philippe, Henri Audemars, Charles Golay, and Eugene-Adolph Capt had produced chronographs since the 1860s, these were rare and special pieces. In the 1940s, chronographs became popular for the first time.

Doctors had long used a small seconds hand for pulse timing, but a chronograph could provide timing on demand with a dedicated pulsometer scale. This created demand for stylish chronograph watches in precious metal cases, and companies like Universal and Zenith (powered by Martel), Gallet and Girard-Perregaux (Excelsior Park), Heuer (Valjoux), Breitling (Venus), and Leonidas were happy to oblige.

Perhaps the most important chronograph movement in this period was the Valjoux 72, introduced in 1938 and still considered one of the finest movements ever made. It featured a 12 hour counter, giving a 3-6-9 arrangement that brought balance and class to the upscale chronograph. The date was indicated at the periphery of the dial using a central hand, and day and month were shown in windows below the 12. Other movements featured a date pointer in the 6:00 subdial rather than the hour totalizer. These so-called triple-calendar movements were sometimes augmented with a moon phase indicator inside the 6:00 subdial. This gave a classy look that would become the blueprint for the resurgence of complicated watches in the 1990s.

After the Stern family took over Patek Philippe, they began to produce more complicated watches, including the fabulous World Time Chronograph, Ref. 1415. Calendar chronographs were equally important in the 1950s, notably the Patek Philippe Ref. 1518, but also important models from Girard-Perregaux, Longines, and Rolex.

Today, these dress calendar chronograph watches are very much in demand, and the rare Patek Philippe 1518 can command millions of dollars at auction. Even lesser models from Rolex, Universal, and Girard-Perregaux are rising rapidly in price as collectors see the appeal of this era of triple-calendar chronograph watches. Although relatively small by modern standards, they were considered over-sized at the time and many struggled to find buyers. Things have certainly changed!

1960s-1980s: The Sports Watch

Greater disposable income in the post-war period allowed more people to take part in sports, with motor racing and diving becoming popular. These activities captured the imagination of younger consumers, hungry for a break from decades of war and economic crisis. These activities require accurate timing, and Breitling, Enicar, Heuer, Omega, Nivada, Rolex, and Universal began offering eye-catching sports chronographs.

By 1963, sport chronographs were a serious market trend, with particular appeal to teenagers. As discussed by PR guru Georges Caspari in a 1963 Europa Star article, chronographs had an undeniable energy and appeal to the “teenage” market. These brands leveraged this newfound attention to create an entirely different product, with racing-inspired design elements and evocative model names like Monte Carlo, Autavia, Carrera, and (eventually) Daytona.

Image: Europa Star 24, 1963

Chronograph watches had always been marketed exclusively towards men, since they tended to be larger and more utilitarian than so-called “ladies watches.” But 1968 saw the use of colorful new materials like fiberglass, resulting in less-serious models that appealed to young women as well. Throughout the 1970s, chronographs survived the onslaught of electronic and quartz watches and even expanded their market with affordable and unisex offerings. Low-priced cam-actuated movements like the Valjoux 7750 and Lemania 5100 bridged the gap until mechanical movements returned in the 1980s.

Sports chronographs from the 1960s are very much in demand today, and frequent reissues and homages only make them more desirable. The funky styling of many of these watches makes them just as eye-catching today as in 1969, and many models are linked to timeless icons like Paul Newman, Steve McQueen, Buzz Aldrin, Jean-Claude Killy, and Mario Andretti. To say that sports chronographs are in demand is a serious understatement!

1990s-Today: The Complicated Watch

As we have discussed many times before, the collapse of the Swiss watch industry was caused by the end of post-war economic stability (Breton Woods and Nixon), the rise of electronics in Japan and the United States, and mass production of commodity watches. Visionaries like Günter Blümlein, Jean-Claude Biver, Gerd-Rüdiger Lang, and Franck Muller saw that complicated watches could be a path forward for Swiss watchmaking. Starting in 1983, they produced complicated offerings with features not seen in any quartz watch, and consumers responded by purchasing a new generation of high-priced Swiss watches.

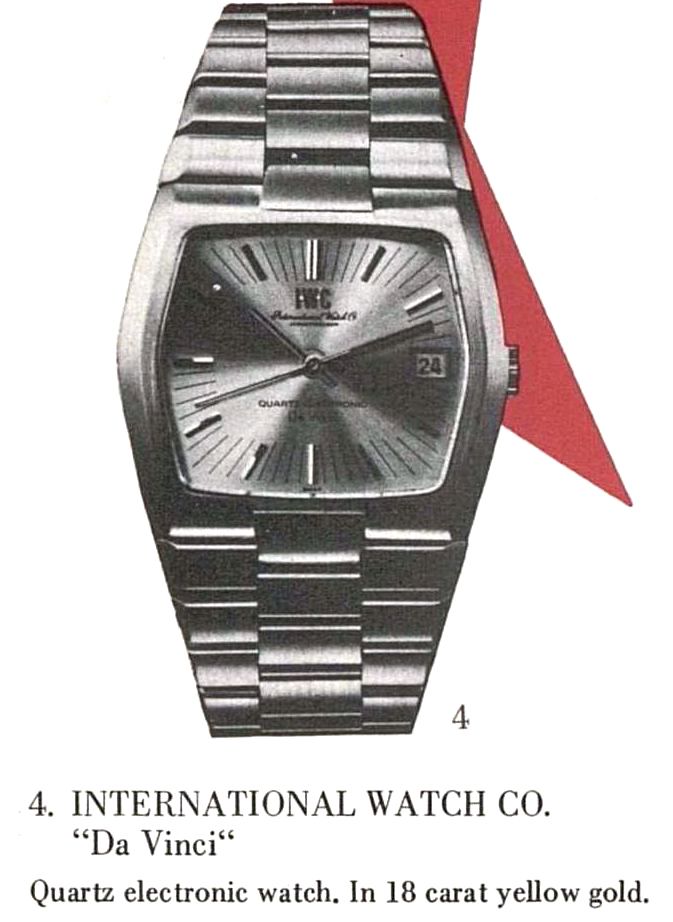

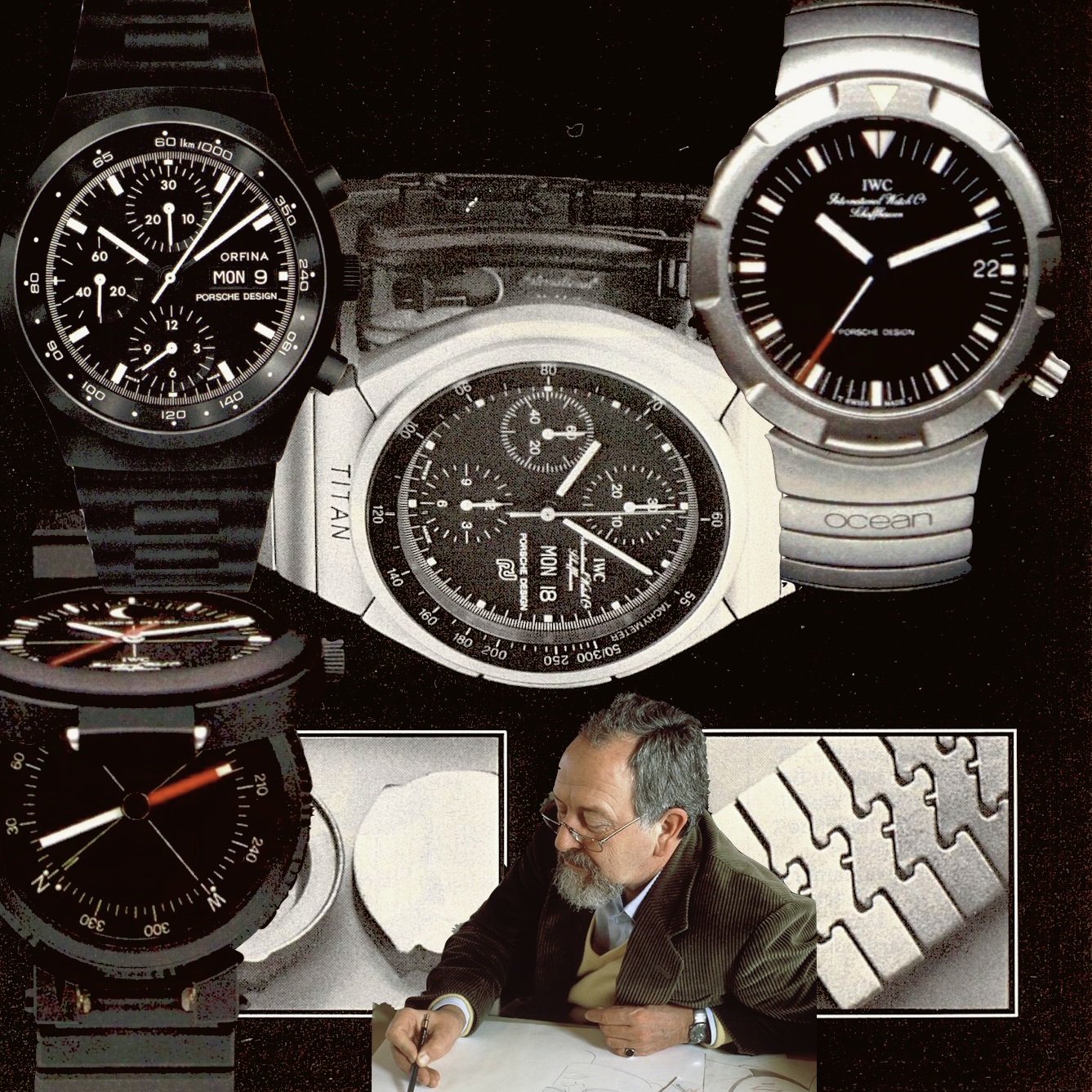

This trend was exemplified by Kurt Klaus’ remarkable IWC Da Vinci, which added a perpetual calendar and moon phase display to the humble Valjoux 7750 automatic chronograph movement. The result was a four-subdial watch that resembled classic grand complications from Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet, while also suggesting the classic Valjoux 88 watches of the 1950s. With nine hands, no quartz watch came close to the Da Vinci, and IWC emphasized the technological ingenuity of the watch in their advertising.

Ironically, the first quartz analog chronographs appeared on the market that same year! Seiko was first with the 7a, followed closely by Heuer’s 6-hand quartz. Equally surprising is that it was Frédéric Piguet (“never-quartz” Blancpain’s movement provider) and Jaeger-LeCoultre (Blümlein’s poster child for mechanical movements) who brought high-end quartz chronograph movements to the market four years later!

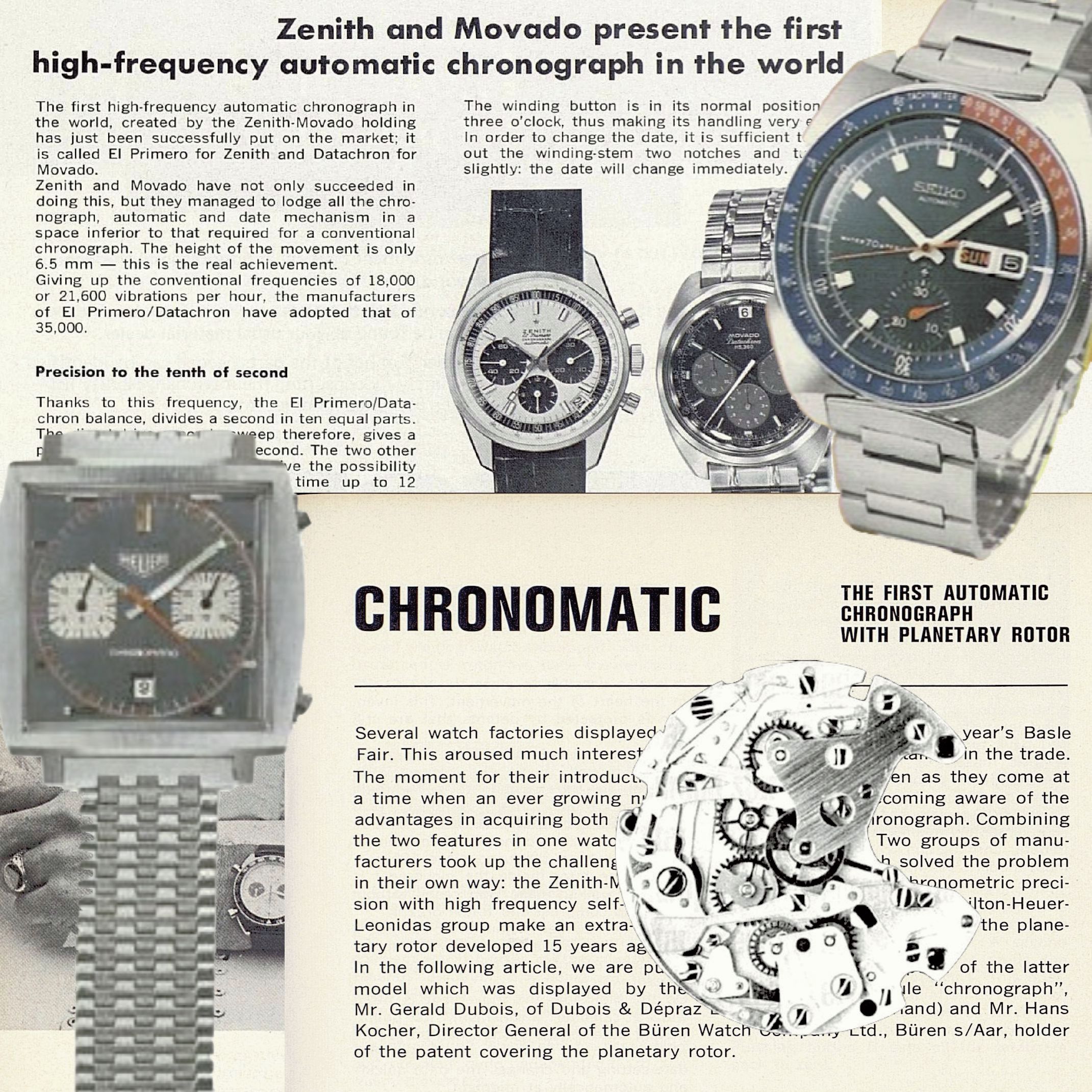

Demand for mechanical chronographs rose rapidly into the 1990s, but few such movements were available. Zenith brought the El Primero back into production, enabling Ebel, Rolex, and Zenith itself to re-enter the market. And ETA brought the Valjoux 7750 back as well, with the humble movement becoming the engine of choice for complicated automatic watches that followed IWC’s Da Vinci. At the high end, Frédéric Piguet’s new Cal. 1185 was found in important models from Audemars Piguet, Blancpain, Breguet, and Franck Muller.

Independent watchmakers rose in the 1990s as well, joining Vincent Calabrese and Svend Andersen at the AHCI. Although some independents produced signature chronograph watches, notably Daniel Roth, Franck Muller, and Andersen himself, most chose to express their watchmaking skills with more exotic complications. Still, the mainstream high-end was a world of chronographs. Eventually, Audemars Piguet, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Rolex, and Omega would create in-house chronograph movements of their own, using the complication as a sign of their watchmaking skills.

The Grail Watch Perspective: The Chronograph is a Complication for Everyone

Today, the chronograph is firmly established as the most accessible complication found in upscale watches, but it has been a long and winding road to get here. What was once a utilitarian tool for soldiers became an upscale choice for doctors, then an iconoclast choice for young people, and now a sign of fine watchmaking. Even today, with a dozen different chronograph movements in production, this seemingly-simple complication has proven a challenge to master. Companies from Seiko to Rolex have been forced to redesign and improve their designs, and watchmakers know the challenge of making a smooth and reliable chronograph. Yet the signature subdial look is ubiquitous in fashion watches, showing the public appetite for chronographs.

Thanks for the interesting information. It surely beats all of the political noise.

Definitely no politics here!